European Parliament Magasine DRAFT article

advertisement

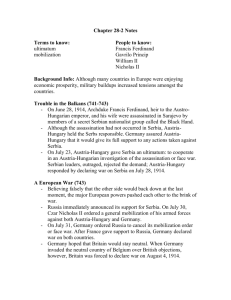

Tough challenges ahead for Serbia The recent political standoff between Croatia and Serbia – which was proof that the legacy of the war is still very much alive in the Western Balkans – came to a welcome end last month: the long delayed meeting between Serbian and Croatian Prime Ministers took place in Belgrade on 16 January. Croatia's entry into the fold of the EU, which is envisaged for 1 July 2013, will be the D day for all other Balkan countries - and in particular Serbia. Serbian Prime Minister Ivica Dačić, who was elected in July 2012, inherited a minefield of challenges from his predecessors. These include, of course, Kosovo. But they also include the legacy of Slobodan Milošević's rule and a business environment which has so far privileged a few and punished those who were not ‘part of the club’. Years of isolation and political oppression under Milošević – which left state institutions in ruins while private interests and organized crime called the shots - left a permanent scar on the independence of Serbia’s judicial and prosecution services and their abuse by the executive branch of the government. Botched reforms of the judiciary launched in 2008 by the previous administration didn’t help. The European Parliament’s Delegation for relations with South East Europe has, in the last few years, been informed of a number of cases of Serb and EU business people being jailed for months – often after they had bought state companies during Serbia’s privatization process - under suspicion of ‘abuse of office’. This Serbian Criminal Code offense applied as much to people working in the private sector as the public one, and was selectively misused by former administrations as a ‘catch all’ tool to punish those who had fallen out of favour. Lawyers nicknamed this practice "state racketeering". These cases dealt a heavy blow not only to the already shaky public trust in the rule of law in Serbia, but also to its economy: state seizures of privatized companies, and the detention of their owners, lead to hundreds of worker lay-offs. Stories such as these are, of course, a damning indictment on Serbia’s privatization and judicial frameworks as well as its human rights track record. DG Enlargement’s renewed emphasis on rule of law is therefore warmly welcomed. But, for a country which hopes to boost foreign direct investment, these stories are also a huge red flag to those legitimate investors who might have otherwise have considered investing in Serbia. The new Serbian government, conscious of these challenges, appears to have been moving in the right direction. Under the leadership of Deputy Prime Minister Aleksandar Vučić, it has taken a tougher stance on corruption, proposed legislation aimed at restoring the independence of Serbia’s judiciary and partially reformed its antiquated criminal code. The popularity of Mr Vučić', who is also the leader of the largest ruling party SNS, has skyrocketed since his anti-corruption campaign was launched. But Serbia still has a long way to go: for it to be taken seriously as a credible place to do business the government needs to create a level playing field for all investors, which can only be guaranteed by competent, independent and accountable state institutions. All this is, of course, no easy feat. Which is why I call on my colleagues in the European Parliament to lend Serbia as much support as necessary to ensure that it becomes the modern and prosperous country Serbs deserve.