DEATH

advertisement

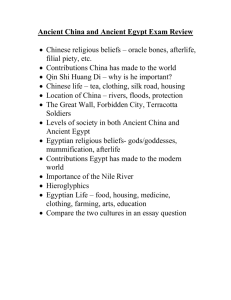

CONTEXTUALIZING DEATH Sonya Merrill, MD, PhD Presbyterian Hospital of Dallas January 27, 2004 OUTLINE DEATH IN THE CONTEXT OF: Two Ancient Cultures Four Major World Religions Modern Medicine Society: Nationality, Ethnicity and Class The Individual Ancient Cultures Egypt Mesopotamia ANCIENT EGYPT General Principles Preoccupation with life and desire to “continue living” after death Belief that Afterlife would resemble but improve upon earthly life Importance of continuing bodily existence (e.g., mummification, attempts to recover bodies, fear of being eaten by animals) “Ideal” life span: 100 years ANCIENT EGYPT The Soul Ba: the soul which animates the body, usually represented as a bird flying away at the time of death Akh: the spirit which also survives death and which can be good or evil, equipped with “spells” that would be useful after death Ka: difficult to conceptualize but often represented by a person’s image or statue and thought to be a “protecting genius” after death Suyt: a person’s shadow ANCIENT EGYPT The Body and its Preservation Mummification: removal of the decay-prone viscera enabling preservation of the majority of the body parts; process lasting 30-200 days Step 1: Removal of entrails through left-sided thoracic incision and storage in canopic jars bearing images of the sons of the god, Horus Liver (human son, Imesty) Lungs (ape son, Hapy) Stomach (jackal son, Duamutef) Intestines (hawk son, Qebekhsenuef) ANCIENT EGYPT The Body and Its Preservation Step 2: Removal of other organs Heart: “seat of intelligence” so after removal was wrapped in linen and replaced/sewn into chest cavity Brain: not always removed as not deemed very important; when removed, long hooked rods inserted into nostrils to snag tissue Step 3: Application of the natron, a natural desiccant Step 4: Complete drainage of all bodily fluids Step 5: Careful wrapping of the body in hundreds of yards of linen ANCIENT EGYPT The Body and Its Burial The Opening of the Mouth ceremony: eyes, ears, nostrils and mouth touched to symbolize opening and person’s revival Tombs: contained biographical information to preserve occupant’s name, reputation; varied according to importance of deceased VIP burial arrangements: Old Kingdom: wooden coffin inside stone sarcophagus Middle Kingdom: human-shaped wooden coffin with mask over mummy’s head inside stone sarcophagus New Kingdom: elaborately painted anthropoid nested coffins, e.g., Tutankhamun’s 3 nested coffins ANCIENT EGYPT Afterlife: The Rough Guide How to get there: Funerary texts: provided deceased with all necessary information to navigate the afterlife By boat: sailing on day-night journey with the Sun God attainable using basic spells which were left in guidebooks near the body Where to go when you arrive: Field of Offerings: land in the western horizon where deceased would work in lush fields and orchards to produce offerings for the god Osiris Paradise: deceased reaps the fruits of his own labor and enjoys a blissful existence ANCIENT EGYPT Afterlife: The Rough Guide What to pack: Premise: deceased require basic provisions to survive in the afterlife Initially, basic provisions such as bread, beer, meat, wine, linens were placed in tomb Later, models of provisions were deposited to guarantee that supplies would last Who to bring with you: Models of servants responsible for provisions were included so that they could continue to produce necessary supplies forever ANCIENT EGYPT Conclusions Optimistic belief that all bodily and spiritual aspects of person survived in afterlife Great effort to ensure that deceased not only survived but thrived in afterlife: Mummification Opening of the Mouth ceremony Elaborate burials with provisions Guide books to the afterlife Spells to ensure deceased’s safety ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA General Principles Death is inevitable: “when the gods created men, they set aside death for mankind and kept eternal life in their own hands” Use of euphemisms: speaking of death summoned it, so “to die” was: “to cross the Khubur,” “to go up to heaven,” “to go to one’s fate,” “to be invited by one’s gods,” “to come to land on one’s mountain,” “to go on the road of one’s forefathers” A gradual process rather than an instantaneous end of earthly existence: The individual corpse The individual ancestor dependent on descendents’ offerings After several generations, collective ancestral spirits Finally, annihilation of individual and recycling into new soul ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA The Soul Etemmu: ghost closely associated with physical remains Napistu: life force or “breath of life” Zaqiqu: birdlike spirit able to fly and slip through small spaces, associated with dreaming as it could leave body when person was asleep; closest to modern equivalent of soul Both etemmu and zaqiqu descended with the body to the netherworld at death; if the body had been destroyed, then etemmu was also destroyed leaving only shadowy zaqiqu which was deemed harmless ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA The Body and Its Burial Preparation of body: ceremonial washing, tying the mouth shut, perfuming, dressing in clean clothes Public viewing: before the funeral Burial: in the ground in a coffin, sarcophagus or tomb Elite buried in vaults below their house or palace while others buried in public cemeteries Last rite: a burnt offering, which in the case of the king consisted of burning his throne, table, weapon and scepter ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA Funeral Customs Mourning rituals could last up to 7 days Family and close friends were expected to participate; in the case of the death of royalty, the entire population had to mourn Professional mourners sometimes employed Funeral laments expressed mourners’ grief and eulogized the deceased Physical displays of grief: wearing plain clothes, tearing clothes, wearing sackcloth, not bathing or grooming, fasting ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA Afterlife: The Rough Guide How to pack: take as many personal items as you can afford Travel provisions for the journey: food and sandals (or a chariot, if you were wealthy) Things you might need when you arrive: food, weapons, toiletries, jewelry Hostess gifts: to placate the netherworld gods ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA Afterlife: The Rough Guide Where: underground Climate: a rather dark, damp and dreary place How to get there: cross demon-infested lands, pass the Khubur River with the aid of its guardian god, gain entry through 7 gates to the city of the netherworld with its gatekeeper’s permission Your hosts: the royal couple, Nergal and Ereshkigal, and their court; they welcome the dead, instruct them as to the local rules, and show them to their lodgings in the netherworld (which did not appear to be based on the deceased’s earthly behavior) ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA Afterlife: The Rough Guide How to be happy there: your happiness after death depended on the quality and quantity of offerings made to you by your relatives; offerings had to be made continually to ensure continued success in the afterlife How to have an awful time: without offerings, or if your death had been violent or premature, you’d be restless and your ghost would wander the earth attacking people Multiple-entry visas: the deceased generally received offerings from behind the gates of the netherworld but were allowed “out” (and back in) several times a year to visit relatives (e.g., the month of Abu = July/August) Recycling policies: eventually old souls were recycled into new human beings ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA Conclusions Some sort of ghostly existence after death which was accessed only via burial and mourning rituals No bodily resurrection or judgment The ideal death: surrounded by family and friends while lying on the special funerary bed with a chair at one’s left which served as the seat for the soul after its release from the body Four Major World Religions Judaism Christianity Islam Hinduism JUDAISM The Origin of Death “God saw all that he had made, and it was very good” Gen 1.31 The first humans disobey God Gen 3 Death introduced to the world as a consequence of human disobedience: “for dust you are and to dust you will return” Gen 3.19 Being bene Adam (sons of Adam) makes all future people subject to the penalty of death Thus death is an inevitable and feared event JUDAISM What happens when we die? Death occurs when rwh, the divine life-giving force, leaves the body; rwh distinguishes the living from the dead JUDAISM What happens after we die? At death, the body returns to dust, and the breath which God breathed into it initially (rwh) returns to the air, or to God: nothing can survive God makes his covenant (promises) with the Jews regarding their future on earth (e.g., the continuity of the nation and of one’s descendents), not with regard to an individual’s survival after death Thus death is acceptable only at the end of a long life when one has descendants who can preserve one’s memory JUDAISM What happens after we die? Sheol as a metaphor for death: a ghostly, subterranean land of the dead an inferior copy of life on earth not necessarily hell (i.e., a place of torment), but certainly a place to avoid for as long as possible chiefly because it entails permanent separation from God – even for the righteous Sheol “The days of my life are few enough: turn your eyes away, leave me a little joy, before I go to the place of no return, the land of murk and deep shadow, where dimness and disorder hold sway, and light itself is like the dead of night.” Job 10.18-22 JUDAISM What happens after we die? The possibility of an afterlife If God has been the Jew’s creator (in the past) and guardian (in the present), why not his sustainer (in the future)? During the Babylonian exile, there was an emphasis on the future restoration of Israel to peace and prosperity by the Messiah And if those Jews alive at this future time could be restored, why couldn’t the faithful dead also experience a restoration to life (return of blood and breath)? Hope of an individual’s life after death became widespread by the Rabbinic period: Maimonides said that anyone who doesn’t believe in the resurrection of the dead is not a true Jew JUDAISM What happens after we die? “O my God, the soul which you gave me is pure: you created it, you formed it, you breathed it into me, you preserve it within me; and you will take it from me. But you will restore it to me in the hereafter.” Authorized Daily Prayer Book p. 5 JUDAISM What happens after we die? Transmigration: According to the Kabbalah, souls can go from one body to another (gilgul, or transmigration): those deserving punishment or those who are extremely righteous JUDAISM How is death observed? Be present at the time of death/departure of the soul Recite at least the last part of the Shema at the moment of death Accompany the body to the grave Funeral lamentations in the presence of the corpse Burial of the corpse (and in ancient times, preservation of the bones in an ossuary) Shivah: week-long period of mourning – in ancient times sprinkling of ashes, rolling on the ground, tearing clothes, dressing in sackcloth; in modern times, forsaking one’s everyday work and routine Kaddish: to be said at the Yahrzeit (first anniversary of death) CHRISTIANITY The Origin of Death Shared with Judaism (and later with Islam) “Original sin” of the first humans brought the penalty of death not only to Adam and Eve but to all people CHRISTIANITY The most important death… The crucifixion of Jesus a common means of execution of criminals in the Roman Empire “…the soldiers took charge of Jesus. Carrying his own cross, he went out to the place of the Skull (which in Aramaic is called Golgotha). Here they crucified him….” John 19.16-18 CHRISTIANITY …because it ends all Death Centrality of the death and resurrection of Jesus Based on people’s eye-witness accounts of his death and resurrection as well as on his teachings, the Christian doctrine of resurrection was formulated “For as by man came death, by a man has come also the resurrection of the dead. For as in Adam all die, so also in Christ shall all be made alive.” I Cor 15.21-22 “…our Savior Jesus Christ ...destroyed death and has brought life and immortality…” 2 Tim 1.10 “Death is swallowed up in victory: O Death, where is thy sting? O grave, where is thy victory?” Hosea 13.14/1 Cor 15.54-55 CHRISTIANITY What happens after we die? The Afterlife Destination determined by the individual’s acceptance or rejection of the salvific death and resurrection of Jesus Heaven Eternal life for the believer in a “perfected” body Life in the continual presence of God Absence of death, pain, grief, war, conflict Metaphors of “streets of gold”, etc. Hell Separation from God Limited period (annihilationism) or eternal punishment Metaphors of “lakes of fire and brimstone” CHRISTIANITY How is death observed? During life: through the Sacraments Baptism: “we were buried with him [Christ] through baptism into death in order that, just as Christ was raised from the dead through the glory of the Father, we too may live a new life [on earth and in the afterlife].” Rom 6.4 Eucharist: “whenever you eat this bread and drink this cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes.” 1 Cor 11.26 CHRISTIANITY How is death observed? At and after death: Last rites: “into thy hands, Merciful Savior, we commend the soul of thy servant, now departed from the body … receive him into the arms of thy mercy…”The Book of Common Prayer Christian burial Requiem mass Prayers for the dead ISLAM The origin and purpose of death The origin of death: as in Judaism and Christianity The will of God: the original sin of Adam and Eve, and the punishment: “In the earth you will live, and in it you will die …” Quran 7.24 “It is not possible for a soul to die except with the permission of God at a term set down on record.” Quran 3.139 A time of trial: Life is a time of probation and decision: while alive, individuals are free to direct their lives along the straight path back to God (sirat ulMustaqim) or to reject God Quran 1.5 ISLAM What happens when we die? Human beings are body and spirit: separated, then reunited Bashar: “flesh”, the body Ruh: God’s “breath” or soul with which he infuses the bashar and which continues to live apart from the body after death until its reunion with the body on the Day of Resurrection Nafs: the “spiritual vitality” linking body and soul, which escapes at the time of death (and also departs the body at night in sleep and returns in the morning) Quran 6.60f ISLAM What happens after we die? The angel of death gathers those who are due to die Quran 32.10/9-11 The body is buried and decays The soul escapes the body and may either be raised into an interim body or be in a suspended state The body and soul are reunited on the Day of Resurrection (yaum ulQiyama): “…we will raise him up on the day of resurrection…”Quran 20.125 The appearance before God on the Day of Judgment (yaum udDin) ISLAM Judgment and the Afterlife Day of Judgment: “on the Day of Resurrection we will bring out a written record: each man will see it spread open” Quran 17.14 No one can “redeem” or “atone” for the misdeeds of another (contra Christianity) The Garden of Reward: for the ones who turn to God during life (eternal pleasure) The Fire of Jahannam: for those who reject God during life (eternal burning with fire) ISLAM How is death observed? Washing and burying the body within 8 hours of death Respect for the body (because it will be restored on the Day of Resurrection) Prayers over the dead (the four takbirs: proclamations of God’s greatness) Recitation of the whole Quran if possible Mourning should not be excessive, as this would disturb the dead as well as show lack of acceptance of God’s will and purpose regarding death HINDUISM Traversing a continuum “Hinduism is the map of how to live appropriately … in order to move towards (and perhaps attain) the goal.” J Bowker, The Meanings of Death. Cambridge: CUP, p. 131. HINDUISM The soul is eternal Souls are eternal and do not die with the body: as Krishna said, “Those who are truly wise do not mourn for the dead any more than they do for the living. … Just as embodied selves pass through childhood, youth and old age in their bodies, so too there is a passing [at death] to another body.” Bhagavad Gita 2.12 To attain this condition of wisdom about the soul’s eternality is to attain brahman HINDUISM The goal is to free the self Brahman/nirvana: the freed self who has attained a state of wisdom regarding the eternality of the soul A state of power experienced both in this life and after death Liberation achieved by renouncing all desired objects and not experiencing any cravings for them, absence of preoccupation with the bodily self Gita 2.71f The state of happiness and peace from being eternally with Krishna (and yet distinct from him) HINDUISM The cycle of death and rebirth The self is unchanged, yet reborn repeatedly until it finds it way to liberation using the Gita and other scriptures as a guide Samsara: the cycle of rebirth which continues until brahman/nirvana is reached Karma: actions and their consequences; bad karma can only be overcome by achieving moksha, or the release that comes when one realizes that one cannot influence the process of karma Kashi: dying in the right city is a shortcut to moksha… HINDUISM Death is not that important During samsara death will occur many times; thus it is of little importance One death is merely a stage, a milestone, in a long process The continuing self has already passed on when a “person” dies (or is cremated) if one is good, the soul leaves through the brahmarandhra (a small opening in the crown of the head); if one is evil, through the anus HINDUISM The afterlife before reentering samsara Preta: an intermediate condition taken by the soul immediately after death Judgment and the afterlife: Early literature: the domain of Yama, the ruler of the ancestors: a place where families are reunited and the pain and sorrow of this life is removed Later and post-Vedic literature: vivid descriptions of hell-like places of torture and punishment (narakas), where the punishment fits the crime HINDUISM How is death observed? Meditation on God at the time of death: Ritual return of the dead on the funeral pyre: the soul can influence what form it will take next aided by namakirtana, or chanting the name of a god until one ceases to be aware of anything else the eye to the sun, the breath (atman) to the wind, the body to the plants Rg Veda 10.16.3 Ekoddista: ritual to render benign the deceased individual’s preta Sraddha: 16-stage ritual taking up to a year and including not only one deceased individual but also up to 4 generations of ancestors to construct an interim body for the preta Modern Medicine How Doctors took the Place of Priests at the Deathbed The Medicalization of Death In ancient times, the doctor’s presence at the deathbed was rare: this was the priest’s role When involved at all, the doctor’s role was merely to predict the time of death (so the priest could do his job) After the Enlightenment, it became a “status symbol” to die under medical care, as medicine was seen to be able to “do battle” with death Dissection enabled improved understanding of pathophysiology of death Diseases were being described and categorized New vision of “natural death” was thus available: death at the end of a long life as the result of a clinically identifiable illness Death may even be prevented (or at least delayed) by understanding disease C Seale. Constructing Death. Cambridge: CUP, 1998, pp. 76-78. Religion, Medicine and Death “… modern rationality, of which medicine is an example, is itself a religious orientation, providing an imagined community, rites of inclusion and membership, and guidance for a meaningful death.” Seale. Constructing Death. Cambridge: CUP, 1998, pp. 75-76. Death as Biological Imperative Cells are preprogrammed to stop dividing after a certain number of divisions, and then to die (apoptosis) DNA errors accumulate over time and with continued environmental exposures Cumulative effects of cell death impair organ functions needed to sustain life Teleologically, death may be adaptive at population level: people don’t compete with their offspring for scarce resources Searle. Constructing Death. Cambridge: CUP, 1998, pp. 35-36. Medical Definitions of Death Cardiopulmonary Death Previously easily diagnosed by irreversible cessation of respiration and circulation which necessarily led to death of all organs within a short time After advent of ventilators, death could not be equated with absence of vital signs of circulation and respiration since machines can fulfill these functions If this definition of death was used, organ harvesting for transplants would be jeopardized by deterioration of the organs during the time immediately after cessation of respiration and circulation Currently accepted in the USA as one of two valid definitions of death A Scholthauer and B Liang, “Definitions and implications of death.” Hematology/oncology Clinics of North America 16:6 (2002). Medical Definitions of Death Whole-Brain Death 1968: Harvard Medical School committee defines death as irreversible coma: “a state of unreceptivity and unresponsivity, with no movement, breathing, or reflexes, accompanied by a flat EEG” 1970: Kansas is first state to legally recognize “the absence of spontaneous brain function” as equivalent to cardiopulmonary death 1980: Uniform Determination of Death Act declares that “an individual who has sustained either (1) irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions, or (2) irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brain stem, is dead” Medical Definitions of Death Whole-Brain Death This definition means that healthy organs can be harvested as artificial ventilation and respiration are maintained It also implies that once a diagnosis of whole-brain death is made, further medical treatment is futile; this has financial implications: medical insurance generally will not cover that is not medically necessary, leaving families and hospitals with the bill for further “treatment” USA, Germany, Japan, and France all accept this definition of death Medical Definitions of Death Higher-Brain Death Applicable to PVS patients: those without brain functions that control emotion, cognition and consciousness but who maintain at least partial brain stem function In general, courts are reluctant to adopt this definition because the absence of higher, cortical brain activity is harder to prove with certainty, at least in the short term However, some courts have allowed “life”-sustaining treatment of PVS patients to be discontinued (e.g., Quinlan, Cruzan, Schiavo?) Modern Medical Death Rites Life insurance: to ameliorate the consequences of one’s death, to gain greater control over death Wills: to determine what happens to one’s possessions after death Death certificates: to enshrine in law the “cause of death” Autopsies: to identify the cause of death if not obvious Inquests: to identify the cause of death if suspected to be “unnatural” Burial of the body (+/- embalming) OR cremation and interment of ashes: to confine the deceased to a known “resting place” which can also serve as a memorial Death in Society: Doctors and Patients Nationality Ethnicity Class DOCTORS Differences in End-of-life Care Death in ICU preceded by decision to limit care: Decisions to withhold versus withdraw care (in a survey of western European physicians) Belgium: 65% Canada: 70% USA: 75% Israel: 91% 93% sometimes withheld treatment 77% sometimes withdrew treatment Physicians with strong religious beliefs (and those from countries with deeper religious roots such as Greece, Italy and Portugal) were less likely to withdraw life support Withdrawal of nutrition is considered acceptable in PVS patients: USA: 89% Britain: 65% Belgium: 56% Japan: 17% J-L Vincent, “Cultural differences in end-of-life care.” Critical Care Medicine 29:2 (2001). PATIENTS Differences in End-of-Life Decisions Nationality Canadian patients more likely to want the details of their terminal illness than patients in Europe or South America J-L Vincent, “Cultural differences in end-of-life care.” Critical Care Medicine. 29:2 (2001). PATIENTS Differences in End-of-Life Decisions Ethnicity: Cultures which are more individualistic, secular, pragmatic, scientific tend to prefer full open awareness (as opposed to cultures which are familial, sacred, traditional, emotional) In favor of closed awareness: Mexican, Japanese In favor of full open awareness: Anglos Most interested in carrying out wishes of the dying: Japanese Most wills and life insurance: Anglos C Seale. Constructing Death. Cambridge: CUP, 1998, pp. 179-181. PATIENTS Differences in End-of-Life Decisions Ethnicity: In USA, whites significantly more likely than blacks: to discuss treatment preferences before death to complete a living will to designate Durable Medical Power of Attorney to limit care in certain situations and withhold treatment before death S Hopp and S Duffy, “Racial variations in end-of-life care.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 48:6 (2000). PATIENTS Differences in End-of-Life Decisions Class: Persons of higher socioeconomic class 2.7 times more likely to desire full open awareness of a terminal diagnosis C Seale. Constructing Death. Cambridge: CUP, 1998, p. 179 The Individual “My Death” “I Will Die” What is required to understand the notion, “I will die”? To bridge the gap between what I’ve experienced of life to a construct of its negation? Self-awareness Logical thought Conceptions of: Probability Necessity Causation Time Finality Separation R Kastenbaum. The Psychology of Death. New York: Springer, 2000, pp. 30-35. Death and Psychological Development Developmental Stages Up to age 5 1. – – – 2. Death is not final Death is a diminution of aliveness Death involves separation Ages 5-9 – Death is final – – Death is not inevitable – if one is clever and lucky Death personification – death as a separate person Age 10 and older 3. – – Death is final Death is inevitable Death is universal – Nagy, in R Kastenbaum. The Psychology of Death. New York: Springer, 2000, pp. 51-53. Stages of Dying 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Denial Anger Bargaining Depression Acceptance E Kubler-Ross, in R Kastenbaum. The Psychology of Death. New York: Springer, 2000, pp. 216-217. Getting the Timing Right “The material end of the body is only roughly congruent with the end of the social self. In extreme old age, or in disease, when mind and personality disintegrate, social death may precede biological death. Ghosts, memories and ancestor worship are examples of the opposite: a social presence outlasting the body.” Euthanasia: social death is preempted by actively hastening biological death Hospice: social death is pushed back as far as possible until biological death occurs C Seale. Constructing Death. Cambridge: CUP, 1998, pp. 34, 184.