Week 13.5 Docu Lecture 2 Documentary Ethics

advertisement

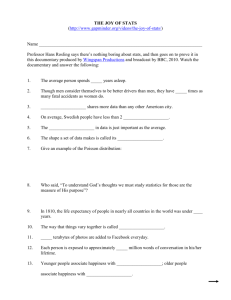

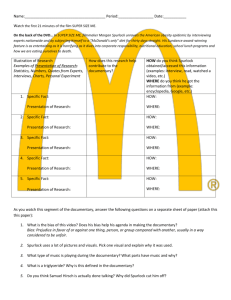

Follow Up on Lara Logan http://www.cbs.com/primetime/60_mi nutes/video/?pid=S3k3QHnsVnz2mhjU Z7qrc7Lp01lQWCtG&vs=homepage&pl ay=true Short Film “9 Star Hotel” • http://www.pbs.org/pov/9starhotel/9starhotel _fullfilm1.php • Observational style • http://www.pbs.org/pov/9starhotel/video_int erview.php Documentary Lecture 2 Subgenres and Ethical Issues • Develop a deeper understanding of different genres and styles present within the documentary production industry. • Explore ethical issues of documentary production Subgenre’s of Documentary • In his 2001 book, Introduction to Documentary (Indiana University Press), Bill Nichols defines the following six modes of documentary. From Nichols, Bill. Introduction to Documentary (Indiana University Press), The Poetic Mode • “'reassembling fragments of the world', a transformation of historical material into a more abstract, lyrical form, usually associated with 1920s and modernist ideas.” • For example, the “City Symphony” films. From Nichols, Bill. Introduction to Documentary (Indiana University Press), The Expository Mode • “'direct address', social issues assembled into an argumentative frame, mediated by a voice-of-God narration, associated with 1920s-1930s, and some of the rhetoric and polemic surrounding World War Two” • For example, John Grierson’s film about the post office. From Nichols, Bill. Introduction to Documentary (Indiana University Press), The Observational Mode • “as technology advanced by the 1960s and cameras became smaller and lighter, able to document life in a less intrusive manner, there is less control required over lighting etc, leaving the social actors free to act and the documentarists free to record without interacting with each other” From Nichols, Bill. Introduction to Documentary (Indiana University Press), The Participatory Mode • “the encounter between film-maker and subject is recorded, as the film-maker actively engages with the situation they are documenting, asking questions of their subjects, sharing experiences with them. Heavily reliant on the honesty of witnesses” – For example, “Chronicle of a Summer” (1959), where filmmaker provokes questions. From Nichols, Bill. Introduction to Documentary (Indiana University Press), The Reflexive Mode • “demonstrates consciousness of the process of reading documentary, and engages actively with the issues of realism and representation, acknowledging the presence of the viewer and the modality judgments they arrive at. Corresponds to critical theory of the 1980s.” – For Example: Vertov’s “Man With a Movie Camera” (1929) From Nichols, Bill. Introduction to Documentary (Indiana University Press), Performative Mode • “acknowledges the emotional and subjective aspects of documentary, and presents ideas as part of a context, having different meanings for different people, often autobiographical in nature” – Different from participatory mode as it is more subjective. – For example, Supersize Me (2008) From Nichols, Bill. Introduction to Documentary (Indiana University Press), Ethical Concerns • Conflict between “artistic” ideals and profit – Documentary makers see themselves defending a “higher truth” – But they “constantly compete in a business environment.” – This can lead to ethical questions. Center for Social Media. “Honest Truths: documentary Filmmakers on Ethical Challenges in Their Work.” September 2009. Ethical Concerns: Two Types • 1. Relationship between filmmaker and subject: how to fairly tell the stories of the people portrayed in your film. • 2. Relationship between filmmaker and audience: how to create trust between audience and filmmaker. Subject • Do no harm • Protect the vulnerable • Filmmaker / documentarian often has more social or economic power than the subjects of the film. – “I am in their life for a whole year. So there is a more profound relationship, not a journalistic two or three hours.” • Sometimes the subject behaves unethically. Is it right to show that behavior? – “revealing a subject’s weaknesses or positions that the audience is likely to find laughable or repellant can be justified when they are taking advantage of other people or when they are so completely convinced of their own rightness, they would be happy with their portrayal. You don’t owe them more than that.” Protecting the Subject • “It’s important to lift people up who tell tehir stories, as opposed to making them victims. It’s a moral decision not to enter their lives to only show how poor they are.” – Social Protection: One filmcrew prevented a teenager from bullying his classmate when the teacher left the room. – Legal protection: Another filmmaker’s subject told a story about trying to bring her son across the border illegally. “It’s a powerful story, and its important plot-wise. We consulted with [an] immigration attorney . . . to figure out which of those statements could put the character at risk.” The filmmaker removed an incriminating line, while keeping the general information and preserving the filmmaker’s interests as a creator. “ (11) Allowing Subjects to Share Decision Making • Most have subjects sign legal releases. • But many admitted they gave their subjects more leeway than the releases allowed. • Gordon Quinn: “We are not journalists; we are going to spend years with you. Our code of ethics is very different. A journalist wouldn’t show you the footage. We will show the film before it is finished. I want you to sign the release, but we will really listen to you. But ultimately it has to be our decision.” Allowing Subjects to Share Control of Final Cut • Some directors allow subjects to be part of editing process:" I don’t want to make films where people feel like they are being trashed . . . We make the films we make because of these relationships we build. It’s important to us that people agree with the film.” (14) • Usually an informal, not legal decision. • Other directors feel this would “delegitimize the film” and jeopardize its independent vision. – “Its our work and our interpretation” (14) Paying Subjects • Major concern – payment can “skew reality” as people might participate for personal gain. • “Many filmmakers believed that payment was not only acceptable but a reasonable way to address the power differential, even though payment often sufficed only to cover costs of participation. “ (13) – Errol Morris, Standard Operating Procedure Two Opposite Decisions • One filmmaker worked with a family for two years. He never discussed payment but after year one, he offered them $5000 each because he felt that it was “an important gesture” (13) • Another woman was making a film about immigrants to America. They asked for money but she refused, “You cross the line, are you the filmmaker or their best friend in America? . . . It was awkward for them but I did not want to set a precedent.” (14) Sharing Profits • Hoop Dreams (1992) shared profits with everyone who had screen time. Deception • One director secured an interview with a prisoner by writing on BBC letterhead – he wasn’t BBC> Viewers and the Film • If filming is about relationship with subject, • Editing is about relationship with audience. • “I have to be careful not to abuse the friendship with the subject, but it’s a rapport that is somewhat false,” said one. “In the edit room . . . you decide what your film is going to be, you have to put your traditional issues of friendship aside. You have to serve ‘the truth.’” (15) “Truth” • Filmmakers are aware that “choices of angles, shots, and characters were personal and subjective” (18) • Many of them referred to Grierson’s quote about “creative treatment of actuality” • Framing and Editing • Stating, Restaging, Events – “restaging routine or trivial events such as walking through a door was part and parcel of the filmmaking process and was “not what makes the story honest.” (18) – But some went further: “Another recalled asking her subjects to stage an annual event earlier in the year than it would happen in real life: I would not want to put words in people’s mouth, or edit them in a way that’s not leading to the larger truth. But I feel like it’s important to get the big-picture truth of the situation on camera.” • Archival Material – Photographs and film from the past (like Now!) – Need to be careful to establish context for any archive you use. – Don’t just use archive for “tone” – “you put it out there as truth. Someone else will be culling footage from your film. If it’s 1958 Manila . . . you have to be truthful.” (21) Ethical Concerns: Subject • Cable producers want “sexy” stories that make money. One director said: “to look at a homicide that happened seven years ago, and look at who did it—it’s good entertainment. It has no ethical or redemptive value . . . It’s not increasing anyone’s knowledge.” Ethical Concerns • Trying to get the shots you need on a limited budget. • One director described how guilty he felt after letting a animal handler “break a rabbits leg” to get a better shot. • “For us to inflict pain to get a better shot was the wrong thing to do.” • Making people cry for a better shot. Ethical Standards • Documentary media that is independent is “essential to democracy” • Trust between audience and subject • No right of review for subject • Accuracy, Fairness, and Obedience to the law Break Film – Supersize Me (2004) • http://www.lovefilm.com/film/Super-Size-Me/30209/ • Part of trend in 2000s for “personality led” documentary – like Yes Men (2003, 2008); Bowling for Columbine (2003) etc. • Ethical questions: is Spurlocks core argument fair? What is his point of view? Does he make implicit or explicit criticisms of any groups of people? • Modes: mix of performative and expository modes… – The subject of the film IS the filmmaker, but he is also – Social issues embedded in the frame.