An analysis of Kant's argument against the Cartesian skeptic in his

advertisement

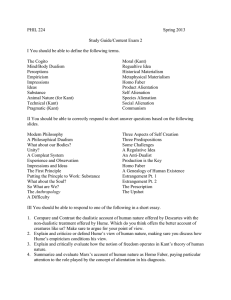

An analysis of Kant’s argument against the Cartesian skeptic in his ‘Refutation of Idealism” Preface: Throughout the semester the burning question seemed to be, how do I know my inner experiences correspond to the object that is external to me? After reading Descartes Meditations I could not help but wonder whether the premise Cogitio Ergo Sum should be the starting point of coming to know objects outside of the self. Epistemologically speaking, what is the ‘right’ starting point of our departure to know objects? These questions lead me to try and find a path to certainty, one of which I believe is possible by using Kant’s approach of how we know objects. The Cartesian idealist is bound to start with consciousness but the assumption is that we only know those objects that are represented to us to consciousness, that is, we are affected by the ontologically distinct object outside of ourselves but can never really know whether that distinct object matches up with our ‘idea’ of it. The Kantian on the other hand seems to assume that to understand the inner experience one must presuppose the external object as determining that inner object. This is a move that turns the Cartesian idealist around and argues the other way, starting with the external object and ending with the inner experience of that external object. Though the literature on Kant is overwhelming, I will just focus on his ‘Refutation of Idealism’1 (hereafter RI) in the B edition (second edition) while heavily relying on the ‘Analogies of Experience’ 2(AE) and Henry Allison’s interpretation of the text3. The translation of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason (CPR) is by Norman Kemp Smith. The ‘Analogies’ are important as they explain the notion of substance, time as determined/the persistent thing and the coexistent of objects in time. Time and space play a key role in Kant’s argument, along with his notion of substance. The notion of causality is also vitality important and will be discussed in the course of the lecture. The first part of the this lecture will endeavor to look at the argument itself and outline the premises in the order found in the CPR , more specifically in the RI. Once the argument itself is laid out we will walk through each premise, elucidating any technical terms that we may find to help us understand exactly how Kant is going to prove the existence of external objects. 4 1 Kant, Immanuel . Critique of Pure Reason . New York: Palgrave Macmillian , 2003. Ibid. 3 Allison, Henry. Kant's Transcendental Idealism. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983. 2 4 Due to the constraints of the lecture, I am limited to only focusing on the argument itself and not giving a background to Kant’s philosophy. When writing, I found myself unconsciously explaining every single Kantian philosophical concept (concept not in the Kantian sense) without even touching the argument itself. If I want to hit the heart of the skeptic I need to just analyze the argument itself rather than giving a lecture on Kant’s idea of the self or of the categories of the understanding. The approach I am going to be taking is one of specificity and requires some idea of Kant’s philosophy. The second part of the lecture is to analyze the propositions given in the argument, giving substantive reasons as to why Kant said what he did and interpret what he said in light of refuting the ‘problematic Idealist’, which in this case is the Cartesian idealist. Lastly I propose to flesh out some of the implications regarding answering the skeptic when it comes to being certain about external objects corresponding to the inner states we are aware of. I am aware that Kant’s argument is not the only position or argument to refute the skeptic but rather it is an option that one may take. I am interested, not in dogmatically asserting that this is the only way but rather I want the reader to think for herself through want Kant has to say in how one comes to know objects are real. Part One: To start let me quote Kant and his Thesis in B275-76: “The mere, but empirically determined, consciousness of my own existence proves the existence of objects in space outside me.” His argument is as follows: (1) “I am conscious of my own existence as determined in time. (2) All determination of time presupposes something permanent in perception. (3) This permanent cannot, however, be something in me, since it is only through this permanent that my existence in time can itself be determined. (4) Thus perception of this permanent is possible through a thing outside me and not through the mere representation of a thing outside me; and consequently the determination of my existence in time is possible only through the existence of actual things which I perceive outside me.(5)Now consciousness [of my existence] in time is necessarily bound up with consciousness of the [condition of the] possibility of this timedetermination; and is therefore necessarily bound up with the existence of things outside me, as the condition of the time-determination” (B 276). To understand the aim of the argument we should take a look at B274-75, where Kant explains who he is refuting and why. He starts out by explaining what Idealism is but more specifically the various brands of idealism and how his brand fits in. He calls the idealism of Descartes problematic idealism, which starts with the indubitable assertion of ‘I am’ and proceeds to argue to external objects from the empirical claim of ‘I am’. He mentions Berkeley and his dogmatic idealism but only in passing, the main goal for Kant is to refute the problematic idealist, as he makes clear in the last paragraph, “The required proof must, therefore, show that we have experience, and not merely imagination of outer things; and this, it would seem, cannot be achieved save by proof that even our inner experience, which for Descartes is indubitable, is possible only on the assumption of outer experience” (B275 added italics for emphasis). In essence the aim of Kant is to show or demonstrate that we do know outer things and not just a figment of our imagination. Descartes would grant that immediate experience of the inner objects are most ‘clear and distinct’ but does this justify our believing that the objects that we experience match up with the external objects of experience? Of course not, since we cannot ‘get beyond’ as it were, the representations of the object which affects our senses. The object is given to consciousness and thus cannot know what this object is apart from consciousness, it would not be possible, or so it is in a Cartesian framework. To overcome the ego centric predicament, Kant proposes that outer experience must be presupposed for inner experiences to be possible. In other words, for me to even be aware of the object in my inner experience, the object outside must be assumed. The reason why the outer object must be assumed is based on Kant’s transcendental idealism and his view of space and time. The object is necessarily subject to conditions which make the inner experience possible and thus the object must be spatial since it is a condition for experience. We will look into this further into the lecture but for now it is sufficient to understand that Kant aims at undercutting the Cartesian by his understanding of outer objects as a condition for inner experience. Premise 1: “I am conscious of my own existence in time” (B276). The ‘inner experience’ is the faculty by which all things are ‘seen’. This consciousness is empirical in the sense that it is available for introspection and given by intuition. Using this framework of consciousness we can see that for Kant the inner experience is only possible with outer objects to supply it with content. Returning to B275 Kant says something revealing, distinguishing himself from Descartes, “The required proof must, therefore, show that we have experience, and not merely imagination of outer things; and this, it would seem, cannot be achieved save by proof that even our inner experience, which for Descartes is indubitable, is possible only on the assumption of outer experience” (B275). We must remember Kant throughout his CPR is concerned with the conditions of experience as such these conditions are epistemic in nature. The question is not the content of consciousness but rather the condition for subjective consciousness. Following Henry Allison and his analysis of Kant’s notion of consciousness he says “If the consciousness of one’s existence in time is equated with inner experience…it must consist in the mind’s knowledge of its own representations taken as “subjective objects…these “subjective objects” are experienced as they “exist objectively in time” 5 (Allison 1983, 298-309). 5 Allison, Henry. Kant's Transcendental Idealism. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983. If we understand Kant’s pure forms of intuition such as space and time6 we can understand what Allison means by “subjective objects” are experienced as they “exist objectively in time”. The “subjective objects” as determined in time, that is determined by the a priori necessary conditions of time and space we can then say without a doubt that the objects as subjective “exist objectively in time.” For something to exist in time is to exist in succession and not without order. Therefore, from what we have said about consciousness, it follows from Kant’s concept of space and time as necessary conditions for experience we can say that the objects given to the inner experience are only given by the objects that are determined by space and time. This then shows that we can say that there are bodies outside my inner experience since the body is spatial. Time is a key concept here since it involves the objects given to consciousness to be ordered in succession or it would be just raw sense data that is not synthesized with the a priori subjective forms of intuition.7 Premise 2: “All determination of time presupposes something permanent in perception” (B275). For something to be in time is for something to persist through time to account for the identity of the thing. What does it mean for something to be determined in time? To look for this answer I suggest we look in the First Analogy of Experience, which shows us the principle which Kant states, “In all change of appearances substance is permanent; its quantum in nature is neither increased nor diminished”(B224). The substance is that which is permanent, does Kant mean an Aristotelian notion of substance or a Cartesian notion of substance? Some scholars have found that Kant uses both in his writings but are in disagreement as to what exactly he means. Allison tends to see Kant not conflating the two notions of substance, drawn from Aristotle and Descartes but rather see’s Kant as modifying the traditional concept of substance by his “replacement of ontological independence with the physical property of independent mobility” (Allison 214). Not to do injustice to Allison I would like to explain what he means. First Kant understands substances as indeterminate like Aristotle To read more about Kant’s notion of space and time I would suggest reading his Transcendental Aesthetic in his CPR. In its most simplistic form, space if it is considered in relations with other objects we can only think of the object as spatial and without such ‘property’ (using property as if space is an object in the Newtonian sense) could such experience be impossible. Now considering space as an object can lead one to absurd conclusions. For example: Suppose one were to ask what is beyond the object space? Or what is under the object given to the senses that could determine the objects that we perceive? How could we perceive at all without space and time as being the subjective constitution of experience? Space and time for Kant are a priori conditions for experience, nothing can be thought or represented to inner experience without it being spatial or determined in time. 7 Intuition is given by Kant as “that through which is in immediate relation to them (objects), and to which all is thought as a means is directed. But intuition takes place only insofar as the object is given to us… Objects are given to us by means of sensibility” (added emphasis, B34). To understand intuition is to understand it as sensible intuition since this is the only way we can know objects. That objects are given only to be organized and arranged accordingly. 6 but differs in methodology, that is Kant understands substance in the transcendental sense. For example, we do not have an intuition or faculty by which we can grasp the positive content of the substance or the essence of the thing, the only access we have to even understanding is by thing in time and space. Therefore, for something to be determined in time is for something to be ordered outside of perception and thus we need substance to explain change of things. How do things come into being and out of being and yet still perceive causally and orderly? Only by appealing to substance as a condition for experience can we say to have experience of the thing. To understand something as coming in and out of existence is to understand order by contrasting that which inner experience testifies to. Premise 3: “This persisting thing, however, cannot be something in me, since my own existence in time can first be determined only through this persisting thing” (B275). Premise 31: “But this permanent cannot be an intuition in me. For all grounds of determination of my existence which are to be met with in me are representations; and as representations themselves require a permanent distinct from them, in relation to which their change, and so my existence in the time wherein they change, may be determined” (Preface to B pg.36). As we concluded about that the persistent thing is substance and underlies time, the persistent thing cannot be in oneself since one cannot determine ones existence except under the condition of time which is the persistent thing. Kant in his First Analogy explains the permanence as “the substratum of the empirical representation of time itself; in it alone is any determination of time possible. Permanence, as the abiding correlate of all existence of appearances, of all change, and of all concomitance, expresses time in general…Without the permanent there is therefore no time-relation. Now time cannot be perceived itself; the permanent in the appearances is therefore the substratum of all determination of time, and, as likewise follows, is also the condition of the possibility of all synthetic unity of perceptions, that is, experience” (B227 added emphasis). It is interesting how Kant accounts for the ‘real’ relations using time as permanence to substantiate his claim concerning the reality of objects apart from one’s representations. These categories of course are the a priori conditions of experience and one should note that intuition is the passive species of representation. In reference to the self being exempt from being the ground of the determination of one’s existence, for Kant the grounds cannot be himself and his own representations since to represent something is to determine it in time. All appearances whether inner or outer cannot be the grounds of determinations in time since something must order those appearances. The question remains, why do we need something persistent or permanent in perception to account for time-determination? What would experience look like without time and space? What is key here is the empirical is not the impressions thought of by David Hume but rather experience is a synthesis of appearances with the a priori forms of intuition, which forms the phenomena. The logical necessity of time and cause are not something we can perceive, since we have no faculty by which we can perceive them but rather are conditions for experience. Taking this into consideration, I will ask again, what does experience apart from the a priori conditions of space and time look like? By using the word look it leads us to absurdities. Does sense data bring us the permanent? According to Kant no it is that which is determined in time, which means to determine or limit that which is in time. To determine something is simply to give the boundaries of something or to give the shape to something that is indeterminate. A good example of this is found in Dina Emudts article The Refutation of Idealism and the Distinction Between Phenomena and Noumena8 and in this article he illustrates why it is that one needs something permanent in perception. He asks to do a thought experiment of two distinct ships both given in perception as crossing a river in time. Remember to determine something in time is to determine something that changes, following this line of reasoning we can see how we need the ship to persist in time to even make sense of perceiving it crossing the river. To determine that the ship is moving or is crossing the river is to determine the perception of it moving and we can take the ship as persisting through the changing of perceptions. Throughout the change we can say ‘the ship’ moved in a succession of events in perception and thus we can say that something persistent must be presupposed to make sense of relative permanence. Can something that is only relative persistent be called ‘real’ outside our representation of the object? It would seem not, since relative motion or relative permanence cannot account for all perception determined in time. Following Emudts argument he says, “It must be possible to determine all experiences in only one time. Therefore all experiences must be linked to one another according to the laws of causality and interaction, because these are the laws that determine something objectively in time…The crucial point is that this has to be something that persists through all changes we want to determine” (Emudts 173). Objectively is reached only if a thing absolutely persists in all time-determination. It follows from this idea that one must understand Kant and the substance he is proposing as seen from above, as matter in motion. The reason why the matter must be in motion is because outer intuition can intuit it as subjected under the necessary conditions of space and time or else the perception would be unintelligible and nonsense. 8 Emundts. "The Cambridge Companion to Kant's Critique of Pure Reason." The Refutation of Idealism and the Distinction between Phenomena and Noumena , Edited by Paul Guyer, 168-189. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010. Premise 4: “Thus perception of this permanent is possible only through a thing outside me and not through the mere representation of a thing outside me; and consequently the determination of my existence in time is possible only through the existence of actual things which I perceive outside me.” (B276). It follows from premise 31 that the permanent is not something ‘from within’ or inner intuition so what other canadites for this permenant thing is there? What about outer intuition? What is outer intuition? Again, he says “perception of this permanent is possible only through a thing outside me.” What does Kant mean by this ‘thing outside’ me? To intuit something outside oneself is to intuit under the form of space. The spatial qualities are established by virtue of Kant’s transcendental conditions of space and therefore one can say that the object is spatial but does this permit us to say that the object is ‘real’, in the metaphysical sense of being independent from perception for its existence? This conclusion in premise 4 seems only to say that the object must be spatial but what about objects of the imagination? How does Kant distinguish from the imagination and the things that are ‘really’ out there apart from consciousness? The mix up I believe is between the outer intuition of sensation and the outer intuition of imagination. Is there even such a thing as something being given to the imagination by another means other than intuiting it from sensation? It seems that the objects that we passively receive and intuit are done by means of the outer intuition. To clear up this distinction Kant tells us that, “It does not follow that every intuitive representation of outer things involves the existence of these things, for their representation can very well be the product merely of the imagination (as in dreams and delusions). Such representation is merely the reproduction of previous outer perceptions, which, as has been shown, are possible only through the reality of outer objects” (B279). Again Kant would say, for the possibility of having a dream or delusion requires a time when one intuited something from the outside. For the possibility of having content one must posit the reality of objects outside oneself. Premise 5: “Now consciousness [of my existence] in time is necessarily bound up with consciousness of the [condition of the] possibility of this time-determination; and is therefore necessarily bound up with the existence of things outside me, as the condition of the time-determination” (B 276). Remember to be conscious of one’s existence is to know only mediately by virtue of outer objects oneself. The latter is what distinguishes the transcendental idealist from a Cartesian one. We are immediately aware of outer objects since the outer objects are time-determined by the a prior conditions of space and time. Basically there are two aspects or two poles of experience, the consciousness of ones existence in time is necessary bound up with the conditions of the very experience of one’s self as existing. Hence the necessity derives itself from the categories of the understanding or the form which exists only in the mind. The necessity of this inextricable connection is not derived from experience since as we have seen with Hume, this leads to just impressions and ideas. The necessity is supplied and thus we can make sense of the world and its outer objects. We cannot know that which we cannot possibly know. The framework is important in understanding this key point. Concluding thoughts: To reiterate what has been said I think it would be necessary to elucidate some points, (1) Consciousness for Kant, the ‘I am’ is not exempt from being determined in time and thus one can intuit the I as an empirical thing. If one only can know oneself mediately than it would follow that one can only know oneself if outer objects are posited or assumed. (2) If one sees consciousness in the Kantian framework, transcendentally speaking, one can only understand objects as spatial and temporal. The conditions are placed upon the external objects as spatial and determined in time. Time itself cannot be determined since it is what lies behind the appearances and could be called, using a Kantian term, the thing-in-itself. Time though cannot be perceived as Kant says explicitly in B278, “Not only are we unable to perceive any determination of time save through change in outer relations (motion) relatively to the permanent in space…we have noting permanent on which, as intuition, we can base the concept of a substance, save only matter; and even this permanence is not obtained from outer experience” (B278). (3) The permanence we cannot perceive but only presuppose as a condition for experience, more specifically, time determined objects. We cannot say for instance that the category of substance, in the Aristotelian sense, can be grasped by some intellectual faculty, since for Kant we can never know the thing-in-itself. We cannot give it any positive properties rather we can only define in a negative fashion. For example we can say the thing-initself is that which we know not what (sounds Lockean to me.) (4) Empirically speaking I believe we can call Kant a empirical realist, in the sense that space and time are ‘real’ and that there are objects outside the mind that persist through time by virtue of the absolute persisting thing, which in Kant’s case would be the substratum of all experience as succession of events in time. The objects are ‘real’ in the sense that they are given as outer objects to inner experience and not the other way around. In a sense we have immediate experience of the outer objects and mediate experience of the inner objects. We can contrast and compare the inner and outer by virtue of the laws of causality outside of oneself. If one determines an object in time and that object is one’s own existence we can say that existence is not inferred but rather is immediate. To make an inference to outer objects is the very problem Kant is trying to refute. (5) In the end is it a convincing case against the Cartesian skeptic, with respect to the existence of outer objects apart from our inner experience? That is a question I will leave to the audience. Bibliography: Allison, Henry. Kant's Transcendental Idealism. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983. Emundts. "The Cambridge Companion to Kant's Critique of Pure Reason." The Refutation of Idealism and the Distinction between Phenomena and Noumena , Edited by Paul Guyer, 168-189. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010. Kant, Immanuel . Critique of Pure Reason . New York: Palgrave Macmillian , 2003.