META el 12 de junio 2013

advertisement

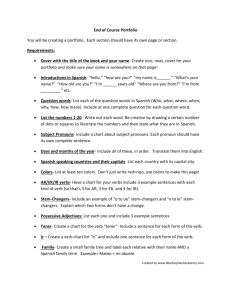

Español V lesson el 12 de junio 2013 el examen final Capítulo 1 - Capítulo 5 Make up tests and Adelante Realidades 3 Capítulo 5 Oral tests completed Always See homework at the end of the website lessons! de META el 12 de junio 2013 el 12 de junio 2013 Capítulo 5 examen make up tests complete ESPECIAL: ORAL FINALS CONTINUE……. Capítulo 5 Cultura REPASO de los VERBOS Presente Presente indicativo Presente progresivo El subjuntivo Presente perfecto Presente perfecto del subjuntivo Pluscuamperfecto Direct Object Pronouns Indirect Object Pronouns The Position law of object pronouns Al examinar las preguntas acerca de las actividades y de cultura para el examen final. El Arte Repasen Uds. Las lecciones sobre el arte España, México, Cuba, Puerto Rico….. La Práctica de usar el subjuntivo en frases para expresar la esperanza o la duda de cualque situación……. Al usar el pretérito, el imperfecto, el pluscualperfecto ………. Repasen Uds. Todos… La Preparación para el presente perfecto del subjuntivo - Y por fin, La historia del arte de España Períodos de movimientos del arte en repaso….. Música de lo Medieval , Renacimiento, Baroco…hasta el siglo XX LA GRAMÁTICA AQUÍ El Presente Perfecto del Subjuntivo Realidades 3 Página 227 The present perfect subjunctive is a compound verb tense that describes actions that may have happened. For example, you may have studied Spanish if your high school had offered it. That may have verb phrase? That’s the present perfect subjunctive. Haya hayas haya hayamos hayáis hayan Me alegro de que hayas trabajado de voluntario. Estoy orgullosa de que Julián haya trabajado en el centro de rehablitación. Ojalá que ellos hayan juntado mucho dinero. Siento que no hayan participado en la campañía. Repaso- present perfect tense I have studied. Yo he estudiado. HABER Present tense he has ha hemos habéis han Imperfect tense of HABER Había habías había Habíamos Habíais Habían He estudiado. I have studied Había estudiado. I had studied. You form the present perfect subjunctive by beginning with the verb haber (to have) conjugated in the appropriate tense (in this case, present subjunctive). Then you simply add the past participle of the main verb. The following table shows haber conjugated in the present subjunctive. The Present Subjunctive Tense of Haber Conjugation Translation yo haya I may have tú hayas You (informal) may have él/ella/ello/uno haya He/she/one may have usted haya You (formal) may have nosotros hayamos We may have vosotros hayaís You all (informal) may have ellos/ellas hayan They may have ustedes hayan You all (formal) may have the first-person (yo), and the thirdperson (él, ella, Ud.) singular forms of the verb haber are the same in the present subjunctive. Here are some example sentences using the present perfect subjunctive: La madre duda que los niños hayan limpiado sus cuartos. The mother doubts that the children have cleaned their rooms. Yo espero que ellos hayan despegado en el vuelo correcto. I hope that they have taken the right flight. demonstratives of two types Demonstrative Adjectives and Demonstrative Pronouns. The first step in clearly understanding these two topics is to review the differences between "adjectives" and "pronouns." adjective describes a noun pronoun takes the place of a noun In the following sentences, the words in bold all function as adjectives, since they all describe the noun "book." Give me the red book. Give me the big book. Give me that book. Give me this book. Notice that adjectives answer the question "Which?" in relation to the nouns that they modify. (Which book? The red book. The big book. That book. This book.) In the following sentences, the words in bold all function as pronouns, since they all take the place of a noun. Maria is next; give her the ball. Juan is here; say hello to him. That pencil is yours; this is mine. This book is mine; that is yours. Notice that pronouns replace a noun. ("her" replaces "Maria" - "him" replaces "Juan" "this" replaces "pencil" - "that" replaces "book") As you have just seen, the words "this" and "that" can function as both adjectives and pronouns. This book is mine. (adjective) This (one) is mine. (pronoun) That book is yours.(adjective) That (one) is yours. (pronoun) The same is true in Spanish. Juan reads this book. (adjective) Juan lee este libro. Juan reads this. (pronoun) Juan lee este. That statue is Greek. Esa estatua es griega. That (one) is American. Esa es americana. Spanish has three words where English only has two. In English, we say "this" or "that" depending upon whether the object is close to us or not. In Spanish, we also say "this" and "that," but there is another, separate word used to mean "that one over there." This form is used when the object is more than just a short distance away, for example, on the other side of the room. Here are the three forms for "this" "that" and "that one over there." este this ese that aquel that one over there In Spanish, adjectives have four forms: masculine singular, masculine plural, feminine singular, feminine plural. For example the adjective "short" has four forms in Spanish: bajo, bajos, baja, bajas. el chico bajo los chicos bajos la chica baja las chicas bajas The demonstrative adjectives also have four forms: este libro (this book) estos libros (these books) esta pluma (this pen) estas plumas (these pens) ese libro (that book) esos libros (those books) esa pluma (that pen) esas plumas (those pens) aquel libro (that book over there) aquellos libros (those books over there) aquella pluma (that pen over there) aquellas plumas (those pens over there) Here are the corresponding demonstrative pronouns: este (this one - masculine) estos (these ones - masculine) esta (this one - feminine) estas (these ones - feminine) ese (that one - masculine) esos (those ones - masculine) esa (that one - feminine) esas (those ones - feminine) aquel (that one over there - masc.) aquellos (those ones over there - masc.) aquella (that one over there - fem.) aquellas (those ones over there - fem.) Each demonstrative pronoun also has a neuter form. They do not change for number or gender, and they are used to refer to abstract ideas, or to an unknown object. esto (this matter, this thing) eso (that matter, that thing) aquello (that matter/thing over there) Los Adjetivos ylos pronombres demostrativos Present perfect The present perfect is a grammatical combination of the present tense and the perfect aspect, used to express a past event that has present consequences. The term is used particularly in the context of English grammar, where it refers to forms such as "I have eaten" and "Sue has left". These forms are present because they use the present tense of the auxiliary verb have, and perfect because they use that auxiliary in combination with the past participle of the main verb. (Other perfect constructions also exist, such as the past perfect: "I had eaten.") They may also have different ranges of usage – for example, in both of the languages just mentioned, the forms in question serve as a general past tense, at least for completed actions. In English, completed actions in many contexts are referred to using the simple past verb form rather than the present perfect. English also has a present perfect progressive (or present perfect continuous) form, which combines present tense with both perfect aspect and progressive (continuous) aspect: "I have been eating". In this case the action is not necessarily complete; the same is true of certain uses of the basic present perfect when the verb expresses a state or a habitual action: "I have lived here for five years." In modern English, the auxiliary verb for forming the present perfect is always to have. A typical present perfect clause thus consists of the subject, the auxiliary have/has, and the past participle (third form) of the main verb. Examples: I have eaten some food. You have gone to school. He has already arrived in Catalonia. He has had child after child... (The Mask of Anarchy, Percy Shelley) Lovely tales that we have heard or read... (Endymion (poem), John Keats) Early Modern English used both to have and to be as perfect auxiliaries. Examples of the second can be found in older texts: Madam, the Lady Valeria is come to visit you. (The Tragedy of Coriolanus, Shakespeare) Vext the dim sea: I am become a name... (Ulysses, Tennyson) Pillars are fallen at thy feet... (Marius amid the Ruins of Carthage, Lydia Maria Child) I am come in sorrow. (Lord Jim, Conrad) In many other European languages, the equivalent of to have (e.g. German haben, French avoir) is used to form the present perfect (or their equivalent of the present perfect) for most or all verbs. However, the equivalent of to be (e.g. German sein, French être) serves as the auxiliary for other verbs in some languages, such as German, Dutch, French, and Italian (but not Spanish or Portuguese). Generally, the verbs that take to be as auxiliary are intransitive verbs denoting motion or change of state (e.g. to arrive, to go, to fall). For more details, see Perfect constructions with auxiliaries. In particular languages In many European languages, including standard German, French and Italian, the present perfect verb form usually does not convey perfect aspect, but rather perfective aspect. In these languages, it has usurped the role of the simple past (i.e. preterite) in spoken language, and the simple past is now really only used in formal written language and literature in standard English, Spanish, and Portuguese, by contrast, the present perfect and simple past are both common, and have distinct uses. English The present perfect in English is used chiefly for completed past actions or events, when no particular past time frame is specified or implied for them (it is understood that it is the present result of the events that is significant, rather than their actual occurrence). When a past time frame (a point of time in the past, or period of time which ended in the past) is specified for the event, explicitly or implicitly, the simple past is used rather than the present perfect. It can also be used for ongoing or habitual situations continuing up to the present time (and not necessarily completed), particularly in describing for how long or since when something has been the case. In this case the present perfect progressive form is often used, if a continuing action is being described. For examples, see Uses of English verb forms: Present perfect, as well as the sections of that article relating to the simple past, present perfect progressive, and other perfect forms. Spanish The Spanish present perfect form conveys a true perfect aspect. Standard Spanish is like English in that haber is always the auxiliary regardless of the reflexive voice and regardless of the verb in question. For example I have eaten (Yo he comido) They have gone (Ellos han ido) He has played (Él ha jugado) Spanish differs from French, German, and English in that its have cognate, haber, serves only as auxiliary in the modern language; it never indicates possession, which is handled instead by the verb tener. In some forms of Spanish, such as the Rio Platense Spanish spoken in Argentina, the present perfect is rarely used: the simple past replaces it. Pluperfect Tense Pluscuamperfecto - Spanish Pluperfect The Spanish pluperfect (aka past perfect) is used to indicate an action in the past that occurred before another action in the past. The latter can be either mentioned in the same sentence or implied. Ya había salido I had already left (cuando tú (when you called). llamaste). No habían comido (antes de hacer su tarea). They hadn't eaten (before doing their homework). I went to the store Fui al mercado por this morning; I had la mañana; ya already gone to the había ido al banco. bank. Conjugating the Spanish Pluperfect The pluperfect is a compound verb formed with the imperfect of the auxiliary verb haber + the past participle of the main verb. HABLAR había yo hablado tú habías hablado él había ella hablado Ud. habíamos nosotros hablado habíais vosotros hablado ellos ellas Uds. habían hablado SALIR yo había salido nosotros tú habías salido vosotros habíais salido él había ella salido Ud. ellos ellas Uds. habíamos salido habían salido Compound Tenses Spanish Verb Lessons La historía del Arte Movements in arte history de …España 14th Century Italian Renaissance Early Italian Renaissance - 15th Century Early Northern Renaissance - 15th Century High Italian Renaissance - 16th Century Northern Renaissance 16th Century Mannerism (21) Baroque and Rococo Italian Baroque (38) Spanish Baroque (14) Flemish Baroque (11) Dutch Baroque (19) French Baroque (11) Rococo (2) The Natural (15) Neoclassical ) French Neoclassical (20) American Neoclassical (1) Romantic (34) Landscape Painting (7) Modernism (1850 - 1900) (109) Realism (33) Photography (4) Academic Painting (7) Impressionism (48) Post Impressionism (70) Art Nouveau (12) 20th Century Expressionism (362) Cubism (28) Synthetic Cubism (5) Analytic Cubism (8) Futurism (10) Dada (113) Precisionism (62) American Scene (15) Surrealism (117) Suprematism and Constructivism (36) Abstract Expressionism (5) Post-Painterly Abstraction (1) Performance Art (2) Pop Art (40) Neo Expressionism (1) Generate Timeline fin roccoco The past perfect is formed by combining the auxiliary verb "had" with the past participle. I had studied. He had written a letter to María. We had been stranded for six days. Because the past perfect is a compound tense, two verbs are required: the main verb and the auxiliary verb. I had studied. (main verb: studied ; auxiliary verb: had) He had written a letter to María. (main verb: written ; auxiliary verb: had) We had been stranded for six days. (main verb: been ; auxiliary verb: had) In Spanish, the past perfect tense is formed by using the imperfect tense of the auxiliary verb "haber" with the past participle. Haber is conjugated as follows: había habías había habíamos habíais habían You have already learned in a previous lesson that the past participle is formed by dropping the infinitive ending and adding either -ado or -ido. Remember, some past participles are irregular. The following examples all use the past participle for the verb "vivir." (yo) Había vivido. I had lived. (tú) Habías vivido. You had lived. (él) Había vivido. He had lived. (nosotros) Habíamos vivido. We had lived. (vosotros) Habíais vivido. You-all had lived. (ellos) Habían vivido. They had lived. LA MÚSICA SE ESPAÑA The music of Spain has a long history and has played an important part in the development of western music. It has had a particularly strong influence upon Latin American music. The music of Spain is often associated abroad with traditions like flamenco and the classical guitar but Spanish music is, in fact, diverse from region to region. Flamenco, for example, is an Andalusian musical genre from the south of the country. In contrast, the music in the north-western regions is centred on the use of bagpipes, while the nearby Basque region, with its own traditional styles, is different again, as are traditional styles of music in Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia, Castile and León. Spain has also played an important role within the history of western classical music, particularly in its early phase from the 15th to the 17th centuries; ranging from a composer like Tomás Luis de Victoria, the zarzuela of Spanish opera, the ballet of Manuel de Falla, to the classical guitar music of Pepe Romero. Nowadays, like elsewhere, the different styles of commercial popular music dominate. Origins of the Music of Spain Early history Cantigas de Santa maría, ç medieval Spain In Spain, several very different cultural streams came together in the first centuries of the Christian era: the Roman culture, which was dominant for several hundred years, and which brought with it the music and ideas of Ancient Greece; early Christians, who had their own version of the Roman Rite; the Visigoths, a Germanic people who overran the Iberian peninsula in the 5th century; Jews of the diaspora; and eventually the Moors and Arabs. Determining exactly the various influences is, after more than two thousand years of internal and external influences and developments, impossible but the result has been a large number of unique musical traditions. Isidore of Seville wrote about music in the 6th century. His influences were predominantly Greek, and yet he was an original thinker, and recorded some of the first information about the early music of the Christian church. He perhaps is most famous in music history for declaring that it was not possible to notate sounds—an assertion which reveals his ignorance of the notational system of ancient Greece, so that knowledge had been lost by the time he was writing. Codex Las Huelgas, a medieval Spanish music manuscript, circa 1300 AD. The Moors of Al-Andalus were usually relatively tolerant of Christianity and Judaism, especially during the first three centuries of their long presence in the Iberian peninsula, during which Christian and Jewish music continued to flourish. Music notation was developed in Spain as early as the eighth century (the so-called Visigothic neumes) to notate the chant and other sacred music of the Christian church, but this obscure notation has not yet been deciphered by scholars, and exists only in small fragments. The music of the early medieval Christian church in Spain is known misleadingly as the "Mozarabic Chant". The chant developed in isolation prior to the Islamic invasion and was not subject to the Papacy's enforcement of the Gregorian chant as the standard chant around the time of Charlemagne, by which time the Muslim's had conquered most of the Iberian peninsula. As the Christian reconquista progressed, these chants were almost entirely replaced by the Gregorian standard, once Rome had regained control of the Iberian churches. The style of Spanish popular songs of the time is presumed to have been heavily influenced by Moorish music, especially in the south, but as much of the country still spoke various Latin dialects while under Moorish rule (known today as Mozarabic) earlier musical folk styles from the pre-Islamic period continued in the countryside where most of the population lived, in just the same way as the Mozarabic Chant continued to flourish in the churches. In the royal Christian courts of the reconquistors, the music, like the Cantigas de Santa Maria, also absorbed Moorish influences. Other important medieval sources include the Codex Calixtinus collection from Santiago de Compostela and the Codex Las Huelgas from Burgos. The socalled Llibre Vermell de Montserrat (red book) is an important devotional collection from the 14th century. Renaissance and Baroque In the early Renaissance, Mateo Flecha el viejo and the Castilian dramatist Juan del Encina rank among the main composers in the post-Ars Nova period. Some renaissance songbooks are the Cancionero de Palacio, the Cancionero de Medinaceli, the Cancionero de Upsala (it is kept in Carolina Rediviva library), the Cancionero de la Colombina, and the later Cancionero de la Sablonara. The organist Antonio de Cabezón stands out for his keyboard compositions and mastery. Early 16th century polyphonic vocal style developed in Spain was closely related to the style of the Franco-Flemish composers. Melting of styles occurred during the period when the Holy Roman Empire and Burgundy were part of the dominions under Charles I (king of Spain from 1516 to 1556), since composers from the North both visited Spain, and native Spaniards travelled within the empire, which extended to the Netherlands, Germany and Italy. Music for vihuela by Luis de Milán, Alonso Mudarra and Luis de Narváez stands as one of the main achievements of the period. The Aragonese Gaspar Sanz was the author of the first learning method for guitar. The great Spanish composers of the Renaissance included Francisco Guerrero and Cristóbal de Morales, both of whom spent a significant portion of their careers in Rome. The great Spanish composer of the late Renaissance, who reached a level of polyphonic perfection and expressive intensity equal or even superior to Palestrina and Lassus, was Tomás Luis de Victoria, who also spent much of his life in Rome. Most Spanish composers returned home late in their careers to spread their musical knowledge in their native land or at the service of the Court of Philip II at the late 16th century. 18th to 20th centuries Front cover of book: Escuela Música según la práctica moderna published in 1723-1724 By the end of the 17th century the "classical" musical culture of Spain was in decline, and was to remain that way until the 19th century. Classicism in Spain, when it arrived, was inspired on Italian models, as in the works of Antonio Soler. Some outstanding Italian composers as Domenico Scarlatti or Luigi Boccherini were appointed at the Madrid court. The short-lived Juan Crisóstomo Arriaga is credited as the main beginner of Romantic sinfonism in Spain. Fernando Sor, Dionisio Aguado, Francisco Tárrega and Miguel Llobet are known as composers of guitar music. Fine literature for violin was created by Pablo Sarasate and Jesús de Monasterio. Zarzuela, a native form of opera that includes spoken dialogue, is a secular musical genre which developed in the mid 17th century, flourishing most importantly in the century after 1850. Francisco Asenjo Barbieri was a key figure in the development of the romantic zarzuela; whilst later composers such as Ruperto Chapí, Federico Chueca and Tomás Bretón brought the genre to its late 19th-century apogee. Leading 20th century zarzuela composers included Pablo Sorozábal and Federico Moreno Torroba. Musical creativity mainly moved into areas of popular music until the nationalist revival of the late Romantic era. Spanish composers of this period include Felipe Pedrell, Isaac Albéniz, Enrique Granados, Joaquín Turina, Manuel de Falla, Jesús Guridi, Ernesto Halffter, Federico Mompou, Salvador Bacarisse, and Joaquín Rodrigo. Music by Region Spain's regions have their own distinctive musical traditions. There is also a movement of singersongwriters with politically active lyrics, paralleling similar developments across Latin America and Portugal. As an example of open-mindedness and use of the available sources, singer and composer Eliseo Parra (b 1949) can afford to record music from the Basque country and from Castile. Andalusia Flamenco dancing in Seville. Music of Andalusia Though Andalusia is best known for flamenco music, there is also a tradition of gaita rociera (tabor pipe) music in western Andalusia and a distinct violin and plucked-string type of band music known as panda de verdiales in Málaga. Panda de Verdiales in Málaga. Sevillanas is related to flamenco and most flamenco performers have at least one classic sevillana in their repertoire. The style originated as a medieval Castilian dance, called the seguidilla, which was flamenconized in the 19th century. Today, this lively couples' dance is popular in most parts of Spain, though the dance is often associated with the city of Seville's famous Easter feria. The region has also produced singer-songwriters like Javier Ruibal and Carlos Cano, who revived a traditional music called copla. Catalan Kiko Veneno and Joaquín Sabina are popular performers in a distinctly Spanish-style rock music, while Sephardic musicians like Aurora Moreno, Luís Delgado and Rosa Zaragoza keep alive-and-well Andalusian Sephardic music. Aragon Aragonese jota dancing Music of Aragon Jota, popular across Spain, might have its historical roots in the southern part of Aragon. Jota instruments include the castanets, guitar, bandurria, tambourines and sometimes the flute. Aragonese music can be characterized by a dense percussive element that some have tried to attribute to an influence from the North African Berbers. The guitarro, a unique kind of small guitar also seen in Murcia, seems Aragonese in origin. Besides its music for stick-dances and dulzaina (shawm), Aragon has its own gaita de boto (bagpipes) and chiflo (tabor pipe). As in the Basque country, Aragonese chiflo can be played along to a chicotén string-drum (psaltery) rhythm. Asturias, Cantabria and Galicia Music of Galicia, Cantabria and Asturias An Asturian gaitera (bagpipe player) Northwest Spain (Asturias, Galicia and Cantabria) is home to a distinct musical tradition extending back into the Middle Ages. The region's signature instrument is the gaita (bagpipe). The gaita is often accompanied by a snare drum, called the tamboril, and played in processional marches. Other instruments include the requinta, a kind of fife, as well as harps, fiddles, rebec and zanfona (hurdygurdy). The music itself runs the gamut from uptempo muiñieras to stately marches. As in the nearby Basque Country, Cantabrian music also features intrincate arch and stick dances but the tabor pipe does not play as an important role as it does in Basque music. There are local festivals celebrating a presumed musical survival of the region's pre-Roman Celtic culture, of which Ortigueira's Festival del Mundo Celta is especially important. Drum and bagpipe couples range among the most beloved kinds of Galician music, that also includes popular bands like Milladoiro. Groups of pandereteiras are traditional sets of singing women that play tambourines and sing. The bagpipe virtuosos Carlos Núñez and Susana Seivane are especially popular performers. Traditionally, Galician music characteristically included a type of chanting song known as alalas. Alalas may include instrumental interludes, and are believed to have a very long history; most of it is clearly legendary. Asturias is also home to popular musicians such as José Ángel Hevia (another virtuoso bagpiper) and famous group Llan de Cubel. Circle dances using a 6/8 tambourine rhythm are also a hallmark of this area. Vocal asturianadas show melismatic ornamentations similar to those of other parts of the Iberian Peninsula. There are many festivals, such as "Folixa na Primavera" (April, in Mieres), "Intercelticu d'Avilés" (Interceltic festival of Avilés, in July), as well as many "Celtic nights" in Asturias. Balearic Islands Music of the Balearic Islands In the Balearic Islands, Xeremiers or colla de xeremiers is a traditional ensemble that consists of flabiol (a five-hole tabor pipe) and xeremies (bagpipes). Majorca's Maria del Mar Bonet was one of the most influential artists of nova canço, known for her political and social lyrics. Tomeu Penya, Biel Majoral, Cerebros Exprimidos and Joan Bibiloni are also popular. Basque Country Basque music Ezpatadantza of the Basque Country. The most popular kind of Basque music is called after the dance trikitixa, which is based on the accordion and tambourine. Popular performers are Joseba Tapia and Kepa Junkera. Very appreciated folk instruments are txistu (a tabor pipe similar to Occitanian galoubet recorder), alboka (a double clarinet played in circular-breathing technique, similar to other Mediterranean instruments like - launeddas) and txalaparta (a huge xylophone, similar to the Romanian toacă and played by two performers in a fascinating game-performance). As in many parts of the Iberian peninsula, there are ritual dances with sticks, swords and vegetal arches. Other popular dances are fandango, jota and 5/8 zortziko. Basques on both sides of the Spanish-French border have been known for their singing since the Middle Ages, and a surge of Basque nationalism at the end of the 19th century led to the establishment of large Basque-language choirs that helped preserve their language and songs. Even during the persecution of the Francisco Franco era (1939–1975), when the Basque language was outlawed, traditional songs and dances were defiantly preserved in secret. They continue to thrive despite the popularity of commercially marketed pop. Canary Islands Music of the Canary Islands In the Canary Islands, Isa, a local kind of Jota, is now popular, and Latin American musical (Cuban) influences are quite widespread, especially in the presence of the charango (a kind of guitar). Timple, the local name for ukulele / cavaquinho, is commonly seen in plucked string bands. A popular set in El Hierro island consists of drums and wooden fifes (pito herreño). Tabor pipe is customary in some ritual dances in Tenerife island. Castile, Madrid and León Music of Castile, Madrid and León A large inland region, Castile, Madrid and Leon were Celtiberian country before its annexation and cultural latinization by the Roman Empire but it is extremely doubtful that anything from the musical traditions of the Celtic era have survived. Ever since, the area has been a musical melting pot; including Roman, Visigothic, French, Italian, Gypsy, Moorish, and Jewish influences but the most important influences are the longstanding and continuing ones from the surrounding Spanish regions as well as from Portugal to the west. Areas within Castile and León generally tend to have more musical affinity with neighbouring regions than with other, more distant, parts of Castile and León. This has given the region a locally diverse musical tradition. Jota is popular, but is uniquely slow in Castile and León, unlike its more energetic Aragonese version. Instrumentation also varies much from the one in Aragon. Northern León, that shares a language relationship with a region in northern Portugal and the Spanish regions of Asturias and Galicia, also shares their musical influences. Here, the gaita (bagpipe) and tabor pipe playing traditions are prominent. In most of Castile, there is a strong tradition of dance music for dulzaina (shawm) and rondalla groups. Popular rhythms include 5/8 charrada and circle dances, jota and habas verdes. As in many other parts of the Iberian peninsula, ritual dances include paloteos (stick dances). Salamanca is known as the home of tuna, a serenade played with guitars and tambourines, mostly by students dressed in medieval clothing. Madrid is known for its chotis music, a local variation to the 19th century schottische dance. Flamenco, although not considered native, is popular among some urbanites but is mainly confined to Madrid. Catalonia Music of Catalonia The Sardana of Catalonia Though Catalonia is best known for sardana music played by a cobla, there are other traditional styles of dance music like ball de bastons (stick-dances), galops, ball de gitanes. Music is at the forefront in cercaviles and celebrations similar to Patum in Berga. Flabiol (a five-hole tabor pipe), gralla or dolçaina (a shawm) and sac de gemecs (a local bagpipe) are traditional folk instruments that make part of some coblas. Catalan gipsies created their own style of rumba called rumba catalana which is a popular style that's similar to flamenco, but not technically part of the flamenco canon. The rumba catalana originated in Barcelona when the rumba and other Afro-Cuban styles arrived from Cuba in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Catalan performers adapted them to the flamenco format and made it their own. Though often dismissed by aficionados as "fake" flamenco, rumba catalana remains wildly popular to this day. The havaneres singers remain popular. Nowadays, young people cultivate Rock Català popular music, as some years ago the Nova Cançó was relevant. Extremadura Music of Extremadura Having long been the poorest part of Spain, Extremadura is a largely rural region known for the Portuguese influence on its music. As in the northern regions of Spain, there is a rich repertoire for tabor pipe music. The zambomba friction-drum (similar to Portuguese sarronca or Brazilian cuica) is played by pulling on a rope which is inside the drum. It is found throughout Spain. The jota is common, here played with triangles, castanets, guitars, tambourines, accordions and zambombas. Murcia Music of Murcia Murcia is a region in the south-east of Spain which, historically, experienced considerable Moorish colonisation, is similar in many respects to its neighbour, Andalusia. The guitar-accompanied cante jondo Flamenco style is especially associated with Murcia as are rondallas, plucked-string bands. Christian songs, such as the Auroras, are traditionally sung a cappella, sometimes accompanied by the sound of church bells, and cuadrillas are festive songs primarily played during holidays, like Christmas. Navarre and La Rioja Music of Navarre and La Rioja Navarre and La Rioja are small northern regions with diverse cultural elements. Northern Navarre is Basque in language, while the Southern section shares more Aragonese features. The jota is also known in both Navarre and La Rioja. Both regions have rich dance and dulzaina (shawm) traditions. Txistu (tabor pipe) and dulzaina ensembles are very popular in the public celebrations of Navarre. Valencia Music of Valencia Traditional music from Valencia is characteristically Mediterranean in origin. Valencia also has its local kind of Jota. Moreover, Valencia has a high reputation for musical innovation, and performing brass bands called bandes are common, with one appearing in almost every town. Dolçaina (shawm) is widely found Valencia also shares some traditional dances with other Iberian areas, like for instance, the ball de bastons (stick-dances). The group Al Tall is also well-known, experimenting with the Berber band Muluk El Hwa, and revitalizing traditional Valencian music, following the Riproposta Italian musical movement. Popular music Although Spanish pop music is currently flourishing, the industry suffered for many years under Francisco Franco's regime, with few outlets for Spanish performers during the 1930s through the 1970s. Regardless, American and British music, especially rock and roll, had a profound impact on Spanish audiences and musicians The Benidorm International Song Festival, founded in 1959 in Benidorm, became an early venue where musicians could perform contemporary music for Spanish audiences. Inspired by the Italian San Remo Music Festival, this festival was followed by a wave of similar music festivals in places like Barcelona, Majorca and the Canary Islands. Many of the major Spanish pop stars of the era rose to fame through these music festivals. An injured Real Madrid player-turned-singer, for example, became the world-famous Julio Iglesias. During the 1960s and early 1970s, tourism boomed, bringing yet more musical styles from the rest of the continent and abroad. However, it wasn't until the 1980s that Spain's burgeoning pop music industry began to take off. During this time a cultural reawakening known as La Movida Madrileña produced an explosion of new art, film and music that reverberates to this day. Once derivative and out-of-step with AngloAmerican musical trends, contemporary Spanish pop is as risky and cutting-edge as any scene in the world, and encompasses everything from shiny electronica and Eurodisco, to homegrown blues, rock, punk, ska, reggae and hip-hop to name a few. Artist like Enrique Iglesias or Alejandro Sanz have become successful internationally, selling million of albums worldwide and winning major music awards such as the coveted Grammy Award. Ye-Yé Yé-yé From the English pop-refrain words "yeah-yeah", ye-yé was a French-coined term which Spanish language appropriated to refer to uptempo, "spirit lifting" pop music. It mainly consisted of fusions of American rock from the early 60s (such as twist) and British beat music. Concha Velasco, a talented singer and movie star, launched the scene with her 1965 hit "La Chica YeYé", though there had been hits earlier by female singers like Karina (1963). The earliest stars were an imitation of French pop, at the time itself an imitation of American and British pop and rock. Flamenco rhythms, however, sometimes made the sound distinctively Spanish. From this first generation of Spanish pop singers, Rosalia´s 1965 hit "Flamenco" sounded most distinctively Spanish. Performers This section is in a list format that may be better presented using prose. You can help by converting this section to prose, Realidades 3 ¡Home Journal No Olviden Uds.! ¡Home Journal No Olviden Uds.! ¡Home Journal No Olviden Uds.! Due day of final!!!!! Realidades 3 EL PAQUETE de Capítulo 5 Página 63 Capítulo 5 ¡CAPÍTULO 5! FINAL EXAM!!!!!