Slide 1 - Farmasi Unand

advertisement

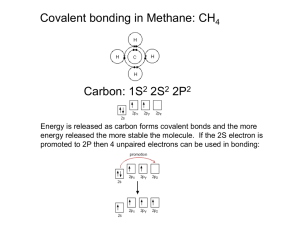

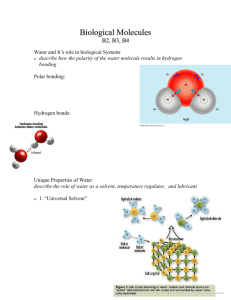

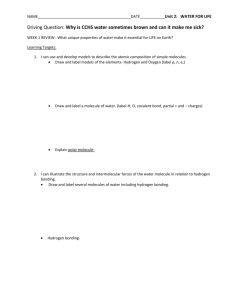

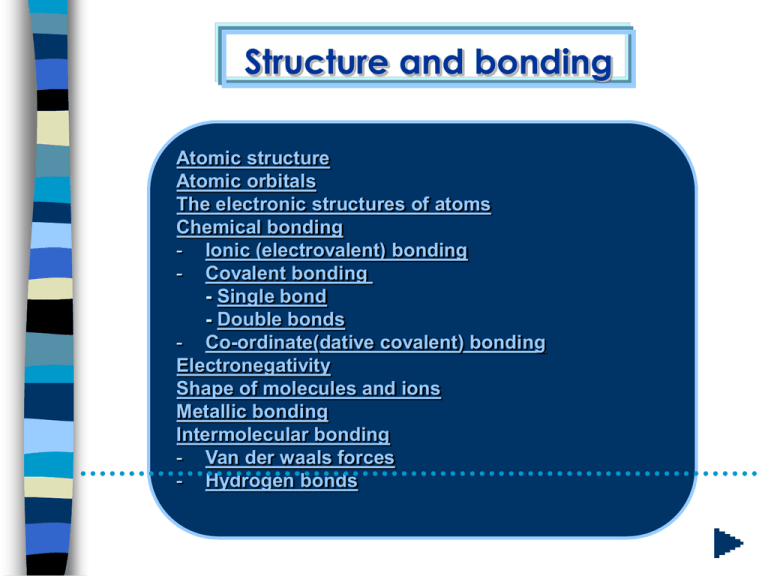

Structure and bonding Atomic structure Atomic orbitals The electronic structures of atoms Chemical bonding - Ionic (electrovalent) bonding - Covalent bonding - Single bond - Double bonds - Co-ordinate(dative covalent) bonding Electronegativity Shape of molecules and ions Metallic bonding Intermolecular bonding - Van der waals forces - Hydrogen bonds Atomic structure The sub-atomic particles Protons, neutrons and electrons. Relative mass 1 1 1/1836 Proton Neutron Electron Relative charge +1 0 -1 Isotopes, the number of neutrons in an atom can vary within small limits. Proton Neutron Mass number Carbon-12 6 6 12 Carbon-13 6 7 13 number of electrons = number of protons Atomic orbitals What is an atomic orbital? Orbitals and orbits Impossibility of drawing orbits for electrons.To plot a path for something you need to know exactly where the object is and be able to work out exactly where it's going to be an instant later. (The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle) Hydrogen's electron - the 1s orbital 2s orbital is similar to a 1s orbital except that the region where there is the greatest chance of finding the electron is further from the nucleus this is an orbital at the second energy level. there is another region of slightly higher electron density nearer the nucleus. "Electron density" is another way of talking about how likely you are to find an electron at a particular place. A p orbital is rather like 2 identical balloons tied together at the nucleus Fitting electrons into orbitals The order of filling orbitals Electrons fill low energy orbitals (closer to the nucleus) before they fill higher energy ones. Where there is a choice between orbitals of equal energy, they fill the orbitals singly as far as possible. The electronic structures of atoms Relating orbital filling to the Periodic Table d8 means Electronic structures of Cl 1s22s22p63s23px23py23pz1 ions Cl- 1s22s22p63s23px23py23pz2 Electronic structures of Na 1s22s22p63s1 ions Na+ 1s22s22p6 Electronic structures of Fe 1s22s22p63s23p63d64s2 ions Fe3+ 1s22s22p63s23p63d5 The electronic structures of atoms Ionisation energies are always concerned with the formation of positive ions. Electron affinities are the negative ion equivalent, and their use is almost always confined to elements in groups 6 and 7 of the Periodic Table. Chemical bonding IONIC (ELECTROVALENT) BONDING COVALENT BONDING - SINGLE BONDS - DOUBLE BONDS CO-ORDINATE (DATIVE COVALENT) BONDING IONIC (ELECTROVALENT) BONDING Ionic bonding in sodium chloride Sodium (2,8,1) has 1 electron more than a stable noble gas structure (2,8). If it gave away that electron it would become more stable. Chlorine (2,8,7) has 1 electron short of a stable noble gas structure (2,8,8). If it could gain an electron from somewhere it too would become more stable. The answer is obvious. If a sodium atom gives an electron to a chlorine atom, both become more stable. COVALENT BONDING- SINGLE BONDS As well as achieving noble gas structures by transferring electrons from one atom to another as in ionic bonding, it is also possible for atoms to reach these stable structures by sharing electrons to give covalent bonds. Methane What is wrong with the dots-and-crosses picture of bonding in methane? We are starting with methane because it is the simplest case which illustrates the sort of processes involved. You will remember that the dots-and-crossed picture of methane looks like this. There is a serious mis-match between this structure and the modern electronic structure of carbon, 1s22s22px12py1. The modern structure shows that there are only 2 unpaired electrons for hydrogens to share with, instead of the 4 which the simple view requires. You can see this more readily using the electrons-in-boxes notation. Only the 2-level electrons are shown. The 1s2 electrons are too deep inside the atom to be involved in bonding. The only electrons directly available for sharing are the 2p electrons. Why then isn't methane CH2? Promotion of an electron When bonds are formed, energy is released and the system becomes more stable. If carbon forms 4 bonds rather than 2, twice as much energy is released and so the resulting molecule becomes even more stable. There is only a small energy gap between the 2s and 2p orbitals, and so it pays the carbon to provide a small amount of energy to promote an electron from the 2s to the empty 2p to give 4 unpaired electrons. The extra energy released when the bonds form more than compensates for the initial input. Now that we've got 4 unpaired electrons ready for bonding, another problem arises. In methane all the carbon-hydrogen bonds are identical, but our electrons are in two different kinds of orbitals. You aren't going to get four identical bonds unless you start from four identical orbitals. sp3 Hybridisation The electrons rearrange themselves again in a process called hybridisation. This reorganises the electrons into four identical hybrid orbitals called sp3 hybrids (because they are made from one s orbital and three p orbitals). You should read "sp3" as "s p three" - not as "s p cubed". sp3 hybrid orbitals look a bit like half a p orbital, and they arrange themselves in space so that they are as far apart as possible. You can picture the nucleus as being at the centre of a tetrahedron (a triangularly based pyramid) with the orbitals pointing to the corners. For clarity, the nucleus is drawn far larger than it really is. The bonding in the phosphorus chlorides, PCl3 Phosphorus has the electronic structure 1s22s22p63s23px13py13pz1. There are 3 unpaired electrons that can be used to form bonds with 3 chlorine atoms. The four 3-level orbitals hybridise to produce 4 equivalent sp3 hybrids just like in carbon - except that one of these hybrid orbitals contains a lone pair of electrons. The bonding in the phosphorus chlorides, PCl5 Phosphorus has 1s22s22p63s23px13py13pz1. the electronic structure COVALENT BONDING - DOUBLE BONDS Hybridization sp2 Bonding in Benzene The Kekulé structure for benzene, C6H6 Kekulé was the first to suggest a sensible structure for benzene. The carbons are arranged in a hexagon, and he suggested alternating double and single bonds between them. Each carbon atom has a hydrogen attached to it. Problems with the Kekulé structure 1. Problems with the chemistry, because of the three double bonds, you might expect benzene to have reactions like ethene 2. Problems with the shape, benzene is a planar molecule (all the atoms lie in one plane), and that would also be true of the Kekulé structure. The problem is that C-C single and double bonds are different lengths. C-C 0.154 nm, C=C, 0.134 nm Bonding in Benzene 3. Problems with the stability of benzene, real benzene is a lot more stable than the Kekulé structure would give it credit for. This means that real benzene is about 150 kJ mol-1 more stable than the Kekulé structure gives it credit for. This increase in stability of benzene is known as the delocalisation energy or resonance energy of benzene. An orbital model for the benzene structure Benzene is built from hydrogen atoms (1s1) and carbon atoms (1s22s22px12py1). Each carbon atom has to join to three other atoms (one hydrogen and two carbons) sp2 hybrids, because they are made by an s orbital and two p orbitals reorganising themselves. The three sp2 hybrid orbitals arrange themselves as far apart as possible - which is at 120° to each other in a plane. The remaining p orbital is at right angles to them CO-ORDINATE (DATIVE COVALENT) BONDING NH3 + HCl NH4Cl CO-ORDINATE (DATIVE COVALENT) BONDING H2O+ HCl H3O++Cl- Measurements of the relative formula mass of aluminium chloride show that its formula in the solid is not AlCl3, but Al2Cl6. It exists as a dimer (two molecules joined together). The bonding between the two molecules is co-ordinate, using lone pairs on the chlorine atoms ELECTRONEGATIVITY Definition Electronegativity is a measure of the tendency of an atom to attract a bonding pair of electrons.The Pauling scale is the most commonly used. Fluorine (the most electronegative element) is assigned a value of 4.0, and values range down to caesium and francium which are the least electronegative at 0.7. What happens if two atoms of equal electronegativity bond together? What happens if B is slightly more electronegative than A? What happens if B is a lot more electronegative than A? Summary No electronegativity difference between two atoms leads to a pure non-polar covalent bond. A small electronegativity difference leads to a polar covalent bond. A large electronegativity difference leads to an ionic bond. The SHAPES OF MOLECULES AND IONS linear trigonal planar tetrahedral trigonal bipyramid pyramidal octahedral. bent or V-shaped. square planar The SHAPES OF MOLECULES AND IONS linear tetrahedral trigonal planar bent or V-shaped. METALLIC BONDING Metals tend to have high melting points and boiling points suggesting strong bonds between the atoms. Even a metal like sodium (melting point 97.8°C) melts at a considerably higher temperature than the element (neon) which precedes it in the Periodic Table. Sodium has the electronic structure 1s22s22p63s1. When sodium atoms come together, the electron in the 3s atomic orbital of one sodium atom shares space with the corresponding electron on a neighbouring atom to form a molecular orbital - in much the same sort of way that a covalent bond is formed. The difference, however, is that each sodium atom is being touched by eight other sodium atoms - and the sharing occurs between the central atom and the 3s orbitals on all of the eight other atoms. The electrons can move freely within these molecular orbitals, and so each electron becomes detached from its parent atom. The electrons are said to be delocalised. The metal is held together by the strong forces of attraction between the positive nuclei and the delocalised electrons. INTERMOLECULAR BONDING - VAN DER WAALS FORCES Intermolecular versus intramolecular bonds Intermolecular attractions are attractions between one molecule and a neighbouring molecule. The forces of attraction which hold an individual molecule together (for example, the covalent bonds) are known as intramolecular attractions. The origin of van der Waals dispersion forces Electrons are mobile, and at any one instant they might find themselves towards one end of the molecule, making that end d-. The other end will be temporarily short of electrons and so becomes d +.Imagine a molecule which has a temporary polarity being approached by one which happens to be entirely non-polar just at that moment. As the right hand molecule approaches, its electrons will tend to be attracted by the slightly positive end of the left hand one. This sets up an induced dipole How molecular shape affects the strength of the dispersion forces The shapes of the molecules also matter. Long thin molecules can develop bigger temporary dipoles due to electron movement than short fat ones containing the same numbers of electrons. Long thin molecules can also lie closer together - these attractions are at their most effective if the molecules are really close. For example, the hydrocarbon molecules butane and 2-methylpropane both have a molecular formula C4H10, but the atoms are arranged differently. In butane the carbon atoms are arranged in a single chain, but 2-methylpropane is a shorter chain with a branch. Butane has a higher boiling point because the dispersion forces are greater. The molecules are longer (and so set up bigger temporary dipoles) and can lie closer together than the shorter, fatter 2-methylpropane molecules. van der Waals forces: dipole-dipole interactions A molecule like HCl has a permanent dipole because chlorine is more electronegative than hydrogen. These permanent, in-built dipoles will cause the molecules to attract each other rather more than they otherwise would if they had to rely only on dispersion forces. It's important to realise that all molecules experience dispersion forces. Dipole-dipole interactions are not an alternative to dispersion forces - they occur in addition to them. Molecules which have permanent dipoles will therefore have boiling points rather higher than molecules which only have temporary fluctuating dipoles. INTERMOLECULAR BONDING - HYDROGEN BONDS The evidence for hydrogen bonding Many elements form compounds with hydrogen - referred to as "hydrides". If you plot the boiling points of the hydrides of the Group 4 elements, you find that the boiling points increase as you go down the group. The increase in boiling point happens because the molecules are getting larger with more electrons, and so van der Waals dispersion forces become greater. INTERMOLECULAR BONDING - HYDROGEN BONDS If you repeat this exercise with the hydrides of elements in Groups 5, 6 and 7, something odd happens. Although for the most part the trend is exactly the same as in group 4 (for exactly the same reasons), the boiling point of the hydride of the first element in each group is abnormally high. In the cases of NH3, H2O and HF there must be some additional intermolecular forces of attraction, requiring significantly more heat energy to break. These relatively powerful intermolecular forces are described as hydrogen bonds. The origin of hydrogen bonding The molecules which have this extra bonding are: Notice that in each of these molecules: The hydrogen is attached directly to one of the most electronegative elements, causing the hydrogen to acquire a significant amount of positive charge. Each of the elements to which the hydrogen is attached is not only significantly negative, but also has at least one "active" lone pair. Lone pairs at the 2-level have the electrons contained in a relatively small volume of space which therefore has a high density of negative charge. Lone pairs at higher levels are more diffuse and not so attractive to positive things. The origin of hydrogen bonding Consider two water molecules coming close together. The d+ hydrogen is so strongly attracted to the lone pair that it is almost as if you were beginning to form a co-ordinate (dative covalent) bond. It doesn't go that far, but the attraction is significantly stronger than an ordinary dipole-dipole interaction. Hydrogen bonds have about a tenth of the strength of an average covalent bond, and are being constantly broken and reformed in liquid water Hydrogen bond effect The boiling points of ethanol and methoxymethane show the dramatic effect that the hydrogen bonding has on the stickiness of the ethanol molecules: ethanol (with hydrogen bonding) 78.5°C methoxymethane (without hydrogen bonding)-24.8°C It is important to realise that hydrogen bonding exists in addition to van der Waals attractions. Comparing the two alcohols (containing -OH groups), both boiling points are high because of the additional hydrogen bonding due to the hydrogen attached directly to the oxygen - but they aren't the same. The boiling point of the 2-methylpropan-1-ol isn't as high as the butan-1ol because the branching in the molecule makes the van der Waals attractions less effective than in the longer butan-1-ol. Hydrogen bond effect Hydrogen bonding in organic molecules containing nitrogen Hydrogen bonding also occurs in organic molecules containing N-H groups - in the same sort of way that it occurs in ammonia. Examples range from simple molecules like CH3NH2 (methylamine) to large molecules like proteins and DNA. The two strands of the famous alphahelix in DNA are held together by hydrogen bonds involving N-H groups.