Chapter 10

Capital

Budgeting

Techniques

Copyright © 2012 Pearson Prentice Hall.

All rights reserved.

Overview of Capital

Budgeting

Capital budgeting is the process of evaluating

and selecting long-term investments that are

consistent with the firm’s goal of maximizing

owner wealth.

A capital expenditure is an outlay of funds by the

firm that is expected to produce benefits over a

period of time greater than 1 year.

An operating expenditure is an outlay of funds

by the firm resulting in benefits received within 1

year.

10-2

What is capital budgeting?

Analysis of potential additions to fixed assets.

Long-term decisions; involve large

expenditures.

Very important to firm’s future.

Categories of Capital Budgeting:

Replacements needed to continue current

operations. For damaged assets.

Replacement for cost reduction due to obsolete

assets.

Expansion of existing products or markets.

Expansion into new products and markets.

10-3

What is the difference between

independent and mutually exclusive

projects?

Independent projects – if the cash flows

of one are unaffected by the acceptance of

the other.

Mutually exclusive projects – if the

cash flows of one are adversely impacted

by the acceptance of the other.

10-4

What is the difference between normal

and nonnormal cash flow streams?

Normal cash flow stream – Cost (negative

CF) followed by a series of positive cash

inflows. One change of signs.

Nonnormal cash flow stream – Two or

more changes of signs. Most common:

Cost (negative CF), then string of positive

CFs, then cost to close project.

10-5

Criteria to evaluate Capital

Budgeting Projects

Five methods are used to evaluate projects:

(1) Payback

(2) Discounted payback

(3) Net Present Value (NPV)

(4) Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

(5) Modified Internal Rate of Return (MIRR)

10-6

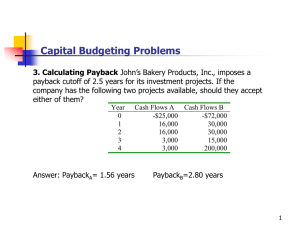

What is the payback

period?

The number of years required to recover a

project’s cost by its net revenue, or “How

long does it take to get our money back?”

Calculated by adding project’s cash inflows to

its cost until the cumulative cash flow for the

project turns positive.

10-7

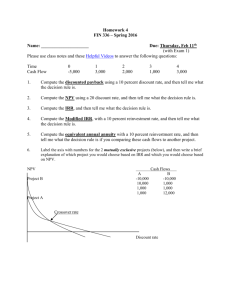

Calculating payback (when

uneven CF)

Project L

CFt

Cumulative

PaybackL

Project S

CFt

Cumulative

PaybackS

0

-100

-100

== 2

2

2.4

3

10

-90

60

-30

100

0

80

30 / 80

+

0

1.6

1

-100

-100

== 1

1

70

-30

+

= 2.375 years

2

100 50

0 20

30 / 50

50

3

20

40

= 1.6 years

10-8

Calculating payback (When

the cash flows are equal)

Project A

CFt

0

1

2

2.2

3

-100

45

45

100

45

Pay Back Period= $100/45

= 2.22 years

10-9

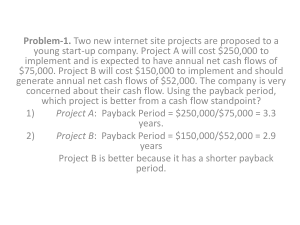

Payback Period Decision criteria:

The payback method is the amount of time required

for a firm to recover its initial investment in a project,

as calculated from cash inflows.

Decision criteria:

The length of the maximum acceptable payback

period is determined by management.

If the payback period is less than the maximum

acceptable payback period, accept the project.

If the payback period is greater than the

maximum acceptable payback period, reject the

project.

10-10

Strengths and weaknesses of

payback

Strengths

Provides an indication of a project’s risk

and liquidity.

Easy to calculate and understand.

Weaknesses

Ignores the time value of money.

Ignores CFs occurring after the payback

period.

10-11

Discounted payback period

Uses discounted cash flows rather than raw CFs.

The length of time required for an investment’s cash

flows, discounted at the investment’s cost of capital,

to cover its cost.

0

10%

CFt

PV of CFt

-100

-100

Cumulative

-100

Disc PaybackL ==

2

10

60

49.59

80

60.11

-41.32

18.79

10/(1+.10)^1=9.09

-90.91

2

+

2.7 3

1

41.32 / 60.11

= 2.7 years

10-12

Net Present Value (NPV)

Net present value (NPV) is a sophisticated capital

budgeting technique; found by subtracting a project’s

initial investment from the present value of its cash

inflows discounted at a rate equal to the firm’s cost

of capital.

NPV = Present value of cash inflows – Initial

investment

10-13

Net Present Value (NPV)

(cont.)

Decision criteria:

If the NPV is greater than $0, accept the

project.

If the NPV is less than $0, reject the project.

If the NPV is greater than $0, the firm will earn a

return greater than its cost of capital. Such action

should increase the market value of the firm, and

therefore the wealth of its owners by an amount

equal to the NPV.

10-14

Figure 10.2 Calculation of NPVs for Bennett

Company’s Capital Expenditure Alternatives

10-15

Project Decision based on NPV

NPV

= PV of inflows – Cost

= Net gain in wealth

If projects are independent, accept if the project

NPV > 0.

If projects are mutually exclusive, accept projects

with the highest positive NPV, those that add the

most value.

For example, accept Project A, if mutually exclusive

(if, NPVA > NPVB)

If no project has a positive NPV, reject them all.

10-16

Internal Rate of Return

(IRR)

A project’s IRR is the discount rate that

forces the PV of cash inflows to equal the

cost (initial outlay).

This is equivalent to forcing the NPV to equal

zero .

The IRR is an estimate of the project’s rate of

return, and it is comparable to the YTM on a

bond.

10-17

Rationale for the IRR method

If IRR > WACC, the project’s rate of

return is greater than its costs.

There is some return left over to

boost stockholders’ returns.

10-18

Project decision based on IRR

Independent projects: If IRR exceeds

the project’s WACC (k) accept the

project and vice versa.

Mutually exclusive projects: Accept the

project with the highest IRR, provided

the IRR is greater than WACC. Reject all

projects if the best IRR does not exceed

WACC.

10-19

IRR Acceptance Criteria

If IRR > k, accept project.

If IRR < k, reject project.

If projects are independent, accept

both projects, as both IRR > k

If projects are mutually exclusive,

accept A, because IRRA > IRRB.

10-20

NPV vs IRR

IRR is logically appealing since it is useful

to know rates of return on proposed

investments.

However when NPV and IRR give

conflicting conclusions then it is better to

decide based on NPV.

◦

◦

NPV assumes cash flows are reinvested at

WACC which is possible in reality.

IRR assumes cash flows are reinvested at IRR

which is flawed.

10-21