Cereal Grains

advertisement

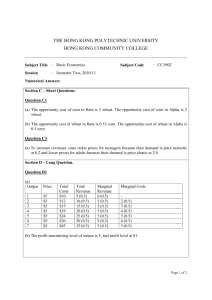

Cereal Grains David S. Seigler Department of Plant Biology University of Illinois Urbana, Illinois 61801 USA seigler@life.uiuc.edu http://www.life.uiuc.edu/seigler OUTLINE Importance: • to hunter-gatherers • to agricultural societies Historical role: • how eaten Botanical information: • distribution • systematics: Poaceae (Gramineae); nearly 8,000 species, but only about 35 species cultivated. • anatomy-morphology Properties • physical • nutritional • lysine Human selection • replanting • harvesting methods Some characters selected: • tillers • shortness • non-shattering • separation of fruits from inflorescence • disturbed habitat • synchronous ripening • more fruits • larger fruits • lack of sensitivity to day length • glutinous properties (wheat) Most important cereal grains today • wheat - historical, today's perspective, steps in origin, where and why cultivated, disease problems- Near Eastern origin • rice - Asian and African species • corn - Mexican origin • sorghum - African origin • most ancient cereal grain: barley Reading • CHAPTER 5 IN TEXT Introduction • More than 70% of the world's farmlands devoted to the cultivation of cereal grains. • More than one half of the total calories consumed by humans. • Domestic animals fed primarily by cereal grains. • Society as we know it could not exist without cereal grains. • Oldest of cultivated crops. Grasses used long before that. Courtesy Dr. Ted Hymowitz • Wheat and barley sustained the Near Eastern cultures, rice the Far East, corn the pre-Columbian New World cultures, and sorghum a number of African ones. Grains in the grass family (Poaceae or Gramineae). • One seeded fruit (a caryopsis) has a seed coat fused with the ovary wall. • There are nearly 8000 species of grasses. • The seeds of most grasses are edible. Major grains and producers • The world's major grains are listed on pg. 110. • The major producing countries are listed on pg. 110. Artificial selection of grasses • Populations are variable and stable only for a given situation. • A change in selection pressure will cause a change in the genetics of the plant involved. • Domestication is an evolutionary process under the influence of humans. Domestication • As long as gatherers only gather, they exert little selective pressure. The plants are reseeded during the harvest by "shattering". • This was true for grass harvesting by most of the North American Indians. They bent the grass over and hit the heads with a stick to loosen the grains. This would also favor ripening over time and seed dormancy. Harvesting wild rice by traditional methods Replanting • The key factor in domestication was when humans began to replant the seeds. • Non-shattering, determinate growth, larger and more seeds, increased inflorescence size, fewer sterile flowers, tolerance for disturbed habitat, and lack of seed dormancy favored. • Weeds adapted to disturbed sites. • Related weeds may hybridize with the crop plant. • Eventually, the crop only survives because of humans and vice versa. • The major cereal grains are rice, wheat, and corn. Grasses • Grass plants occur in all parts of the world. • Monocotyledonous plants. • Many grasses branch at the base and produce more or less equal sized stems called tillers. • The leaf has a blade and a sheath that surrounds the stem or culm. • The regions where the leaves originate are called nodes. See the diagram on pg. 112. • Horizontal stems that grow along the ground are called stolons. • Grass floral structures complex. • Most grass flowers are perfect. • Grass flowers borne in compound inflorescences called spikelets. • A floret is an individual grass flower. (see pg. 112). Grass flowers • Superior ovary topped by two feathery stigmas. • Three stamens and three scale-like remnants of petals. • Each floret is enclosed in two bracts. The inner is called the palea and the outer the lemma. • Nerves of lemma extend and are called an awn. • There are two more sterile bracts called glumes. • Fruit is a caryopsis. • Food energy is stored as endosperm. • The storage product is mostly starch, but grains also have moderate amounts of protein and some fats. • Grains relatively low in water (10-13%). See pg. 114. • Many cultivated grasses are self-compatible annuals that invest a large portion of their energy as fruits. Directions of selection of grains One major change was grasses with tillers that mature synchronously. All plants and tillers mature fruits at the same time. The inflorescences have undergone even greater change than the vegetative portions. A single harvest that collects almost all the seeds produced. Shorter plants that don't lodge so readily. • “Non-shattering” fruits. Good for humans when they harvest grains, but not good for seed dispersal for wild plants. • These seeds became preferentially collected and replanted. • All major cereal grains now have nonshattering inflorescences. • Separation of fruits from inflorescence parts once stalks have been cut. • Grains separate below attachment of bracts or above them. • The bracts are called "chaff". • Removing the grains from the bracts is called "threshing". • The chaff is removed by winnowing. • Removal of fruit walls or "pearling”. Some important points 1. Cooking improves edibility. Most parched or popped originally. 2. They store easily, are nutritious and "concentrated". 3. They can be mechanically harvested. Barley (Hordeum vulgare) • Barley (Hordeum vulgare) is the earliest cereal to have been domesticated. Cultivated 10,000 years ago. • Wild forms are all two row. The oldest cultivated forms are also two row. • This type of barley has one fertile floret in the central spikelet of three at each node. • By 6000 B.C., six row forms had appeared. Each node has three spikelets and one floret in each matures. See pg. 116. Barley, Hordeum vulgare • In barley, each node bears 3 spikelets, a central one and two lateral ones. • Each spikelet bears a single floret. • In the 2 row types, 1 floret is fertile in the central spikelet and one is sterile in each of the two lateral spikelets. • In 6 row types, all florets are fertile, one in each of the three spikelets. • Barley arose in the Near Eastern center. • Also domesticated in China and Tibet and in Ethiopia. • Originally made into a paste and baked. • When soaked in water to make the grain more digestible, fermentation was discovered. • Baking and brewing are part of the same operation. • Barley was the major cereal until about 200 B.C. (2000 B.C. in the book). Supplanted by tetraploid wheat. • About half in U.S. used to feed livestock • Another fourth used to make beer and whiskey. • Worldwide, barley is now the number four cereal grain. Wheat • Wheat not quite as old as a cultivated crop as is barley. • Wild and early domesticates of wheat were diploid (2n = 14) (Triticum monococcum). • Early in domestication, a mutation arose that suppressed shattering. • Wheat with this mutation quickly became the major cultivated type. • Today called einkorn wheat. • By 8th century B.C., einkorn and another species hybridized and produced a tetraploid wheat. • The other species could have been T. searsii, T. urartu, or T. speltoides. • One tetraploid was called emmer wheat (Triticum turgidum) (see pg 117). • A mutation in one variety caused the glumes to collapse. Made separation of chaff easy. • Tetraploidy gave rise to durum wheats (pasta) (T. durum). • This change also combined proteins in the seeds to make gluten. Gluten is essential to make bread of the style we know. Celiac disease. • Later, a hexaploid wheat arose. This hexaploid called T. aestivum. • The other parent seems to have been T. tauschii. • Has a hard endosperm and best for bread making. • Hexaploid wheat is not known to occur in the wild. • Winter and spring wheat. • Most cultivars from wheat brought to the U.S. by Mennonites in late 1800's from Russia and the Ukraine. • Wheat has lots of disease problems. Puccinia graminis, or wheat rust. • Production of cultivars with resistance is very important, but it’s difficult to make hybrids. • Resistant lines tend to last about three years before disease catches up. • Wheat mostly grown in cool, dry climates. Moderate rainfall. • Major crop in 5 continents. Russia, Ukraine, midwest U.S., Canada, central Europe, Turkey, Argentina, N.E. China, N.E. Australia, N.W. India most productive regions. • The "green revolution". • Bran and wheat germ is removed. Winter wheat in Oklahoma Harvesting wheat Shocks of wheat in Austria Harvesting wheat in Colombia Rye (Secale cereale) • Rye appears to have developed as a cultivated crop from weeds in wheat and barley fields. • Fully domesticated about 3000 B.C. • Native to southwest Asia. • Rye can grow in colder areas than almost any other cereal grain. Grows well in northern Europe. • Rye bread almost always contains wheat as well. Rye doesn't have gluten. Rye, Secale cereale Oats, Avena sativa • Oats probably arose as a weed. • The last of the major cereals domesticated in the Near East, perhaps as late as 1000 B.C. • Also now a hexaploid oat, Avena sativa. No longer known in the wild. • Typically grown in cold areas to feed animals. Oats, Avena sativa • Disease resistance limits use in warmer parts of the world. • Used by Romans. They called the Germans "oat eating barbarians". • Oats are high in protein and fat. Often used to feed horses. Oats, Avena sativa Rice (Oryza sativa) • Rice feeds more people than any other crop. 1.7 X 109 people eat rice as their major food plant daily. • Most important in the Orient. • Although originally domesticated in Asia, the exact site of origin is uncertain. Previously thought in India, Burma, Thailand, or Viet Nam. New evidence suggests the Yangtze valley in China. • Other species of rice (e.g., Oryza glaberrima) were domesticated in Africa. • Rice in Thailand before 4500 B.C. and in China by 3000 B.C. New data suggests as early as 10,000 years ago. • Rice widespread in India by 2000 B.C. • Alexander the Great brought the grain back to Europe from India about 300 B.C. • By 15th century, rice was cultivated in both Spain and Portugal. • The Portuguese introduced rice into Brazil and West Africa. • In the 16th century, the English imported rice from Madagascar. • Rice an important crop in early South Carolina (1647). • Most rice in U.S. from Arkansas, California, Louisiana, and Texas. • Most rice (perhaps 90%) is grown and consumed in the Orient. Rice in Java Rice cultivation in the Orient I. Polunin. Plants and Flowers of Malaysia, Times Editions, Singapore 1988. Courtesy Dr. Dorothea Bedigian Rice, Oryza sativa Rice Threshing rice in Madagascar • ”Long grain" and "sticky" types. • Paddy and upland rice (Brazil the largest producer of upland rice). • Paddy rice is labor intensive. Mostly grown in the Orient. Almost all mechanized in the U.S. Planted by airplane. • Most rice polished today. Many of the nutrients lost. Causes vitamin B1 or thiamine deficiency. • In Asia and Africa, hybridization of rice with "weed" strains causes serious problems by reintroducing the shattering characteristic into the crop type. • Perennial rice species were harvested in S.E. Asia before annual rice. They do not yield so well. • Rice was not an important crop in much of Indochina, the Philippines, and Indonesia until about a century ago. This is partly linked to the production of new non-lodging varieties. • Asian rice was introduced into Africa where it has displaced native rice cultivars. Wild rice, Zizania aquatica A New World species, Zizania aquatica, has long been wild harvested. The inflorescences shatter. The grain was collected by beating the mature inflorescences into canoes. In the late 1950's, farmers started cultivating wild rice in Minnesota. Plant breeders developed a non-shattering variety recently. Sorghum ( Sorghum bicolor) • • • • • Sorghum native to Africa. Several domestication events involved. Between 2200 and 4000 B.C. Numerous cultivated types. Used to feed animals (stalks), for grain and for fiber (broomcorn). • A plant of hot climates and low rainfall. Sorghum ( Sorghum bicolor) • Very important in India and in many areas of Africa. • Used to make bread (but doesn't rise), "pop" sorghums, and beer. • Used in the Southeastern U.S. to make a type of molasses. Sorghum, Sorghum bicolor Johnson grass, Sorghum halepense Millets • Many grass cultivars that are locally important crops in localized areas of the world. • Millets especially important in areas of India. • Among them, Eleusine coracana and Pennisetum americanum are especially important. • See pg. 126. A millet, Eleusine coracana Courtesy Dr. J. M. J. de Wet Corn or Maize • Maize (Zea mays) is a New World crop. • The only major cereal grain domesticated in the New World. • Corn was the major food plant of all major New World civilizations, e.g., the Mayan, Incan, and Aztecan, although Amaranthus was also important in some regions. See diagram p. 130. • Many American Indians planted squash, corn and beans. This provided a relatively balanced diet. • Cultivation of corn in Mexico may go as much as 7,000 years. • Small cobs (1/2 inch long) have been found in the Tehuacán valley and in Tamaulipas. • By 3000 (5000?) B.C., essentially modern corn was being cultivated. • New evidence based on phytoliths suggests that essentially modern corn arose in Mexico as early as 10,000 years ago. • Corn was also cultivated in Peru by about 7000 years ago. • The greatest diversity for corn today is in Peru, but wild ancestors are from Mexico. • In 1492, corn was cultivated from Canada to Argentina. • How did corn arise? Corn is related to teosinte, Zea mexicana. Corn and teosinte cross readily and teosinte is found around corn fields in some parts of Mexico. • Teosinte is the major, if not the only, ancestor of corn. See diagrams pg. 130 and 132. Teosinte in Mexico Courtesy of Dr. J. M. J. de Wet Teosinte, Zea mexicana Courtesy of Dr. J. M. J. de Wet Teosinte ears and seeds Proposed origin of maize ear Yoking of corn kernels Steps in the formation of corn ears • Went from a fragile to a non-fragile ear. • From spikelets suppressed to both spikelets fertile. • Ear two ranked to four ranked. • Glumes hard to glumes soft. • Glumes cover seed to glumes short • Seed imbedded in rachis to seed exposed. • Seed small to seed large. Primitive corn ears Corn or maize, Zea mays Male and female corn structures Carolina Biological Supply Co. Evidence for early production of corn in Peru Phytolith images http://phytolith.missouri.edu/RTF/Figures/Figure1.jpg University of Missouri Phytolith Database • Columbus took corn back to Europe on his first voyage. • The Aztecs ate corn treated with lime. • In the southeastern U.S., Indians treated it with wood ashes. • These treatments partially hydrolyzed the starches etc. Nixtamal or hominy. • The Aztecs used nixtamal to make tortillas, tamales, and chocolate drinks. Posolero for making posole • • • • Corn is deficient in lysine and tryptophan. Most corn in the U.S. fed to animals. Corn starch used to make syrup. Corn is now one of the major sugar producing plants of the U.S. • Corn is now a major source of ethanol for fuel in the U.S. • Hybrid corn made by using inbred, highly homozygous lines. This is easy because corn is monoecious. • In 1935, only 1% hybrid corn used. • Mostly single cross now, but double cross method also important. Production of hybrid corn seed • Before corn could be grown in the northern U.S. and Canada, a loss of sensitivity to day length also had to occur. • Major types of corn: flint corn (N.E. U.S. Indians); dent corns (S.E. U.S., high yielding, soft starch); flour corns (soft starch, S.W. U.S. Indians, easy to grind by hand); sweet corn (high in sugar, eaten green) and popcorn (done to make corn more palatable). • Major producers. See table in book. Pseudocereals Some pseudocereals are important today; others have been extremely important in the past. Amaranthus was the second most important crop in Mexico in early 1500's. Because of its association with sacrifices and religion, the Spanish tried to put down its use. Cultivation of Amaranthus has survived until the present. • Many have advocated using amaranth as a cultivated crop. • Amaranth is nutritious and can be cultivated with most modern farm equipment with some modifications. • The major problems are lack of an established market and public acceptance. • Several species of Chenopodium also have been cultivated in both Mexico and in PeruBolivia. • In South America, these are called quinoa. Grain amaranth, Amaranthus sp. Amaranth cultivated in Bolivia. Courtesy Dr. Tim Johns Amaranth infructescence and seeds Amaranthus retroflexus, a weedy amaranth species of Illinois Pepitas, seeds of Cucurbita pepo Cucurbitaceae Field with quinoa, a Chenopodium sp., in Bolivia Courtesy Dr. Tim Johns Winnowing quinoa and quinoa seed Courtesy Dr. Tim Johns Buckwheat, Fagopyrum esculentum, Polygonaceae