Gastroparesis: Pathophysiology and

management

Preceptor: Dr. Govind Makharia

Speaker: Dr. Moka Praneeth

Gastroparesis-Overview

Definition

Epidemiology

Pathophysiology

Clinical Manifestations

Diagnosis

Treatment

Definition

The diagnosis of gastroparesis is based on the combination

of

symptoms of gastroparesis,

absence of gastric outlet obstruction or ulceration

(documneted on UGIE or Barium swallow),

and documentation of delay in gastric emptying.

Michael Camilleri et al. Clinical Guideline: Management of Gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013

Gastroparesis in Olmsted County, 1996–2006

Incidence

The age-adjusted prevalence of definite gastroparesis per 100,000

person was 9.6 (95% CI, 1.8–17.4) for men and 37.8 (95% CI, 23.2–52.4) for

women.

Incidence & prevalence of gastroparesis in India: ?

Jung HK et al. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010

Gastroparesis: Etiology

Kendall and McCallum. Gastroenterology 1993.

Soykan et al. Dig Dis Sci 1998.

Electrophysiologic basis of gastric peristaltic waves

Gastric neuromuscular work after ingestion of a solid meal

Normal gastric emptying

The proximal stomach serves as the reservoir of food, and the

distal stomach as the grinder

Solids are initially retained in the stomach and undergo churning

while antral contractions propel particles toward the closed

pylorus.

Food particles are emptied once they have been broken down to

approximately 2 mm in diameter

Gastric neuromuscular disorders

Diabetic gastroparesis-pathophysiology

NOS – impaired expression

Gastric myenteric plexus of spontaneously diabetic

biobreeding /Worcester (BB/W) rats was studied

NANC relaxation in gastric muscle preparations in response

to transmural stimulation obtained from diabetic BB/W rats

was significantly impaired

Takahashi T et al. Gastroenterology. 1997 Nov

NOS – impaired expression

The number of NOS-immunoreactive cells in the gastric

myenteric plexus and the NOS activity were significantly reduced

in diabetic BB/W rats.

Northern blot analysis showed that the density of NOS

messenger RNA bands at 9.5 kilobases was significantly reduced

in the gastric tissues of diabetic BB/W rats.

Takahashi T et al. Gastroenterology. 1997 Nov

Watkins CC et al. J Clin Invest. 2000

Patterns of Gastric Emptying in Healthy People and in

Patients with Diabetic Gastroparesis

Idiopathic gastroparesis/IG – intact

vagal function

13 normal subjects, 9 patients of DG, 10 patients of IG, 5

patients of postsurgical gastroparesis

There were significantly decreased fasting levels of

pancreatic polypeptide and ghrelin in the diabetic

(79±26pg/ml) and postsurgical gastroparesis groups (51±11

pg/ml) compared to the normal subjects (315±76 pg/ml)

and the idiopathic gastroparesis group (161±53 pg/ml).

Gaddipati KV et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2006

IG – intact vagal function

Sham feeding was characterized by an increase in

pancreatic polypeptide levels in normal controls and

patients with idiopathic gastroparesis, with no change in

diabetic and postsurgical gastroparesis.

Meal ingestion resulted in an increase in pancreatic

polypeptide concentration in the normal subjects groups

and idiopathic gastroparesis group.

Gaddipati KV et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2006

IG & DG-cellular changes

Full-thickness gastric body biopsy specimens were

obtained from 40 patients with gastroparesis (20 diabetic)

and matched controls.

Sections were stained for H&E and trichrome and

immunolabeled with antibodies against PGP 9.5, nNOS,

VIP, substance P, and tyrosine hydroxylase to quantify

nerves, S100β for glia, Kit for ICCs, CD45 and CD68 for

immune cells, and smoothelin for smooth muscle cells.

Grover M et al. Gastroenterology. 2011 May

IG vs DG-cellular changes

Histologic abnormalities were found in 83% of patients.

The most common defects were loss of ICC with remaining ICC

showing injury, an abnormal immune infiltrate containing

macrophages, and decreased nerve fibers.

On light microscopy, no significant differences were found

between DG and IG with the exception of nNOS expression,

which was decreased in more patients with IG (40%) compared

with DG patients (20%) by visual grading.

Grover M et al. Gastroenterology. 2011 May

IG vs DG- Ultrastructural differences

Tissue was collected from anterior aspect of stomach,

midway between GC and LC where the gastroepiploic

vessels meet, at ~ 9 cm proximal to pylorus, from 20 DG, 20

IG and 20 patients undergoing gastric bypass for obesity

4 tissue strips for each patient 1 mm × 10 mm long and

containing the muscularis propria plus a small portion of

the tunica submucosa, were immediately cut after the full

thickness biopsy was obtained and processed for electron

microscopy

The NIDDK GpCRC J Cell Mol Med. 2012 July

IG vs DG- Ultrastructural differences

ICC were affected in both diabetic and idiopathic gastroparesis.

19/20 DG patients had a thickened basal lamina around smooth

muscle cells and nerves.

In contrast, tissues from 18/20 patients with IG did not have the

thickened basal lamina around smooth muscle cells and nerves

but had more intense fibrosis than those from DG

Nerve damage was much more prominent in IG with both nerve

cell bodies and nerve fibers affected to a greater degree.

Unlike in DG, glial cells were also abnormal in IG

The NIDDK GpCRC J Cell Mol Med. 2012 July

Clinical Manifestations

Nausea

92%

Vomiting

84%

Bloating

75%

Early Satiety

60%

Abdominal pain

45-90%

Rule out rumination syndrome

Soykan et al. Dig Dis Sci. 1998 Nov; 43(11):2398-404.

Dyspepsia & gastric emptying

In a meta analysis of 17 studies involving 868 dyspeptic

patients and 397 controls, significant delay of solid gastric

emptying was present in 40% of patients of FD1

Severity of delay does not correlate with symptoms

Rapid gastric emptying, rather than delayed gastric

emptying, might provoke functional dyspepsia.2

1. Perri F et al. Am J Gastroenterol 1993.

2. Kusano M et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011 Apr

Gastroparesis: a proposed

classification

Grade 1: Mild gastroparesis

Symptoms relatively easily controlled

Able to maintain weight and nutrition on a regular diet

or minor dietary modifications

Grade 2: Compensated gastroparesis

Moderate symptoms with partial control with

pharmacological agents

Able to maintain nutrition with dietary and lifestyle

adjustments

Rare hospital admissions

Grade 3: Gastroparesis with gastric failure

Refractory symptoms despite medical therapy

Inability to maintain nutrition via oral route

Frequent emergency room visits or hospitalizations

Abell et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil (2006) 18, 263–283

Diabetic Gastroparesis (DG)

Prevalence of delayed emptying in longstanding Type-1 and

2 Diabetics: 27-58% and 30% respectively

Diabetic gastroparesis typically develops after DM has

been established for ≥10 years, and patients with type 1

diabetes might have triopathy

DG-natural history

20 patients (6 men and 14 women) of diabetes mellitus (16

with type-1 DM, 4 with Type-2 DM)

No differences in mean gastric emptying of the solid

component (retention at 100 minutes at baseline: 56% +/19% vs. follow-up: 51% +/- 21%, P = 0.23) or the liquid

component (time for 50% to empty at baseline: 33 +/- 11

minutes vs. follow-up: 31 +/- 12 minutes, P = 0.71) during

follow-up

Jones KL et al. Am J Med 2002

DG-natural history

Mean blood glucose (17.0 +/- 5.6 mmol/L vs. 13.8 +/- 4.9

mmol/L, P = 0.007) and HbA(1c) (8.4% +/- 2.3% vs. 7.6% +/1.3%, P = 0.03) levels were lower at follow-up.

There was no difference in symptom score (baseline: 3.9

+/- 2.7 vs. follow-up: 4.2 +/- 4.0, P = 0.78).

There was evidence of autonomic neuropathy in 7 patients

(35%) at baseline and 16 (80%) at follow-up.

Jones KL et al. Am J Med 2002

DG-natural history

Between 1984-89, 86 patients of DM underwent

assessment

Solid gastric emptying percentage of retention at 100 min)

was delayed in 48 (56%) patients and liquid emptying (50%

emptying time) was delayed in 24 (28%) patients.

At follow-up in 1998, 62 patients were known to be alive, 21

had died, and 3 were lost to follow-up.

1. Kong MF et al. Diabetes Care 1999

DG-natural history

In the group who had died, duration of diabetes (P = 0.048), score

for autonomic neuropathy (P = 0.046), and esophageal transit (P

= 0.032) were greater than in those patients who were alive, but

there were no differences in gastric emptying between the two

groups.

Of the 83 patients who could be followed up, 32 of the 45 patients

(71%) with delayed solid emptying and 18 of the 24 patients (75%)

with delay in liquid emptying were alive

Gastroparesis was not associated with a poor prognosis

Kong MF et al. Diabetes Care 1999

IG vs DG - Differences

Out of 416 patients, 254 patients of IG, 137 with DG and 25 with

other causes

More likely to be female (89% vs 71%-T1 vs 76%-T2), Caucasians (90%

vs 77% vs 76%)

Mean Age at enrollment: T2DM (53 ± 11) > IG (41 ± 14) > T1 DM (39

± 11 years)

Obesity in: T2 DM (71%) vs 28% (T1DM) vs IG (26%)

The NIDDK GpCRC. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011

IG vs DG - Differences

Nausea and vomitings are the most common symptoms

prompting evaluation for DG

Abdominal pain was more often a symptom prompting

evaluation for IG (76% IG, 60% T1DM, 70% T2DM; p=0.01).

The NIDDK GpCRC. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011

IG vs DG - Differences

20% having chronic but stable symptoms, 33% having

chronic but worsening symptoms, 33% having chronic

symptoms with periodic exacerbation, and 10% having a

cyclic pattern.

Patients with T1DM were more likely to have grade 3

gastroparesis severity (29% IG, 49% T1DM, 39% T2DM) and

had greater frequency of hospitalisations due to

dehydration

The NIDDK GpCRC. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011

IG vs DG - Differences

The symptoms with highest severity at enrollment were stomach

fullness and postprandial fullness for IG, nausea for T1DM, and

stomach fullness for T2DM.

DG had more severe retching and T1DM had more severe

vomiting than IG

Severity of postprandial fullness and upper abdominal pain in: IG >

DG

The NIDDK GpCRC. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011

IG vs DG - Differences

Gastric retention in: T1 DM (47 ± 27% at 4 hours) > T2 DM (33 ± 24) > IG

(28 ± 19)

IG had an increase in endometriosis and migraine headaches, whereas

T2DM had an increase in coronary artery disease.

An acute onset of symptoms was reported in approximately half of the

patients in each of the IG, T1DM, and T2DM.

An initial prodrome was present at the start of symptoms in a minority,

approximately 15% of cases, without significant differences among the

three groups.

The NIDDK GpCRC. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011

Evaluation

Clinical Evaluation

Evaluate Volume Status

Abdominal distention, Succussion splash

Clues to other etiologies

Malar rash, sclerodactyly

Cachexia, lymphadenopathy

Lab

Electrolytes

Protein/albumin

Glucose

Thyroid/parathyroid

If suspected, autoantibodies for scleroderma, SLE,

polymyositis

Gastric emptying scintigraphy

Patient Preparation

NPO at least 3 hours prior to the

procedure

No smoking for 3 hours prior to the

procedure

Ensure that diabetics receive orange

juice 4-12 hrs before examination

Briefly explain to the patient:

The oral administration of the

radiotracer

Positioning and immobilization during

the imaging

Procedure

Time 1.5 hrs liquid, up to 3-4 hrs solid

Baseline solid Study:

Prepare one or two eggs/chicken liver/idli (in AIIMS) and mixed in

radiotracer

Stir and scramble

Or prepare choice of gastronomic vehicle with radiotracer

Administer to patient PO with 30-120 ml of water. Encourage

patient to eat quickly

Procedure (cont)

Patient Supine

Place patient in supine position.

Acquisition should be started as quickly

as possible after ingestion of food

Position camera anterior or LAO

Instruct patient to remain motionless

during imaging

Obtain Patient images every 5 minutes

up to 30 minutes, then every 15

minutes thereafter, allowing the

patient to ambulate between images

Or preset dynamic images for 60-90

minutes. Patient remain motionless

under camera

Supine is good for checking esophageal

reflux

Procedure (cont)

Patient standing

Position patient standing or sitting, one image facing

camera. Optional :one image with back to camera

Obtain immediate images, then every 10 minutes

Standing, sitting, then standing uses normal movement

and gravity to aid realism in study

Procedure Liquid Study

Baseline Liquid Study

Add 500 uci of 99mTc-DPA TO 120 ml,

of water or orange juice

Administer to patient PO, encourage

patient to drink quickly.

Images same as solid study, although

only imaged for 1.5 hours

Normal Results

Liquid (e.g., radiolabeled water or orange juice ) t1/2 (50%) at 10-15

minutes ) or 80% in 1 hour

Solid (Type and size of meals and population varies): t1/2 (50%) movement

out the stomach within a lower limit of 32 minutes to an upper limit of

120 min with and adult mean of 90 min.

Delayed GE (gastric retention) was determined to be >90% at 1 h, >60% at

2 h and>10% gastric retention at 4 h.

Terminate study before 60 min if gastric emptying becomes > 95%

Wireless motility capsule

Farmer A D et al. United European Gastroenterology

Journal 2013;2050640613510161

Farmer A D et al. United European Gastroenterology

Journal 2013;2050640613510161

Comparison of the various techniques, currently utilized, indicating their relative

advantageous and disadvantageous features.

Farmer A D et al. United European Gastroenterology

Journal 2013;2050640613510161

Clinical impact

The association of delayed emptying with specific symptoms is

relatively weak

Gastric emptying tests do not yield a high diagnostic specificity

With few exceptions, most studies have failed to demonstrate a

correlation between the severity of delayed emptying and

response to prokinetics

An initial treatment approach should be required before

performing gastric emptying test

In refractory patients or in those with symptoms that impair

nutritional status or the ability to function normally, assessment of

gastric emptying may play a pivotal role

Tack J et al. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2009

GERD-Gastric emptying study

Gastroparesis can be associated with and may aggravate

GERD.

Evaluation for the presence of gastroparesis should be

considered in patients with GERD that is refractory to acidsuppressive treatment.

Michael Camilleri et al. Clinical Guideline: Management of Gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013

Treatment algorithm

Dietary/Non-medical

Poor evidence Multiple small meals

Liquid instead of solid meals

Low fat, Reduce indigestible fiber

Discontinue medications that slow emptying if possible

Nutrition

If oral intake is insuffi cient, then enteral alimentation by

jejunostomy tube feeding should be pursued (after a

trial of nasoenteric tube feeding).

Indications for enteral nutrition include :

unintentional loss of 10 % or more of the usual body

weight during a period of 3 – 6 months

repeated hospitalizations for refractory symptoms.

Michael Camilleri et al. Clinical Guideline: Management of Gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013

Antiemetics

No evidence from controlled trials

Phenothiazines

Prochlorperazine (Stemetil)

Promethazine (Phenergan)

Serotonin 5-HT3 antagonists

Ondansetron (Zofran)

Muscarinic antagonisits

Butylscopolamine (Buscopan)

Prokinetics-algorithm

Metoclopramide (Maxalon)

Only FDA approved drug for gastroparesis

Erythromycin

Domperidone (Motilium/Vomidon)

Not FDA approved in US

Cisapride (Prepulsid)

Removed from market 2000

Cardiac toxicity

Pasricha et al. J Neurogastroenterol Motil, Vol.19

Endoscopic Therapy

Venting PEG

Botox injection – Pylorus

Pyloric Balloon Dilation (No published evidence)

Temporary placement of stimulation leads in stomach

to predict response to more permanent stimulator

Intrapyloric injection of Botox

23 patients (5 males, 19 idiopathic) underwent 2 UGIEs with 4

week interval

Injection of saline (in 11 as first injection) or botox 4×25 U (in 12

patients) in a cross-over RCT

Before the start of the study and 4 weeks after each treatment,

they underwent a solid and liquid gastric emptying breath test

with measurement of meal-related symptom scores, and filled out

the GCSI

Arts J et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007

Intrapyloric injection of Botox

Significant improvement in emptying and GCSI was seen

after initial injection of saline or botox.

No further improvement occurred after the second

injection

No significant difference in improvements of solid t(1/2)

and liquid t(1/2), meal-related symptom scores or GCSI

Arts J et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007

Surgical

Gastrostomy for venting and jejunostomy for

feeding

Completion gastrectomy in markedly symptomatic

PSG

Pyloroplasty (± jejunal feeding tube placement)

Subtotal gastrectomy + Roux-Y reconstruction for

gastric atony due to PSG)

Gastric Electrical Stimulation

Gastric Electric Stimulation

Gastric Neurostimulation (Enterra)

12 bpm

High Frequency (~ 4 x Slow Wave Freq)

Frequency

Low Energy with short pulse

Gastric Pacing:

3 bpm

Energy

Low Frequency (~ Slow Wave Freq)

High Energy with long pulse

Mechanisms of action of gastric

electrical stimulation

Unknown

Gastric emptying not consistently improved

Gastric dysrhythmias not normalised

Increased gastric accommodation

Increased vagal afferent activity

Increased thalamic activity

McCallum RW et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil

Enterra therapy: Humanitarian device

exemption

Enterra therapy was granted approval as a Humanitarian

Use Device (HUD) to be used in patients with refractory

diabetic or idiopathic gastroparesis, restricted to

institutions where Institutional review board approval has

been obtained

FDA 2000

Enterra therapy CE mark Indication

Enterra therapy is indicated for the treatment of patients

with chronic intractable (drug refractory) nausea and

vomitings secondary to gastroparesis

From: Gastric Electrical Stimulation: An Alternative Surgical Therapy for Patients With Gastroparesis

Arch Surg. 2005;140(9):841-848. doi:10.1001/archsurg.140.9.841

Figure Legend:

Diagrammatic representation of the laparoscopic placement technique showing trocar placement, lead placement in the stomach

wall, and position of the subcutaneous pocket for the neurostimulator.

Date of download: 1/30/2014

Copyright © 2014 American Medical

Association. All rights reserved.

Figure

4 Vomiting frequency

in patients

diabetic gastroparesis

after after implantation of a

Vomiting

frequency

in patients

withwith

diabetic

gastroparesis

implantation of a gastric electrical stimulator device

gastric electrical stimulator device

Permission obtained from Elsevier ©

McCallum, R. W. et al. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11, 947–954 (2010)

Hasler, W. L. (2011) Gastroparesis: pathogenesis, diagnosis and management

Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2011.116

Hasler, W. L. (2011) Gastroparesis: pathogenesis, diagnosis and management

Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2011.116

GES for the Treatment of Gastroparesis: A Meta-Analysis

Total Symptom Severity Score

13 papers

Requirement for Enteral or

Parenteral Nutritional Support

Vomiting Symptom Severity Score

Change in Weight (kg)

Nausea Symptom Severity Score

O’Grady G, et al. World J Surg 2009; 33:1693-1701

GES for the Treatment of Gastroparesis: A Meta-Analysis

Complications

8.3 %

(22/265 patients, 10/13 studies)

Infection

8

Skin erosion

6

Pain at site

4

Gastric perforation

2

Device migration

1

Volvulus

1

O’Grady G, et al. World J Surg 2009; 33:1693-1701

GES for the Treatment of Gastroparesis: A Meta-Analysis

A meta-analysis of 10 studies (n = 601) using high-frequency GES

to treat patients with gastroparesis from January 1995 to January

2011

GES significantly improved both TSS (P < 0.00001) and gastric

retention at 2 h (P = 0.003) and 4 h (P < 0.0001) in patients with

diabetic gastroparesis (DG), while gastric retention at 2 h (P =

0.18) in idiopathic gastroparesis (IG) patients, and gastric

retention at 4 h (P = 0.23) in postsurgical gastroparesis (PSG)

patients, did not reach significance.

Chu H et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012

Glucose Control in Diabetic gastroparesis Patients

HbA1c Reduction

at 6 and 12 months vs. Baseline

10.0%

Baseline 9.8%

Baseline 9.4%

9.0%

At 6 mths

At 6 mths

At 12 mths

8.5%

Baseline 8.6%

•Forster et al: Further experience with gastric stimulation to

treat drug refractory gastroparesis. Am J Surgery 2003;

186(6): 690-695

At 12 mths

8.4%

8.0%

•Lin et al: Treatment of Diabetic Gastroparesis by HighFrequency Gastric Electrical Stimulation. Diabetes Care 2004;

27(5), 1071-1076.

7.0%

At 12 mths

6.5%

At 6 mths

6.0%

Forster 2003

Lin 2004

Van der Voort

2005

•Van Der Voort et al: Gastric Electrical Stimulation Results in

Improved Metabolic Control in Diabetic Patients Suffering

From Gastroparesis. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2005;

113:38-42

Nutritional Support

Nutritional Support Reduction

Patient Number

25

20

9

15

TPN

10

J-tubes

5

13

5*

* p < 0.05

0

Baseline

12 mths

48

28

n

Lin et al: Treatment of Diabetic Gastroparesis by High-Frequency Gastric

Electrical Stimulation. Diabetes Care 2004; 27(5), 1071-1076

Conclusion

More studies on gastroparesis are warranted in India

WMC is as good and has advantages compared to gastric

emptying scintigraphy, the gold standard

GES is a good choice for refractory gastroparesis

Treatment options are likely to improve after the

pathophysiology of gastroparesis is better understood.

Thank you

WAVESS*: Study Design

Multicenter double blind crossover

ON

R

Baseline

a

n

d

Implant o

m

1/2

1/2

OFF

Phase I

0

N=

33

Phase II

1

2

33

33

6

12

Months

27

24

Patients

17 diabetic

16 idiopathic

* Worldwide Anti-Vomiting Electrical Stimulation Study

Gastric Electrical Stimulation

Enterra System (Medtronic)

The History of Gastric Stimulation

1972: Kelly and Laforce at Mayo Clinic induced antegrade and retrograde

conduction of slow waves in canines with gastric stimulation.

1988: McCallum et al at University of Virginia showed increased gastric

emptying in canines with vagotomy

1997: Familoni et al reported improved peristalsis in canines with GES

1998: The WAVESS study group demonstrated the feasibility of GES, leading

to Enterra therapy.

The History of Gastric Stimulation

1963 – Bilgutay et al.: Gastric stimulation was practiced for

the treatment of postoperative ileus.

Surgery

Laparoscopy - 3 Ports

Left upper quadrant port becomes

stimulator pocket

Length of stay: 2-3 days

Evaluate neurostimulator parameters

before discharge

Lead Location

Greater curvature

Leads placed

10cm from pylorus

Utilize measuring

tape or 10cm suture

length

Leads 1cm apart

Lead Placement

Proximal anchoring

point utilizing

winged/trumpet anchor

One centimeter

electrode length in

stomach wall

Lead Fixation

Disc sutured to

stomach wall

1-2 sutures

Lead suture wire

clipped to disc

1-2 clips

Switch on and interrogation

Device is initiated

remotely

A system check is

performed and

impedance is checked

Power setting is

programmed and

rechecked on

discharge

Comparison of methods used to assess gastric

emptying

Parkman et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010 Feb

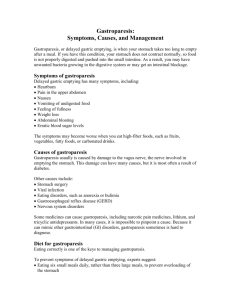

Gastroparesis: Pathophysiology

Excessive

relaxation

Poor

antro-pyloro-duodenal

synchronisation

Abnormal

duodenal

motility

Antral

hypomotility