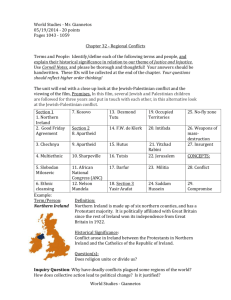

IE_4Q2015 - Research Repository UCD

advertisement