AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT INVESTIGATIONS

advertisement

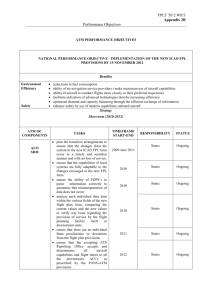

AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION:1 Historical Background (a) (b) (c) (d) (e) (f) (g) In September 1908 Orville Wright flew with Lieutenant Thomas Selfridge to demonstrate aircraft flying. Aircraft crashed resultantly Orville Wright got injured severely and Lieutenant Thomas Selfridge died. First investigation was convened to investigate the accident. The procedures for air accident investigations were first laid down in 1928 by the US National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics . In 1944 the Chicago Convention drafted a set of procedures and processes to govern the burgeoning international civil aviation industry. These standards and recommended practices were developed by the Accident Investigation Division between February 1946 and February 1947, and were later designated as Annex 13 of the convention. The primary focus of Annex 13 differed from that of the US National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics in 1928: it was no longer to find fault and apportion blame for an aircraft accident, but to provide a mechanism by which participants in the industry - pilots, aircraft manufacturers and regulatory agencies – could learn from their mistakes. Standards and Recommended Practices for Aircraft Accident Inquiries were first adopted by the Council on 11 April 1951 pursuant to Article 37 of the Convention on International Civil Aviation (Chicago, 1944) and were designated as Annex 13 to the Convention. Article 37 imposes an obligation on the State in which the aircraft accident occurs to institute an inquiry in certain circumstances and, as far as its laws permit, to conduct the inquiry in accordance with ICAO procedure. Accident. An occurrence associated with the operation of an aircraft which takes place between the time any person boards the aircraft with the intention of flight until such time as all such persons have disembarked, in which: a) a person is fatally or seriously injured as a result of: — being in the aircraft, or — direct contact with any part of the aircraft, including parts which have become detached from the aircraft, or — direct exposure to jet blast, except when the injuries are from natural causes, self- inflicted or inflicted by other persons, or when the injuries are to stowaways hiding outside the areas normally available to the passengers and crew; or b) the aircraft sustains damage or structural failure which: — adversely affects the structural strength, performance or flight characteristics of the aircraft, and — would normally require major repair or replacement of the affected component, except for engine failure or damage, when the damage is limited to the engine, its cowlings or accessories; or for damage limited to propellers, wing tips, antennas, tires, brakes, fairings, small dents or puncture holes in the aircraft skin; or c) the aircraft is missing or is completely inaccessible. Accidents and Fatalities by Phase of Flight Causes of Fatal Accidents by Decade (percentage) Causes 1970 1980 1990 2000 Pilot Error 24 26 30 39 Pilot Error (weather related) 14 18 19 19 Pilot Error (mechanical related) 5 2 5 5 Total Pilot Error 43 46 54 63 Other Human Error 9 6 9 5 Weather 14 14 10 8 Mechanical 20 20 18 24 Sabotage 13 13 11 9 Other Causes 1 1 1 0 • 1. Airbus 340 The A340 has approximately the same number of flying hours as the 777 and remains accident-free, making it number one in safety. Number in service 355 • 2. Boeing 777 At one accident per eighteen-million hours of flying, the Triple-Seven is number two in safety. And, in that one accident, everyone survived. Number in service: 792vice: • 3. Boeing 747 When Boeing first considered building a plane that would carry 500 passengers, the board of directors was skeptical. People had gotten used to hearing of an air crash with one-hundred or so fatalities. So, the thinking was, if Boeing invested all its resources in a 500-passenger plane a crash could so traumatize the public that passengers would refuse to fly it. "No problem," the engineers said, "We are going to build an uncrashable airplane." And they almost did. The record shows about seventeen-million hours per accident, but two of those had nothing to do with the quality of the plane: the collision of two 747s on the runway in the Canary Islands. Due to misunderstanding communications from the tower, a KLM 747 took off when not cleared for takeoff, striking a Pan Am 747, destroying both planes. Number in service: 838 • 4. Airbus 320 In a virtual tie with the Boeing 757, the Airbus 320 has fourteen-million hours per accident. It was first built in 1988. Number in service: 3,604 1.CANYON | TWA Flight 2 and United Airlines Flight 718 Upgrade: Improvements of air traffic control system; creation of FAA The TWA Super Constellation and the United DC-7 had taken off from Los Angeles only 3 minutes apart , both headed east. Ninety minutes later, out of contact with ground controllers and flying under see-and-avoid visual flight rules, the two aircraft were apparently maneuvering separately to give their passengers views of the Grand Canyon when the DC-7's left wing and propellers ripped into the Connie's tail. Both aircraft crashed into the canyon, killing all 128 people aboard both planes. The accident spurred a $250 million upgrade of the air traffic control (ATC) system-serious money in those days. (It worked: There hasn't been a collision between two airliners in the United States in 47 years.) The crash also triggered the creation in 1958 of the Federal Aviation Agency (now Administration) to oversee air safety. • 2.DALLAS/FORT WORTH | Delta Air Lines Flight 191 • Upgrade: Downdraft detection As Delta Flight 191, a Lockheed L-1011, approached for landing at Dallas/Fort Worth airport, a thunderstorm lurked near the runway. Lightning flashed around the plane at 800 ft., and the jetliner encountered a microburst wind shear--a strong downdraft and abrupt shift in the wind that caused the plane to lose 54 knots of airspeed in a few seconds. Sinking rapidly, the L-1011 hit the ground about a mile short of the runway and bounced across a highway, crushing a vehicle and killing the driver. The plane then veered left and crashed into two huge airport water tanks. On board, 134 of 163 people were killed. The crash triggered a seven-year NASA/FAA research effort, which led directly to the on-board forward-looking radar windshear detectors that became standard equipment on airliners in the mid-1990s. Only one wind-shear-related accident has occurred since. 3.United Airlines Flight 173 Upgrade: Cockpit teamwork United Flight 173, a DC-8 approaching Portland, Ore., with 181 passengers, circled near the airport for an hour as the crew tried in vain to sort out a landing gear problem. Although gently warned of the rapidly diminishing fuel supply by the flight engineer on board, the captain--later described by one investigator as "an arrogant Pilot."--waited too long to begin his final approach. The DC-8 ran out of fuel and crashed in a suburb, killing 10. In response, United revamped its cockpit training procedures around the then-new concept of Cockpit Resource Management (CRM). Abandoning the traditional "the captain is god" airline hierarchy, CRM emphasized teamwork and communication among the crew, and has since become the industry standard. "It's really paid off," says United captain Al Haynes, who in 1989 remarkably managed to crash-land a crippled DC-10 at Sioux City, Iowa, by varying engine thrust. "Without [CRM training], it's a cinch we wouldn't have made it." 4.CINCINNATI | Air Canada Flight 797 Upgrade: Lav smoke sensors The first signs of trouble on Air Canada 797, a DC-9 flying at 33,000 ft. en route from Dallas to Toronto, were the wisps of smoke wafting out of the rear lavatory. Soon, thick black smoke started to fill the cabin, and the plane began an emergency descent. Barely able to see the instrument panel because of the smoke, the pilot landed the plane at Cincinnati. But shortly after the doors and emergency exits were opened, the cabin erupted in a flash fire before everyone could get out. Of the 46 people aboard, 23 died. The FAA subsequently mandated that aircraft lavatories be equipped with smoke detectors and automatic fire extinguishers. Within five years, all jetliners were retrofitted with fire-blocking layers on seat cushions and floor lighting to lead passengers to exits in dense smoke. Planes built after 1988 have more flame-resistant interior materials. 5. ABQ-202, mishap aircraft A-321, AP-BJB, on 28 July 2010, operated by Airblue was scheduled to fly a domestic flight sector Karachi - Islamabad. The aircraft had 152 persons on board, including six crew members. The Captain of aircraft was Captain Pervez Iqbal Chaudhary. Mishap aircraft took-off from Karachi at 0241 UTC (0741 PST) for Islamabad. At time 0441:08, while executing a circling approach for RWY-12 at Islamabad, it flew into Margalla Hills, and crashed at a distance of 9.6 NM, on a radial 334 from Islamabad VOR. The aircraft was completely destroyed and all souls on board the aircraft, sustained fatal injuries. May Allah bless their souls. Incident. An occurrence, other than an accident, associated with the operation of an aircraft which affects or could affect the safety of operation. Serious incident. An incident involving circumstances indicating that an accident nearly occurred. Note 1.— The difference between an accident and a serious incident lies only in the result. List Of Serious Incidents a. ,Near collisions requiring an avoidance manoeuvre to avoid a collision or an unsafe situation or when an avoidance action would have been appropriate. b. Controlled flight into terrain only marginally avoided. Aborted take-offs on a closed or engaged runway. c. Take-offs from a closed or engaged runway with marginal separation from obstacle(s). Landings or attempted landings on a closed or engaged runway. d. Gross failures to achieve predicted performance during take-off or initial climb. e. Fires and smoke in the passenger compartment, in cargo compartments or engine fires, even though such fires were extinguished by the use of extinguishing agents. f. Events requiring the emergency use of oxygen by the flight crew . g. Aircraft structural failures or engine disintegrations not classified as an accident. h. Multiple malfunctions of one or more aircraft systems seriously affecting the operation of the aircraft. j. Flight crew incapacitation in flight. K .Fuel quantity requiring the declaration of an emergency by the pilot. l. Take-off or landing incidents. Incidents such as under- shooting, overrunning or running off the side of runways. m. System failures, weather phenomena, operations outside the approved flight envelope or other occurrences which could have caused difficulties controlling the aircraft. n. Failures of more than one system in a redundancy system mandatory for flight guidance and navigation. Aircraft Incidents Date Incident Details August 18, 2003 Both of an Air Canada Airbus A340-300 airplane's center landing gear tires (No.s 9 and 10) shredded during the takeoff roll, damaging the door retraction arms and multiple fuselage skin panels. The flight crew could not retract the landing gear and elected to return to Hawai and performed an uneventful overweight landing. There were no injuries. March 5, 2001 An American Trans-Air L1011 was climbing from Hawai going through 9,000 feet, when the No. 1 engine experienced an uncontained failure in plane of low pressure turbine. Fragments penetrated the left main wheel area and disabled the "C" hydraulic system. The plane returned to Hawai without further incident. There were no injuries. January 5, 2001 An Evergreen International Airlines Boeing 747-200F experienced smoke in the cockpit enroute to Hawai from Pago Pago. No injuries December 29, 2000 A Delta Airlines L-1011 Flight 219 experienced an electrical fire forward of the flight engineer's station while en route from SFO to Hawai. No injuries. Definitions • State of Design. The State having jurisdiction over the organization responsible for the type design. • State of Manufacture. The State having jurisdiction over the organization responsible for the final assembly of the aircraft. • State of Occurrence. The State in the territory of which an accident or incident occurs. • State of the Operator. The State in which the operator’s principal place of business is located or, if there is no such place of business, the operator’s permanent residence. • State of Registry. The State on whose register the aircraft is entered. • Note.— In the case of the registration of aircraft of an international operating agency on other than a national basis, the States constituting the agency are jointly and severally bound to assume the obligations which, under the Chicago Convention, attach to a State of Registry.