Bartolome De Las Casas

advertisement

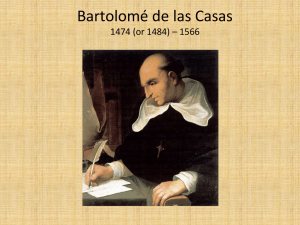

U.S. History Mr. Kevin W. Walsh Bartolomé de Las Casas and his Defense of the Indians Bartolomé de Las Casas (1484-1576) was born in Seville, and, at age eighteen, left Spain for the New World where he took part in the colonization of Cuba. The barbarity of the Spanish conquistadores shocked him, bringing about a conversion and entry into the Dominican order. Thereafter, he devoted himself to the defense of the Indians, and the cataloguing of Spanish atrocities against them. The Spanish Crown had long been concerned with the morality of conquest, and employed theologians and jurists to advise on behavior. One result of this was the Requirement (Requerimiento), a document which had to be read out to the Indians prior to an attack. (This was often read in Spanish to Indians who did not understand the language, or was even proclaimed out of earshot to them. It also resulted in an institution known as the encomienda. By this official Spanish policy, set by Ferdinand and Isabella, land belonged to the Spanish Crown and the Indians were compelled to work it on behalf of their Spanish master or encomendero. In return, however, they were to be afforded the protection of the Crown, instruction in the Christian faith and a small wage. (Las Casas himself benefited from this system both in Hispaniola and Cuba.) In practice, however, the Indians were treated in a horrific way - enslaved, starved, tortured, hunted down and massacred in huge numbers. This experience produced a despair resulting in suicide, infanticide and induced abortion amongst the Indians. Las Casas was radical but not heretical - he believed that Columbus was an instrument of God to bring the Gospel to the New World and did not advocate revolt against the Spanish Crown, whose legitimacy to rule in South America he accepted. The behavior of its representatives, however, was not in accord with either Christianity or official Spanish policy in his view, and needed to be recorded for Europe’s education. As well as recording the brutality of colonization, his books argued against the concept of the Indian as an inferior race. Las Casas argued that they were indeed ‘fully rational beings with a culture which, though certainly “primitive” in its technology and in a large number of its practices, was equal to anything which the Old World had produced.’ (Griffin 1992: xxviii). His ideas had little immediate effect on changing Spanish attitudes in South America - the lust for gold was stronger than the recognition of religious or moral justice amongst the conquistadores. In the longer term, however, his books and actions earned him the title ‘Defender and Apostle to the Indians’. The following comes from ‘A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies’ and is the section devoted to Santa Marta. ‘The natives of the province of Santa Marta had a great deal of gold, the province and its immediate neighbors being rich in the metal and the people who lived there having the will and the know-how to extract it. And this is the reason why, from 1498 right down to today, in 1542, the region has attracted an uninterrupted series of Spanish plunderers who have done nothing but sail there, attack, murder and rob the people, steal their gold and sail back again. Each expedition in turn - and there have been many over the years - has overrun the area, causing untold harm and a monstrous death-toll, and perpetrating countless atrocities. Until 1523, it was for the most part only the coastal strip that was blighted, and the countryside for a few leagues inland; but, in that year, a number of these Spanish brigands established a permanent settlement in the area and, since the region was, as we have said, extremely rich, that settlement witnessed the arrival of one commander after another, each set on outdoing his predecessor in villainy and cruelty, as though to prove the validity of the principle we outlined earlier. The year 1529 saw the arrival of a considerable force under the command of one such Spaniard, a grimly determined individual, with no fear of God and not an ounce of compassion for his fellow-men; he proceeded to outshine all who had gone before him in the arts of terror, murder, and the most appalling cruelty. In the six or seven years he and his men were in the province, they amassed a huge fortune. After his death - and he died without the benefit of confession and in full flight from his official residence - there came other robbers and murderers who wiped out those of the local population who had survived the attentions of their predecessors. They extended their reign of terror far inland, plundering and devastating whole provinces, killing or capturing the people who lived there in much the same way as we have seen happening elsewhere, torturing chiefs and vassals alike in order to discover the whereabouts of the gold and, as we have said, far outdoing, in both quantity and quality, even the awfulness of those who had gone before them. This they did to such effect that they contrived to depopulate, between 1529 and today, an area of over four hundred leagues which was once as densely inhabited as any other.