Class Example

advertisement

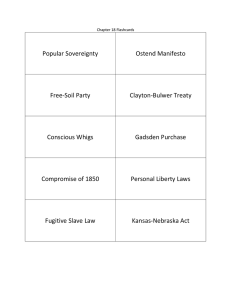

This is an example of communicating effectively through text because I was able to take a large piece of work, a book in this context, and condense it into a short writing. I provided a summary of the book, author and publishing information, and an analysis. All of these things I communicated effectively in a way that shows that I not only have a grasp of the content itself, but also am able to teach it well (in this case through text). Taylor Robertson February 6, 2013 On the Brink of Civil War John C. Waugh In John C. Waugh’s book, On the Brink of Civil War, Waugh describes the issues leading into the 31st Congress which began meeting in December of 1849. With the new territory acquired from the conclusion of the Mexican War, “the country seemed in critical danger of shattering over the issue of whether slavery would or would not be permitted in these new territories,” (4). Waugh explores the different debates of the men in Congress as they worked to reach what would come to be known as the Compromise of 1850. However, Waugh’s argument also shows that this compromise was only a temporary one. His thesis contends that “the Compromise of 1850 was a compromise only in the sense that it would be the last one before no compromise was possible. It had simply bought the Union a decade of time,” (190-191). Waugh, a journalist turned 19th century historian, has written six books pertaining to the time period leading to and during the Civil War. Waugh begins the book by discussing Washington D. C. as a symbol of a nation that was “clearly a work in progress,” and giving a brief background on the Missouri Compromise—the last political settlement before the Compromise of 1850 (2). He then presents the Wilmot Proviso which barred all slavery in newly acquired territories and the five issues the 31st Congress faced: California, New Mexico and Utah, Texas, Slavery and Slave Trade in the Capitol, and the Fugitive Slave Law. These issues, although complex, boiled down to the fact that the South believed “Congress had no right under the Constitution to legislate on slavery one way or the other,” whereas the North believed it did (26). The South thought they had a champion with the newly elected president, Zachary Taylor. However, Taylor’s cabinet convinced him that “Southerners, not Northerners, were behind all this trouble over slavery in the territories” and the South was “being unreasonable,” (39). Waugh increases the tension by demonstrating how challenging it was to select a speaker for the House (decided by plurality). “Instead of the lines of disagreement shortening, they were lengthening,” (59). Henry Clay of Kentucky came forth with a compromise. The compromise dictated that California should be admitted as a free state, governments would be established in the remaining Mexican War territory, Texas would release New Mexico and the United States would cover Texas’s debts, the Fugitive Slave Law would be strengthened, and slave trade but not slavery would be abolished in the Capitol. This asked “about an equal amount of concession and forbearance on both sides,” (75). John Calhoun fought against Clay’s compromise and argued instead for the Constitution as compromise. He even proposed an amendment requiring equilibrium of slave and free states. Calhoun basically promised that unless “aggression by the government and the North against the rights of the South” was stopped “the South would secede,” (93). Calhoun’s speech enraged many antislavery senators. However, the speaker that silenced them all was Daniel Webster on the 7th of March. Webster argued that slave laws were unnecessary in New Mexico and California due to their physical geography. He did not support the Wilmot Proviso and did support the strengthening of the Fugitive Slave Law despite being from the North. He did this because he spoke “out of a solicitous and anxious heart, for the restoration . . . of this Union so rich and so dear,” (103). While many Free-Soilers and abolitionists hated Webster’s stand, those who favored a compromise saw it as “a turning point, certainly bringing new support for accommodation,” (106). William Henry Seward, a senator from New York who also doubled as President Taylor’s political right hand, combated Webster’s arguments. Seward submitted that California should be let in immediately as a free state, and he stood strongly opposed to the Fugitive Slave Law. All these suggestions had been entertained before, but Seward introduced the idea of a higher law. He maintained “no compromises, no concessions, no yielding to the South. A higher law than the Constitution forbade it,” (113). President Taylor immediately abhorred this logic because “The Constitution is not worth one straw if every man is to be his own interpreter,” (114). Yet the controversial idea did spur senators to put forth new ideas for compromise. Senator Douglas once again advocated for popular sovereignty, while Senator Hunter opted for Southern rights or secession, and still Senator Chase once again promoted the adoption of the Wilmot Proviso. Throughout all the discussions one man always had something to say: the senator from Mississippi, Henry Foote. Foote decided to compile all the compromise resolutions Henry Clay intended to push through Congress one at a time into a single package. The package would be decided within a committee comprised of senators from six slave states, six free states, and one senator chosen by the other twelve. This, Foote argued, “was the only way to get the compromise passed in the House of Representatives and veto-proofed at the White House,” (127). However, other senators, including Clay himself, feared no senator could support the package fully if all the compromises were lumped together. Therefore it would never pass. In the midst of this, John Calhoun died, and many feared his ideas of disunion would be idealized with his death. Thus, Congress decided something must be done, and put the Committee to a vote. “Douglas moved that if the committee resolution failed, then the Senate should take up the California bill immediately,” (134). Finally after much discussion and a quarter year of waiting, the Committee of Thirteen got to work. The Committee decided to accept Clay’s original compromise options. The extremes of both sides were unhappy with the compromise package known as the “Omnibus Bill.” The Omnibus did not work as planned. However, the death of President Taylor revitalized a sense of union loyalty. Senator Downs from Louisiana stated “Let us, then, bury in the tomb of our departed President all sectional feelings and divisions, and unite,” (165). Taylor’s replacement, Millard Filmore, and his cabinet did favor compromise. The Omnibus had not worked, but Stephen Douglas stepped forward. “Douglas would now pick up the pieces of Clay’s compromise . . . and ram them through, one by one,” (179). Slowly the bills about Utah, then Texas, then California, then New Mexico, then the Fugitive Slave Act, and finally slave trade in the Capitol were all passed. All of the compromises went through both houses, and the president signed “the last of the bills, on September 20,” (184). At the end of it all, Congress spent 302 days reaching a compromise. The sources within the second half of the book are similar to those in the first half because both halves concentrate on newspaper articles and personal memoirs, probably due to Waugh’s journalism experience. While both halves are beautifully written, the second half is stronger based purely on the fact that the first half sets it up so well. Overall, On the Brink of Civil War provides a compelling narrative explanation of the Compromise of 1850 which despite its best intentions was “only a truce that would end ten years later in a death-dealing civil war,” (190).