Appendix BInterview Questionnaire

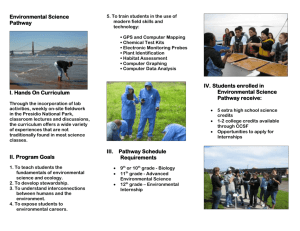

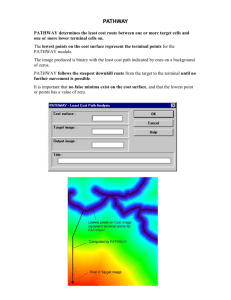

advertisement