Arctic Aff - Open Evidence Project

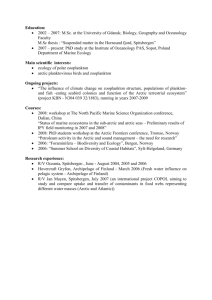

advertisement