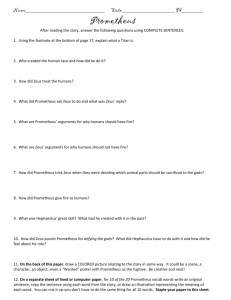

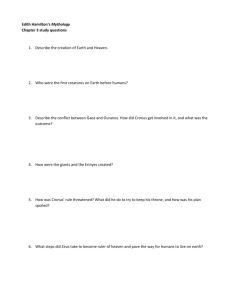

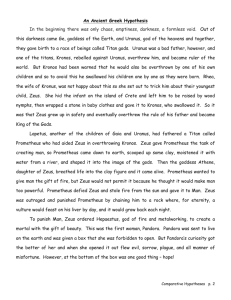

The Myth of Prometheus

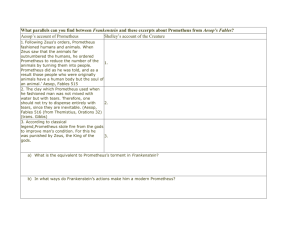

advertisement