Policy Scan - Healthy Communities Partnership Haldimand and

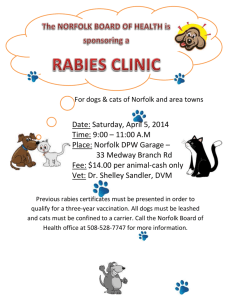

advertisement