TeachLivE vs. Role-Play: Comparative Effects on Special Educators

advertisement

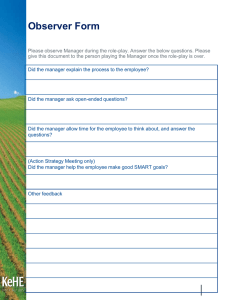

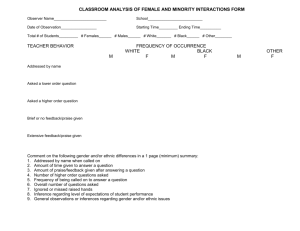

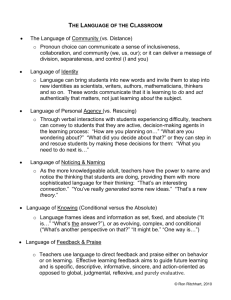

TeachLivE vs. Role-Play: TM Comparative Effects on Special Educators’ Acquisition of Basic Teaching Skills Melanie Rees Dawson & Benjamin Lignugaris/Kraft 1st National TeachLivE Conference Orlando, Florida, May 2013 TM Rationale A core goal of teacher preparation programs is to bridge the gap between knowledge and practice (Allsopp, DeMarie, Alvarez-McHatton, & Doone, 2006; Dieker, Hynes, Hughs, & Smith, 2008; Hixon & So, 2009). Training experiences are often constructed using situated learning as a theoretical foundation. Situated Learning: Knowledge acquisition requires realistic content and complexity Skill transfer depends on how closely practice opportunities match the situation in which information is to be applied (Brown, Collins, & Duguid, 1989) Rationale Simulating classroom scenarios is one strategy for situating learning for novice teachers. Role-playing is perhaps the oldest form of classroom simulation, dating back to the 1800’s (Brown, 1999). Recently, virtual simulations have emerged in teacher training programs (Hixon & So, 2009). TeachLivETM is a virtual classroom that can realistically represent the complexities that exist in actual classrooms (Dieker et al., 2008). Rationale TeachLivETM is an example of “technology-enhanced learning” in contrast to “traditional” approaches. Three types of Technology-Enhanced Learning used in university settings (Kirkwood & Price, 2013): (1) Replicating existing teaching practices: delivering instruction using technology (2) Supplementing existing teaching practices: creating additional resources or making resources/tools available for students to access at any time (3) Transforming the learning experience: Redesigning activities to provide active learning opportunities for students Purpose The purpose of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of practice sessions in TeachLivETM (a technology-enhanced approach) compared to practice sessions in role-play (a traditional approach) on preservice special educators’ development of essential teaching skills. Research Questions Study 1: (Foundation teaching skills) 1) To what extent will preservice special educators, who are trained to deliver opportunities to respond (OTR) and praise, demonstrate a higher response rate for the skill practiced in TeachLivETM Gen 1 than the skill practiced in role-play with colleagues, when assessed in TeachLivETM Gen 3? 2) To what extent will teachers who practice praise in TeachLivETM Gen 1, demonstrate a higher percentage of specific praise than teachers who practice praise in role-play with colleagues, when assessed in TeachLivETM Gen 3? Study 2: (Complex teaching skills) 3) To what extent will preservice special educators, who are trained to deliver error correction and praise around, demonstrate a higher percentage of correct steps for the skill practiced in TeachLivETM Gen 1 than the skill practiced in role-play with colleagues, when assessed in TeachLivE Gen 3? Methods: Participants 7 teachers in an Alternative Teacher Preparation (ATP) program Full-time special education teachers on letters of authorization Given $150 for participating in the study Two Groups: 3 teachers practiced praise in TeachLivETM and OTR in role-play (Group 1) 4 teachers practiced OTR in TeachLivETM and praise in role-play (Group 2) Methods: Participants Methods: Measures Dependent Variables OTR: The teacher asks an academic question and indicates if it is directed to the group or an individual student OTR rate= # OTR/mins (Goal= 4 per min) Praise: Positive teacher statements and gestures referring to student work or behavior General: positive statements or gestures that don’t specifically reference student work or behavior Specific: positive statements that directly reference student work or behavior Praise rate= # praise statements/mins (Goal= 4 per min) % Specific praise= (# specific/total praise) x 100 (Goal= >50%) Methods: Measures Assessment: Immediately following training sessions conducted in either TeachLivETM Gen 1 or role-play Generation 3 classroom Complexity: 4 academic errors (e.g. mispronouncing words, incorrect definition, poor example) 4 problem behaviors (e.g. cell phone ringing, talking out, tapping pen) 5 minute assessment session administered individually (Recorded and scored later) Measures: Reliability Interobserver Agreement: Primary Data Collector: 100% of assessment videos Second Data Collector: 31% of assessment videos OTR: Rate: 88.1% (71.4%-100%) Praise: Rate: 88.4% (70.8%-100%) Type: 96.5% (82.4%-100%) IOA= Agreements/(Agreements+Disagreements) x 100 Methods: Intervention Prior to Practice Sessions: Target Skill Instruction Video about each target skill Handout with examples/non-examples Quiz Lesson Plans Vocabulary Lesson (words & definitions) Teaching Formats (e.g. example/non-example, definition, sentence generation, sentence substitution) A short story that included the target vocabulary words 1 lesson plan for TeachLivETM, 1 lesson plan for role-play Methods: Intervention Training vs. Assessment TeachLivETM Gen 1 or role-play TeachLivETM Gen 3 No misbehaviors No academic errors 4 misbehaviors 4 academic errors Training vs. Assessment TeachLivETM Gen 1 or Norole-play misbehaviors No academic errors 1 lesson for TeachLivETM 1 lesson for role-play TeachLivETM Gen 3 4 misbehaviors 4 academic errors A new lesson for each assessment session Methods: Design Alternating Treatments Design Treatments alternated between TeachLivETM and Role-Play Target skills were counterbalanced across treatments and groups TeachLivETM Role-Play Group 1 Praise OTR Group 2 OTR Praise Advantages of an Alternating Treatments Design: Quickly compare effectiveness of two treatments Does not require baseline data or withdrawal Minimizes sequence effects (Cooper, Heward, & Heron, 2007) Results Results Results: Specific Praise Praise Targeted Praise Targeted Praise Targeted Study 2: Measures New Dependent Variables: Error Correction: When a student makes an academic error the teacher delivers a model, test, and delayed test. Model: The teacher provides the correct answer to the question Test: The teacher repeats the initial question Delayed Test: After one or more intervening responses, the teacher again asks the initial question. % correct Steps: (# correct steps/#possible steps) x 100 Praise Around: When a student exhibits a misbehavior that is persistent (5 s or more) or recurring (more than once) the teacher delivers the following steps: Step 1: The teacher praises another student who is exhibiting the desired behavior. The praise statement must be specific and identify the behavior that is incompatible with the problem behavior. Step 2: When the target student exhibits the desired behavior, the teacher praises the student using a specific praise statement that is incompatible with the problem behavior. % correct Steps: (# correct steps/#possible steps) x 100 Study 2: Intervention Study 2: Design Alternating Treatments Design (with baseline) Baseline data collected during Study 1 Treatments alternated between TeachLivETM and Role-Play Target skills were counterbalanced across treatments Group 1 Group 2 TeachLivETM Role-Play (Praise) (OTR) Praise Around Error Correction (OTR) (Praise) Error Correction Praise Around Study 2: Results Study 2: Results Surveys When both studies were complete, we administered two surveys: Presence Questionnaire: Surveyed the “realness” of the Gen 1 and Gen 3 classrooms, students, interactions, and teaching scenarios. (Adapted from a survey created by Aleshia Hayes) Social Validity: Surveyed the acceptability of the training procedures, and compared teacher experiences in TeachLivETM and Role-Play. Presence Questionnaire Findings: Majority of teachers understood the students’ different personalities Teachers were split on their perceptions of “realness” of the classroom and students, as well as their ability to interact as they would in a real classroom. Perceptions of “realness” depended on the level to which TeachLivETM matched their own classroom. Overall, the teacher’s degree of buy-in was the same for Gen 1 and Gen 3. The visual proximity to the students (zooming in and out) enhanced interactions in some situations, but may have hindered it in others. Social Validity Findings: The training and lesson materials were appropriate The feedback structures were helpful TeachLivETM is more similar than role-play to their own classrooms Social Validity Question: Which lab did you prefer? Why? TeachLivETM: 3 • • • Role-play: 4 “for a more real-life encounter” “I enjoyed the comradery of role-play, but it did not put you on the spot as much as TeachLivE.” “TeachLivE gave a variety of behaviors compared to role-play (more students).” • • • • “engaged the whole time” “face-to-face interaction” “enjoyed working with colleagues” “practice more on academic issues than behaviors” Question: If you were offered $50 for mastering a new skill in ONE session, would you choose to practice the skill in the TeachLivETM lab or the role-play lab? TeachLivETM: 5 Role-play: 1 *Although teachers were split on their buy-in and preference for TeachLivETM, they recognized that is it a powerful medium for practicing teaching skills. “I don’t know”: 1 Discussion Overall, teachers demonstrated higher rates and percentage of steps in the assessment session on the skills they practiced in TeachLivETM compared to the skills they practiced in role-play. These results suggest that TeachLivETM (technology-enhanced simulation) facilitates development of essential teaching skills more effectively than role-play (traditional simulation). Discussion Limitations: No Training Data Did teachers master the skill during training before generalizing to the assessment setting? No Classroom Data To what extent do teachers demonstrate the skills in their own classroom? Discussion Future Research: Focus on TeachLivETM Understand how many sessions it takes for teachers to become proficient with a specific skill, without being interrupted by other repertoires (multiple baseline) Collect training data as well as assessment data Generalization to real classrooms Regularly collect data in their own classrooms to investigate to what extent the levels of proficiency we see in TeachLivETM transfer to actual teaching. Select more homogeneous participants with similar teaching situations to TeachLivETM Secondary schools Teaching language arts References Allsopp, D. H., DeMarie, D., Alvarez-McHatton, P., & Doone, E. (2006). Bridging the gap between theory and practice: Connecting courses with field experiences. Teacher Education Quarterly, 33(1), 19-35. Brown, A. H. (1999). Simulated classrooms and artificial students: The potential effects of new technologies on teacher education. Journal of Research on Computing in Education, 32(2), 307–18. Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1), 32-42. Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2007). Applied Behavior Analysis (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall: New Jersey. Dieker, L., Hynes, M., Hughes, C., & Smith, E. (2008). Implications of mixed reality and simulation technologies on special education and teacher preparation. Focus on Exceptional Children, 40(6), 1-20. Hixon, E., & So, H.-J. (2009). Technology’s role in field experiences for preservice teacher training. Educational Technology & Society, 12(4), 294–304. Kirkwood, A., Price, L. (2013). Technology-enhanced learning and teaching in higher education: What is ‘enhanced’ and how do we know? A critical literature review. Learning, Media, and Technology, DOI:10.1080/17439884.2013.770404 Thank You! Melanie Dawson melanie.rees@usu.edu 801-505-3290 Ben Lignugaris/Kraft ben.lig@usu.edu 435-797-2382