CRG Compte rendu du séminaire Management de l'Innovation

CRG

Compte rendu du séminaire Management de l’Innovation

« How do firms identify and make use of external sources of knowledge?

A boundary-spanning perspective »

Par

Felipe Monteiro, INSEAD

Discutants

Nicolas Lesca,

Université Grenoble Alpes

Rémi Maniak, Telecom ParisTech

46

ème

séance du 12 février 2015

Compte-rendu rédigé par Julie Fabbri

Le 12 février 2015 s’est tenue la 46

ème

séance du séminaire Management de l’Innovation : théories et pratiques, de la Chaire MI-X, avec Felipe Monteiro (Insead) sur le thème « How do firms identify and make use of external sources of knowledge? A boundary-spanning perspective ». Les discutants étaient Rémi Maniak (Telecom ParisTech) et Nicolas Lesca

(Université Grenoble Alpes).

Abstract

An increasingly important capability of firms is related to the sourcing and exploitation of external knowledge. Establishing scouting units is a way through which firms source knowledge beyond their boundaries. However, we know little about how these units mediate the flow of ideas and technologies between their environment and the various relevant actors within the firm located all over the world. Based on a seven year longitudinal study of a

Silicon Valley-based scouting unit and its multinational parent firm in Europe, F. Monteiro focuses on the processes through which external sources of knowledge are identified and exploited. He shows that four boundary-spanning processes coexist. Beyond a simple onedirectional “channelling” process, he characterizes three higher value-added processes, labelled “translating”, “matchmaking” and “transforming”. He proposes an integrative view and defines a parsimonious set of conditions under which each of the four processes is likely to emerge. He also shows how the unit performs the more value-adding boundary spanning processes. Finally he highlights the dynamics and shifts over time in the balance between the types of processes from lower- to higher value added.

Biography

Felipe Monteiro is an Assistant Professor of Strategy at INSEAD. He obtained his PhD in

Strategic and International Management at the London Business School. Before joining

INSEAD, he was a standing faculty member at The Wharton School, University of

Pennsylvania. Prior to that, Professor Monteiro was a Fellow at the London School of

1

CRG

Economics and Political Science (LSE). He has also worked as a Senior Researcher at the

Harvard Business School’s Latin American Research. And prior to joining academia, Felipe was a Senior Analyst at Banco do Brasil acting as an advisor to foreign companies investing in Brazil.

His current research focuses on global open innovation and on knowledge processes within multinational corporations (MNCs), in particular, on how MNCs access external knowledge across organizational, technological and geographic boundaries. Felipe is also leading a research project on foreign direct investment strategies of MNCs headquartered in the BRIC

(Brazil, Russia, India and China) countries.

Presentation

Research on Knowledge Sourcing

To compete effectively in a fast-changing world, firms need to develop external knowledge sourcing, which is the ability to tap into new ideas and technologies beyond their boundaries.

F. Monteiro (F.M.) aims at understanding the very beginning of innovation processes, the

“fuzzy front-end”, which is usually overlooked.

FM studies the boundary spanning process through which firms identify and make use of external sources of knowledge. Boundary spanning units may take many forms (e.g. scout, corporate venture unit, business development, and external relations). They play a vital role in external knowledge sourcing, as a primary conduit through which ideas and technologies from the outside world get internalized by the MNCs. Their job deals with going outside and searching external knowledge – they don’t manufacture or sell anything.

Unlike other settings where the boundary spanner is “close to the action” (e.g. R&D units, investor relations), in MNCs many times boundary spanning takes place several thousand miles from headquarters. Also, quite often it requires crossing geographic, organizational and technological boundaries at the same time!

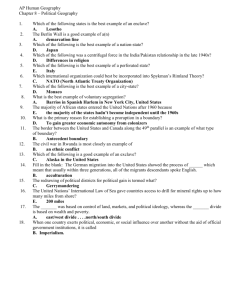

Thus, the research questions are:

What is the nature of the boundary-spanning process in MNCs and what different forms does it take?

Under what conditions do we see each of these forms?

How do boundary spanning processes evolve over time?

Empirical setting

FM and his coauthors conducted an in-depth study of one Silicon Valley-based scouting unit and its parent company in Europe, Europ Telco, one of the largest telecommunication services providers in the world, over a seven year period. They conducted 75 semi-structured interviews with all managers involved in the scouting unit both in Europe, US, and Asia; numerous corporate and business units managers at the parent company and several start-ups and venture capitalists Europ Telco dealt with.

They also undertook field observations and were given access to a proprietary internal database providing detailed information on technologies assessed by Europ Telco’s scouting unit managers in Palo Alto over a three year period.

3 types of Boundary Spanning processes

1. Translating process: scouts used their expertise to transfer tacit and context-specific knowledge across the boundary of the organization. It is the most complex boundary spanning

2

CRG process. When there is a lack of common ground between external and internal actors, we observe a translating process to establish a common language.

2. Matchmaking process: scouts sought to make a connection between specific external and internal actors. When there is a high level of uncertainty in the mediation opportunity, in terms of who to connect to whom, we observe a matchmaking process.

3. Transforming process: scouts used their expertise to help internal actors redefine their needs so they could access information to help them meet their objectives. When there is a lack of common ground and a high level of uncertainty we observe a transforming process.

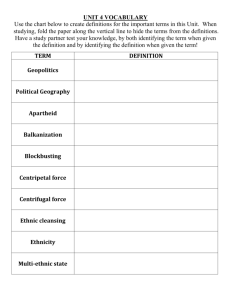

Importance of Social capital

Social capital is the set of resources an actor has built up over time as a function of its relationships. Or more formally, “ the sum of the actual and potential resources embedded within, available through, and derived from the network of relationships possessed

”

(Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998: 243).

Social capital is an enabler of boundary spanning processes. There are three dimensions of social capital that matter to enable the different processes:

Structural: being a place where a unit sits within the network

Cognitive: ability to provide shared representations, interpretations and systems of meaning

Relational: assets, such as trust, which are rooted in the relationship

Overview: contingencies and capabilities

3

CRG

The longitudinal approach allowed them to observe how the relative emphasis on the four boundary spanning processes shifted over time.

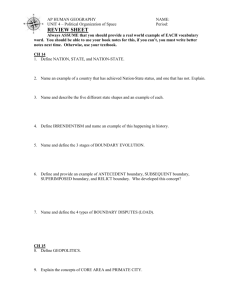

Three Contributions

The first contribution deals with the typology and the contingent approach to boundary spanning units in MNCs: Scouting units can do more than channeling information and knowledge!

The second contribution aims at showing how the cognitive and relational assets held by the boundary-spanning unit allows it to perform more value-adding boundary spanning processes, namely matchmaking and transforming processes.

The third contribution is about the dynamic model of a boundary spanning unit and delineates how a scouting unit evolves over time and improves self-reinforcing mechanisms. A positive cycle of trust building and social capital accumulation is likely to occur but negative selfreinforcing dynamics are also possible.

Three Practical Implications

Managers may rely on different types of radars (e.g. accelerators, scouting units…). Above all, they have to carefully position these radars and wonder how to best manipulate the signals captured from them.

Managers have to build and nurture several dimensions of social capital. It is not only about how to be relational, but how to combine different dimensions of social capital (structural, relational and cognitive).

A major issue about boundary spanning units deals with hiring, promoting, and retaining scouts. E.g. What is the next step for scouts? Do they go back to the business units?

Discussion

Nicolas Lesca : How to source information or knowledge is also a great issue in IT systems field. My research focuses on the organizational aspects of information, systems and technologies concentrating on developing and implementing knowledge management and strategic scanning to enhance the collective capacity to anticipate unexpected and unpredictable changes in the external (or internal) environment. I am interested in designing and experimenting methods and systems to develop the managerial skills and the ability to detect, disseminate, share, interpret and make sense of weak signals and to support anticipation and decision making. Scanning weak signals is particularly useful in relation to three moments of the strategic decision: triggering phase, development phase, and implementation.

First, I’d like to recall that the concept of boundary spanning is an old one. Thus, I wonder if new results can really be found. Then, I will underline similarities and distinctions between scanning and boundary spanning. In your article, you talk about information, knowledge, and even intelligence. In the scanning field, we refer to information, but in the literature on boundary spanning the notion of knowledge is used. According to you, are those three notions synonymous? I have also two questions about the validity of the work: What are the core competencies to identify and hire an efficient « scout »? What occurs when the scout leaves?

Finally, I would try an analogy between boudary spanning and absorptive capacity (Cohen &

Levinthal, 1990). You propose the following definition: “ a boundary spanning unit is a

4

CRG specialized entity that mediates the flow of information between relevant actors in the focal organization and the task environment ” (p.8-9). The three key elements to this definition are:

(1) Boundary spanning is a specialized activity done by a unit on behalf of the organization as a whole, rather than being a distributed activity done by everyone. (2) “Mediate” refers to gathering, understanding, interpreting and translating information, which nature is likely to vary according to the specifics of the situation. (3) The flow of information is potentially in two directions - usually it is an outside-in movement, but there are some situations where boundary spanners will also share internal information with external actors. To challenge the actionnability of your work, I would ask to what extent the knwoledge transmitted back by scouters is finally used by decision-makers. And what are the success factors to develop boundary spanning units, and more precisely technological scouting units?

Felipe Monteiro : Boundary spanning is an old debate indeed, dating back at least to the

1970s. But it has only received sporadic attention in recent years. However, we need to connect better to more recent literature about external knowledge sourcing.

About the controversy between information vs knowledge, I think we have been loose in our definitions of information and knowledge; we will work on that.

Rémi Maniak

: I have discovered your work 18 months ago, and I warmly thank you because it really helped me and my colleagues in our research. We are involved in a study analyzing the empowerment of several research scouting units, both in SV and France. And we were very puzzled. Most of the available research were “a-organizational” and roughly model local knowledge as sticky and the unit as sending knowledge which then flows in the large company… But this is absolutely not what we observed in the cases that we studied! They are not just scouting and sending opportunities because if they stick to this job, they would rapidly get overwhelmed. They would get lost in too many opportunities, so they have to learn to better identify what is a real opportunity for the parent company. They have to build a local social capital, a filtering capability, and a translating capability. And they would get lost since they broadcast the opportunities to the whole company's members, and they get tired of reading generic newsletters talking about fuzzy opportunities coming from far way. It takes time and efforts understanding the needs of the parent companies and building legitimacy towards certain units. That are the reasons why I were very enthusiastic by reading your PhD thesis which gives many details about the empowerment of a scouting unit, the mechanisms behind it, etc.

I have four questions.

1/ How can we speed up this empowerment?

You identify resources and routines which the unit has to build in order to achieve its full efficiency. But you do not really explain the ways the company could do it, or better, or efficiently.

2/ How does the mission evolve over time?

There is somehow a contrast between the initial motivations for having such units, and finally what comes out of them. Maybe these are not in the domains which were defined as target at the beginning? Is there also a mechanism of serendipity regarding the framing of the mission of the scouting unit?

3/ Have you thought about other relevant theoretical framings?

For instance, reviewers asked us to rely on the “economy of proximity”. At some point, you point some works in strategic management literature (cf contingencies and capabilities). The

Resource Based View and Dynamic Capabilities literatures could maybe be also useful.

4/ To what extent your framework can apply to more diverse innovation structures?

5

CRG

When talking about global R&D management, we always face the same question: what is specific to international? Any Lab suffers from this type of problems, trying to connect their

“research-oriented solutions” to the “development-oriented problems”. In an article we published last year in the Journal of Product Innovation Management , we described the roles of “advanced engineering units” as boundary spanners between research and development. So my question is: what part of your thinking and results are applicable to more generic R&D activities, and what are those specific to global R&D?

Felipe Monteiro : I really appreciated your comments.

Florence Charue-Duboc : Open innovation literature considers that sourcing external knowledge is all about channeling. Your work really adds to the debate by precisely distinguishing channelling from other processes and underlying the various competencies required an enable to understand and recognize… We can imagine that these units supported the building of these individual competencies but that it supported a collective and organizational learning process. You don’t underline it in your contributions despite but it is a very original part of the work since the social capital notion is primarily a notion related to a person.

Felipe Monteiro : In the quantitative paper, we have separated the individual and collective levels empirically. We have to insist in the paper on the fact that social capital is not only an individual attribute and how organizations can create social capital.

Participant: Do you really need an in-house structure? Would it be possible to rely only on partners there, such as business incubators, accelerators, etc.?

Felipe Monteiro : It is a great question: what part of scouting can be outsourced?

Romaric Servajean-Hilst : You said that the place where the scouting unit is localized is really important. The human factor is very important in boundary spanning activities. How did they achieve to transfer knowledge and to renew the team?

Nicolas Lesca : What could be said for smaller companies?

Felipe Monteiro : Understanding how the big guys work is very fruitful for small companies!

Then it is very difficult to have a specialized entity for small enterprises. The luxury of specialization is for big companies!

To go further

Lesca, H., and Lesca, N. (2014). Scanning the Business Environment and Detecting

Weak Sign. ISTE Ltd and John Wiley & Sons, London.

Lesca, N., Caron-Fasan, M.-L., Falcy, S. (2012). How Managers Interpret Scanning

Information. Information and Management , 49(2), 126-134.

Maniak, R., Midler, C., Beaume, R. and von Pechmann, F. (2014). Featuring

Capability: How Carmakers Organize to Deploy Innovative Features across Products.

Journal of Product Innovation Management , 31: 114–127.

Monteiro, F., Arvidsson, N., and Birkinshaw, J. (2008). Knowledge Flows Within

Multinational Corporations: Explaining Subsidiary Isolation and Its Performance

Implications. Organization Science , 19:1, 90-107.

Monteiro, F. (2015). Selective Attention and the Initiation of the Global Knowledge

Sourcing Process in Multinational Corporations. Journal of International Business

Studies , 1-23.

6

CRG

Next workshop

The next seminar will take place on 16 th

April at Ecole des Mines de Paris with Sihem Jouini,

Florence Charue-Duboc, and Christophe Midler who will present their book: Management de l’innovation et globalization : Enjeux et pratiques contemporains

7