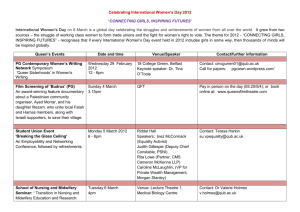

Poster - Queen's University Belfast

advertisement

The role of Networks within Public Health: Translating Evidence into Practice. H. McAneney1*, J.F. McCann2, 3, L. Prior3, 4, K. Balanda3, 5, J. Wilde3, 5 and F. Kee1, 3 1 School of Medicine, Dentistry and Biomedical Sciences, Queen's University Belfast 2 School of Mathematics and Physics, Queen's University Belfast 3 Centre of Excellence for Public Health (Northern Ireland) 4 School of Sociology, Social Policy and Social Work, Queen's University Belfast 5 The Institute of Public Health in Ireland Abstract Over the last five years within the UK, the Research Councils, the Department of Health and major charities have begun to address the need to build capacity in public health research and ensure better mechanisms for translating evidence into practice. Following reports such as Public Health Sciences: Challenges and Opportunities by the Wellcome Trust, major new ventures appear to have forged a common purpose to support “better research for better health” [1], for example the creation of Public Health Research Centres of Excellence [2]. This study has capitalized on the occasion of the launch of one such Centre to describe the social networks of its stakeholders and investigate the nature and extent of the relationships between them. Network measures Background: The NI Health Care System The NI health care system has gone under major reforms in the last few years. In November 2005, the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland announced a radical restructure of public administration structures within the province. The number of public bodies have been reduced significantly to make the public sector more streamlined and economically efficient. The impact on health and social care has been significant [3]. The details given below were correct at the time of the launch of the CoE in 2008, prior to the further reforms initiated on 1st April 2009. Centrality is a structural attribute of nodes in a network and is a measure of the contribution of network position to the importance, influence or prominence of an actor in a network. Centralisation is a network level measure which gives information regarding the overall network structure. Table 6: Top 6 nodes by degree, eigenvector and betweenness centrality measures [4,6] of Figure 3. See Table 2 for meaning of abbreviations. Regardless of measure, the same few organisations are central. Note the elevated position of the RDO in eigenvector and betweenness centrality. Centralisation measure In-Degree Out-Degree Eigenvector Betweenness BHSCT DHSSPS EHSSB HSCT IPH NICR QUB QUB_CCPS QUB_NM RDO UU 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Percentage 5 16 51 4 Eigenvector BHSCT DHSSPS QUB_CCPS UU EHSSB RDO Betweenness DHSSPS BHSCT QUB_NM UU IPH RDO Table 7: Centralisation measures of the network [4,6]. Note that the eigenvector centralisation, a weighted degree measure, indicates a cluster of a few dominate organisations, central in the network structure. Other values indicate a robust network. Chart 1: Organizational structure of the health service [3]. A trans-sectoral network is calculated by grouping the individual actors according to some pre-described attribute and then aggregating the number of ties directed towards each group[7,8]. In mathematical terms, the adjacency matrix is rearranged to form a specified number of groups, wherein each group contains nodes with the same attribute. The 193 organisations depicted in Figure 3 were organised according to their work sector, as were listed in Table 3. Belfast Health & Social Care Trust Department of Health, Social Services & Public Safety Eastern Health & Social Services Board Health & Social Care Trusts Institute of Public Health in Ireland Northern Ireland Cancer Registry Queen’s University Belfast Queen’s University Belfast, Centre of Clinical & Population Sciences Queen’s University Belfast, School of Nursing & Midwifery Research & Development Office University of Ulster Table 2: Abbreviations of organisational names In-Degree DHSSPS BHSCT IPH HSCT QUB UU Trans-sectoral Network Figure 1: The four Health and Social Services Boards [3]. Table 1: Population sizes of the four health and social services boards, 2002 [3]. Out-Degree QUB_CCPS EHSSB NICR DHSSPS QUB_NM BHSCT Figure 4: Trans-sectoral network were nodes have been partitioned into attribute based groups. The shape of the node is representative of the type of organisation (see caption to Figure 3). Node size corresponds to the number of organisations grouped together within each sector. Numbers close to each node indicate the number of nominations from one sector type toward another. Note that the network is unidirectional between academics and the third sector. 3.5 Figure 2: The five Health and Social Care Trusts within NI. Source http://fgcforumni.org/index.php 3 CoE for Public Health (NI) Network Initial work carried out included the creation, coding and analysis of a questionnaire on those who attended the launch of the UKCRC funded Centre of Excellence for Public Health (NI) [2]. This was to discern the potential placement of the CoE and the necessary role it could play within the local health sector. This involved obtaining the necessary information through questionnaires, of which 98 were returned. From the information given, a representation of the public health care sector within Northern Ireland was created and analysed. This involved the use of UCINET, Netdraw and SPSS software packages. Figure 5: A bubble chart of values attributed to impact and strength of collaboration. Both measures were rated from high (1) to low (3). A bubble chart is a two-dimensional scatter plot where a third variable is represented by the size of the points, in this case the frequency of choice. The coefficient of correlation between impact and strength is r = 0.5869. Therefore both are duly considered in Table 8. Strength 2.5 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 0 0.5 Table 8: Root mean sum of squares (RMSS), 1 1.5 2 2.5 3 3.5 Impact of impact (j=1) and strength (j=2) that participants regarded their contact with organisations. Scale of 1(strong) - 3 (weak), as partitioned/grouped into sectors. Entry (a:b) from row a and column b, gives the RMSS from block a to block b. This allows for a quantifiable measure of collaboration over the trans-sectoral network as directed from one sector to another. Those tran-sectoral connections with values missing may not be due to a lack of interaction, but rather a lack of data being collected at the CoE launch. For example, no for-profit organisation responded to the questionnaire and hence there were no nominations from this to other sectors. Note that the RMSS values are not necessarily equally reciprocated. Conclusions Table 3: Profile of participants of the questionnaire. 59 respondents were from the academic sector reflecting the composition of the CoE centred in the University, and will be reflected in the network structures. Figure 3: Network of 193 organisations and research clusters as named by attendees at launch. The shape of a node is representative of the type of organisation: = Statutory Public Health Delivery (53); = Policy-making, standard setting and professionals (37); = Third Sector (27); = Academic (60); = Commissioners of research (11); = For-Profit (4); and + = Primary Care (1). The colour of the nodes is then an indication as to whether that organisation was present at the symposium (blue if present, grey if not) and whether it has representation within the CoE (red). Lastly, the colour of the ties (edges) is an indicator of whether the relation is reciprocated or not. The red dashed ties denote reciprocated nominations (e.g. A B) whilst black solid ties are one-way nominations, where an organisation has named another but not vice versa (e.g. AB and A B). Table 4: How academic and non-academic participants personal goals relate to those of the UKCRC Northern Ireland Centre of Excellence in Public Health Research, with a chisquare test performed to see if these were the same. Note that non-academics’ goals are more strongly aligned with ‘Knowledge brokerage’ when compared to those of the academics (p-value = 0.002). Table 5: Academics were more inclined to believe that the CoE could increase the capacity for research than non-academics (p-value = 0.050), whereas non-academics were more confident than academics that the CoE could help deliver more Public Health interventions (p-value = 0.007). Using results obtained from 98 respondents from 44 organizations and research clusters we have been able to assess the expectations, goals, and network connections of the respondents. Analysis of data on participant expectations and personal goals suggest that the academic members of the network were more likely to expect the work of the Centre to produce new knowledge as compared to non-academics, but less likely to expect the Centre to generate health interventions and influence health policy. Academics were also less strongly oriented than non-academics to knowledge transfer as a personal goal, though more confident that research findings would be diffused beyond the immediate network. A social network analysis of our data suggests that a central core of around 5 nodes is crucial to overall configuration of the regional public health network in Northern Ireland, and that whilst the overall network structure is fairly robust, the connections, between some component parts of the network - such as academics and the third sector - are unidirectional. References: 1. Best Research for Best Health. A new national health research strategy. Department of Health, 2006. 2. www.qub.ac.uk/coe 3. Jordan, A., McCall, J., Moore, W., Reid, H., Stewart, D., 2006. Health Systems in Transition: Northern Ireland. Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for Europe on behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. 4. Borgatti, S. P., Everett, M. G., Freeman, L. C., 2002. Ucinet 6 for Windows: Software for Social Network Analysis. Harvard: Analytic Technologies. 5. SPSS for Windows, Rel 15.0.1.1. Chicago: SPSS Inc. 2008. 6. Carrington, P. J., Scott, J., Wasserman, S. (Eds.), February 2005. Models and Methods in Social Network Analysis (Structural Analysis in the Social Sciences). Cambridge University Press. 7. Norman, C. D., Huerta, T., 2006. Knowledge transfer & exchange through social networks: building foundations for a community of practise within tobacco control. Implementation Science 1, 20. 8. Lewis, J. M., Baeza, J. I., Alexander, D., 2008. Partnerships in primary care in Australia: Network structure, dynamics and sustainability. Social Science & Medicine 67, 280–291. * Email: h.mcaneney@qub.ac.uk for further information