Opioids Part 2

Pharmacology of Opioids,

Assessment and Management

of Opioid Dependence

© 2009 University of Sydney

Treating James ….

• James is a 29 yr man with >10 yr Hx heroin & other drug

use

• Presents to ED with abscess in arm, pyrexia, heart murmur

• Injects heroin 2-3 times a day for past 15 months

• Works part time. ‘Deals to friends’ to support habit.

• Girlfriend started using heroin 2 years ago. She is 5

months pregnant & now infrequently uses heroin.

• In treatment 4 times before …

– Relapsed within days after each of 3 detoxes

– Stopped using for 3/12 in rehab, but relapsed on return

to community

• Would like to stop using … fed up & desperate

• Needs admission for Ix endocarditis

Learning Objectives

To be able to:

• Describe the pharmacology of opioids

• Assess the presence of dependence on

heroin or other opioids

• Discuss the role of different treatment

options

• Describe the management of opioid

withdrawal

Overview of presentation

• Heroin and other opioids

–

–

–

–

–

Opioid pharmacology

Opioid effects and withdrawal

Overdose

Patterns of use

Features of dependence

• Assessment

• Treatment approaches

– Detoxification

– Post-detoxification responses

– Substitution treatment: methadone,

buprenorphine, prescribed heroin, LAAM

• Selecting treatment: evidence-based practice

What is heroin?

Di-acetylmorphine

• Semi-synthetic opiate, derived from opium

poppy

• Vast majority of effects = morphine

• In Australia

– Most from South East Asia

– Water soluble for injecting

– >$300 /‘gram’, 10-20% purity

Agonists, partial

agonists, antagonists

•

•

•

Opioids produce their effect by

acting at the opioid receptors in

the nervous system

– -opioid receptor most

important

Agonists

– bind to the receptor and

stimulate physiological

activity

Partial agonists

– bind to the receptor but do

not produce maximum

stimulation

Antagonists

– have no intrinsic

pharmacological effect, but

bind to the receptor and can

block the action of an

agonist

100

Full Agonists: Heroin, morphine,

methadone, codeine

Size of Opiate Agonist Effect.

.

•

0

Threshold for respiratory

depression

Partial Agonists: Buprenorphine

Antagonists: Naltrexone, naloxone

Drug Dose

Lintzeris, N (2008). Unpublished data.

Reprinted with permission.

Opioid effects & withdrawal

Opioid effects

•

•

•

•

•

•

Analgesia

Sedation

Euphoria

Pinpoint pupils

Low BP, PR, RR

Dry skin, mouth,

urine

• Constipation,

bowel action

• Nausea, vomiting

Opioid withdrawal

•

•

•

•

•

Increased pain

Agitation, poor sleep

Dysphoria

Dilated pupils

Increased BP, PR,

RR

• Sweaty, urine

• Diarrhoea, abdo

cramps

• Nausea, vomiting

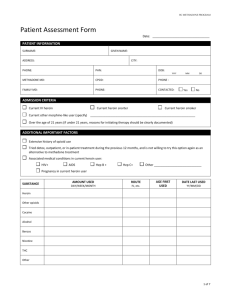

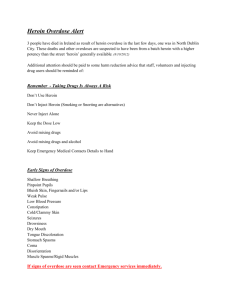

Opioid Overdose

• Signs

– Major feature - respiratory depression (slow

deep respiration 2-7/min) - risk of death

– Pinpoint pupils (but may be dilated if brain

damage occurred)

– Low BP, PR

– Low BT, skin cool, clammy

– Stuporose/comatose

• Treatment

– Reversal with naloxone (short-acting opioid

antagonist)

Source: NSW Department of Health (2007) NSW Drug and Alcohol Withdrawal Clinical Practice Guidelines

Patterns of Heroin Use

• The experimental user

• The 'recreational' or occasional user

– May or may not be associated with harms

(overdose, infections, other health risks, legal

complications)

• The dependent user

– Degrees of severity

– Severe dependence characterised by a

protracted course with multiple remissions

and relapses

Dependence (DSM IV-TR)

3 occurring at any time in the same 12 month period:

1. Tolerance

2.

Withdrawal

3.

Opioids taken in larger amounts or longer than

intended.

4.

Persistent desire or unsuccessful attempts to cut down

or control use.

5.

A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to

obtain opioids, use opioids, or recover from their

effects.

6.

Important social, occupational, or recreational activities

are given up or reduced because of opioid use.

7.

Opioid use is continued despite knowledge of harms

caused or exacerbated by opioids.

Factors affecting drug abuse

& dependence

• Drug

• User

• Environment

Drug

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Pharmacological effects

Onset of action

Duration of action

Route of administration

Purity

Availability

Cost

User

• Genetic predisposition or protection

• Expectancy of the effects

• Personality

– Impulsiveness, risk-taking, sensation

seeking

• Psychosocial

– Poor coping skills, low self-esteem,

history of psychological trauma

• Psychiatric co-morbidity

– Anxiety, depression, psychosis

Environment

• Family factors

– Attitudes towards substance use, parenting

skills

• Peer factors

– Attitudes towards substance use; role models

• Social factors

– School and neighbourhood attitudes towards

substance use; education; employment

status; socio-economic status; opportunities

for recreational activities; crime

‘Natural history’ of heroin

dependence

• Chronic, relapsing – remitting condition

– Usually starts several years after 1st heroin use

– 2 – 5 % remission rate per annum

• 1 – 2 % mortality rate per annum

– >10 x greater than age, gender matched non-users

– Overdose, liver disease (HCV, HBV), HIV, trauma

• 10 year outcomes (treatment seekers):

– 40 – 50% still using / imprisoned

– 30 – 40% abstinent

– 10 – 20% dead

• Most stop heroin use by late 30s to 40s.

Natural history

40 year follow-up study

Hser et al, 2001, Arch Gen Psychiatry, 58(5): 503-508, © 2001 American Medical Association.

Reprinted with permission.

Assessment

Role of assessment

Assessment serves two key functions:

• To ascertain valid information in order to

identify the most suitable management

plan;

• To engage the patient in the treatment

process

– Establishing rapport with the patient

– Facilitating treatment plans

Key features of the

assessment

• Presenting problem

• Drug use (include all drug classes)

– Quantity – frequency – route of administration

– Duration of use – when & amount last used

• Severity of dependence

– Withdrawal, tolerance, capacity to control use

• Drug related harms & risk practices

• Other conditions impacting upon treatment

– Medical / psychiatric / social

• Patient goals / expectancy

Conducting assessments

• History

• Examination

– Features of intoxication / withdrawal

– Evidence of drug use (e.g. injecting sites)

– Evidence of drug related harm (infections,

liver, heart murmurs)

• Investigations

– Urine drug screen

– Viral serology & LFTs

Evidence of drug use

Track marks provide

evidence for IDU and

last occasion of use

Stages of change model

(Prochaska & Di Clemente)

Pre-contemplation: People do not have major concerns

regarding their drug use and are not interested in

changing behaviour

Contemplation: People aware that there are both

benefits and problems arising from their drug use,

and are weighing up whether or not to make changes

- or what those changes should be

Action: People are implementing strategies in order to

change

Maintenance: holding onto the behaviour changes

Relapse: can be volitional, or triggered by physical,

emotional, social factors

Prochaska, JO et al (1985) Addict Behav, 10(4): 395-406.

ACTION

PREPARATION

MAINTENANCE

CONTEMPLATION

RELAPSE

• Some authors recognise a preparation stage before

the action stage

• In this diagram the pre-contemplation stage is merged

with relapse

Proude, E (2009), unpublished data

Treatment Options

Treatment pathways for

dependent heroin users

Dependent Heroin

User

Detox

Substitution

Maintenance

Treatment

Detox from

maintenance

treatment

Post Detox Treatment Options

Opioid withdrawal

syndrome

•

•

•

•

•

Increased pain

Agitation, poor sleep

Dysphoria

Dilated pupils

Increased BP, PR,

RR

• Sweaty, urine

• Diarrhoea, abdo

cramps

• Nausea, vomiting

Image source: NSW Department of Health (2007) NSW Drug and Alcohol Withdrawal Clinical Practice Guidelines

Objectives of detoxification

• Detox is not a ‘cure’ for heroin dependence

– Most heroin users relapse after withdrawal

– Need long-term treatment to achieve longterm changes

• Short-term intervention that aims to:

– Interrupt a pattern of heavy & regular drug

use

– Alleviate withdrawal discomfort

– Prevent complications of withdrawal

– Facilitate post-withdrawal treatment linkages

Components of detox program

• Assessment & client-treatment matching

• Supportive care

– ‘safe’ environment (inpatient / outpatient)

– patient information

– supportive counselling

– regular monitoring

• Medication

• Post-withdrawal linkages

Medication approaches for

detox

• Symptomatic medications

– Clonidine

– BZDs, NSAIDS, antiemetics, antidiarrhoeal agents,

etc.

• Methadone or buprenorphine

– Reducing doses over days / weeks

– Minimises severity of withdrawal symptoms

– Buprenorphine increasingly used internationally

• Antagonist assisted (‘rapid detox’)

– Uses naloxone / naltrexone as prelude to longer term

antagonist treatment

Heroin withdrawal

Unmedicated

Lofexidine / clonidine

Methadone (7 day)

Withdrawal severity

Buprenorphine (7 day)

Rapid detox' (naltrexone)

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Day

Lintzeris, N (2008) unpublished data. Reprinted with permission.

8

9

10

Short buprenorphine detox

regimes

Inpatient

Outpatient

Day

Proposed

regime

Upper &

lower limits

1

8 mg

2

Day

Proposed

regime

Daily

dose

4 to 8mg

1

4mg BD

8 mg

12 mg

4 to 12mg

2

4mg BD

8 mg

3

10 mg

4 to 16mg

3

6 mg

4

8 mg

2 to 12mg

4mg mane

2mg nocte

5

4 mg

0 to 8mg

4

2mg BD

4 mg

6

-

0 to 4mg

5

2 mg mane

2 mg

7

-

0 to 2mg

6

No dose

Lintzeris, N et al (2006) National clinical guidelines and procedures for the use of

buprenorphine in the treatment of opioid dependence.

…but beware of limitations

of detox…

RCT BPN Maintenance vs Detox

• 40 subjects randomised to

– 1 week detox / 1 yr

maintenance

– All provided counselling for

1 year

• Heroin use

– Detox = all relapsed

– Maintenance=75% Opiate ()ve UDS

• Mortality (p=0.015)

– Detox 4/20 (20%)

– Maintenance 0/20

Reprinted from The Lancet. Kakko et al (2003) Lancet,

361:662-8 with permission from Elsevier.

RCT Methadone maintenance vs

gradual detox

• N=179 randomised to

– 1 year methadone

maintenance, or

– 6 months gradual

reduction + intensive

psychosocial

• Results: MMT had

significantly

–

–

–

–

Better treatment retention

Less heroin use

Fewer HIV risk practices

Fewer legal problems

Sees et al, 2000 JAMA, 283:1303. Copyright © 2000 American Medical

Association. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

Key points about detox

• Do not expect ‘cures’ from detox programs

• Short term treatment usually = short term changes

• Medication only one aspect to good detox

• BPN optimal detox medication & increases postdetox options

NB: Detox is not a treatment for dependence but

rather a pre-treatment phase for some more

comprehensive treatments.

Treatment pathways for

dependent heroin users

Dependent Heroin

User

Detox

Substitution

Maintenance

Treatment

Detox from

maintenance

treatment

Post Detox Treatment Options

Post-withdrawal interventions

• Counselling

– Various models (supportive, behavioural,

dynamic)

– Cochrane review: limited efficacy of

outpatient counselling alone

• Residential rehabilitation (long term > 3/12)

• Self – help (Narcotics Anonymous)

• Naltrexone

– Opioid antagonist that blocks effects of heroin

use

– Effective for those who take it, but high drop

out rate (< 10% retention at 6 months)

Naltrexone : clinical issues

• Induction

–

–

–

–

>7 days after last heroin use,

>10 days after last methadone use,

1-5 days after last BPN use

Naloxone challenge test recommended (not postBPN)

• Maintenance

– Daily dosing of 25 to 50 mg per day

– Recommended duration of 6 to 12 months

• Cessation

– ? Increased sensitivity & risk of OD with opiates

• Interest in development of long-acting NTX (e.g.

depot injection, implant) to overcome problems of

poor adherence

Treatment pathways for

dependent heroin users

Dependent Heroin

User

Detox

Substitution

Maintenance

Treatment

Detox from

maintenance

treatment

Post Detox Treatment Options

Substitution treatment

• Provision of a long-acting prescribed opioid enables

patient to cease / reduce heroin use & related

behaviors

• Long term approach: opportunity for client to

distance themselves from drug-using lifestyle

• Combines medication with psychosocial services

• Medication options: methadone & buprenorphine

• Other medication options (not approved in

Australia): prescribed heroin, LAAM.

Methadone stabilisation

Reprinted from The Lancet.

Haber, PS et al (2009) “Management of injecting drug users admitted to hospital” Lancet, 374(9697):1284-93.

© 2009 with permission from Elsevier.

Principles of effective

treatment

•

•

•

•

Long duration of treatment

Adequate dose of medication

Quality of therapeutic relationship

Psycho-social supports for the patient

– Regular review, supervision & monitoring

– Participation in counselling

– Environment, family, friends, employment

Bio-psycho-social model for chronic condition

Does substitution treatment

work?

Heroin use

Despite considerable variation between programs,

almost all patients reduce heroin use

~ 1/2 of patients stop using heroin

~ 1/3 of patients use heroin infrequently

~ 1/6 of patients continue to use heroin

frequently

Does substitution treatment

work?

• Mortality rates

– Heroin users not in treatment = 1 - 2% per

annum (p.a.)

– Methadone maintenance treatment = 0.5 to 0.75

% p.a.

• HIV transmission

– Lower risk practices than users not in treatment

(placebo or wait list controls)

– Lower rates of HIV transmission

• Criminality

– Reduced crime in most patients after treatment

Methadone

•

•

•

•

Full agonist at - opioid receptor

Onset 30 - 60 min after dose, Peak after ~ 2 - 6 hrs

Long-acting: t1/2= 24-30 hrs: one dose / day

Opioid toxicity with too much methadone: sedation,

respiratory depression, death

– 1 dose of 20-40mg can kill child

– Repeated doses of 30–40mg can kill an adult

(opiate naïve)

– 1 dose of 70mg can kill an adult (opiate naïve)

• Widespread diversion & methadone related deaths

where no supervision (e.g. UK)

• Daily supervised dispensing at clinics / pharmacies

Henry-Edwards et al (2003) Clinical Guidelines and Procedures for the Use of

Methadone in the Maintenance Treatment of Opioid Dependence.

Principles of methadone

dosing

• Induction

– Require slow induction (‘start low & go slow’)

– 20-30mg / day & increase dose by 5-10mg every

3 days until reach target dose (over 2-6 weeks)

• Maintenance

– Doses of 20 – 40mg prevent opiate withdrawal

– Doses >60mg most effective in reducing heroin

use

• Withdrawal

– Gradual dose reductions (at rate of 10mg /

month)

Henry-Edwards et al (2003) Clinical Guidelines and Procedures for the Use of Methadone

in the Maintenance Treatment of Opioid Dependence.

Buprenorphine

• Partial agonist at the opioid receptor

- Low intrinsic activity only partially

activates receptors

• High affinity for the receptor

- Binds more tightly to receptors than

other opioids

- Developed in 1980s as analgesic

Classification of Opioids

100

Size of Opiate Agonist Effect.

.

Full Agonists: Heroin, morphine,

methadone, codeine

0

Threshold for respiratory

depression

Partial Agonists: Buprenorphine

Antagonists: Naltrexone, naloxone

Drug Dose

Lintzeris, N (2008). Unpublished data. Reprinted with permission.

Safety Aspects of BPN

• Less risk of overdose c/w full opiate

agonists

– Less respiratory depression & sedation than

methadone

– BPN ‘tolerated’ by individuals with low levels

of opiate dependence

• Potential concerns re: safety

– BPN related deaths reported in combination

with other sedatives (EtOH, BZDs) … BUT

less of a concern than other opiates (e.g.

methadone, heroin)

Clinical Pharmacology

• Sublingual tablets

– 0.4, 2 & 8 mg tablets available

– 3 to 10 minutes to dissolve

• Time course

– Onset: 30–60 min, peak: 1–4 hours

– Duration of action dose-related (1 dose / day)

• Side effects

– Typical for opioid class: less sedating than

methadone

• Withdrawal syndrome

– Milder than full agonists

Lintzeris et al (2006) National clinical guidelines and procedures for the use of buprenorphine in

treatment of opioid dependence.

Overview BPN Doses

Induction

• Delay first dose of BPN until early opiate withdrawal

• Commence 4 to 8 mg daily

• Frequent & rapid dose increases possible (by 2 to

8mg/day)

Maintenance

• Daily doses: 8 – 16mg (max 32mg) required initially

• Alternate day dosing possible for many clients

Withdrawal

• More rapid dose reductions possible than

methadone

(e.g. 2 – 4 mg / week usually well tolerated)

Lintzeris et al (2006) National clinical guidelines and procedures for the use of buprenorphine in

treatment of opioid dependence.

Buprenorphine-naloxone tablet

(Suboxone®)

• Sublingual tablet in 4:1 ratio (BPN:NLX)

• Naloxone (antagonist) poorly absorbed

sublingually & inactive

• Naloxone produces antagonist (withdrawal)

effects if tablet injected by heroin user

• Enables take-away doses with greater

convenience for patients & less risk of

tablet misuse

When should we stop

substitution treatment?

• Chronic condition needs long term treatment

– Premature cessation of treatment usually results in

relapse to dependent heroin use

• Consider ending treatment when:

–

–

–

–

No illicit drug use for months / years

Stable social environment

Stable medical / psychiatric conditions

Patient ‘has a life’ that does not revolve around

drugs

– Patient informed consent

• When do we stop anti

convulsants/antidepressants?

Common objections to

substitution treatment

• Swapping ‘one drug for another’

• Prolongs ‘addiction career’

• Methadone-related deaths (e.g. accidental

deaths in children)

• Cannot treat a bio-psycho-social condition

just with drugs

• Giving up on the ‘war on drugs’

• Form of ‘social control’ over minorities /

marginalised groups

Heroin Maintenance

• A controversial treatment approach

• Was limited to Britain until 1990

• Currently licensed and available for

prescription in several European

countries

• Usually prescribed IV injections of 300500mg/day in 3 divided doses

• Uncommon but serious side effects

– Seizures and respiratory depression

immediately following injection

Lintzeris N (2009) CNS Drugs, 23(6):463-476.

Heroin Maintenance (cont.)

• Effectiveness is comparable to methadone in

retaining patients in treatment and improving

health

• More effective than methadone in reducing

additional heroin use

• More expensive to deliver than methadone but

significant savings can be made in the criminal

justice sector

• The main rationale for heroin maintenance is

treatment of refractory patients who do not

respond to methadone or buprenorphine

treatment delivered under optimal conditions

Lintzeris N (2009) CNS Drugs, 23(6):463-476.

LAAM

• Levo-alpha-acetylmethadol (LAAM) is a

long acting congener of methadone.

• Two active metabolites are responsible

for most of the effect of LAAM

– nor-LAAM (half-life >30 hours)

– dinor-LAAM (half-life >100 hours)

• The parent drug (also active) and the

metabolites all have selective affinity for

the µ-opioid receptor

White JM and Lopatko OV (2007) Expert Opin Pharmacother., 8(1):1-11. Review

LAAM

• Administered as an oral solution

• LAAM can be administered every second day, or

3 times/week.

• At least as effective as methadone in opioid

maintenance treatment

• The parent drug was found to prolong QT interval

(a potential cause in cases of Torsades de

Pointes) and was subsequently withdrawn by the

manufacturer.

• There is the potential for the metabolite norLAAM to be used therapeutically, and for the reintroduction of LAAM with careful monitoring.

White JM and Lopatko OV (2007) Expert Opin Pharmacother., 8(1):1-11. Review

Selecting Treatment

Approaches

Selecting treatment modalities:

Evidence-based medicine

• Patient circumstances

– Patient goals & expectations of treatment

– Past history of what has worked before

• Available resources

– Treatment services available

– Cost of different treatment approaches

• Evidence regarding safety & effectiveness

Comparing outcomes & costs

Heroin use /

retention

Detox

<5% long term

abstinence

Mortality

Cost

? increase / no $1000 / week

change

3 – 4 fold

reduction

Maintenance

50% retention 1yr

25% no heroin use 1yr

Naltrexone

5-10% retention 1 yr. ? increase / no $4,000/year

change

Most drop outs relapse

Therapeutic

community

Few stay in Rx unless

++ motivation /

pressure

?

$10-15,000

Good retention rates

increase on

release

$40-70,000

Prison

Lintzeris, N (2008). Unpublished data. Reprinted with permission.

$3000 / year

Retention in treatment:

methadone, buprenorphine & LAAM vs.

naltrexone

Mattick RP et al. (2001) “National Evaluation of Pharmacotherapies for Opioid Dependence (NEPOD):

Report of Results and Recommendations”. National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, Sydney.

© Commonwealth of Australia reproduced by permission.

‘Public health’ vs ‘Treatment’

models

The balance between

• Services oriented to ‘public health’ outcomes

– Increased numbers in treatment, general

reductions in drug use, mortality, HIV

transmission

– Low intensity & less expensive services

• Services oriented to maximise ‘treatment’

outcomes

– Comprehensive programs, more expensive,

fewer numbers

– Oriented towards rehabilitation

– Manage medical and psychiatric comorbidity

Conclusions

• Heroin dependence is a long term condition

• Long term conditions (e.g. heroin dependence) usually

require long-term interventions

• Public health response requires treatment approaches

that can be disseminated effectively & inexpensively

• Most treatment approaches work, as long as patients

remain in treatment

– Substitution treatment has greatest retention rates

for most patients & reduces harms associated with

heroin use

– Need range of treatment interventions to suit

different patients

Treating James ….

•

•

•

•

•

James is a 29 year old man with >10 yr history heroin use

Injects heroin 2-3 times a day

Part time-work & deals to support habit

Pregnant girlfriend using heroin infrequently

In treatment 4 times before …

– Relapsed after detox & rehab

• Presents with infected arm & ?endocarditis.

• Wants to stop using. Needs admission

• ………. detox … likely relapse

• ………. rehab … working & girlfriend pregnant

• .……… initiate BPN whilst in hospital, stabilise medical

condition & review treatment plans

Contributors

• Associate Professor Nicholas Lintzeris

Drug Health Services, SSWAHS

Central Clinical School, University of Sydney

• Dr Olga Lopatko

University of Sydney

All images used with permission, where applicable