The Roots of the Amercian Revolution

advertisement

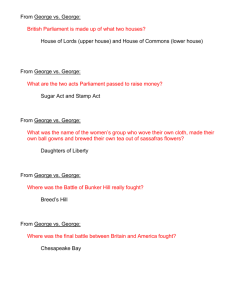

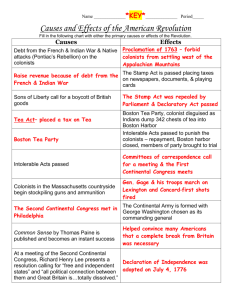

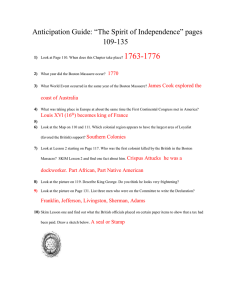

The Roots of the Amercian Revolution The Early Years… • When George III came to the throne in 1760 scarcely anyone in England or America foresaw independence for thirteen of the British colonies in North America. • Colonists were proud of their affiliation with Great Britain and satisfied with the prosperity they enjoyed as part of Britain's commercial empire. • Only in retrospect do the irritations that arose in the course of Britain's management of its vast empire appear to point toward revolution. Continued… • From the 17th century on, colonists had to deal with royal officials sent to protect the Crowns interests in North America. • The policies themselves were not at issue, since for the most part they harmonized well enough with the colonists' interests. The colonists worried more about that the money would end up in the pockets of the officials rather than the royal treasury. • The colonists' success in establishing the rights of their legislative assemblies, gave a measure of confidence that their liberty was secure. What Was London Thinking? • Imperial officials in London, though always uneasy about the assertiveness of the colonial legislatures, had no concerted plan for reform at the end of the French and Indian War in 1763. • The events that led to revolution in 1776 did not grow out of a British resolve to bring the loosely governed empire under control at last. • They were looking in another direction entirely when in 1765 the colonies exploded in rage at parliamentary taxation. Continued… • The Crown's ministers were simply seeking a way to finance the king's military policy. • During the French and Indian War the British government had taken financial responsibility for the defense of the colonies as well as provided military leadership and many of the troops. • Rather than demobilizing at the end of the war, George III with his minister William Pitt's backing chose to keep the army at near wartime strength of eighty-five regiments to be ready in the event of renewed hostilities with France. • The problem was how to pay for them. England was financially exhausted after the lengthy and costly war that had nearly doubled the national debt, and the country could not bear additional taxes. • The solution was to station large portions of the army in Ireland and America and require local support for the troops in each location. The Sugar Act, the Stamp Act, and the Townshend Duties were intended to help finance the £359,000 needed annually to sustain the troops in America. Sugar Act of 1764 • The American Revenue Act of 1764, or Sugar Act, confused the Americans. It was in the first place not a new tax but an alteration of an old customs duty. • To prevent trade with the French West Indies, Parliament in 1733 had passed a prohibitive tariff on sugar, molasses, and other goods imported from those islands. • The colonists lived with these annoying customs duties by evading them through smuggling. • They could scarcely object in principle to duties they had long acknowledged as legitimate. • In the second place, the Sugar Act reduced the duty, from 6d. on a gallon of molasses, for example, to 3d. • The difference was, of course, that mechanisms were put in place to collect the duty and American shippers faced having actually to pay it. • There were objections heard to the Sugar Act on grounds that it was intended for revenue, not regulation, and so was illegitimate, but the ambiguities were sufficiently great to blunt American opposition. The Stamp Act • The Stamp Act presented no such ambiguities. • It was a tax laid directly on the people for the express purpose of raising revenue. • To collect the tax the British ministry embossed stamps of varying values in sheets of paper and sold the paper to the colonists for use as legal documents, newspapers, and pamphlets. • No document written on unstamped paper had legal standing, and so the colonists were compelled to buy the stamps and pay the tax. • In Britain stamp taxes were considered inoffensive and easy to collect, but if Whitehall officials expected the colonists to agree for that reason, they soon realized that wasn’t going to happen. Continued… • The colonists at virtually every level of society, including many who later became Loyalists, rose in protest. • The colonial legislatures and a specially called Stamp Act Congress submitted complaining petitions to Parliament. • The people feared that the "Stamp Men" were benefiting from the tax. • The charges brought in newspapers and pamphlets against these men reflected the old suspicion about British colonial officials. America’s Argument to Parliament • They claimed as British subjects the right to tax themselves, and since the colonists could not be represented in Parliament, the taxes had to originate in their colonial assemblies. • The British believed that Parliament was sovereign over all the empire; everyone in it had to yield to its authority. • The colonists did not elect members to Parliament, but Parliament nonetheless represented the colonists as it did other groups—large cities in England among them— that did not have the right to elect members. • But the colonists could not acknowledge this notion of being "virtually" represented. • The trouble was Parliament was not affected by the taxes laid on the colonists. In fact, if those taxes ceased they could stand to increase taxes at home. TRICKERY • Then suddenly in 1766 the controversy seemingly dissolved. In the House of Commons William Pitt, the hero of the French and Indian War, made an eloquent if somewhat inconsistent plea for the colonies' right to tax themselves while affirming Parliament's supremacy in all other legislative matters. • Pitt's speech carried the day and the Stamp Act was repealed. • On the same day, however, Parliament passed a Declaratory Act that reasserted the right of Parliament to legislate "in all cases whatsoever." • In their rejoicing the colonists paid no heed to the merely verbal assertions. • In the long struggle with royal governors, they had become accustomed to such compromises; they knew they had won this one. • A few months later the duty on molasses was reduced to 1d. The colonists calculated that smuggling cost them about 1 1/2d. per gallon, so they willingly paid the lesser fee. The new duty brought substantial revenues to the Crown and all parties were content. The Boston Massacre • There was a tragic incident in 1770 when troops fired on a civilian crowd that was harassing them. • Some called it the Boston Massacre, but more levelheaded citizens recognized the deaths were an accident. • John Adams, a leader of the resistance to the British measures, defended the soldiers in court. • For the most part it seemed that good sense had prevailed and a compromise had been reached in the dispute with Parliament. Townshend Acts • • • • • • • • • Unfortunately, however, Britain still needed funds to sustain its American regiments. In 1767 the chancellor of the exchequer, Charles Townshend, proposed a new revenue measure that tried to make the most of American compliance with trade regulation such as the Sugar Act. Since the Americans objected to internal taxes like the stamp duties, Townshend proposed import duties on glass, lead, paints, paper, and tea similar to those on sugar and molasses. To his dismay, the Americans would have none of it. John Dickinson, in his Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, warned Americans that the Townshend Duties were every bit as much a revenue measure as the Stamp Act and should be repudiated. Citizens agreed. Merchants agreed to not import British goods- not just those subject to taxes but a broad range of other goods, even at a considerable cost to themselves. By 1769 only New Hampshire merchants had failed to enter a non-importation pact. When American imports fell by nearly a third, the ministry in London took notice. The new head of government, Lord North, led the way, and in 1770 the Townshend Duties were repealed. This time they only kept the duty on tea. Americans objected but could not sustain the painful non-importation agreements. As the news of repeal spread, the merchants resumed trade with Britain except for the importation of tea. Tea • The East India Company had fallen on hard times, and Parliament, in an attempt to bail out the lumbering giant, granted it privileges with grave implications for America. • The company's inventory of imported tea had built up in British warehouses. In 1773 Parliament decided that when tea was reexported to the colonies, the import duties paid when it was first brought into England would be remitted, enabling the company to retail the tea at a reduced price. • The company still had to pay the old Townshend Duty of 3d. a pound when the tea arrived in America, but there would be enough of a price differential to give the company a substantial marketing advantage even against smuggled Dutch tea. • Furthermore the company was allowed to sell through its own American agents rather than through middlemen, further reducing the price. The Boston Tea Party! • It is a little difficult to understand the American reaction to the Tea Act. No new duty had been imposed. Americans were no more obligated to buy the tea than before the act was passed. • But at all four major ports where tea shipments arrived—Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston—people resisted. • They interpreted the act as an attempt to bribe Americans into buying tea and paying the duty, thus opening the door to still more oppressive taxation. • In three ports the tea shipments were halted or sent back; in Boston Governor Thomas Hutchinson seemed resolved to land the tea at whatever cost. • To stop him, townspeople on December 16, 1773, dumped 342 chests of tea into the harbor. The Tea Act had brought the resistance movement back to life. The Hangover • The Boston Tea Party was the beginning of the end. All of England was outraged. In willfully destroying valuable private property the Americans had gone too far. • Parliament responded in March 1774 by closing the port of Boston to all trade and in May passed the Coercive Acts intended to restrict Massachusetts government. • The governor was authorized to appoint members of the Governor's Council rather than letting the lower house nominate them; he similarly was empowered to appoint judicial officials without the necessity of council approval; and town meetings were forbidden except to elect selectmen. Continental Congress • The ministry had hoped to isolate Massachusetts with these measures and show by example the fate that awaited other colonies that carried resistance too far. • Instead the colonies interpreted Massachusetts's fate as the doom that awaited them all if they failed to resist. • In September 1774 the First Continental Congress met in Philadelphia to protest the Coercive Acts and to organize a new non-importation movement. • In Massachusetts itself the new governor, Gen. Thomas Gage, decided not to keep the assembly in session, knowing it would do nothing but protest Britain's actions. • But in a truly revolutionary act, the assembly refused to disband and continued to meet as a Provincial Congress to take measures against the exercise of arbitrary power. • The Congress's main purpose was to declare the colony's rights and to enforce the non-importation agreement, but it soon assumed the form of a shadow government. • Tax revenues were diverted from the official treasury to the Congress. Fearing reprisals, it urged the town militias to make themselves ready and provided for the collection of arms. And So it Begins… • Governor Gage, a mild man who hoped to calm the aroused colonists, saw a revolutionary government forming before his eyes. • When he heard that a cache of arms had been stored at Concord twenty-one miles from Boston, he felt obligated to send troops to destroy it. • On the evening of April 18th the troops embarked from Boston Common to cross the Charles River to Cambridge. • At Lexington in the early morning hours they encountered a small, confused band of militiamen and shots were fired. • A few miles farther at Concord, militia from the surrounding towns put up more resistance. • Seeing they were outnumbered, the British began their retreat under heavy fire. The Revolution had begun. • http://www.earlyamerica.com/shot_heard.htm Social Changes Why Revolt? • The revolutionary movement began as a defense of the status quo. • All the colonists asked for in their first protests was the continuance of their traditional right as English subjects to consent to their own taxes. • Had Britain pulled back at nearly any point before 1775, the resistance would have died away. Why do it? • As the government became increasingly oppressive, the colonists had to ask why they obeyed at all. • Jefferson summed up a decade of thought in the Declaration of Independence when he wrote about "equality" and "inalienable rights." When a government fails in its duty to protect those rights, the people may organize a new government. • It was a simple line of thought, but unlike the initial protest against parliamentary taxation, the thinking was radical. What is Equality?? • The most prominent eighteenth-century meaning of equality was stated by John Locke: it meant no one had by nature the right to rule another human being without that person's consent. • Creatures of the same species, Locke said, "should also be equal one amongst another without Subordination or Subjection." People might differ in wealth, education, or manners, but no one had the right to govern another because of these advantages. • There was to be no separate rank above freeman with special privileges in the state. • After the Revolution, for the first time, the word aristocrat became a term of political opposition. Effect of this thought • The most significant effect from this thought of equality is that it made slavery untenable. • Following the Revolution, antislavery societies were formed in virtually all the northern states from Massachusetts to Virginia, abetting a movement already strong among the Quakers. • By legislation or judicial decision slaves were manumitted in most states from Pennsylvania north before 1800. • In 1787 Congress prohibited slavery in the Northwest Territory. • The southern delegates had insisted that the federal Constitution forbid interference with the slave trade for twenty years, and in 1808, when the prohibition expired, Congress stopped the importation of slaves. • But there progress halted. Slavery remained an institution in the states from Maryland south and spread into new states in the Southwest. The revolutionary idea had run up against the vested interests of planters whose economy and way of life were founded on slavery. Effects on the Church • One other institution came under attack in the name of revolutionary equality—the church. • Americans did not bear a grudge against the established church as the French or the English did, mainly because the American religious establishments exercised so few privileges and so generously tolerated dissenters. • As children of the Enlightenment, the American revolutionaries believed that the will to resist tyranny originated in the mind. People claimed their rights because they understood what they were. • The Anglican church in Virginia was anything but an overpowering intellectual influence in the state, yet Jefferson counted among his greatest achievements passage in 1786 of the Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom. • The New England states were slower to disestablish their Congregational churches (Connecticut in 1818 and Massachusetts in 1833), but the principle enunciated in the First Amendment that Congress should make no law respecting an establishment of religion eventually prevailed. Warfare The Beginning… • The encounters at Lexington and Concord were followed by the capture of Fort Ticonderoga (1775) and Crown Point (1775) in New York by Benedict Arnold and Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys. • The Second Continental Congress met in May and appointed George Washington commander in chief of the colonial forces. • John Dickinson drafted the Olive Branch Petition, sent to King George III, requesting that he seek a peaceful solution to the conflict • The king refused to receive the document and declared the colonists out of his allegiance and protection. • The British won a costly victory in Boston at the Battle of Bunker Hill (Breed's Hill) (1775) – suffering heavy casualties and winning the battle only after colonists ran out of ammunition. • Henry Knox oversaw the transportation of heavy artillery from Fort Ticonderoga across Massachusetts to Dorchester Heights, south of Boston, where the cannons could command the city below. • Brig. Gen. William Howe realized he could not hold the city, so he evacuated his troops to Canada on March 17. • In January 1776 Thomas Paine wrote his pamphlet Common Sense, jolting Americans to rally behind the cause of independence. • On July 2, 1776, a declaration proposed in June by Richard Henry Lee was presented to Congress, calling for independence. • Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence, drafted by Thomas Jefferson, on July 4, 1776. • By late 1776 General Howe had taken New York City and driven Washington and his small forces from Long Island and Manhattan and into New Jersey. • Washington, taking a desperate chance, crossed the Delaware River and attacked the Hessians at Trenton, New Jersey, on Christmas Day, surprising and defeating them. • This victory, along with another at Princeton, gave the Patriots new hope. At the end of the year, Paine's pamphlet The Crisis (1776) inspired the Patriots to continue their fight. • In the summer of 1777 Howe launched a campaign to seize Philadelphia. • He captured the city, but the Continental Congress quickly moved to York. • A British army moved south from Montreal to join British forces moving east from Lake Ontario and north from New York City. • The armies were to meet in Albany, splitting New York in two, securing the Hudson Valley, and isolating New England from the rest of the colonies. • Instead of moving north, Howe decided to take Philadelphia. • Gen. John Burgoyne, moving south, sent a raiding party to gather supplies but was defeated by Patriot forces at the Battle of Bennington, Vermont. • When Burgoyne's troops met a more powerful American army under Horatio Gates and Benedict Arnold at the Battle of Saratoga, the British were decisively defeated. • The American victory at Saratoga convinced the French that the Americans could win the war; agreeing to ally with the colonists, France entered the war against England. • Driven from Philadelphia by Howe, Washington wintered at Valley Forge (1777-78) where the German drillmaster Baron Friedrich von Steuben whipped the American soldiers into a well-disciplined force The Final Battles • The British changed their strategy in 1778 and moved into the South, expecting heavy Loyalist support. • They captured Savannah, Georgia, and Charleston, South Carolina. • The Americans, however, were victorious at King's Mountain, North Carolina, in 1780. In 1781 Gen. Nathanael Greene and Gen. Daniel Morgan took charge of the American armies in the South. • Gen. Charles Cornwallis and the British forces retreated to Yorktown, Virginia. • French forces arrived at Rhode Island under Gen. Jean Rochambeau and the French fleet arrived under Adm. François DeGrasse, blockading the entrance to Chesapeake Bay. • The armies of Washington, the Marquis de Lafayette, and Rochambeau marched south and began their siege of Yorktown on September 28, 1781. On October 17, Cornwallis surrendered. • With the American victory at Yorktown, the British lost their desire to continue the war. • In March 1782 the House of Commons voted to abandon the effort. Lord North's government fell, and the new ministry under Lord Rockingham opened negotiations with the American peace commissioners The Results • The United States sent Benjamin Franklin, John Jay and John Adams to negotiate the terms of the peace. • By the Treaty of Paris September 3, 1783, Great Britain recognized the United States as an independent nation. • The Great Lakes and Canadian border became the northern U.S. boundary, the Mississippi River the western boundary, and Spanish Florida the southern boundary. • The treaty also gave Americans fishing rights off the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. • An estimated 4,000 to 5,000 Americans died during the conflict, and British deaths totaled about 10,000. Why did America Win? • Despite their superior numbers, the British operated in a hostile environment that repeatedly defeated all efforts to put down rebellion. • As much as anything that fact accounts for their defeat. • It is true that as the war dragged on Americans were slow to enlist, reluctant to pay for still more provisions, and heartily tired of the conflict. • In the final analysis it was the refusal of the civilian population to give up and the determination of hundreds of ill-trained, poorly supplied militia companies to harass the enemy that weighed most heavily in the defeat of the British forces in America