Labour supply and child care in a discrete choice model

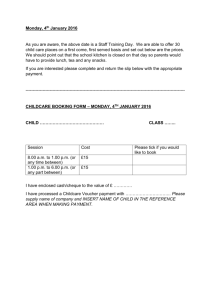

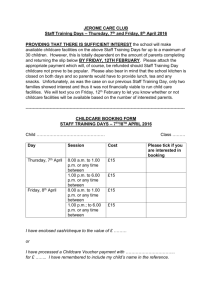

advertisement

MOTHERS’

EMPLOYMENT: THE IMPACT OF

TRIPLE RATIONING IN CHILDCARE IN

FLANDERS

Dieter Vandelannoote

Pieter Vanleenhove

André Decoster

Joris Ghysels

Gerlinde Verbist

(University of Antwerp)

(University of Leuven)

(University of Leuven)

(University of Maastricht)

(University of Antwerp)

OVERVIEW

Literature on employment and childcare

Childcare in Flanders: triple rationing

Labour supply model

Results

Conclusions

LITERATURE

-

-

Childcare touches upon

Budget constraints of parents

Preferences of parents

Modelling preferences for childcare is

demanding

Disentangle preferences from rationing

Identify heterogeneity in preferences

Often strong assumptions are made (e.g. Wrohlich, 2011,

assumes market supply to cover all excess demand in

Germany)

LITERATURE

Budget constraint approaches

-

Cost of working model (vs. simultaneous model)

-

In other words: it assumes childcare services to cover for

parental working time

-

With individually observed rationing (e.g. Kornstad and

Thoresen, 2007): individual choice sets are constructed

-

Without individually observed rationing (e.g. Del Boca and

Vuri, 2005): choice set is limited based on a simulated offer

probability of formal childcare

CHILDCARE IN FLANDERS: TRIPLE

RATIONING

-

-

Pre-primary education is generalised from

age 3

For children younger than 3:

Formal childcare (↗):

Supervision by Child and Family

Subsidized (59%) vs non subsidized (41%)

Child-minders vs day nurseries

Informal childcare (↘):

Mainly grandparents

CHILDCARE IN FLANDERS: TRIPLE

RATIONING

Although 70% of children younger than 3 is regular

user of formal childcare in 2005

Although 76% of mothers of children younger than 3

were gainfully employed in 2005

There are strong indications of preference

heterogeneity and rationing in Flanders:

-

When asked what kind of service they would prefer to use, parents often

indicate another type of childcare than the one used

A 2007 survey indicated that 10% of the parents was not able to secure a

suitable childcare service for their child after 6 months of searching

Supply grows only slowly

In our 2005 survey, 70% of non-employed mothers (unemployed or

inactive) indicated they would be willing to work, if suitable childcare

were available

CHILDCARE IN FLANDERS: TRIPLE

RATIONING

Costs for parents vary greatly according to the

type of service:

-

Informal childcare: free

-

Formal subsidized childcare: income dependent price scheme

(1,25 – 22 euro per day, before tax deduction, 2005)

-

Formal non subsidized childcare: suppliers can set prices

freely (average of 18 euro per day, before tax deduction, 2005)

-

We assume parents to act in a stepwise fashion:

informal → formal subsidized → formal non subsidized

LABOUR SUPPLY MODEL

Random utility model with discrete budget

constraint:

-

Random utility model: Vi , j U i ((T hi , j ), Ci , j | X i ) i , j

-

Discrete budget constraints:

-

Calculate household budget for every alternative, taking into

account:

1. wage (expected)

2. household characteristics Xi

3. tax-benefit rules

4. expected cost of childcare

= {0, 20, 32, 40}

LABOUR SUPPLY MODEL

Relies for estimation on McFadden’s (1974)

multinomial logit model:

Requires a specification for the utility function.

We use a quadratic form:

U i ((T hi , j ), Ci , j | X i ) c .[Ci , j ] cc .[Ci , j ]2

f ( X i ).[T hi , j ] ff .[T hi , j ]2

fc .[T hi , j ].[Ci , j ]

LABOUR SUPPLY MODEL + RATIONING

IN CHILDCARE SECTOR (1)

Double-hurdle model (as in Bargain et al, 2006)

assuming the likelihood of an offer (i.e. total rationing

to be equal across various labour market intensities

))

LABOUR SUPPLY MODEL + RATIONING

IN CHILDCARE SECTOR (2)

In the budget constraints, we incorporate

the expected cost of childcare:

E[cost hj] = [p(informal care offer) * 0] +

[(1- p(informal care offer) * p(subsidized care offer) *

cost(subsidized care hj)] +

[1- p( subsidized care offer) * p(non subsidized care

offer) * cost(non subsidized care hj)]

LABOUR SUPPLY MODEL

-

Effective offer of childcare derives from a

bivariate binary process:

Effective offer (0/1) = effective demand (0/1) * effective

supply (0/1)

We use a partial observability probit model

to estimate three probabilities in sequential

order (Poirier, 1980)

LABOUR SUPPLY MODEL

-

-

-

Informal care (grandparents):

supply: number, health status, employment status,

distance

demand: preference indicator of both mother and father

Formal subsidized childcare:

supply: municipal structure, search skills of the parents

demand: preferences indicators + likelihood of an offer in

informal care

Formal non subsidized childcare:

supply: municipal structure, search skills of the parents

demand: preferences indicators + likelihood of an offer in

both informal care and subsidized childcare

LABOUR SUPPLY MODEL

Predicted probability

(mean values)

Grandparents

.34

Subsidized care

.79

Non-subsidized care

.51

Total

.94

LABOUR SUPPLY MODEL

-

Estimate budget constraints using Euromod

Use data of the 2005 FFCS (Flanders

Families and Care survey). We focus on:

Couple families

With a child between 6 and 35 months

Both partners available for the labour market

No self employed

No handicapped child

Male partner working in a fulltime job (>90%)

512 couples

RESULTS

Maximum likelihood

estimates of the

parameters of the

quadratic utility

function

Statistically highly

significant

bc

bcc

Std.

Coefficient Error

P-value

22.80

3.94 .000

-1.82

0.34 .000

bf

Age

Age squared

Children 0-3

Children 4-6

Children 7-9

Higher education

Constant

-0.03

0.00

0.04

0.05

0.03

-0.02

1.27

0.01

0.00

0.01

0.01

0.01

0.01

0.25

.015

.008

.001

.000

.018

.069

.000

bff

bfc

-0.00

-0.09

0.00

0.02

.000

.000

RESULTS

Reflects inclination of

indifference curve at

(C = 2000 and h = 40)

Different subgroups

“How much income do

I want to give up for

one hour of additional

non-working time?”

Subgroup

MRS

(euro)

Whole sample

-30.3

No university

-31.4

University degree

-29.7

One child 0-3

-30.0

Two children 0-3

-31.4

Three children 03

-36.8

RESULTS

% LFP

% change in

total working

hours

Base

82.4

Increase gross wage +10%

83.2

+2.5

Increase childcare cost +10%

82.2

-0.7

Make childcare cost = 0

83.8

+5.8

Take away rationing

(i.e. make actual = desired

working hours)

95.3

+14.3

CONCLUSIONS

-

-

We extend the discrete labour supply model

with:

Overall childcare service rationing

Variation in the cost of childcare services depending on the

likelihood of informal, formal subsidized and formal non

subsidized childcare

Results indicate that in the current Flemish

situation

Prices are not of paramount influence

Childcare rationing withholds a considerable number of

mothers from the labour market