- UM Research Repository

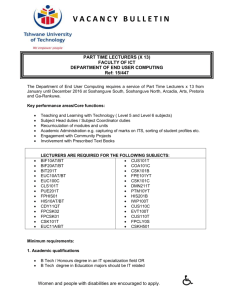

advertisement

Creative Teaching for Equality and Equity Across Cultures Ananda Kumar Palaniappan1, Chanisa Tantixalerm2, Adelina Asmawi1, Lau Poh Li1, Pradip Kumar Mishra1 1 University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand 2 Abstract Addressing issues relating to equality and equity in educational experiences requires creative approaches and strategies. Often teachers are unable to address this aspect of their teaching. However, creative teachers, given their creative predispositions, might be better able to address these issues as they tend to generate more creative teaching approaches. Very few studies have investigated how creative teachers address these issues in their various forms and across cultures. There is a need to address situations where some learners require more challenging tasks than others and also when learners are culturally diverse. Creative teachers may be best placed to address these issues since they would be better able to come up with creative teaching strategies. There may also be cultural differences in teaching strategies since teacher-learner interactions have been found to differ across cultures. In this study, creative lecturers in Malaysia and Thailand were first identified using student ratings. These lecturers were then observed in their classrooms and interviewed on how they addressed issues relating to providing equitable education and the creative strategies they employed. Focus group discussions with their learners were also held to triangulate the findings. Findings show that creative teachers address issues of equality and equity in six areas, namely, Resources, Teaching strategies, Assessment, Language, Activities and Open-mindedness. Creative teachers are able to creatively design or adapt resources and activities which the diverse students are free to choose according to their needs. They have a repertoire of teaching strategies to accommodate students’ learning styles and employ culturally responsive communication styles. Being open-minded, they allow a range of assessment approaches that cater to student diversity. Although Malaysian and Thai creative lecturers address equality and equity issues in similar areas, their approaches in executing these creative strategies differ. These findings suggest that it may be necessary for teacher educators in Malaysia and Thailand to look into these six areas which may help them to address equity and equality issues creatively among learners. This paper concludes with some recommendations for further research. Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 Corresponding author: Prof. Dr. Ananda Kumar Palaniappan Department of Educational Psychology and Counseling, Faculty of Education, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Email: ananda4989@yahoo.com Telephone: +6-019-9310956 Highlights: Creative lecturers addressed equality and equity in twenty six areas. Six main themes were derived from these areas Resources, Teaching strategies and Activities were identified as the main themes. Assessment, Language, and Open-mindedness were also thematically important. Malaysian and Thai lecturers used similar strategies, but with different approaches. Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 Creative Teaching for Equality and Equity across Cultures 1. Introduction The concept of equality and equity in education has contributed vastly to the humanistic viewpoint of teaching and learning in schools and institutions of higher learning. This is in line with Aristotle’s view of treating equals equally and unequals unequally. Teachers are expected to design creative and innovative teaching and learning experiences to cater for all learners taking into account the various areas of differences. However, this is not the case in most schools and institutions of higher learning (Derounian, 2011). For example, academically advanced learners are preferred to those who are not. Learners who are creative or question the status quo (Beghetto, 2007) appear unappealing to teachers (Cheng, 2011; Westby & Dawson, 1995) while those who are conforming are held in high regard. In some cases, slow learners and even the gifted are neglected (Yewchuk, 1998) sometimes due to the lack of knowledge and skills on how to cater for them (Munro, 2012). Although teachers may try their best to cater for all learners and also address their individual differences, this can be very challenging (Daniels, 2013). Creative teachers are able to generate and implement ideas to ensure there is equality and equity in the classroom however formidable the task (Reilly, Lilly, Bramwell, & Kronish, 2011). When it comes to curriculum, teaching and assessment, they know that one size does not fit all. While a number of studies have been done on creative teaching (e.g., Horng, Hong, Lin, Lin, Chang, & Chu, 2005; Rinkevich, 2011) and on equality and equity in education (e.g., Blanchet-Cohen, & Reilly, 2013; Reed & Oppong, 2005), hardly any studies deal with how creative teachers address equality and equity issues in the classroom. A review of literature has revealed a dearth of information on how creative university lecturers address equality and equity issues in their classes, especially in institutions of higher learning where increasing learner diversity resulted from internationalization of education. In this paper we aim at filling this gap in knowledge and stimulate further research by observing and interviewing creative lecturers. These lecturers have been nominated as creative by their students, for the creative strategies employed to ensure equality and equity in their classes. Secondly, we elucidate the cultural differences in how creative lecturers address equality and equity as certain cultures may be sensitive to these issues in schools (Misawa, 2010; Paul-Binyamin & Reingold, 2013). Our findings may have implications for teachers, curriculum developers and policy planners in a multicultural education system. Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 1.1 Research questions Based on the preceding rationale of the study, the research questions that this study intends to address are: i) ii) 2. In what areas do creative teachers address equity and equality issues? Are there cultural differences in these areas of creative teaching between Malaysian and Thai creative lecturers? Creative Teaching Creative teaching has been defined in varied ways (see Gibson, 2010, for example). This could be due to the nebulous nature of creativity itself (McWilliam & Haukka, 2008) resulting in a lack of a universally accepted definition of creativity (Clouder, Oliver, & Tait, 2008; Pope, 2005; Reid & Petocz, 2004; Sousa, 2007). Most definitions have focused on teaching creativity (i.e., teaching creative thinking with the aim of enhancing creative thinking skills among students). Another aspect that has been neglected in most definitions of creative teaching is “teaching creatively”. Teaching creatively is defined as a process of incorporating creative processes and components of creativity in the teaching process. In also incorporates the lecturers’ creative personality characteristics and creative thinking processes which they use to design the instructional strategies to enhance learning and motivate students. Examples of creative teaching would be activities that promote “creative problem solving, creative association, invention, creative imagery, and various forms of divergent thinking” (Chan, 2007, p. 5). Hence, teaching creatively is defined as a process of designing and strategizing instruction such that it facilitates thinking skills especially creative thinking skills among students. For example, lecturers teaching creativity to enhance originality in thinking in a language class may ask students to develop a new ending for a favorite story or rewrite an ending to a story they know. It can also be a task to put students in the characters’ shoes and ask them to look at the piece of literature from their own perspective. Hence, creative teaching is now seen as both teaching creatively and teaching creativity (NACCCE, 1999). Based on these two aspects of creative teaching, Palaniappan (2008) proposed a systems model of creative teaching (Figure 1). This holistic approach is aimed at enabling lecturers, trainers, school and university administrators as well as policy makers to direct their attention to a holistic view of creative teaching instead of focusing only on the lecturer behaviors and activities in the class. In the systems view of creative teaching, for creative teaching to take place, it is crucial that all significant factors affecting creative teaching are taken into account when designing the creative teaching and learning process. These significant factors can be categorized as those within the school environment and those outside it (Cheng, Chuang & Bennington, 2011). Significant factors within the school environment include the learners, lecturers, curriculum and lecturer evaluations by the administrators (Davidovitch & Milgram, 2006). The success of any creative Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 teaching strategy depends on the learner characteristics including, among others, the learners’ creative personality characteristics, creative motivation and creativity. Figure 1. A systems view of Creative Teaching model (Palaniappan, 2008) The lecturer variable is a crucial component in creative teaching. Many factors relating to the lecturer determine whether creative teaching will take place or not. Among them are lecturers’ personality characteristics (Cachia & Ferrari, 2010) including their level of independence, attitudes (Davis et al., 2014), and motivation toward teaching creativity and creatively, lecturers’ own level of creativity, and their pedagogical experiences. Curriculum plays an equally important role. It should set the stage for creative teaching. There should be a deliberate attempt to provide for creative presentation of content and also to enhance the students’ creativity. For example, the curriculum should indicate for each sections of the topic being taught, the various pedagogical methods lecturers can use or provide opportunities for lecturers to use their own creativity to explore other strategies to present the material. All three above mentioned factors depend on the school environment. The school environment encompasses other lecturers and colleagues, the principal, and other students as well as the policies Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 governing the day to day running of the school and school infrastructure made available to the lecturers and students. For example, support from other lecturers form a valuable source of creative energy for the lecturer. A supportive principal who is willing to allow lecturers to try unconventional teaching methods is also crucial. Creative students also provide the creative climate that lecturers and other students need to grow creatively. The way students are treated will determine the creative attitude they can develop in solving any problem or brain storming any issue. A lecturer-centered classroom with creative teaching will fail to generate creativity in students unless these students are empowered to try out the creative components in every lesson on their own. Therefore the learner component in the systems view model is as important as the lecturer or the curriculum factor. Students grouping together to think of an easier way to raise funds for a good cause or design a new way to build an intelligent traffic system for the local town council are just some of the creative activities that can be organized. Among the factors outside the school environment vital for enabling creative teaching in school are the parents, government policies, the future employers and the industry demands on the schools. Parents play a vital role in creative teaching. Lecturers wishing to take students on field trips which expose students to a multitude of stimuli crucial for creative thinking would need parental support. Government policies relating to education especially in curriculum development and reference text for lecturers and textbooks for students play an equally important role. Lecturers may not be motivated to teach creatively if they are constrained by the curriculum and the strict policies regarding testing and evaluation. Research has shown that rigorous testing may kill students’ creativity as they will be focusing more on studying for examinations rather than reflecting and exploring the world around them purposefully for the benefit of society. Employer or industry needs determine what is emphasized in schools especially in industry oriented schools. If employers only seek creative and innovative individuals, the government and universities will be duty bound to produce creative and innovative employees. For example, if IT companies need employees who are able to foresee future software and hardware needs and design innovative software and hardware, they will only seek out and employ creative individuals. 3. Creative Teaching for equality and equity Issues relating to equality and equity as well as the provision of more equitable opportunities to all learners have continually shaped educational policies and teacher education programs. All learners are equally able to succeed when given the most appropriate instruction and classroom environment. This humanistic view has resulted in inclusive education for the whole range of learners, from the gifted / talented to children with special needs and also culturally, linguistically and socio-economically disadvantaged learners. However, this is not easily achieved in the classroom, because in reality, teachers and lecturers often have to teach a large number of diverse learners with limited time and resources (Achinstein, & Athanases, 2005). Teachers need to be creative in completing the content and catering for learner differences all within a limited class time. Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 Creative teaching has been defined in various ways (see Gibson, 2010). This partly stems from the fact that there is no universally accepted definition of creativity (Clouder, Oliver, & Tait, 2008; Pope, 2005; Prentice, 2000; Reid & Petocz, 2004; Sousa, 2007). Creativity has been defined as the process, a personality characteristic or the production of something original and useful (Rasulzada & Dackert, 2009). Rhodes’s (1961) theoretical framework derived from the classification of creativity definitions comprised four dimensions, namely Process, Person, Product and Press or the 4P’s. His Process, Person and Product dimensions are similar to those mentioned by Rasulzada and Dackert (2009) while the Press dimension refers to conditions facilitating creativity. Rhode’s (1961) model provided valuable input for the Creative Teaching Model developed by Palaniappan (2008) which also incorporated Torrance’s (1990) creativity dimensions of Originality, Fluency, Flexibility and Elaboration. This model provided the theoretical basis for the creative teaching framework for this study. The National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education (NACCCE) report (1999) has defined creative teaching as comprising teaching creatively and teaching for creativity. The former involves incorporating creative teaching strategies while the latter involves strategies aimed at enhancing learner creativity. Creative teachers tend to exhibit both in different degrees especially in addressing issues relating to equality and equity. For example, some creative teachers focus more on using novel and innovative strategies to attract student attention (Lou, Chen, Tsai, Tseng, & Shih, 2012) while others choose strategies aimed at enhancing creative thinking skills, such as inquiry-based teaching (DeHaan, 2009) and problem-based learning (Awang & Ramly, 2008). Other researchers emphasize on developing students’ creative personality characteristics such as being inquisitive, taking responsible risks (Costa & Kallick, 2009) and being curious (Cheng, 2011). Developed from a comprehensive review of literature, Palaniappan’s (2008) model provides a holistic view of creative teaching that informed this study on creative ways teachers address equality and equity issues. These reviews also revealed some common characteristics of creative teaching that appear to be relevant in addressing the equality and equity issues in education. 3.1 Creative teaching strategies for equality and equity Literature has shown that creative teachers do things differently and more efficiently in many areas. They tend to be able to use the right teaching strategy taking into account the need to address individual differences and lack of time and resources (Ambrose, 2005). Creative lecturers have a natural tendency to cater to diverse learners (Rejskind, 2000; Simplicio, 2000). They are better able to help learners with diverse learning styles. This is because some learners learn better with just oral explanations while others require real-life examples, hands-on practical activities in the language they understand or some forms of analogy to understand concepts (Grainger, Barnes, & Scoffham, 2004). Creative teachers are flexible enough to generate various forms of teaching aids that facilitate learning among diverse learners (Grainger et al., 2004). Others empower learners with freedom to choose materials that interest them (Gibson, 2010). Their flexible class structure allows them to cater for diverse learners (Davis, Jindal-Snape, Digby, Howe, Collier, & Hay, 2014). Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 Events involving people from the creative arts (Jeffrey, 2006) like artists and sculptors, are also used in the school curriculum to cater for creative learners. Situations encouraging teacher-learner dialogue so that learners find their own ways to solve problems and produce creative products also cater for learners who need challenging tasks (Tanggard, 2011). Teachers who use different teaching modalities, analogies, metaphors (Gibson, 2010) and other strategies to cater for all types learners tend to foster equality in the class (Grainger et al., 2004). Some creative teachers’ playful nature (Grainger et al., 2004; Kangas, 2010) allows them to explore various creative strategies to get learner attention. Creating classroom conditions which support different learner abilities is one way creative teachers can address equity in the classroom. These strategies including provision of cognitively challenging activities in a student-centered teaching environment have been found to enhance academic achievement (Stritikus & Varghese, 2010). 3.2 Lecturer-learner interactions Lecturers’ language, attitudes and behaviors play an important role in addressing equity and equality issues in the classroom. Creative lecturers are able to harness their creativity to address these issues even if they have to follow very rigid curriculum requirements (Sawyer, 2004). The lecturers’ body language also indicate that they appreciate and value students’ creativity (Eason, Giannangelo, & Franceschini III, 2009). Using different languages which the diverse students are familiar with helps to enhance positive classroom experiences (Stritikus & Varghese, 2010). Creative teachers who are familiar with these languages use different languages to cater for their linguistically diverse students. Often, creative lecturers do this spontaneously and with minimal effort. They also have high expectations of being able to address diverse students’ needs and are able to teach students in the best way possible (Cooley, 2007). They tend to adopt a culturally responsive communication style (Brown, 2007; Gay, 2000) where they use their own cultural knowledge of ethnically diverse students together with their own prior experiences to create an equitable classroom environment. 3.3 Assessment Lecturers always face a dilemma as to whether they should utilize traditional modes of assessment or use innovative assessment approaches taking into account learner diversity. Creative teachers have been seen to address issues relating to equality and equity in assessment in original ways (Reilly, Lilly, Bramwell, & Kronish, 2011; Woods, & Jeffrey, 1996). They tend to choose from a repertoire of varied assessment strategies. They delight in giving learners the freedom and flexibility to choose how they wish to be assessed (Gibson, 2010) or in modifying their assessment strategies to suit learner needs and learning styles. Instead of the traditional assessment methods such as end of term exams, they use innovative and authentic assessment that are intellectually challenging and relevant to daily life issues faced by learners (Ramsden, 2003). Some creative lecturers give students freedom to choose assignments and also how they wish to deliver them, either via presentation, digital reports or as exhibits for peer evaluation. Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 3.4 Creative teaching across cultures Many countries have taken various initiatives to ensure equality and equity in education at the policy level. In Malaysia, the National Education Blueprint (2013 – 2025) (National Education Blueprint, 2012) is aimed at ensuring equal access to education regardless of race, gender, socioeconomic status, disabilities and location. In Australia, the Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians (2011) provided access to high quality education for all students. In the Thai context, the constitution emphasizes people’s rights to access quality education. Thailand’s efforts to maintain the rights of all people to equal access to quality education are evidenced in the enactment of the Persons with Disabilities Empowerment Act of 2007 which provides legal measures against all types of discrimination (NEP, 2007). Despite these initiatives, equity and equality issues have consistently been highlighted in the mass media and have been found to have worsened (Hazri & Raman, 2012; Levin, 2003; Mohd Roslan, 2010). There is a need for lecturers to understand these issues and how they can address them creatively since “capacity for creative thought and action” is viewed as the engine for cultural change and development (NACCCE, 1999, p. 6). Previous studies have shown that there are cultural differences in creativity (Chan & Chan, 1999; Cheng, 2004; Palaniappan, 1996) and creative teaching (Cheng, 2011). Cultural differences have also been found in the way we view issues of equality and equity (Wiseman, 2008). Hence, it is envisaged that there may be cultural differences in the way creative teachers approach issues of equality and equity. However, there is no research documentation of the creative ways lecturers in different cultures address equality and equity issues in higher education. In this era of globalization and diverse student population in institutions of higher learning, it is imperative that lecturers are knowledgeable in addressing equality and equity issues in all aspects of teaching. Hence, this study compared Malaysian and Thai creative lecturers in their creative teaching and the strategies they employed to enhance student creativity. Understanding the various strategies used in different cultures may provide new insights into the creative ways equity and equality issues are addressed in institutions of higher learning. 4. Methodology For the purpose of this study, four Malaysian universities (two public and two private) and one Thai public university were chosen. Creative lecturers in these universities were first identified by students who nominated lecturers they considered creative using the Lecturer Nomination Questionnaire (LNQ). Lecturers securing the highest votes were then approached to seek their willingness to participate in this study. On obtaining their permission, the classes of 12 creative lecturers in Malaysia and four creative lecturers in Thailand were observed by the researchers trained in the area of creative teaching and teaching for creativity. These researchers used the Class Observation Schedule (COS) to record the lecturers’ strategies in addressing issues relating to equality and equity. These creative lecturers were then interviewed using a Lecturer Interview Protocol (LIP) consisting of some open-ended questions on their teaching strategies and the reasons for using them. Four students from each of these lecturers’ classes volunteered to be in a Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 focus group discussion; they provided valuable information for triangulation as well as confirmation of the lecturers’ creative teaching practices employed to address issues relating to equality and equity. All classroom observations, interviews and focus group discussions were audio-recorded with the permission of the lecturers and students respectively as per the ethics committee’s approval. They were then transcribed and then cross-checked with the recordings by other researchers in the team for transcription accuracy. 4.1 Data analyses The transcriptions were first open-coded using the constant comparison methodology (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Open-codes created as ‘units’ (Lincoln & Guba, 1985) depicted all instances of equity and equality issues addressed by these lecturers. These open-codes were then grouped together into axial codes. Axial codes of all lecturers were tabulated and common themes were then identified. These themes were then referred to the original transcriptions to allow for reflexivity. Member checks were used for additional confirmability and to enhance credibility. To ensure anonymity, the Malaysian creative lecturers were identified as M1 through M12 and the creative Thai lecturers were identified as T1 through T4. 5. Findings In order to answer the first research question: In what areas do creative teachers address equity and equality issues, the lecturers were observed and interviewed. This was followed by focus group discussions with a selected group of students. The transcripts were first open-coded. This opencoding procedure for all transcripts of the creative Malaysian and Thai lecturers yielded 26 axial codes. These axial codes were then named as follows: 1) Teaching aids, 2) Teaching style, 3) Assessment, 4) Lecturer Language, 5) Learner language, 6) Materials presentation, 7) Access to resources, 8) Choice of activities, 9) Tactfulness, 10) Audiovisuals, 11) Interactions, 12) Learner Attitude, 13) Teach to ability, 14) Technology, 15) References, 16) Learner diversity, 17) Course materials, 18) Learner sharing, 19) Out of class teaching, 20) Technology for assessment, 21) Flexibility in assessment, 22) Open-mindedness in assessment, 23) Assessment through play, 24) Use of rewards, 25) Needs-based activities and 26) Challenging activities. Based on the contexts in which they appeared, these axial codes which show areas where creative lecturers addressed equity and equality issues are defined as follows: 1) Teaching aids refers to how materials and tools are created and adapted based on individual differences 2) Teaching style refers to how lecturers teach to individual learning styles thus addressing equity in the class. 3) Assessment refers to how lecturers use creative ways to fairly assess learners. Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 4) Lecturer language refers to how lecturers creatively use non-discriminatory language. 5) Learner language comprises ways lecturers creatively address learners’ language biasness. 6) Material presentation refers to creative ways materials are presented to address equality and equity among diverse learners. 7) Access to resources refers to how lecturers creatively modify materials to make them accessible to learners with varying capabilities. 8) Choice of activities refers to how lecturers allow learners to choose activities to address their preferences and needs. 9) Tactfulness refers to how lecturers creatively promote positive images by maintaining closeness and fairness among diverse learners. 10) Audiovisuals refers to how lecturers minimize bias in the audiovisuals used. 11) Interactions comprises all efforts by lecturers to reduce bias and prejudice in lecturer – learner interactions. 12) Learner attitude refers to creative ways lecturers address learners’ discriminatory attitudes in class. 13) Teach to ability refers to how lecturers creatively teach according to learners’ abilities. 14) Technology refers to how lecturers creatively use computer technology suitable to each individual. 15) References encompass examples from diverse cultures in the class that the lecturers use creatively. 16) Learner diversity refers to how lecturers build on learner differences in the classroom. 17) Course materials refers to how lecturers creatively include various differences in culture in their course materials or lesson plans. 18) Learner sharing refers to how lecturers creatively elicit experiences from the diverse learners to be shared in class. 19) Out of class teaching refers to how lecturers creatively use their time and resources to cater for individual learners’ needs outside class time. 20) Technology for assessment refers to the lecturers’ creative use of computer technology for assessment. 21) Flexibility in assessment refers to lecturers’ flexibility in allowing learners to creatively choose and complete assignments. 22) Open-mindedness in assessment refers to lecturer's consideration of all answers. Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 23) Assessment through play refers to assessment which is carried out through games and play. 24). Rewards in activities refer to how creative lecturers use rewards in an activity to motivate students with different motivational needs. 25) Needs-based activities refer to how lecturers creatively design activities that are suitable for learners’ strengths and weaknesses. 26) Challenging activities refer to how lecturers prepare creative activities which challenge different types of learners. 5.1 Themes From the axial codes and the re-analyses of the transcripts and open-codes, six common themes of how creative lecturers address equity and equality emerged. These were: 5.1.1 Resources Resources comprises the following axial codes (the numbers in parenthesis indicate the numbers given to the axial code above): Teaching aids (1), Access to resources (7), Audiovisuals (10), Technology (14) and Course materials (17). This theme encompasses teaching aids created for use during lectures and how they were made accessible so that learners with different preferences are given the freedom to choose these resources. Both Malaysian and Thai lecturers creatively used a variety of resources in their classes. For example, in addressing equity in the class, M3 used magic to teach learners who have difficulty in understanding concepts and M1, a Malaysian Physics lecturer at a private university, used the solar sail as an analogy to teach students who had difficulty in understanding ‘magnitude’. .. to teach magnitude you know, got calculations and all that… Just get them to understand… I show them a Star Wars video and talked about solar sail … the learners feel excited about learning. (M1, Interview) Similarly, a creative lecturer in Thailand, T2, used an onion as an analogy to explain the concept of love in her poetry class. I chose this poem “Onion” because the day we had this lesson was close to Valentine’s Day. I wanted to use a love theme. This poem was not too difficult, it showed two things that do not really go together. So, I think this created an opportunity to think. They had to think of what the two things represented and how could they go together. There was no right or wrong answer. It is up to imagination and interpretation. I wanted to show them that something different could be possible. We don’t have to look at it the way that other people do. (T2, Interview) This is similar to the common creative ideas generating technique called Forced Relationship or Forced Analogy, from Koestler’s bisociation approach (Koestler, 1964). Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 To address equality, creative lecturers choose or adapt teaching aids to suit all learners however diverse they may be. For example, a Thai lecturer described how she used worksheets, station games, pins, candies as well as little trumpets for the diverse learners including individuals with visual impairment. Thinking about how I came up with an activity…in this class, I knew the content I have to teach, what things my learners like, weakness, strengths. Learners were also from different years. Some were quiet. Two learners had visual impairments. I used materials that I can reuse or use for different purposes. (T2, Interview) Creative lecturers also provided access to resources through digital technology. For example, M10 used religious motivational videos in his classroom to address equity. Another lecturer, M5, allowed students to choose pictures and websites containing the designs of different cars currently in the market. These gave opportunities for different learners to explore various designs of their own interest which are relevant for the future. M5 gives examples for everything. He shows fascinating pictures. He always encourages us to access websites of automotive designers…automotive design because we’re taking that course now. He always says that you have to search for ideas…for things related to this subject and asks questions that we have to think on our own. (A focus group discussion) 5.1.2 Teaching Strategies This theme which encompasses the teaching strategies used to achieve lecture objectives includes the following axial codes: Teaching style (2), Material presentation (6), Teach to ability (13), Learner diversity (16), and Out of class teaching (19). The Malaysian and Thai lecturers used a variety of creative ways to address inequality and inequity in their classes. For example, a Malaysian lecturer addressed the needs of shy students as well as students with diverse academic abilities using a variety of strategies while a Thai lecturer designed strategies based on students’ learning styles. There are some shy students at the back...we have good students, average students and poor students. Good students, they will find the knowledge. The average students, almost 80% or 70% of them… if you help them a little bit, you can really help them. The poorest group needs more motivation…you give them some advice, encouragement, they will slowly change their attitude and look for more things themselves. (M3, Interview) Teachers have different teaching styles. These diverse pedagogies will make a difference to learners’ learning. Teachers have to think of how they can use pedagogy to positively impact learners’ learning who are different in styles and needs. (T2, Interview) Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 There were some who built on learner diversity by spontaneously using examples from countries where their learners originate to explain issues or subject matter. These findings were also triangulated by focus group learners. M1 will invite Korean learners to come in front and present their ideas…their points of view on things like policy [sic] they have in their countries. She just wants us to see a clear picture or comparison of what is happening in Korea and what is happening in Malaysia. She did it in creative way. (A focus group student) To capture the attention of students who find lectures uninteresting, M2 recounted his own experiences with his creative teachers. Similarly, some creative Thai lecturers like T4, narrated stories of their experiences. Because students must feel what they are learning is going to be implemented in their outside world, I will teach [what] will have an impact on their working life. I had once worked as an auditor, so I relate my lessons to my experiences with my working life. (M2, Interview) T4 helps us understand through her experiences. I like to be in her class because she always tells stories from her experiences. It wasn’t like studying in most classes where the lecturers sit and explain slides. (A focus group learner) To enhance student understanding of what future cars should look like, M5 got students to use the current models and modify them to design future cars. Similarly, a Thai lecturer used cartoons to help improve learners’ understanding of the subject matter. I believe that cartoons yield a variety of interpretation. [From] just one cartoon, people can see and interpret what it conveys to them differently. Some people may find a cartoon very funny, while others find that it is not. So, the learners were allowed to see the cartoons from their perspectives. The cartoons that I used have no cultural boundaries and the language was not difficult…some cartoons don’t even have written language but can imply so many ideas. (T2, Interview) Creative lecturers also used authentic activities in teaching English especially to those who are less proficient in the language. For example, a creative Thai lecturer, T2, got her learners to go to a shopping complex and interview English speaking foreigners. Actually in most classes she teaches, she brings so many activities. Sometimes I feel overwhelmed in a good way. But it was fun. Once we went to a shopping complex (Jamjuri Square) to interview foreigners in English. First I was embarrassed. Later, I found this a very fun thing to do. It is like once we have tried, the rest was getting easier and easier. (A focus group student) Another innovative strategy to help learners reflect on the lecture is to give incomplete notes as handouts for them to fill in and this motivated them to focus more on the lectures. Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 T3 always leaves blank parts for us to fill. I think if we get the handouts with everything in it, we might not pay much attention during the class. This way, we have to listen carefully and pay more attention. (A focus group student) Another creative strategy used by Malaysian lecturers to cater for learners of different abilities is to get students to discuss in groups to come up with answers. These answers were evaluated by other groups. M6’s class today is very interesting because actually we can see a lot of participation from the students and the interaction between us. (A focus group student) Some lecturers’ strategy was to allow students to make mistakes since they regard making mistakes as part of the learning and growing process. This was voiced out by students in their focus group discussions about their creative lecturer: Not to make a mistake is a mistake. So any teacher who gives you that comfortable room to make mistakes and to learn from mistakes is a great teacher … is a creative teacher. (A focus group student) 5.1.3 Assessment The Assessment theme refers to instances where lecturers creatively use various assessment methods to cater for different learner needs. Axial codes that represent this theme are: Assessment (3), Technology for assessment (20), Flexibility in Assessment (21), Open-mindedness in assessment (22), and Assessment through play (23). This involves the use of assessment methods that are fair to everyone. For example, M2, an engineering lecturer, used a self-created Random Matrix Number Selector to ensure all learners got an equal chance to answer his questions and be assessed. He points out: …when we want to select a student to write the solution, I select them randomly instead of picking the learners. … to make the teaching have more variation… to make it more interactive so that the learner will not feel bored …because I want to make the class different than the others (M2, Interview) Another lecturer assessed students’ assignments which were chosen by the students themselves. I don’t always tell them what I want. I want them to explore ….. (M1, Interview) This is further concurred by students in the focus group discussion: We can use whatever materials we want. So that’s what we like…she always gives us freedom…gives us a chance to find out ourselves how should we do it. Some lecturers considered both right and wrong answers. M6, for example, set challenging tasks and welcomed both answers: Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 You just throw them at the deep end of the pool. If you are right, great! If you are wrong, I’m here! Don’t worry. They are happy. (M6, Interview) Similarly the Thai lecturers also showed openness when assessing learners. What I did was I ask the whole class to answer different questions, if some of them gave wrong answers, nothing happens [it’s ok] … other people would then give more answers until someone gets the right one. I focus on “just speak out”. It can be right or wrong, that’s fine. They don’t have to feel bad for giving wrong answers. (T2, Interview) Some lecturers used creative assessment methods that appeal to some students. One example is the use of crossword puzzles for both learning and assessment. I used to make crossword quizzes. Although they learned about science, crosswords can help them remember vocabularies or concepts. I decided which words they need to know and selected them to put in each set of crossword. Then I provided them clues. I have both groups, having high and low scores. We always have to make changes to our teaching. (T4, Interview) 5.1.4 Language Language refers to the axial codes relating to Learner attitude (12), Tactfulness (9), Learner language (5), and Lecturer language (4). Creative lecturers use words that encourage and acknowledge learners’ ideas even if they are not aligned with theirs. They are also mindful of their classroom discourse to maintain equity. … we can’t kill the student’s idea, and say, “This is not right. And my idea is right. I – I don’t think I will do that….Some learners if you tell them this is wrong … that is wrong… they become less confident. (M1, Interview) Using friendly language to build cordial relationship with culturally diverse learners is one of the ways creative lecturers endear their students. This is common for both Malaysian and Thai creative lecturers. In the Thai context, friendly lecturers refer to themselves as “teacher” rather than “I” and the students as “learners” and not “you”. In one of the focus group discussions, this was mentioned about T4: This lecturer calls herself “teacher” and calls us “learners”, while some lecturers use “I” and “you” which create distant feeling between us. I am afraid to ask questions. (A focus group student) Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 In the Malaysian context, M8 switches from Malay to English and vice versa to cater for students who are linguistically diverse. And by the end of the class, we actually understood what she was trying to teach in her lesson today. And the second, I would say that she’s bilingual. Ok, no doubt that not all students can converse in English. So she talks a bit about the topic in English but she elaborates and explains in BM so that everyone may understand the subject. (A focus group student) Creative lecturers also use non-verbal language to be fair to all students in the class. To show that all students are important to her, one creative lecturer moves around the class. If I’m standing on one side, I might psychologically affect students on the other side who might think that I favor one group and I’m neglecting the others….. I must be seen to be a person of impartiality. (M8, Interview) Creative lecturers are also flexible in the classroom. Some allow students to use their preferred language for easy communication and better understanding. For example, students in the focus group mentioned that their lecturer, M7, allowed them to speak in Malay as well as in English as long as they are able to communicate well. Allowing learners to not only talk but also listen to others’ ideas is a creative pedagogical practice. This was highlighted in a focus group discussion. We learned to listen to other people’s ideas. Learned to find the best solutions among different ideas. The lecturer accepted our ideas… she has never said it is right or wrong. (T1, Focus group student) 5.1.5 Activities Activities refer to how lecturers creatively use resources to design activities which the students are free to choose. This is represented by these axial codes: Choice of activities (8), Rewards in activities (24), Needs based activities (25), and Challenging activities (26). In a focus group discussion one learner in M4’s class excitedly described her experience: I’m free to do anything I want…I can test out with my design with the... ‘Mentor Graphics’ software which is available in the Intel Microelectronics Lab. I can test out all the designs. I actually did around three to four models before I made the final one. (M4, Focus group student) In another focus group discussion from M10’s class, a learner described how other learners in her class were given the freedom to create materials according to their interests: Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 In his lab about dyes, for example. The lecturer said we can play around with dyes and colors … this is how people dye clothes. Yes there’s hair dye too. We also made lipstick, makeup and others. (A focus group student) Some lecturers also used rewards creatively in selected activities to motivate learners with different motivational needs. For example, a creative Thai lecturer who teaches English language used rewards creatively to make learning more interesting: Learners worked in group to collect points from 5-7 stations. In each station, the learners from different groups have to show how a sentence could be written in different styles. At the end, I told them that any station with red or pink color stuff will get 10 points. Others will get only 5 points. In some station, I put Mentos (candies) with red wrapping but the inside candies could be pink or other colors— if pink they get another 10 points! I believe that most people love surprises… without worrying about scores. (T2, Interview) To encourage learners who are not proficient in English to improve their language, T2 designed a journal activity which motivated them to put their thoughts down without constant evaluation. I also ask my learners to keep a free writing journal. I usually gave them broad and open topics such as compare 2 types of pets. I write feedback in the journal— something positive and encouraging. This is like a personal letter between the student and I. I will not grade the paper. They didn’t have to worry about grammatical errors. (T2, Interview) Some creative lecturers designed activities that are challenging to cater for the creatively inclined. For example, M6, who teaches poetry, got such students to role play by changing their middle names to someone they wanted to be: We choose a certain name, relate it with ourselves. It does not have to be exactly what we are and it can be the opposite. The one thing that we want to be but we can’t. So by having this middle name it gives us the chance [to act it out] to impress people. (M6, Interview) 5.1.6 Open-mindedness Open-mindedness comprises the axial codes that indicate Learner sharing (18), Interactions (11) and References (15). These are the hallmarks of a creative lecturer. Creative lecturers are open to incorporating ideas and experiences of diverse students to enrich their lessons. For example, a Malaysian creative lecturer used ideas from foreign student in his class: Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 .. last semester we had learners from Bangladesh, Nigeria, Korea and China. So I want them to feel part of my Malaysian economy [class]. I mean it’s good for our Malaysian students to know about other countries’ agriculture sector. I downloaded some articles and related to their countries to make policy comparisons. (M1, Interview) Creative lecturers were accommodative in their efforts to address equality: There is no right or no wrong [answers] … because we just look from different perspective. (M1, Interview) They are open to students’ ideas and believe in their creative potential. They also have high expectations of them: The education system always underestimates the learners. We worry the learners cannot do this and that. Actually the learners are more creative than us. …we need to learn from them indirectly, then we can produce better scholars. (M1, Interview) In summary, to address equality and equity, creative lecturers adapt a variety of resources such as magic, digital technology and relevant objects as analogies. They used a variety of teaching strategies, including group discussions and trial and error approaches. These strategies were chosen based on students’ learning styles, abilities, background and experiences. Authentic activities and incomplete notes were used to achieve learning objectives. Creative assessment methods included providing students with equal opportunities and allowing them to choose assessment methods. This included the creative use of crossword puzzles, and the consideration of all answers whether right or wrong. Creative lecturers communicate well to build rapport with their students. They are flexible in the language used and they move around the class to give equal attention to all students to motivate them. They also encourage students to listen to others’ ideas and allow them the freedom to choose activities and create materials. The lecturers design creative and challenging activities to improve students’ language proficiency. By being open-minded, these creative lecturers address diverse needs by believing in their students’ potential and incorporating their ideas and experiences. 5.2 Comparisons between Malaysian and Thai creative lecturers The above six themes were used to compare all the nominated creative lecturers from both countries to answer the second research question: Are there cultural differences in these areas of creative teaching between Malaysian and Thai creative lecturers? There were many similar as well as different ways in which Malaysian and Thai lecturers creatively ensured equality and equity. Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 5.2.1 Resources The Malaysian and Thai lecturers used different approaches when dealing with resources. For example, in the Thai classes, the shy learners were given practice sheets to answer questions on their own whereas the shy Malaysian students were asked to present scientific diagrams in front of the class and answer questions. Lecturers from both countries used questions from students as resources. However, the Malaysian lecturers let students brainstorm answers to their own questions while the Thai lecturers provided more guided discussions of such questions. Another similarity between the two is that both used teaching aids to make learners think but the Malaysian lecturers used a variety of resources such as video, brain-twisters, talks by experts, visual aids and seminars. 5.2.2 Teaching strategies Creative lecturers in both countries used experiences to emphasize certain points. The Malaysian lecturers used their students’ background information to emphasize certain points while the Thai lecturers used their own experiences. For example, M1 used examples from students’ home countries to compare and contrast their countries’ economic policies while T4 selected pictures taken from her stay in Japan to enhance student understanding. The Malaysian lecturers used senior students’ work as prompts for new ideas whereas the Thai lecturers generated new ideas from their students. Both lecturers addressed equity by using different approaches for different learners. For example, the Malaysian lecturers used group work for weak learners and individual work for the competent ones whereas the Thai lecturers helped the weaker ones by giving examples but allowed the good students to think on their own. The Thai lecturers tend to give reading assignments for class discussio. However this is not frequently used among Malaysian creative lecturers. Given the demand for English proficiency, creative lecturers from both countries used a variety of methods. For example, the Thai lecturers got learners to interview foreigners at shopping complexes. Similarly, the Malaysian lecturers encouraged learners to read English journal articles to improve their proficiency. The lecturers also used creative ways to select learners to answer questions. While a Thai lecturer tossed models of molecules for the students to catch and answer questions, a Malaysian lecturer used a random number selection program for the same purpose. 5.2.3 Assessment Malaysian and Thai lecturers catered for bright and weak learners by considering both right and wrong answers through a variety of assessment approaches. For example, Malaysian lecturers used Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 student presentations, discussions, group assignments and lab based creations whereas the Thai lecturers used crossword puzzles and cloze tests. 5.2.4 Language Both Malaysian and Thai creative lecturers engaged in friendly communications with their students to ensure fairness and openness. They also used words of endearment. However, there are differences in their usage. In the Malaysian setting, the lecturers used terms like “dear”, “darling” and “hang” (which meant ‘you’ in Northern states of Malaysia) but did not allow students to call them by their nicknames. In contrast, the Thai lecturers and students address each other by nicknames. Another difference between the two countries is a cultural one. In the Malaysian linguistically diverse student population, lecturers allowed students to use both Malay and English, whereas the Thai students, being monolinguals, used mostly Thai. 5.2.5 Activities Both Malaysian and Thai lecturers promoted student autonomy by encouraging students to choose their own activities. For example, M10 allowed students to create products of their choice in the lab while, T2 allowed students to choose activities that they found most comfortable for their English classes. 5.2.6 Open-mindedness Malaysian and Thai lecturers are open-minded when incorporating examples in the class. However, they do this differently. The Malaysian lecturers showed open-mindedness by using examples from international students but the Thais did this by considering different ideas springing from classroom debates and discussions. In summary, although Malaysian and Thai creative lecturers used similar creative strategies to address equality and equity issues, the approaches they used to execute these strategies were different. 6 Discussion Almost all institutions face equality and equity issues which arise from cultural, socio-economic, gender, linguistic and other individual differences. Resolving these issues requires much effort and creativity especially in institutions of higher learning where internationalization of education has resulted in increased student diversity. Scarce resources (Reed & Oppong, 2005) and time constraints compound efforts aimed at addressing these issues (Lilly & Bramwell-Rejskind, 2002). Hence, instructors need creativity in resolving these issues. Our investigation studied creative lecturers in Malaysia (a multiracial country) and Thailand (an almost homogeneous society) with Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 the hope of advancing current knowledge in addressing equity and equality issues in institutions of higher learning. This is the first study using multiple data sources to triangulate findings in investigating how creative teachers in two different countries addressed equality and equity issues in higher education. The six themes of creative teaching for equality and equity reflected some of the components of the creative teaching framework reported by Palaniappan (2008) which was derived from the four dimensions of Rhodes’s (1961) classification of creativity as Process, Person, Product and Press. The themes Resources and Activities may be considered as the Product. Teaching strategy, Language and Assessment reflect the Process while Open-mindedness provides support for the Person dimension of the creative teaching framework. However, the findings offered very little support for the Press dimension indicating that universities do not provide a very conducive environment for creative lecturers to address diversity issues. The themes Resources and Assessment also reflect Reid and Petocz’s (2004, p. 45) conceptualization of creative teaching as involving the use of “appropriate materials and assessment techniques”. To address equality and equity in a diverse classroom environment, lecturers may need to first understand the nature of diversity among their students and what appeals to most of them. Based on the findings of this study, it appears that lecturers are able to cater for student needs by adapting resources such as videos, games and puzzles to suit student diversity (Sawyer, 2004; Scarino, & Liddicoat, 2009). The comparison between Malaysian and Thai lecturers revealed that this is more crucial in a heterogeneous classroom like those in Malaysia than the almost homogeneous one in Thailand. As for teaching strategies, the findings also show that creative lecturers resort to multi-modal strategies (Grainger & Barnes, 2006), by incorporating analogies, videos and class discussions into authentic cultural experiences. Discussions involving students’ own multicultural experiences tend to benefit culturally and linguistically diverse students (Stritikus & Varghese, 2010). This tends to cater for creative students who are easily bored by the traditional teaching methods. Both Malaysian and Thai creative lecturers address student cultural and linguistic diversity by providing opportunities for hands-on practice which also enhance learning. Flexibility in assessment (Rinkevich, 2011) has been found to address the need to allow students with diverse abilities to show their strengths and creativity in their presentations. This motivates the students to complete their work and enhances their conceptual understanding. Assessment can also be used to encourage interest, commitment, intellectual challenge (Ramsden, 2003) and create something new (Tanggaard, 2011). The use of a variety of assessment approaches seems to cut across culture. Language was found to play an important part in reflecting the lecturer’s attitude towards equality and equity. Creative lecturers have a natural predisposition for creating friendly and close relationships with their students. This reduces the “social gap” between lecturers and students. One way they seem to achieve this is via terms of endearment (Eggins, 2004). Creative lecturers tend to simplify the language to cater for students with varying levels of language proficiency (Rix, 2006; You & You, 2013). They are linguistically fluent and are able to Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 communicate in different languages in multilingual classrooms. This enhances some aspects of student creativity, namely, flexibility and fluency (McLeay, 2004). Activities form an integral part of creative teaching as they involve creativity in the planning and designing process (Cornish, 2007; Gibson, 2010). These activities, in turn, enhance student creativity (Rejskind, 2000; Simplicio, 2000) as they involve, among other things, empowering students to choose their own activities (Gibson, 2010). Creative lecturers have one dominant personality characteristic which is open-mindedness (Gibson, 2010; Grainger et al., 2004). They are open to students’ ideas and also encourage students to listen to other students’ ideas which are crucial in brain-storming creative solutions to problems. Hence, open-minded lecturers not only enhance equality and equity in the classroom but also students’ creativity. This is more evident in the multicultural context than in the monolingual ones. All the six themes appear to be necessary in order for lecturers to creatively address equality and equity issues. Adapting resources to needs of individual students (equity) and designing activities that consider student diversity are made possible when lecturers are open-minded and willing to diversify teaching strategies. Friendly and interactive lecturer-student communications where lecturers monitor both their language as well as students’ language for bias and prejudice are crucial for inclusive education. 7 Limitations and Recommendations The findings of this study need to be interpreted in light of various limitations. Firstly, the creative lecturers from Malaysia were chosen only from one private and two government universities in Kuala Lumpur and the state of Selangor, while those from Thailand were only chosen from two faculties from a prominent government university. Hence, the findings of the study may not be generalizable to all creative lecturers in Malaysia and Thailand. Secondly, while we were able to get informed consent from twelve creative Malaysian lecturers, we were only able to get similar consent from only four Thai creative lecturers. Thirdly, in one of the faculties in Malaysia and one in Thailand, the lecturer who obtained the highest student nomination declined to take part in this study. Consequently, those with the second highest nominations were invited to participate in the study. Fourthly, the unavoidable lapse in time between nomination of lecturers and their subsequent class observations did not allow the researchers to observe these lecturers teaching the subject they were nominated for. Future research may involve a more representative sample of creative lecturers from each country. Observing creative lecturers teaching subjects they were nominated for would provide a better assessment of their creative teaching abilities. Exploring the reasons for the differences between the two countries would also extend the findings of this research. 8 Conclusion Findings from this study indicate that there are six main areas where Malaysian and Thai creative lecturers addressed equality and equity. These are Resources, Teaching strategies, Assessment, Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 Language, Activities and Open-mindedness. Creative teachers are able to creatively design or adapt resources and activities which the diverse students are free to choose according to their needs. They have a repertoire of teaching strategies to match with students’ learning styles. They employ culturally responsive communication styles. Being open-minded, they allow a range of assessment approaches that cater to the needs of their diverse students. Although Malaysian and Thai creative lecturers addressed equality and equity issues in similar areas, the approaches they used to execute these creative strategies appear to differ. These findings have implications for teacher training programs, curriculum planners and policy decisions across cultures aimed at enhancing teachers’ ability to address equality and equity issues creatively. References Ambrose, D. (2005). Creativity in teaching: Essential knowledge, skills, and dispositions. In J. Kaufman, & J. Baer (Eds.), Creativity across domains (pp. 281-298). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Achinstein, B., & Athanases, S. Z. (2005). Focusing new teachers on diversity and equity: Toward a knowledge base for mentors. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21, 843 – 862. Awang, H., & Ramly, I. (2008). Creative thinking skill approach through problem-based learning: Pedagogy and practice in the Engineering classroom, International Journal of Human and Social Sciences, 3(1), 18- 23. Beghetto, R. A. (2007). Does creativity have a place in classroom discussions? Prospective teachers’ response preferences. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 2, 1-9. Blanchet-Cohen, N., & Reilly, R. C. (2013). Teachers’ perspectives on environmental education in multicultural contexts: Towards culturally-responsive environment education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 36, 12-22. Brown, M. R. (2007). Educating all students: Creating culturally responsive teachers, classroom, and schools. Intervention in School and Clinic, 43(1), 57-62. Chan, D. W., & Chan, L. K. (1999). Implicit theories of creativity: Teachers’ perception of student characteristics in Hong Kong. Creativity Research Journal, 12(3), 185-195. Cheng, M. Y. (2004). Progress from traditional to creativity education in Chinese societies. In S. Lau, A. N. N. Hui, & G. Y. C. Ng (Eds.), Creativity: When East meets West (pp. 137–167). Singapore: World Scientific Publishing. Cheng, M. Y. (2011). Infusing creativity into eastern classrooms: Evaluations from student perspectives. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 6, 67-87. Clouder, L., Oliver, M., & Tait, J. (2008). Embedding CETLs in a performance oriented culture in higher education: reflections on finding creative space. British Educational Research Journal, 34(5), 635–650. Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 Cooley, M. L. (2007). Teaching kids with mental health and learning disorders in the regular classroom: How to recognize, understand, and help challenged and challenging students succeed. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit Publishing. Cornish, L. (2007). Creative teaching: Effective learning in higher education. Paper presented at 32nd international conference on improving university teaching: The creative campus, July 4-7, in Jaen, Spain. Costa, A. L., & Kallick, B. (2009). Habits of mind across the curriculum: Practical and creative strategies for teachers. Alexandria, VA.: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Daniels, S. (2013). Facilitating creativity in the classroom: Professional development for K12 teachers. In M. B. Gregerson, H. T. Snyder, & J. C. Kaufman (Eds.), Teaching creatively and teaching creativity (pp. 3 -14). New York: Springer. Davis, D., Jindal-Snape, D., Digby, R., Howe, A., Collier, C., & Hay, P. (2014). The roles and development needs of teachers to promote creativity: A systematic review of literature. Teaching and Teacher Education, 41, 34-41. DeHaan, R. L. (2009). Teaching creativity and inventive problem solving in science. CBE – Life Sciences Education, 8, 172-181. Derounian, J. (2011). Fanning the flames of non-conformity. Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education, 3, 1-6. Eason, R., Giannangelo, D. M., & Franceschini III, L. A. (2009). A look at creativity in public and private schools. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 4, 130-137. Eggins, S. (2004). An introduction to systemic functional linguistic. London: Continuum. Gay, G. (2000). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. New York: Teachers College Press. Gibson. R. (2010). The ‘art’ of creative teaching: Implications for higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 15(5), 607-613. Glaser, B. G., & Stauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of Grounded Theory. Chicago, IL: Aldine. Grainger, T., & Barnes, J. (2006). Creativity in the primary curriculum. In J. Arthur, T. Grainger, Teresa, & D. Wray, (Eds.), Learning to teach in the primary school. (pp. 209 - 225). London, UK: Routledge. Grainger, T., Barnes, J., & Scoffham, S. (2004). A creative cocktail: Creative teaching in initial teacher education. Journal of Education for Teaching: International Research and Pedagogy, 30(3), 243–253. Hazri, J., & Raman, S. R. (2012). Malaysian educational policy for national integration: Contested terrain of multiple aspirations in a multicultural nation. Journal of Language and Culture, Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 3(1), 20-31. Horng, J. S., Hong, J. C., ChanLin, L. J., Chang, S. H., & Chu, H. C. (2005). Creative teachers and creative teaching strategies. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 29(4), 352– 358. Jeffrey, B. (2006). Creative teaching and learning: Towards a common discourse and practice. Cambridge Journal of Education, 36(3), 399–414. Kangas, M. (2010). Creative and playful learning: Learning through game co-creation and games in a playful learning environment. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 5, 1 – 15. Koestler, A. (1964). The act of creation. New York, NY: Macmillan. Levin, B. (2003). Approaches to equity in policy for lifelong learning, equity in education. Winnipeg, Canada: Education and Training Policy Division, (OECD). Lilly, F. R., & Bramwell-Rejskind, G. (2004). The dynamics of creative teaching. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 38(2), 102-124. Lincoln, Y., & Guba, E. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Lou, S., Chen, N., Tsai, H., Tseng, K., & Shih, R. (2012). Using blended creative teaching: Improving a teacher education course on designing materials for young children. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 28(5), 776-792. McLeay, H. (2004). The relationship between bilingualism and the performance of spatial tasks. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 6(6), 423–438. Ministry of Education. (2012). National educational blueprint (2013-2025). Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Educational Planning and Research Unit. Misawa, M. (2010). Queer race pedagogy for educators in higher education: Dealing with power dynamics and positionality of LGBTQ learners of color. International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 3(1), 26-35. Mohd Roslan Mohd Nor. (2011). Religious tolerance in Malaysia: An overview. Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research, 9 (1), 23-27. Munro, J. (2012). Effective strategies for implementing differentiated instruction, School Improvement: What does research tell us about effective strategies? Conference Proceedings Australian Council of Educational Research, 48. National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education. (1999). All our futures. London: DfEE. National Office for Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities (NEP). (2007). Persons with Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 Disabilities Empowerment Act B.E. 2550. Bangkok: Thai Ministry of Human Development and Social Security. Palaniappan, A. K. (1996). A cross-cultural study of creative perceptions. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 82, 96-98. Palaniappan, A. K. (2008). Creativity research in Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur: Scholar Press. Paul-Binyamin, I., & Reingold, R. (2013). Multiculturalism in teacher education institutes: The relationship between formulated official policies and grassroots initiatives. Teacher and Teacher Education, 42, 47-57. Pope, R. (2005). Creativity: Theory, history, practice. Oxon: Routledge. Prentice, R. (2000). Creativity: A reaffirmation of its place in early childhood education. The Curriculum Journal, 11(2), 145-158. Public Policy Institute. (2011). Equity and education. Melbourne: Australian Catholic University. Ramsden, P. (2003). Learning to teach in higher education. New York, NY: RoutledgeFalmer. Rasulzada, F., & Dackert, I. (2009) Organizational creativity and innovation in relation to psychological well-being and organizational factors. Creativity Research Journal, 21(2-3), 191-198. Reed, J. R., & Oppong, N. (2005). Looking critically at teachers’ attention to equity in their classrooms. The Mathematics Educator, 1, 2-15. Reid, A., & Petocz, P. (2004) Learning domains and the process of creativity. The Australian Educational Researcher, 31(2), 45-62. Reilly, R. C., Lilly, F., Bramwell, G., & Kronish, N. (2011). A synthesis of research concerning creative teachers in a Canadian context. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(3), 533-542. Rejskind, F. G. (2000). TAG teachers: Only the creative need apply. Roeper Review, 22, 153-157. Rhodes, M. (1961). An analysis of creativity. Phi Delta Kapan, 42, 305 - 310. Rinkevich, J. L. (2011). Creative teaching: Why it Matters and Where to Begin, The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 84(5), 219-223. Rix, J. (2006). Simplified language materials: Their usage and value to teachers and support staff in mainstream settings. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22, 1145-1156. Sawyer, R. K. (2004). Creative teaching: Improvisation in the constructivist classroom. Educational Researcher, 33(2), 12-20. Scarino, A., & Liddicoat, A. J. (2009). Teaching and learning languages: A guide. Report prepared for Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. Australia: Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015 Carlton South Vic: Curriculum Corporation. Simplicio, J. S. C. (2000). Teaching classroom educators how to be more effective and creative teachers. Education, 120(4), 675-680. Sousa, F. C. (2007). Teachers’ creativity and effectiveness in higher education: Perceptions of students and faculty. The Quality of Higher Education, 4, 21-37. Stritikus, T. T., & Varghese, M. M. (2010). Language diversity and schooling. In J. A. Banks & C. A. M. Banks (Eds.), Multicultural education: Issues and perspectives (7th ed.) (pp. 297325). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. Tanggard, L. (2011). Stories about creative teaching and productive learning. European Journal of Teacher Education, 34(2), 219-232. Torrance, E. P. (1990). Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking: Norms-technical Manual. Bensenville, IL: Scholastic Testing Service. (Originally published by Personnel Press, 1966). Westby, E. L., & Dawson, W. L. (1995). Creativity: Asset or burden in the classroom? Creativity Research Journal, 8(1), 1 – 10. Wiseman, A. W. (2008). A culture of (in)equality?: A cross-national study of gender parity and gender segregation in national school systems. Research in Comparative and International Education, 3(2), 179-201. Woods, P., & Jeffrey, B. (1996). Teachable moments. Philadelphia, PA: Open University Press. Yewchuk, C. (1998). Learning characteristics of gifted learners: Implication for instruction and guidance. The New Zealand Journal of Gifted Education. Retrieved on June 16, 2014: http://www.giftedchildren.org.nz/apex/v12art06.php. You, X., & You, X. (2013). American content teachers’ literacy brokerage in multilingual university classrooms. Journal of Second Language Writing, 22, 260-276. Paper presented at the 3RD ANNUAL CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATION 2015 in CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, USA 25-26 May 2015