Input-based hypothesis testing

advertisement

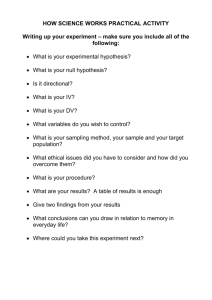

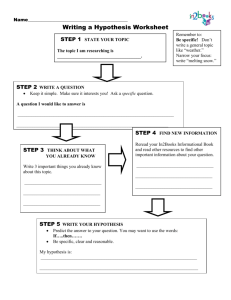

Hypothesis Testing Important words to know within language acquisition Comprehensible input Input in relation to intake Hypothesis formation Hypothesis testing Implicit and explicit knowledge Feedback Generalization 1 The acquisition – learning hypothesis In modern linguistics, there are many theories as to how humans are able to develop language ability. According to Stephen Krashen's acquisition-learning hypothesis, there are two independent ways in which we develop our linguistic skills: acquisition and learning. [1] This theory is at the core of modern language acquisition theory, and is perhaps the most fundamental of Krashen's theories on Second Language Acquisition. Acquisition Acquisition of language is a subconscious process of which the individual is not aware. One is unaware of the process as it is happening and when the new knowledge is acquired, the acquirer generally does not realize that he or she possesses any new knowledge. According to Krashen, both adults and children can subconsciously acquire language, and either written or oral language can be acquired.[1] This process is similar to the process that children undergo when learning their native language. Acquisition requires meaningful interaction in the target language, during which the acquirer is focused on meaning rather than form. [2] Learning Learning a language, on the other hand, is a conscious process, much like what one experiences in school. New knowledge or language forms are represented consciously in the learner's mind, frequently in the form of language "rules" and "grammar" and the process often involves error correction.[1]. Language learning involves formal instruction, and according to Krashen, is less effective than acquisition. 2 The monitor hypothesis The monitor hypothesis asserts that a learner's learned system acts as a monitor to what they are producing. In other words, while only the acquired system is able to produce spontaneous speech, the learned system is used to check what is being spoken. Before the learner produces an utterance, he or she internally scans it for errors, and uses the learned system to make corrections. Self-correction occurs when the learner uses the Monitor to correct a sentence after it is uttered. According to the hypothesis, such self-monitoring and self-correction are the only functions of conscious language learning.[1] The Monitor model then predicts faster initial progress by adults than children, as adults use this ‘monitor’ when producing L2 (target language) utterances before having acquired the ability for natural performance, and adult learners will input more into conversations earlier than children.[citation n 3 The natural order hypothesis Like first language learners, SL learners seem to acquire the features of the target language in predictable sequences. Contrary to intuition, the rule which is easy to state (Thus to learn) is not the first to acquire. Fx the rule for adding –s to a third persons singular verbs in the past tense is easy to state, but even advanced learners fail to apply the –s. 4 The input hypothesis According to the comprehensible input hypothesis (originally called the input hypothesis), we acquire language only when we receive comprehensible input (CI). This hypothesis developed by Stephen Krashen is one of the most prominent modern theories in the fields of first language acquisition and second language acquisition (SLA). If i represents previously acquired linguistic competence and extra-linguistic knowledge, the hypothesis claims that we move from i to i+1 by understanding input that contains i+1. Extra-linguistic knowledge includes our knowledge of the world and of the situation, that is, the context. The +1 represents new knowledge or language structures that we should be ready to acquire.[1] The comprehensible input hypothesis can be restated in terms of the natural order hypothesis. For example, if we acquire the rules of language in a linear order (1, 2, 3...), then i represents the last rule or language form learned, and i+1 is the next structure that should be learned.[2] It must be stressed however, that just any input is not sufficient, the input received must be comprehensible.[1] According to Krashen, there are three corollaries to his theory. 5 The affective filter hypothesis The affective filter is an impediment to learning or acquisition caused by negative emotional ("affective") responses to one's environment. It is a hypothesis of second language acquisition theory, and a field of interest in educational psychology. According to the affective filter hypothesis, certain emotions, such as anxiety, self-doubt, and mere boredom interfere with the process of acquiring a second language. They function as a filter between the speaker and the listener that reduces the amount of language input the listener is able to understand. These negative emotions prevent efficient processing of the language input.[1] The hypothesis further states that the blockage can be reduced by sparking interest, providing low anxiety environments and bolstering the learner's self-esteem. Input - intake Danich children are exposed in millions of ways to the English language. As a contrast you could look at a Danish student learning French and the limited exposure they get. Learners can interpreted directly by means of the knowledge they have of the foreign language (Their ‘interlanguage’). Rules matches IL system. The learners can interpreted inputs by means of inferencing strategies, by making qualified guesses to meaning of input (top-down processing) Comprehensible input: that can be understood by somebody. Intake: is input which affects the learner’s existing knowledge of a foreign language. Hypothesis formation Learners are often unconscious about the hypotheses they form and they are not defined relative to conscious beliefs, but relative to the cognitive representation of the learner’s interlanguage knowledge. Those parts of an interlanguage system which contains rules/items and which are ready to incorporate new hypotheses are PERMEABLE. Opposite is FOZZILIZATION which refers to the state where the cognitive representation is inflexible and relevant parts of the system are generally unwilling to incorporate new hypotheses. Hypothesis-formation based on L1 will be referred to as transfer, whereas the term generalization refers to hypothesis-formation based on interlanguage knowledge. Generalization: This is the process of extending existing interlanguage knowledge to new context. Intralingual: from within the language Transfer: Carrying over from the mother tongue or from other foreign language into IL refers to as transfer. Interlingual: from other language. There are two factors which are particularly important for L1-based hypothesis formation. 1. The amount of formal and functional similarity between the L1 and L2. 2. Is the learner willing to transfer? Input-based hypothesis testing 1. Identification phase: Responsible for which parts of the input gets assimilated into the learner’s 1L system (Intake) 2. Interpretation phase: Responsible for which parts of the input gets assimilated into the learner’s 1L system (Intake) 3. Conclusion phase: Concerned with the processes seen from the learner’s end, with what happens to existing 1L language when new knowledge is introduced. Implicit and explicit knowledge Implicit: linguistic knowledge that the learner kan use, but not describe. Fx p 191. Explicit knowledge: Some can describe, but not ness use.