kant's categorical imperative

advertisement

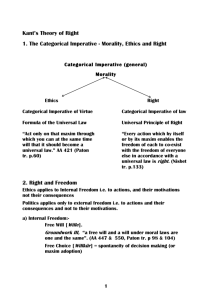

The Journey toward Moral Certainty Immanuel Kant, 1724-1804 Grounding/Groundwork for a Metaphysics of Morals, 1785 3 themes: 1. The Categorical Imperative 2. Rational Beings are Ends-In-Themselves 3. The Kingdom of Ends First you establish: does a person have “good will”? How? By looking at his or her intentions: Can they be said to involve a respect for a universal moral law? Such as, “this is the kind of thing everybody should do”? If yes, then the person has good will, and it “shines by its own light, like a jewel.” It is intrinsically valuable. Consequences of one’s actions are unimportant as long as one has good will. Kant would say, “I’m glad you asked.” First, a detour: Hypothetical imperatives: If I want X, then I must do Y. But if I don’t want X, I don’t have to do Y. So hypothetical imperatives are “conditional commands,” depending on the situation. They are not morally relevant. True moral commands, however, have no conditions; they are always valid, independent of situations and consequences. So: they are categorical. A categorical imperative = an absolute command. An example: the store owner’s four options. The Question: Should I cheat my customers? Yes, whenever I can get away with it. No, I might get caught and lose my store and go to jail. No, I like my customers too much to ever cheat them. No, it just wouldn’t be right! “Always act so that you can will that your maxim can become a universal law.” State your maxim (the principle for your action) 2. Universalize your maxim 3. Ask, Is that rational? If not, don’t do it. If yes, you may do it. Example: the man who wants to borrow money 1. For Kant, every rational being is an “autonomous lawmaker.” So won’t we end up with each person just setting their own rules? No, because Kant thinks reason is universal, and will always work the same way. If you use the categorical imperative, you will come to the same conclusion as everyone else using the same method. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. J.S. Mill: Kant claims that consequences don’t count, and yet he “universalizes the maxim.” isn’t that asking about consequences? Not all moral conflicts are between duty and desires. So how can the cat.imp. help if we have a conflict between duties? There is a loophole in the cat.imp.: If we make our maxim so specific that it only applies to ourselves when universalized, we can get away with anything. What exactly does Kant mean by rationality, and isn’t it possible that different people with different agendas could disagree? Kant allows for no exceptions to a duty, but that is unreasonable. Sometimes we are in situations where we need exceptions to a rule. Because Kant puts the idea of the Golden Rule into a rational formula that can indeed offer solutions to all moral problems. Because Kant shows an enormous amount of respect and faith in the human ability to reason, liberating humans from authorities who claim they know better. Because it leads to the next section in Kant’s “Grounding”: respect for all thinking beings.