presentation file (click here)

advertisement

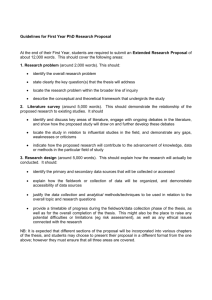

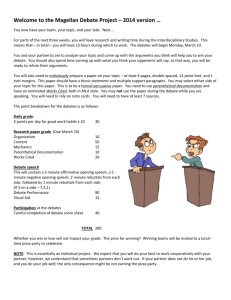

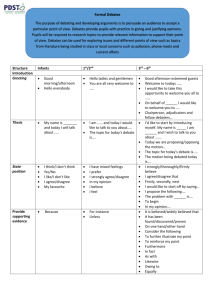

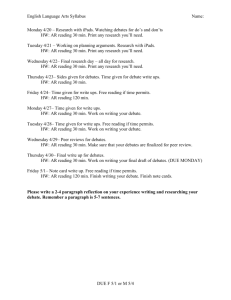

Better Writing through Big Debates Professional Development Workshop January 26-27, 2015 www.rossdunbar.com Why use debates in the classroom? Why use “big debates”? They’re fun, student-centered, engage all students in critical thinking, lead to better evidence-based writing Common Core State Standards for Michigan, 6-12 Literacy in ELA, History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects Writing CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.11-12.1 Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts, using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence. Redesigned SAT for 2016 Command of Evidence: When students take the Evidence-Based Reading and Writing and Essay sections of the redesigned SAT, they’ll be asked to demonstrate their ability to interpret, synthesize, and use evidence found in a wide range of sources. These include informational graphics and multi-paragraph passages excerpted from literature and literary nonfiction; texts in the humanities, science, history, and social studies. What courses or subjects would debates work well in? Are there any that debates would not work in? Why? Who can use big debates? Teachers across all subjects and disciplines can implement big debates around any of the following: inquiry-based learning; critical thinking tasks where there is more than one claim (thesis) that can be supported with relevant evidence; claim-evidence-reasoning based activities; in-depth reading tasks using complex texts and sources; persuasive, argumentative, or analytical writing tasks; and student-centered learning that requires students to provide relevant and sufficient evidence and valid reasoning to support their viewpoints/assertions. What is one example of an inquiry, activity, topic, task, or discussion from a course that you teach that requires students to defend a claim or thesis with evidence? Examples from social studies courses AP U.S. History (APUSH): To what extent is it justified to characterize the industrial leaders of the era 1865-1900 as either “captains of industry” or “robber barons”? (Ch. 19) [What’s the correct answer?] World History & Geography: Which was the best organized empire that connected across the Silk Roads: the Roman empire or the Han Dynasty? (Ch. 6 &7) [What’s the correct answer?] AP Macroeconomics: Support, refute or modify the following statement: “Government spending should be reduced during normal business cycles (i.e. except during emergencies).” (Ch. 19&21) [What’s the correct answer?] What things might make us uncomfortable as teachers in using this approach in the classroom? How might this approach increase student motivation, especially for evidence-based writing? Which reading and writing assignment would be more interesting to you? Read Chapter 12 on “Empires in East Asia” and answer the questions at the end of the chapter. Read Chapter 12 and create an evidence flowchart to defend your thesis on the following: Which society had the most effective governmental structure: the Tang & Song Dynasty, the Mongol Empire, or Feudal Japan? Why evidence-based writing is so important Traditional in-class tasks and homework (e.g. read textbook and answer questions at end of chapter) are replaced by inquiry tasks such as evidence flowcharts that require students to use critical thinking, grapple with competing evidence, and construct meaning and claims on their own. Students must articulate a clear thesis, explain and cite relevant and sufficient evidence, and provide valid reasoning. In-class tasks and homework become much more meaningful, challenging, and fun while strengthening essential writing skills that are required for success in college and the workplace. What is the most important step to ensure a successful debate and good evidencebased writing by all students? Step 1: Pre-Writing/Planning Lots of pre-writing and planning: Evidence-flowcharts from textbook readings Primary sources, secondary sources, and other Web-based sources (provided or researched) Written preparation prior to big debate (can lead to formal essay): Opening Statements (Introduction) Claim-Evidence-Reasoning Paragraphs (Body Paragraphs: Supporting Argument Paragraphs and Refute Opposing Argument Paragraphs) Closing Statements (Conclusion) Evidence Flowchart & Student Samples Evidence Flowchart & Student Samples Evidence Flowchart & Student Samples Step 2: The Debate Setup classroom, divide into teams (2-4 teams depending on how many theses/claims there are), and divide whiteboard for written comments. Teacher manages time, issues “strikes” for rules broken, and facilitates the following: Opening Statements (no questions) Each team given “the floor” to present evidence and to refute opposing claims; switch every 5-8 minutes Judges can fire off questions at any time Closing Statements (no questions) Judges vote on which team did a better job presenting relevant and sufficient evidence and valid reasoning to support its thesis in the debate Teacher can also recognize individual students as “best debaters” for that debate and post in-class What challenges might teachers face trying to facilitate debates in the classroom? Step 3: The Rules No interruptions: must “have the floor” or raise hand and wait to be called on by teacher. No talking on sides (teams can whisper to share ideas). No rude comments “Three strikes” leads to loss of all participation points New voices always go first “Three-before-me” when team has floor Face judges when making all arguments (except during “face-offs”) All students must participate: make an argument, ask question, or write comment or question on board Sample video clips from three different classes & subjects (played from iPhoto) * Opening Statements: 552, 554, 573, 574, 594, 595 * Teams given “the floor”: 555, 558 * “Strikes” for breaking rules: 553, 580, 587 * Analysis of textbook evidence: 556, 541, 557, 576, 599, 607 * Comparing textbook claims to primary sources: 592 * Challenging the evidence of others: 542, 566, 584, 598, 606 * Face-offs: 543, 609 * Judges asking questions: 544, 586, 593, 608 * New voices first: 567, 579, 600 * In-class articles read & documentaries: 559, 591 * Linking to Web-based sources & current events: 561, 589, 601, 560 * Written comments on board: 562, 564, 569, 570, 597 * Analysis of primary documents: 575. 577, 580, 596, 604 What kinds of follow-up and extended writing tasks and assignments could be used after a debate? Step 4: Follow-up Writing Follow-up written assignments can include: Revisions of written preparation based on debate Additional evidence-based writing tasks using additional sources Persuasive essay assigned that extends thesis Extended responses and essays on assessments Grading rubrics for evidence-based writing: Common Core State Standards for Michigan Smarter Balanced assessment rubrics Additional rubrics at AnalyticalWriting.org Student samples of follow up Grading Rubrics Common Core State Standards & Smarter Balanced; AP College Board The Results? Stronger evidence-based writing skills Improved willingness and enthusiasm in students for evidence-based writing and revising based on debates More in-depth analysis of complex texts and sources Students feel more challenged and are more engaged in their courses Increased student growth in Common Core State Standards for Writing in History/Social Studies, and in all subjects Students are better prepared for the demands of college and the workplace Big Debate in Teams (with workshop teachers) Support, Refute, or Modify the following statement: “Extra credit should not be offered in any high school courses.”