View/Open

advertisement

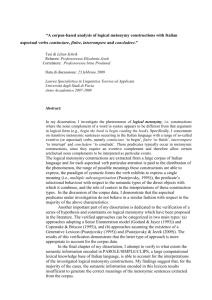

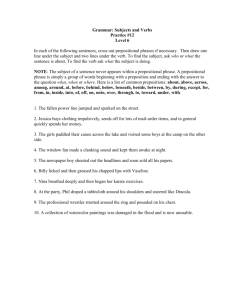

Multiple sources in the copularization of become Peter Petré Functional Linguistics Leuven (FLL) Research Foundation Flanders (FWO Vlaanderen) SLE 43 – 2-5 September 2010 Vilnius Introduction Overview • Introduction ◊ Topic ◊ Multiple source constructions and thresholds ◊ English Copular Construction ◊ Productivity ◊ Corpus • Copularization of becuman ◊ Productivity history ◊ Result Construction ◊ Depictive Construction ◊ Analogy with weorðan ◊ Influence from French • Conclusions Introduction Topic • Development of Old English (OE) becuman (Present Day English [PDE] become) from its original sense ‘arrive’ to the sense ‘become’. Wit becoman to ðam walle ‘we arrived at the wall’ Þa bi-com his licome swiðe feble ‘then became his body very weak’ • Becuman became a generally productive copula (could combine with a great variety of Subject Complements) in a fairly short period of time (ca. half a century). • Research question: How to account for this sudden development? Introduction Multiple sources and thresholds • "Sudden" turnovers like the copularization of becuman have been taken as evidence by generative linguistics that language change is 'catastrophical' reanalysis between generations (Lightfoot 1979, 1999); • This view has been criticized by more data-driven linguistic approaches (e.g. Warner 1983, Traugott 1989); • Hypothesis: there is a different way to account for "sudden" changes: ◊ the copularization of becuman is the consequence of the coincidental convergence of a number of constructions ◊ this convergence causes the verb to cross a threshold of similarity (formally, functionally, and in terms of frequency) to the already existing generally productive copula weorðan ‘become’. ◊ Certain constructions involving becuman are recategorized as Copular Constructions. ◊ From that point on, becuman could be used productively as a copula. Introduction English Copular Construction • Construction Grammar (Goldberg 2006, Croft 2001) allows for a unified account of copulas, semi-copulas etc. • Become in, e.g., he became a teacher is considered a Copula on a par with be in he is a teacher. • The reason for this is that they are used in the same type of (languagespecific) construction, much like the verbs give, tell, show, offer each instantiate the polysemous Ditransitive Construction (see Croft 2003). • Importantly (especially from a diachronic point of view), the basic unit of analysis is the construction, and the label ‘Copula’ only applies in a derived way. Verbs used in a copular construction are still the same verbs if used in a different construction, such as the existential one (e.g., There are ghosts), but then they are no longer Copulas. Introduction English Copular Construction (2) • The (English) Copular Construction is a combination of form and meaning. NPNOM IntrV XP NOM Sbj<-agent;-volition> Cop<+aspect> SbjComp<+focus> Act of predication • Instead of designating an action, the Copular Construction describes a state or a change of state. • The verb used as Copula generally has only one profiled participant in its semantic frame (also if used in non-copular constructions), Introduction Types of Copular Constructions (A) Adjectival Copular Construction [[NP IntrV AdjP] [Sbj Cop SbjComp]] ◊ Your baby is adorable; His daughter Mary became insane. (B) Nominal Copular Construction [[NP IntrV NP] [Sbj Cop SbjComp]] ◊ He is a teacher; She became a writer. • Both of these can occur with copulas that either denote a change of state (become, turn) or not (be, remain). (C) The Prepositional Copular Construction: the Subject Complement is introduced by a preposition ◊ • The frog turned into a handsome prince; A mustard seed grew into a bushy tree. This construction is (in English) only found with copulas denoting a change of state. Introduction Locational Construction • Intransitive verb and a PP (or adverb) indicating a location ◊ They stood on a bridge; They arrived at the airport. • Not copular ◊ it has two participants (the Subject and a Locational Complement) ◊ Human Subjects appearing in this construction are in control of the situation or action predicated of them. • Functional and formal similarities to the Prepositional Copular Construction: ◊ Location Complement is similar to a Subject Complement in that both are in focus. (i) They didn’t stand on the bridge generally implies that they stood somewhere else. ◊ Second, the two constructions are formally similar, in that both show the presence of NP, IntrV, and a PP (which specifies the Subject’s circumstances). Introduction Productivity • A central concept is that of syntactic productivity (Barðdal 2009). • Two dimensions: ◊ high type frequency ◊ semantic coherence • Hence General and Analogical Productivity. • Both types share: ◊ extensibility of the syntactic construction in question ◊ syntactic (formal) regularity of the extensions • Differences: ◊ GENERAL PRODUCTIVITY: productive through high type frequency ◊ ANALOGICAL PRODUCTIVITY: productive through analogical extension from one concept to a semantically related one (semantic coherence) • Analogical Productivity may shift into General Productivity. Introduction Corpus • LEON-alfa, ca. 2 million words (Petré 2009, 2010); • Used for calculating normalized frequencies pmw; • LEON-alfa tries to enhance comparability between OE and ME by reducing West-Saxon predominance (e.g. of Ælfric) and by introducing more Anglian material in the OE part, and by introducing southern material in the ME part (e.g. the Winteney version of Benedictine Rule). • Sources for additional data: YCOE, PPCME2, DOEC, MEC, HC, Arngart (1968), MED and ICAMET 2004, LAEME 2.1 Copularization of becuman Introduction • Before 1150 highly frequent in the sense 'arrive' • General productivity in its copular functions starts ca. 1150 • Multiple source constructions: ◊ Attainment Construction (Heo becom to soþum wisdome ‘She attained to true ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ wisdom’) Result Construction (e.g., andetnysse becumeð to hæle ‘confession results in salvation) > Prepositional Copular Construction. Depictive Construction (e.g., he arrived breathless) Analogical weorðan –constructions ‘become’ Old-French devenir Copularization of becuman Productivity overview of becuman 7501050 [BECUMEÞ AdjP|NP] 0 10511150 7 11511250 165 12511350 173 13511420 220 14211500 70 Table 2 & Figure 1: Copular becuman, pmw & productivity 80 1251-1350 70 60 1351-1420 50 1421-1500 40 1151-1250 30 Types per 100 tokens x Productivity rate 20 (Baayen & Lieber 1991) 10 750-1150 0 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 Multiple sources: Result Construction Locational Construction • • • • Original sense: 'arrive' 84% with Locational Complement (Locational Construction) 76% with animate Subject ([+Control], [+Volition]), as in (4) Inanimate Subjects linked to animate source already readily occur (3) (3) Cleopung min to ðe becyme. call mine to you come:SBJV.3SG ‘[May] my call come to you.’ (c825. PsGlA [Kuhn]: 101.1) (4) Wit becoman to ðam walle. we.two arrived at the wall ‘We two arrived at the wall.’ (c925. Bede 5: 13.428.32) Multiple sources: Result Construction Attainment construction (1) • Subject attains to or reaches a certain state: [[NP becuman to NP] [Sbj attain to <state>]] • Based on REACHING A STATE IS ARRIVING AT A LOCATION metaphor (Radden 1996: 435). (5) Se ðonne to halgum hade becymð. he then to holy hood comes ‘He then will come/reach to holiness.’ (c894. CP: 2.31.22) (6) Heo soþlice becom to soþum wisdome. she truly came to true wisdom ‘She truly attained to true wisdom.’ (c1025. ÆLS [Thomas]: 351) Multiple sources: Result Construction Attainment construction (2) • The Attainment Construction is linked to the Adjectival Copular Construction via conceptual metonymy: those who attain to holiness become holy. • Still clearly distinct: "changes of state based on this schema are understood as taking a regular course which gradually leads to an almost predictable outcome. Ideally, these changes of state are conceptualized as entities moving to the end of their paths." (Radden 1996: 435) -> the state reached is not a predicated property of the Subject, but is construed as a second participant, a destination that is reached. • At best, conceptual proximity between Attainment Cxn and Adjectival Copular Cxn may have made the leap to Copular Constructions cognitively more accesible. Multiple sources: Result Construction Happen to Experiencer Construction • Itself based on Locational Construction via metaphor: UNCONTROLLED EVENTS ARE EVENTS THAT FALL ON ONE (see Lakoff 1987; Radden 1991: 18). • Has inanimate Subject and animate Experiencer (12)Seo þearlwisnis þæs heardan lifes him ærest of nede becwom the austerity the:GEN hard:GEN life:GEN him first of need came for bote his synna. for amendmenthis:GEN.SG sin:GEN.PL ‘The austerity of hard life came upon him first out of necessity for the amendment of his sins.’ (c925. Bede 4: 26.350.1) Multiple sources: Result Construction Result Construction (1) • Pivotal construction in copularization process. • Obligatory: an inanimate Subject, becuman, an experiencer in the Dative (underlined in the examples), and a PP (introduced by to) expressing a certain state (in regular typeface). (8) Seo lease wyriung becymð þam rihtwisum. to eadigre bletsunge. the empty curse comes the:DAT righteous:DAT to happy blessing ‘The empty curse turns to the righteous into a happy blessing.’ (c1020(c995). ÆCHom I, 36: 495.258) (9) Swa þeah ne bescyt se deofol næfre swa yfel geþoht into þam men so though NEG shootsthe devil never so evil thought into that man þæt hit him to forwyrde becume, gif hit him ne licað. that it him to destruction come:SBJV.PRS.3SG if it him NEG pleases ‘Yet in that way does the devil never inject an evil thought in that man, that it would turn to him (in)to destruction, if it does not please him.’ (c1025. ÆIntSig: 41.259) Multiple sources: Result Construction Result Construction (2) • Only found in later Old English, from Ælfric’ texts (late tenth century) onwards • Probably represents a genuine diachronic development within Old English. • May be accounted for as a syntactic blend of: ◊ Attainment Construction: contributes PP expressing state reached; ◊ Happen to Experiencer Construction: contributes inanimate Subjects & Dative Experiencer Multiple sources: Result Construction Result Construction (3) • Result Construction is the first construction to combine an inanimate Subject (as inherited from the Happen to Experiencer Construction) with a PP expressing an end state. • This co-inanimacy enables their identification, and the shift of the construction towards one-participant predication. • Such an identification indeed seems to have taken place in very late OE: (13)Seo andetnysse þæs muðes becumeð þære sawle to hæle. the confession the:GEN mouth:GEN comes the:DAT soul:DAT to salvation ‘The confession of the mouth will result/turn for the soul into salvation.’ (c1150. Alc [Warn 35]: 322.230) (14)Ore autem confessio fit ad salutem mouth:ABL but confession turns into salvation ‘Yet confession through the mouth turns into salvation.’ ((799x800). ALCUIN. Virt.vit. 12: 621C) Multiple sources: Result Construction Result Construction (4) • Final step to Prepositional Copular Construction: loss of Dative Experiencer (15)Þas tintrego þe ðu on me bringan hehst to þinre thosetortures which youon me bring calls to your ge<s>cyndnesse & to þinre forwyrde becumað. confusion and to your destructioncome ‘These tortures which you command to bring over me will turn/result into your confusion and into your destruction.’ (c1051. LS 4 (Christoph): 26.19) (16)Seo sibb, þe on deofle is, heo becumð to ecere forwyrde. the love that in devil is it comes to eternal destruction ‘The love that is in the devil, it will turn/result into eternal destruction.’ (c1150. Alc [Warn 35]: 117.90) Multiple sources: Result Construction Result Construction (5) • Result: formal and functional equivalence to Prepositional Copular Cxn (17)He ys geworden nu to wealdgengan & þæra sceaðena he is turned now into thief and the:GEN.PL criminal:GEN.PL ealdor. leader ‘He has now turned into a thief and a leader of criminals.’ (c1075. ÆLet 4 [SigeweardZ]: 1107) • Consequence: recategorization & actualization (18) Þii fader bi-com to one childe. ‘Your father turned into a child.’ (c1250. Seinte marie leuedi [Trin-C B.14.39]: 28.14) Multiple sources: Depictive Construction Depictive Construction • Provides a template for Adjectival Copular Construction. (19) I parked, ran to the station and arrived breathless to the platform. (Google) • Old English examples: (i) Us milde bicwom meahta waldend æt ærestan þurh þæs engles word. ‘ The wielder of powers for the first time came to us (being) merciful through the word of the angel.’ (c970. Christ [Exeter]:26.820) (21)Eft ða se ylca. clypode to criste. Gemun ðu min drihten. again thenthe same said to Christ remember you my lord þonne ðu mihtig becymst. to ðinum agenum rice. roderes wealdend. when you mighty become to your own kingdomsky:GEN ruler ‘Again the same one said to Christ: Remember (me) you, my Lord, when you arrive mighty at your own kingdom, ruler of the sky.’ (c1000. ÆCHom II, 14.1: 146.253) Multiple sources: Depictive Construction Differences with Copular Cxn • Verb does not have a linking function; • Quality designated by the Depictive Phrase does not result from the change of location expressed by becuman/does not generally depend on the arrival (see Goldberg & Jackendoff 2004: 536). • Sometimes, however, it does (e.g., (21)): ◊ the relation of arriving and being mighty is one of temporal sequentiality ◊ a causal link between the arrival and the property may be pragmatically inferred (cf. e.g. the development of since from ‘after’ to ‘because’ (Hopper & Traugott 2003: 82). Multiple sources: Depictive Construction Source of Copular Cxn • The earliest instances of the Nominal Copular Construction contain the collocation becuman man, which could mean two things ‘(i) become a vassal; (ii) become human’. • Both these senses are compatible with a sense of arrival, and man might have been originally a Depictive. (23)Ða Wyliscean kingas coman to him & becoman his menn. the Welsh kings came to him and became his men ‘The Welsh kings came to him [= king Henry I] and became his vassals (arrived (being) his vassals).’ (?c1120. ChronH [Plummer]: 1114.20) (24)Soð god bicom for ure helpe soð mon. true god became for our help true man ‘True God became, for our aid, a real man.’ (a1225(OE). Lamb.Hom.VA [Lamb 487]: 127) Multiple sources: Analogy with weorðan Introduction • Result Construction > Prepositional Copular Construction • Depictive Construction > template for Adjectival Copular Construction • Important additional ingredient to reach general productivity: ◊ Analogical model of weorðan 'become' ◊ Serves as a template, which is copied by becuman once becuman has reached a certain degree of similarity with weorðan. ◊ Becuman in this way is recategorized as a Copula (categorical incursion, see De Smet 2009) Multiple sources: Analogy with weorðan Initial similarity • Already from the start becuman and weorðan: 'happen' (26)Swa hwæt swa he gecwyð, hit becymð and gewyrð. so what so he says hit comes and happens ‘Everything he says, it will come/happen and happen.’ (c1000. ÆHom 8: 91) • This similarity is too limited to trigger analogical copying. Multiple sources: Analogy with weorðan Evidence for analogy (1) • In the 12th century the Result Construction with becuman shifted to a oneparticipant cxn, becoming equivalent to a Prepositional Copular Cxn. • Some extensions, like those with animate Subjects, are still not obvious. • Weorðan may have provided an analogical model. (27)To nane þinge ic eam bycuman, & ic hit nyste; swa swa to no thing I am come and I hit NEG.knew so as þat nyten ic eom ȝeworden toȝeanes þe. that beast I am become toward you ‘To nothing I am become, and I did not know it; in such a way that I have become a beast towards you.’ (c1225. BenRW: 7.39.7) (28)Hwi schuldehe forhohien to wurðen to þat þing þat is iwend upon him why should he disdain to turn into that thing that is formed on him ‘Why should he disdain to become/turn into that thing which is formed after him?’ (c1225(?c1200). St.Kath. (1) [Einenkel]: 992) Multiple sources: Analogy with weorðan Evidence for analogy (2) • The Result Construction with becuman also increased in frequency. • This may have facilitated the accessibility of an association with the Prepositional Copular Construction involving weorðan. • Once becuman was treated on a par with weorðan as potential lexemes in the Prepositional Copular Construction, other Copular Constructions (already prepared by the Depictive Cxn) become productively available as well. • Evidence is found in alternations such as: (34) Þe gastelich lif bigunnen i þe hali gast beoð bicumene al the spiritual life begun in the Holy Spirit is become all fleschliche, al fleschliche iwurðen lahinde, lihte ilatet, ... fleshly al fleshly become laughing light behaved ‘The spiritual life begun in the Holy Spirit has become completely carnal, become completely carnal: laughing, loosely behaved, ...’ (c1230. Ancr. [Corp-C 402]: 58.2) Multiple sources: French Language contact with French • Factor that may have helped Copular becuman; • Not a very probable direct cause, given general absence of loan translations. (35)E Gudlac mandé li aveit [...] Ke de Belin s’enor and Guthlac handedhimself had so-that of Belin his’praise tendreit, E sis huem liges devendreit. gain:SBJV andhis man liege become:SBJV ‘And Guthlac had handed himself over [...] so that he would gain the praise of Belin, and become his liegeman.’ ((c1155). Wace Roman de Brut: 2580-4) (36)Þeos swiken gunnen ride; [...] to Beline kinge. [...] & his men bicome. thesetraitors began ride to Belin king andhis men became ‘These traitors then rode; [...] to Belin King, [...] and became his vassals.’ (a1275(?c1200). Lay. Brut [Clg A.9]: 2728) Conclusions • A grammatical use of a verb may have multiple source constructions; • General productivity may emerge within a very short time span when a number of developments and phenomena co-occur and make becuman cross a threshold; • This type of account also explains the timing of that explosion; • In the case of becuman, general productivity occurred from the second half of the 12th century onwards. At this time: ◊ Depictives were around (as they had been for a while); ◊ Weorðan was around; ◊ The Result Construction had only just finished shifting into a Prepositional Copular Construction; ◊ French influence had only just started to be omnipresent. • A single lineage account has arguably greater difficulty in accounting for the timing of a development; • This leads to the question: how general is the multiple sources account? References Arngart, Olof (ed.). 1968. The Middle English Genesis and Exodus (Lund Studies in English 36). Lund: Gleerup. Baayen, Harald R. & Lieber, Rochelle. 1991. Productivity and English derivation: a corpus-based study. Linguistics 29. 801–843. Barðdal, Jóhanna. 2009. Productivity: Evidence from case and argument structure in Icelandic. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Croft, William. 2001. Radical Construction Grammar. Syntactic theory in typological perspective. Oxford: OUP. Croft, William. 2003. Lexical rules vs. constructions: a false dichotomy. In Hubert Cuyckens et al. (eds.), Motivation in language: studies in honor of Günter Radden, 49-68. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. De Smet, Hendrik. 2009. Analysing reanalysis. Lingua 119. 1728-1755. DOEC: Dictionary of Old English Corpus. http://www.doe.utoronto.ca/pub/corpus.html (19 January 2009). Goldberg, Adele & Ray Jackendoff. 2004. The English resultative as a family of constructions. Language 80(3). 532-568. Goldberg, Adele. 2006. Constructions at work: the nature of generalization in language. Oxford: OUP. HC: Helsinki Corpus of English Texts: Diachronic Part, 2nd edition. 1999. Matti Rissanen et al. Helsinki. Hopper, Paul J. & Elizabeth C. Traugott. 2003. Grammaticalization, 2nd edn. Cambridge: CUP. ICAMET 2004: Innsbruck Middle English Prose Corpus (sampler). http://anglistik1.uibk.ac.at/ahp/projects//icamet/prose_corpus/index.html (19 January 2009). LAEME 2.1: A Linguistic Atlas of Early Middle English, 1150-1325 [http://www.lel.ed.ac.uk/ihd/laeme/ laeme.html] compiled by Margaret Laing & Roger Lass (Edinburgh: © 2007- The University of Edinburgh). Lakoff, George. 1987. Women, fire, and dangerous things: what categories reveal about the mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. References Lightfoot, David. 1979. Principles of diachronic syntax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Lightfoot, David. 1999. The development of language: Acquisition, changes and evolution. Oxford: Blackwell. MEC: Middle English Compendium. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/c/cme/ (19 January 2009). MED: Middle English Dictionary. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/med/ (19 January 2009). Petré, Peter. 2009. Leuven English Old to New (LEON): Some ideas on a new corpus for longitudinal diachronic studies. Presented at Middle and Modern English Corpus Linguistics (MMECL), Innsbruck. Petré, Peter. 2010. On the interaction between constructional & lexical change: Copular, Passive and related Constructions in Old and Middle English. Leuven: Unpublished PhD thesis. PPCME2: Anthony Kroch & Ann Taylor. 2000. Penn-Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Middle English, second edition. http://www.ling.upenn.edu/hist-corpora/PPCME2-RELEASE-2/ (31 March 2009). Radden, Günter. 1991. The cognitive approach to natural language. Duisburg: L.A.U.D. Radden, Günter. 1996. Motion metaphorized: The case of coming and going. In Eugene H. Casad (ed.), Cognitive linguistics in the redwoods: the expansion of a new paradigm in linguistics (Cognitive Linguistics Research 6), 423-458. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Traugott, Elizabeth C. 1989. On the rise of epistemic meanings in English: An example of subjectification in semantic change. Language 65(1). 31-55. Warner, Anthony. 1983. Review of Lightfoot, Principles of diachronic syntax. Journal of Linguistics 19. 187-209. YCOE: Ann Taylor et al. 2003. The York-Toronto-Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Old English Prose. York: Department of Language and Linguistic Science. YPC: Susan Pintzuk and Leendert Plug. 2001. York-Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Old English Poetry. 2001. York: Linguistics Department. Contact information Peter Petré Department of Linguistics University of Leuven Blijde-Inkomststraat 21 B-3000 Leuven, Belgium Email: peter.petre@arts.kuleuven.be http://wwwling.arts.kuleuven.be/fll Link to presentation: http://perswww.kuleuven.be/~u0050685/2010_Petre_SLE43.ppt