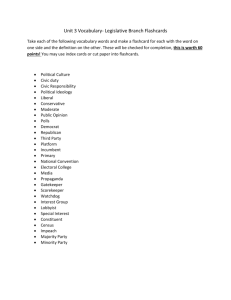

Flashcard Project for 5710

advertisement

Once my Kindergarteners have alphabet knowledge under their belt, I begin sending home flash cards with sight words on them. We have used flashcards in our classroom for many years and have seen the benefits from their use. The goal of this study was to gain knowledge from the research done on the effectiveness of flashcards. We hoped to find great conclusions from our studies so we would be able to back up our stand on how important flashcards are in helping students to be able to recognize sight words with automaticity as well as greatly increase their sight word bank. Article #1 (Julie Dalton) Nicholson Tom. (1998). The flashcard strikes back. The Reading Teacher, 52 (2), 188-192. Are flashcards a useful technique? What is the proper way of using them? Do they really deserve a bad reputation? These are questions Nicholson wanted to investigate. The goal of this study is to find a good way to get unskilled readers to a point where they can recognize many words with automaticity, so they can start reading stories independently. Nicholson believes that flashcards can help a student achieve this goal. Good readers need to be able to identify high-frequency and irregularly spelled words in order to successfully read stories. A child’s comprehension is likely to be lost if they are spending too much cognitive energy struggling with each word. If these readers were able to read quickly and accurately, then they can devote their full mental energies to comprehension. “Good readers read words quickly and effortlessly” (Nicholson, 1998). Flashcards can foster automaticity by helping children to read words accurately and quickly. Some critics believe that flashcards teach children to “bark” at words in print. These critics don’t believe that rote learning will contribute to the bottom line of comprehension. But recent research suggests the opposite, that teaching children to read words faster can improve reading comprehension dramatically (Tan & Nicholson, 1997). This study found that a short 20 minute session of flashcard training, with 20 difficult words, will set up a struggling reader for a positive reading experience. They compared three matched groups of unskilled readers, aged from 7 to 10 years. The first group had training with one-word flashcards (example: raspberries). The second group had training with sentence flashcards (example: I like to eat raspberries). The third group, a control group, discussed the flashcard words verbally but did not read them. Each student in all three groups fully understood the meanings of all 20 words. The results of the flashcard speed and reading comprehension were interesting. The oneword flashcard readers read an average of 54wpm with 74% comprehension. The sentence flashcard readers read an average of 65 wpm with 80% comprehension. The control group readers read an average of 26wpm with 42% comprehension. The students were also tested to see if they could recall the passage using main ideas and details. The one-word flashcard readers achieved this with 54% accuracy. The sentence flashcard readers achieved this with 80% accuracy. The control group readers achieved this with 30% accuracy. The results stated that no significant differences were found in speed of word reading or comprehension between the two flashcard training groups (one-word and sentence). Although they were significantly better than the control group, both for speed, reading flashcard words, and for comprehension. Tan and Nicholson (1997) found no difference between either type of flashcards in terms of effectiveness. Each student in the study knew the meaning of the 20 flashcard words. The students who could read these words quickly are the ones who improved in speed and comprehension. The article also states that 100% of the students involved in the reading of the flashcards enjoyed their lesson. This can easily be done in any classroom. Pick 20 words from a book the student is getting ready to read. Write each word or a sentence containing each word on an index card. Present each of the 20 cards, one by one to the student. See if the student can recognize them. If not, pronounce the word and check for meaning. If a single-word flashcard is being used, write a sentence or phrase with the word on the back. If the student doesn’t not know the word’s meaning, turn around the card and show the sentence. Next, ask the student to use the same word in a sentence as well. The student needs to fully understand the meaning of the flashcard word. Work on this for 20 minutes. Once the flashcards are well learned, ask the student to predict what will happen in the book. Now it is time for the student to read the book aloud to you. Afterwards it will be time for him/her to answer some comprehension questions or retell the story. Taka (1997) obtained very similar results, using flashcards as part of a bingo game in another study. Taka worked with a small group of adult literacy learners. Each bingo card contained 25 words to be learned. The tutor shuffled the stack of 25 flashcards and called out the words one at a time. If the student had that called-out word on their bingo card, he/she would cover it up with a chip until someone called “BINGO”. As a result of this game, these students improved in word reading accuracy. The training also had a positive effect on their comprehension when they read stories that contained these trained words. This fun technique of using flashcards with a bingo game made the once difficult story easier for the troubled readers. Taka (1997) reported that the students really enjoyed the bingo games. Flashcards can be a useful technique when used properly. They can make a poor reader a better reader. Teachers need to also understand that excessive drilling in long sessions will turn students off to reading altogether. Giving the students a purpose with these words makes more sense. Allowing them to understand each word and then having them see these words in print makes it all worth while. Flashcards can promote fluency and in turn help gain comprehension. Flashcards can also be a lot of fun when used properly and sensibly in small doses. Article #2 (Julie Dalton) Tan, Annette, and Tom Nicholson. "Flashcards Revisited: Training Poor Readers to Read Words Faster Improves Their Comprehension of Text." Journal of Educational Psychology. 89.2 (1997): 276-288. Will teaching struggling readers to read words faster improve their comprehension? A reader must use a variety of cognitive processes such as word recognition, word meaning, evaluating sentences as well as comprehension of the entire text. For experienced readers, these processes are automatic. It takes several years to become a skilled reader. Beginning readers will not have the speed and fluency of skilled readers. Fluent word recognition usually comes after a long period of extensive reading practice. In this study, the authors inferred that a focus of automatic word recognition skills would most likely have positive effects on poor readers’ comprehension. Word recognition is one part of the reading process that is very difficult for beginning readers. LaBerge and Samuels’s (1974) model of automaticity in reading was the theoretical rational for this study. They argued that in order to become a proficient reader, close attention is first needed in order to recognize words. If word recognition consumes too much mental attention, then the extra effort taken in recognizing words will hinder comprehension. There were 42 students in this study (24 boys and 18 girls). Within the 42 students, twelve of them were age 7, twelve were age 8, nine were age 9 and nine were age 10. The students were all from the same low-income school in Auckland, New Zealand. The students selected came from a group of 54 children who were identified, by the school, as below-average readers, based on their performance on an informal inventory. With further screening and other reading tests, twelve students were dropped from the group, leaving a final group of 42 students. The main pretest screening came from the Neale Analysis of Reading Ability (Neale, 1989). This test measured reading comprehension, reading rate, and reading accuracy levels. This test consisted of six graded passages for use in assessing students in the 6-12 year age range. Each passage was read orally by the student. Each student was then asked a set of comprehension questions. The students were also assessed for phonemic awareness using the Roper test of phonemic awareness (Roper, 1984). This test involved segmentation. The final screening measure was the Bryant Test of Basic Decoding Skills (Bryant, 1975). The purpose of the screening test was to select three matched groups. This was done in two phases. First, students within each chronological age group who had similar comprehension scores were assigned to matched triplets. Each student in the triplet was then randomly assigned to one of three conditions: single-word training, sentence training, or a control condition. Each condition contained the same number of students at each chronological age and by similar reading levels. Each student was given five training sessions. Each session lasted about 20 minutes. Each student was trained and assessed individually. There was no group training or assessment. Each session focused on words from a single story. The five sessions covered 5 stories. Since there was a range of ability and age levels within each group, 25 different stories were used. The words to be trained varied in number. The trainer selected 7-8% of the total number of words in the passage. The word lists ranged in number from 10 to 25 words. Twelve comprehension questions were given for each passage. Eight questions were factual and 4 were inferential. The factual questions could be answered simply by remembering what was in the passage. The inferential questions required the students to combine text details with their own general knowledge. This caused the students to have to make inferences and draw conclusions. In the single-word training, each student was taught to recognize each target word by using flashcards that were printed on an index card. The student was asked to read the word aloud. If the student could not read the word aloud, the card was flipped showing the student a short phrase. For example, the front of the card might read lemonade. The back of the card might read lemonade drink. The phrases on the back of the cards were not taken from the context of the passage to be read. The student was also taught the thumb-across-the-word method. This method teaches the student to read aloud one bit of the word at a time. These short context cues were given only when the student had trouble with the meaning of the word. The flashcard training continued until the student could recognize each word on each card in approximately 1 second. This normally happened during a single 20 minute training session. Afterwards, a word list containing the target words from the index cards was given to the student. The student was asked to read the words as fast and accurately as they can. If the student was unable to read the list of words extremely quick and accurately, index card training would continue until the list of words could be read a second per word. Once the word list was mastered, the student was given the passage from which the target words had been taken and asked to read it aloud. The time to read the passage and the number of errors made were both recorded. Twelve comprehension questions relating to the story was asked for the student to respond to orally. All responses were recorded. The session ended by asking the student to retell the passage that was just read orally. In the phrase training condition, the students were shown mostly phrase cards containing the target words from the passage they were later to read aloud. Each phrase was designed to show the meaning of each target word. The trainer made sure that none of the phrases came from the text passage or from the questions that followed the passage. The target words were not underlined or highlighted. The student was not told which word was an important word to focus on. Students practiced reading these phrases during a 20 minute training session. The goal was for the child to read these words at a rate of 90 words per minute. Afterwards, the student was given the word list of target words to read accurately and quickly. The students were given the passage that corresponds to the target words studied to read aloud. Comprehension questions and retell of the passage was also asked and recorded. In the control condition, the students were trained for the same amount of time. The target words were each read aloud to the student. The student was then asked to explain what the words meant. After listening to and discussing the words for 20 minutes, the student is given a random list of the words that had been discussed and then was told to read them as quickly and as accurately as possible. Only one list was given to these students. Each student was then asked to read the corresponding passage, answer questions and retell what he or she could remember about it. The control students were exposed to the same words, taught for the same amount of time, and were able to discuss the meaning of the words as the other two groups of students. At the end of each of the five training sessions, each child is the study was given a questionnaire which included questions of how well they enjoyed the sessions. The results showed that children in the two trained groups were not only faster but also more accurate than the children in the control groups. For each child the authors calculated the number of list items correct and then checked to see how many of the correctly read list items were also read correctly in the corresponding passage. They then calculated the percentage of correct list words that were also read correctly in passages. With this, they were able to compare relative accuracy of list reading with relative accuracy of passage reading just for those items that each child had read correctly in lists. The trained students had learned the list words so well that they were able to transfer their list reading skills to the passages more effectively than were the control group. The findings suggest that even if all three conditions had achieved similar levels of accuracy in the reading of list items, the control condition would still not have done as well as the training conditions in passage accuracy because they had not experienced the benefits of the extensive speed training. The results of the study states that students who received word training (single or phrases) significantly outperformed the control group on all measures of comprehension. These findings were different than those of Fleisher (1997). He found that reading comprehension scores of a group of trained poor readers did not benefit from rapid decoding training, compared with a group of untrained poor readers, even though the trained students were faster and more accurate in their reading of trained words. It seemed that the training emphasis on accurate and quick word reading was more important for improved comprehension than was accuracy on its own. The trained students had seen a list of words so many times that they had it internalized into their memory. Extensive drill and practice of meaningful words can be an effective means of relieving the reading process. The phrase flash word and single flash word groups had similar speed and accuracy of word recognition. It appears that there was enough time in each training group to reach the speed accuracy criterion, as well as gain word meanings. This would not have been the case without the proven gains in speed and accuracy of word recognition that came from the flash card training. There was much lower comprehension scores for children in the control group. This control group also received instruction in word meanings but was not trained in rapid decoding. Extensive drill and practice with word training supports the arguments of Gilbert, Spring, and Sassenrath (1997) and Bloom (1986), that over learning is necessary in the development of automaticity. The authors found that student’s ability to recognize words improved rapidly with practice. The use of flashcards should be used to supplement the teaching of phonemic awareness skills and letter-sound relationships. Flashcards alone will not provide the basic skills required to become a good reader, although it is possible that they will improve speed and accuracy of specific word recognition (Lovett, Warren-Chaplin, Ransby, & Borden, 1990). Students must first gain the ability to decode words. Then flashcards could be extremely helpful when provided opportunities for practice and over learning. This is necessary for making progress in reading. In conclusion, the present study provides support that fast decoding as an important factor, although not the only factor, in explaining the difference between good and poor reading comprehension. The results of this study also support instructional strategies that offer opportunities to develop speeded word recognition. Article #3 (Julie Dalton) Mechling, Linda, David Gast, and Kristin Krupa. "Impact of SMART Board Technology: An Investigation of Sight Word Reading and Observational Learning." Springer Science Business Media. 9 March 2007: 1869-1882. Print. Computer-assisted instruction (CAI) has been used to teach students with disabilities since the mid 1970’s. This has been shown to increase motivation, attention, and time on task by giving interactive instruction with sound, animation and video recordings. In the past, the CAI was used by one student at a time by delivering instruction in a lab format. It has been shown that students with disabilities can learn through CAI, learn in small groups and acquire information through observational learning. Instruction delivered via computer to a small group of students has not been examined. One reason may be the difficulty the students would encounter by trying to view the one and only small computer monitor. The current study looked at the presentation of information on a large screen in an interactive format to teach sight words within a small group. This study addressed the following research questions: Would the SMART Board technology taught within a small group result in students being able to read target grocery words? Would the students be able to match the grocery photos to the target words? Will they be able to read other students’ target grocery words through observational learning? Three students (2 males and 1 female) with moderate intellectual disabilities participated in the study. They were selected based on their IEP objectives. These objectives included increasing functional sight word vocabulary. Students were screened for their visual ability to see the photographs and text on the screen, matching of photographs, word matching, verbal imitation and being able to have a wait response of 3 seconds. These three students were enrolled in a local high school Transition Program for Young Adults which is designed to support transition from school to community. Sandy was a 20 year old female diagnosed with a moderate intellectual disability (IQ 54). She is very social and liked to assist other students. She was able to read simple personal care directions, job related words and recognized 33 “survival” signs. She could tell time to the hour, operate her personal cell phone and use the public bus system. Her needs included purchasing items using the next dollar strategy, comparing prices, following picture and word recipes, grocery shopping using a word list and identifying desired employment. Sue was a 19 year old female diagnosed with Down Syndrome and moderate intellectual disability (IQ 53). She spoke quietly in clear and complete sentences. She can read the weekly class newspaper, 60 job related words, and short stories written on a second to third grade level. She was able to spell three letter words, write her first and middle name and copy from the board. She could locate personal care items in a store and purchase snacks in a vending machine. Her needs included counting mixed bills, speaking in a loud tone, reading recipes, measuring small amounts of ingredients, grocery shopping using a word list and locating and reading labels on clothing. Andy was a 19 year old male diagnosed with Athetoid Cerebral Palsy and has a moderate intellectual disability (IQ 52). He reads on a third grade level, reads the newspaper and answers factual questions. For mobility he uses a manual wheelchair, posterior walker, and a power scooter when in the community. He can type answers to questions, thank you notes, and letters with up to three sentences using a computer. He wears a watch and is able to tell time. He frequently speaks about one topic (cars) and repeats questions during conversations. Previously he had been employed at the YMCA handing out towels and greeting guests at the front desk. His needs included slowing his rate of speech and speaking clearly, safely using a motorized scooter, locating clothing and shoes in stores, locating 5-6 items in a grocery store from a written list and staying on topic during conversations. The study sessions took place in a classroom that the three students were familiar with. During the CAI sessions, the three students sat in a horizontal row approximately 2 feet from the front of the SMART Board. Thirty-five multi-syllabic and compound words, unknown to all students, were identified from a screening list of 70 grocery words. During screening, words were presented individually to students on PowerPoint slides using the SMART Board. The assessor would ask each student during each slide, “What word?” Students were unable to read the 35 words on three consecutive screening sessions. Twenty-seven grocery words were then selected from the list of 35 unknown words. This final selection was made by presenting photographs and asking students, “What do you buy at the grocery store?” Words in 14in Times New Roman font (lower case) were presented one at a time on PowerPoint slides during the sessions. Each slide contained the target word at the top middle and an arrow button on the bottom right side of the slide. The instructor used the arrow to advance to the slide of the four grocery item photographs. A slide of photographs containing the target word and photographs appeared immediately after the target word slide. One photo included on this slide was of the target word. The other three photos were of observational words or other target words. The photographs were positioned on each of the four corners of the slide with the target word centered in the middle of the slide. If the student touched the correct photograph, then the program advanced to the next target word slide. The arrow button was used by the instructor if the answer was incorrect. Three PowerPoint programs were created for each word set to mix the order of words and trial presentations across the three students. During the pretest/posttest sessions, student responses for reading printed words were recorded as correct if the student read the word within 3 seconds of the instructor presenting the slide. It was recorded as incorrect if the student said an incorrect word within 3 seconds of the slide being presented. It was recorded as no response if the student sat silent within the 3 seconds of the slide being presented. For the objective of identifying the picture to match the target words, the task of recording a response was the same as above. During SMART Board instruction, student responses for reading the target words could be recorded one of five different ways. An answer was recorded as unprompted correct if the student correctly read the word within 3 seconds and before the instructor’s question, “What word?” An answer was recorded as unprompted incorrect if the student said the incorrect word within the 3 seconds and before the question. An answer was recorded as prompted correct if the student said the word correctly but needed prompting. An answer was recorded as prompted incorrect if the student said the incorrect word after the 3 seconds and after the question. An answer was recorded as no response if the student failed to say anything within 3 seconds and after the verbal cue from the instructor. During the SAMRT Board instruction, student responses for indentifying or matching photographs to the target words were recorded similar to above. The student responses were recorded as unprompted correct, unprompted incorrect, prompted correct, prompted incorrect and no response. Small group instructional sessions were conducted each school day (M-TH) when all students were present. The SMART Board with the 3 second timed slides were used to teach students to read 9 target grocery words ( 3 sets of 3 words) to each student. Each student received 30 trials during each session (3 grocery reading words X 5 trials and 3 non-identify matching words X 5 trials). Each of the three PowerPoint programs was designed so that each student received one turn during each computer presentation of the three trials. Target words of the other students served as observational words. The first letter of the student’s name was placed in a small font at the bottom of the slide containing their target word. After presenting the task direction, “What word?”, the instructor immediately presented the target word slide. After the student read the word on their own or with help, the slide was advanced and the non-identity matching slide was presented. The student was told to, “Touch the picture that goes with the word” upon seeing a slide with four photographs and the printed target word. Sessions continued untimed until each student in the group reached 100% prompted correct responses for both naming and matching. On the remaining trials, a 3 second prompt delay was inserted between the presentation of the word and the prompt. Unprompted and prompted correct responses were followed by verbal praise and the instructor advancing to the next slide. Incorrect responses or no responses were followed by the instructor saying the correct word. The same teacher responses were administered for the matching of photographs to the target word. Prior to instruction, students were unable to read any of their target words and none of the students correctly matched more than 16.7% correct during any sessions with the exception of the first session when Andy matched 1 of 3 trials correctly. Results indicate increased correct reading and matching of each set of target words using the SMART Board with the 3 second timed procedure. All students reached criteria for each of their target sets of words. Criteria were reached within 6 sessions for each set of words. Sue correctly read and matched all of the target words during each condition at 98.4%. Andy maintained reading his target words at 95.2% across all sessions. Sandy read 96.8% of her target words across all conditions. This study also showed effectiveness of using the SMART Board technology and the 3 second timed slides when teaching students, in a small group, to read other student’s target grocery words and match grocery item photos through observational learning. All students learned other students’ target words by presenting instruction via the SMART Board. None of the students could read these words before the small group training. Sue read 100% and matched 97.2% of peer target words across all sessions following instruction. Andy read 86.1% and matched 88.9% of peer target words after instruction. Sandy had the lowest performance for reading other students’ words. She read 58.3% and matched 97.2% of peer target words following instruction. The study evaluated the use of a large screen and an interactive computer program to deliver instruction in a small group setting. This study is the first to demonstrate its use to teach multiple students at one time and investigate its effects on observational learning of non-target information. Results support the large screen for delivering target information and learning of other students’ information by making images more visible and increasing attention to the task. This study did state that not all students learned each non-targeted word that they were exposed to. When the time comes to teach that information directly, the student will acquire that information in less time and with fewer errors than information of comparable difficulty that were not exposed. Article #4 (Julie Dalton) Torgesen, Joseph, Mary Water, Andrew Cohen, and Jeffery Torgesen. "Improving SightWord Recognition Skills in LD Children: An Evaluation of Three Computer Program Variations." Council for Learning Disabilities. 11.2 (1988): 125-132. Print. This study was designed to investigate the effectiveness of three variations of a computer program that was designed to increase the word reading fluency of learning disabled children in the early elementary grades. The investigation is influenced from the finding (Stanovich, 1986) that the primary reading difficulties of many LD children lie at the word, rather than the text level. A high percentage of LD students have difficulty reading individual words rapidly and accurately. This difficulty interferes with the higher level of reading comprehension skills. A major goal for LD children in elementary grades is to help them develop the necessary skills to rapidly and accurately read individual words. Recent cognitive studies of children that decode individual words suggest that they apply at least three different methods, depending upon the word (Perfetti, 1984). Some words are decoded by closely looking at individual graphemephoneme relationships and constructing a blend of the “sounds” of the letters. This method is normally used with unfamiliar words. Another approach involves identifying familiar segments within unfamiliar words. For example, a student might read the word plant by recognizing the segment “ant” as a whole and blending the initial consonant “pl” with it. Finally, some words are read as whole units. These words are frequently referred as sight words. They are typically read more rapidly than words that must be decoded. Building a great reader involves instruction and practice in all three of these methods. In the present study, the authors focused on a method to increase the number of sight words in children’s memory. The researchers used technology as a means of delivering large amounts of practice without much teacher responsibility. This format also involved response speed that was closely monitored. Therefore the lesson mastery can be defined in terms of both speed and reading accuracy. Another advantage is that this method could be used to build beginning word-recognition skills in children who possess essentially no reading skills. The study focused on two major issues. The first one involves basic program effectiveness. The practice program required the child to choose among two or three words. The correct representation of a picture was presented on a computer screen. At first the authors were concerned about the different effects of three program variations. One variation (visual only) required the child to respond to a simple pictorial representation of the word. In another variation the child was provided with both a picture of the word and the pronunciation of the word. The third program version (auditory only) provided the child with the spoken word only. The authors were interested in determining whether one version would prove more effective for the group as a whole. They also wanted to determine if significant individual differences would emerge among the children. There were seventeen learning disabled children identified for participation in this study. Each child considered for this study must be in the first, second or third grade. They had to be included in LD classes and have a full-scale IQ score above 70. They also required that students be unable to correctly read more than 20% of the words to be taught in the study. The participating students’ average IQ was 94.2 and their average reading level was 1.8. The computer program used to present instruction and practice was called “WORDS.” This program provided two types of practice in identifying words in practice sets. Each set consisted of 10 words. Three phases or activities were involved. In the first, each word in a set was presented individually along with a picture that represented its meaning. This activity was designed to introduce the picture that would stand for each word. The child was to pronounce the word orally. The student was corrected only once if the picture was incorrectly identified. The children had no difficulty remembering the “names” of the pictures. The children also practiced typing the words into the computer. After all 10 words have been reviewed in activity 1, the child began activity 2. The computer presented the picture with two words below. The student had to choose the correct word and type it into the computer. The child had one chance to correct any errors. Activity 2 included three levels of practice. In the first level, distractor words were added. These words consisted of words from the same practice set as the target words. In level 2, the distractor words included began with the same first letter as the target word. In level 3, the distractor words began with the same first letter and were similar in length to the target words. To advance to a new level, the child had to achieve 90% accuracy at the previous level of practice. If the child missed 2 or more items, then they had to repeat the entire activity. Once the child was able to meet the accuracy criteria for all levels of Activity 2, the child completed a third activity. This activity used the same words in the practice set. The computer presented the picture of the word alone. Next the computer presented three words with the numbers 1,2,3 above them. The student had to type the number above the correct word. The three practice levels in this activity were organized just like Activity 2. The only exception was the use of different distractor words. To move between levels, the student had to respond with 90% accuracy within 3 seconds of each word. The item was scored incorrect if the answer was not reported within the 3 second time limit. After the child has met the criteria on all levels of Activity 3, the computer presented a videogame that involved the words in a practice set. This proved to be great reinforcement. The auditory versions of the program were constructed using the Mockingboard Speech synthesizer. Apple IIe microcomputers were used to run the program. The pronunciation was as close to human speech as possible. The speech did have a robot-like quality. None of the children reported consistent difficulties understanding it after being introduced. Data on speed and accuracy of reading the words practiced in the study were collected using the same computer as in the training. The computer presented the words individually in large, lower case text. A total of 80 words were used as stimuli. These words were taken from several different standard word lists. Most of the words were 2 and 3 syllable words to ensure that the children could not read them correctly at the beginning of the study. Words were randomly grouped into eight sets of 10 words each. The four treatment conditions (auditory-visual, auditory-only, visual-only and no treatment) were alternated on successive weeks. The students were exposed to the four conditions during cycles, so that they experienced each condition twice. The experiment took approximately 8 weeks. For each instructional condition (auditory-visual, auditory-only and visual-only), instruction took place using the “WORDS” program as outlined. In the no-treatment condition, the students worked on the computer with a math program that provided no instruction in reading. Following a day of orientation and the opportunity to practice using the “WORDS” program with words not included in the study, children were pretested on the first list of words. After the pre-test, the students spent 15 minutes a day working individually on the computer for 5 days. At the end of the last day of practice, the posttest was administered. It took 6 minutes to administer the pre- and posttest. Therefore, the students practiced each word set for approximately 65-70 minutes. The total time each child spent in each instructional condition was recorded. All three instructional conditions were equally effective in teaching the subjects to read individual words accurately. During the pre-test, 17% of the words were read correctly. During the posttest, approximately 70% of the words were read correctly. All three treatment conditions produced substantial increases in speed of responding. Such improvement did not occur in the no-treatment condition. It was important to look at the range of individual differences in response to the various treatments. Were the three treatment conditions equally effective for all children? The study shows that there were no obvious differences between treatment conditions in the number of children who made various levels of improvement. Every child’s average in the study increased in each treatment condition except for the no-treatment condition. In conclusion, the three versions of the program were equally successful in establishing accurate recognition of words in the practice sets. The children were able to successfully move from the practice format to the instructional format. This study validated that the mentioned software indeed improved learning with the disabled children’s reading skills. The authors do not recommend that programs like “WORDS” should be used in isolation from other elements of reading instruction. Ideally, the words introduced by the program should come from each child’s regular contextual reading. These words should also be presented and reinforced by reading the words in a variety of contexts. This will contribute to permanent improvements in children’s reading skills. Article #5 (Erica Ireland) Nist, L., & Joseph, L. (2008). Effectiveness and efficiency of flashcard drill instructional methods on urban first graders' word recognition, acquisition, maintenance, and generalization. School Psychology Review, 37(3), 294-308. Research has shown that school children are not receiving important basic reading skills. Children should be taught how to read words accurately and quickly. This may need to be taught and practiced in isolation. Teachers are under such a huge time restraint that they desire a strategy for teaching sight words with as much effectiveness and efficiency as possible. Three separate flashcard studies are: incremental rehearsal, interspersal and traditional drill and practice methods. Each flashcard method was compared to the others to measure: (a) the most effective for helping the child to read words on the following day retention probes, (b) the most efficient method, (c) most effective in helping the child maintain the words that were learned, and (d) the greatest improvement in contextual reading. The participants used in this study were four females and two male Caucasian first grade students. They all attended an urban elementary school in Ohio. These students were identified by their teacher in having a difficult time reading consonant vowel pattern words. They were each administered a pre-assessment consisting of 200 words randomly selected from the children’s literature in the classroom and a form list of high frequency words. Verbal feedback was provided for the students if they were able to correctly name the word within the three second time frame. Words correctly named on both assessments were considered known and words not correctly named on both assessments were considered unknown. These unknown words were used to create the three 36 word sets with nine words from each consonant vowel pattern. The words were from four of the consonant vowel patterns (CVC, CVCV, CVVC, and CVCC). All of the words were written on index cards. A score sheet was created that had a column for the words and a place for a “C” to be placed for correct and an “X” was placed next to the words read incorrectly. Upon administering the test with the list of words, if a child missed a word on the next day retention probes then it was considered unknown and used the following day when the new words were randomly selected until a total of 6 words was reached. The study was conducted for approximately 4 weeks. There were three sessions during each week. The retention probes were given before the second session took place and was the only thing that took place during the third session of the week. The three different flashcard methods were rotated in the order they were used each day. Each session was timed from the moment the first word was read to the last word was read by the student. The only feedback provided in the study was “good job or very good” for the correct reading of an unknown word or the correct pronunciation of the word if it was pronounced incorrectly. The three flashcard studies were conducted as follows: Traditional drill and practice: 6 unknown words were presented on flashcards. The instructor pronounced the word and asked the child to repeat it. The flashcards were presented again and the students were asked the words. The flashcards were shuffled at the end. Interpersal Training: 6 unknown and 3 known words were presented on flashcards. The 3 known words were mixed into the unknowns in this pattern KUUUKUUUK (k=known and u=unknown) The 6 unknown words were read first by the instructor. Then the student was asked to read the word orally. The six unknown words were shuffled and the known words were placed in the first, fifth and ninth presentation spots. Incremental rehearsal: The six unknown words were presented nine times among the 9 known words. The words were rotated through a very direct pattern. The pattern continued until all 6 unknown words were presented. The instructional effectiveness was measured as the number of words that they read correctly on each retention probe that was given the next day. The 18 unknown words were presented as one group of words and were shuffled and placed in random order. The instructional efficiency was measured by the number of words read correctly on the retention probe multiplied by 60 seconds. To determine if the learning of the new words was retained by the students, a maintenance probe was issued five days after the final instructional session ended. The results of the three flashcard studies showed that the students read more accurately after undergoing the incremental rehearsal condition. The research showed that 5 out of 6 students were able to read the words on the following day’s retention probe. The traditional approach allowed more words per minute to be read due to the straight forward approach to this method. The teachers of these students felt that the students benefited from this study and their word reading skills increased. The students were asked which flashcard approach they liked the best and they all agreed that they liked the traditional approach because it took the least amount of time. Student’s preference is important to factor into selecting the interventions. Although the incremental rehearsal is more time consuming it can be more intriguing to the students when they can see they already know some of the information that they are required to learn. Overall this study provided a wonderful look into different flashcard approaches that one can take when helping novice readers learn new sight words. The three approaches showed solid evidence in the amount of words that the students were able to retain. The traditional approach showed an average of 76% to 85% words maintained, the interspersing approach showed 83% to 90% words maintained and the incremental rehearsal showed 81% to 96% words maintained. This study provided a wonderful tool that is very effective and efficient to use with students to help replace the ineffective approaches that are still used in classrooms today. Article 6 (Erica Ireland) Stuart, M., Masterson, J., & Dixon, M. (2000). Spongelike acquisition of sight vocabulary in beginning readers?. Journal of Research in Reading, 23(1), 12 Development of sight vocabulary should be “spongelike”. Stuart, Masterson and Dixon wanted to put this theory to a test. Two training methods to investigate the acquisition of new sight vocabulary words were created and executed. The first method infused sight words into vividly illustrated text. The second method contrasted the use of flashcards against learning words in illustrated text and a mixed approach that combined both the use of flashcards and books. The student’s phonological awareness and sound to letter mapping skill was considered in each of the methods. In method one, the students were grouped based entirely on their phonological awareness and sound to letter mapping skills where in method two, the students were assessed but grouped heterogeneously. Method #1: The subjects were five year olds from two classrooms in an Inner City primary school. All students were screened using the Ability Scales Single Word Reading Test. Students that could read no words were screened using the Initial Sound Segmentation and Sound to Letter Matching. Based on the date collected by these two tests, the students were broke up into two groups of ten children. They were labeled GP+ for students with good graphophonic skills and GP- for students with little or no graphoponic skills. The students were taken out of the classroom in pairs. They were read the books and asked to pay attention to the words printed in red. Each child repeated the word when the trainer pointed to it. The students were then tested on 16 red flashcards. This procedure remained the same until sessions four to six where the trainer asked the students to pay attention to the some of the letters to help them to be able to remember some of the words. The “spongelike” acquisition that was supposed to take place was very low. The most words that any child was able to learn was 12 out of 16. Two of the students were unable to learn any words. The results from this first study would suggest that the students need much more exposure to the sight words that were presented to the students. It was also suggested that the students would benefit from clear instructions to try to remember the words. In this training method, the GP+ students showed better retention at post testing than the GP- students. This would give some weight to the idea that better phonological awareness and alphabet knowledge does effect sight vocabulary acquisition. Visual memory was considered a last resort for the students who had no other strategy or knowledge to help them to remember the sight word. Training Method #2 This method contrasted three separate approaches to learning sight vocabulary words. It was predicted that “ the flashcard condition would prove the most efficient both in terms of amount of learning and training time.” (Stuart, Masterson & Dixon, 2000) Students recall was tested under three conditions: (a) isolated word, (b) word-picture matching, and (c)word in sentence (Stuart, Masterson & Dixon, 2000) Three separate groups of ten children were created, a GP+, a GP- and a mixed group. The trainer of this exercise was “blind” to the makeup of the group. The materials that were used in this training method were: four rhyming question and answer books with lively illustrations. The target word appeared once on each page in red colored font. Two sets of flashcards of the target words were used, and for post-testing a set of pictures and a set of eight sentences from the books were added. All students were asked the target words and none of them could read them. Each of the sessions was timed. The measure of learning in each session was taken immediately after each session ended. Flashcard group: The students were told the word on the card and asked if they knew what it was. It was important that they knew the meaning of the word. After all eight words were given the cards were shuffled and looked at again until the children had seen them eight times. Book group: The students were instructed to look at the words while the trainer read the words from the book. They were told that the ones that they were to remember were in read. The trainer stopped when reading one of the red words, pointed it out and told the children the word and gave clarification so all students had understanding of the word. All four books were read each session so the students were exposed four times each session as well. Mixed group: They were given the same instructions as the book group but before the page was turned and they were exposed to one of the red words, a flashcard of the word was shown to them and the children were encouraged to look at it and repeat and read it. After all the data was analyzed, the flashcard group learned significantly more words than the other two groups. They were able to recall more words independently, match more pictures to words correctly and they had better reading of words in context. The time of each session was taken and analyzed. The data showed that teaching children new vocabulary by using flashcards leads higher achievement in learning the target words. It had no detriment on their comprehension or their ability to recognize the words in text. Learning new sight words is a skill that all children must and will do. There are many factors that go into that learning such as who the child is, the learning conditions that they are placed in and the words that they are asked to learn. Comparing the data across the two training methods, there was an obvious correlation between learning new words and the use of flashcards. The trainers were able to focus the children’s attention to the printed words, provide the necessary repetition for them to learn the words without any negative effects to their understanding or ability to read the words in context. Article 7 (Erica Ireland) Parette, H., Blum, C., Boeckman, N., & Watts, E. (2009). Teaching word recognition young children who are at risk using Microsoft PowerPoint coupled with direct instruction. Early Childhood Education, (36), 393-401. doi: 10.1007/s10643-008-0300-1 Emergent literacy is the reading and writing behaviors of preschool children that serve as the basis for reading and writing. The early experiences that the young children have play a significant effect on their later abilities to read and write. (Parette, Blum, Boeckman & Watts, 2009) These are the main components of emergent literacy: (1) phonemic awareness, (2) concepts of print and (3) alphabetic principle, (4) vocabulary development, and (5) comprehension. Instruction in each of these areas is often essential for learners who are at risk (Parette, Blum, Boeckman & Watts, 2009). One area of particular importance in a young child’s emergent literacy development is word recognition. Young children must have a strong foundation in this area in order to be able to be strong readers. They must develop the ability to read words automatically when they are reading text. Building the base of words that are automatically recognized, “serves as a critical basis for skillful reading and writing” (Parette, Blum, Boeckman & Watts, 2009). The students that fail to develop automaticity are at risk of becoming struggling readers. A teacher should be able to see his/her students developing an increase of vocabulary words that is used not only in reading but threaded throughout the entire school day. Vocabulary can be introduced prior to reading a text but it can also be indirectly taught by exposing students to words and giving them their own opportunities to read. Direct Instruction is a research based approach to reaching at risk students. It consists of carefully structured lesson plans. These plans can be taught whole group or small group. Instruction is referred to as “active teaching” that is characterized by (a) full-class or small group instruction, (b) organization of learning around questions posed by the education professional, (c) provision of detailed and redundant practice, (d) sequential presentation of material to facilitate mastery learning of each new fact, rule or sequence before the presentation of subsequent ones, and (e) formal arrangement of the classroom to maximize recitation and practice (Parette, Blum, Boeckman & Watts, 2009). It is extremely important when using this approach that the young students are given multiple opportunities to practice the strategies that are being taught to them and when appropriate the time to apply them. It is considered a very powerful strategy to help facilitate reading instruction in preschool classrooms. Direct Instruction has shown positive effects on both typical and at risk students. It allows them to acquire higher order thinking skills, and they are able to apply what they have learned in new situations. Direct Instruction has been used to teach (a) phonological awareness, (b) word recognition, and (c) comprehension (Parette, Blum, Boeckman & Watts, 2009). An increase in the value of the use of technology in the classroom has become an important piece of the educational puzzle. When used appropriately, computers and software can become valuable tools that increase the students learning. This has not always been the case. In 1996, using technology in classrooms was very controversial. The National Education of Young Children felt that it was developmentally inappropriate for classroom settings. In the 12 years since the writing of this article much has changed. The availability and students use of technology has increased tremendously. Microsoft PowerPoint is a very familiar technology program that allows the student to see and interact with the material that is being presented. Students are easily engaged and interested in what is coming up on the screen. Research has been conducted with the use of PowerPoint and Direct Instruction to help teach phonological awareness skills to preschool students who are at risk. The “Ready –to-go” PowerPoint templates addressed alliteration, rhyming, and initial sound fluency. The clipart on the slides was considered age appropriate, monosyllabic names of common objects, animation, sound, layout design that compliments Direct Instruction and instructional scripts (Parette, Blum, Boeckman & Watts, 2009). The PowerPoint intervention was given for 10 minutes, three times a week. There were two groups of students: the comparison group and the treatment group. Both groups used the PowerPoint presentations but the comparison group did not use Direct Instruction. They only used a standard curriculum. Both the comparison and treatment group showed a significant gain in abilities in rhyming, alliteration, and initial sound fluency. The largest gains in learning were seen in the treatment group in initial sound fluency. This was measured based by using DIBELS. This group was able to double their progress over the comparison group. Pairing Direct Instruction and PowerPoint can be a powerful tool to help with the instruction of word recognition. The two challenges that face young learners are phonemic understanding and orthography. “Direct Instruction makes instruction explicit and systematic. “ It allows young children to become attentive to the orthographic and phonemic nature of word recognition” (Parette, Blum, Boeckman & Watts, 2009). A teacher should only choose a few words that are directly linked to the curriculum or lessons that are being taught for the day. When considering words to use in the PowerPoint, a teacher should try to choose words that are unknown and known. Beginning with words that are related to one another in word families is a great place to start. A teacher should carefully choose graphics that are known and easily recognizable. This will help the students to make connections to the new words being presented in the PowerPoint. Creating a script to use while introducing the new words to the students will also help to support word recognition. The students will be able to apply the sounds of the text to the orthography of the text. When presenting new words in PowerPoints to the students, it is important to show the word and visual cue multiple times. By exposing the students to the new words multiple times the students will have opportunities to see the word and picture and make the connection. The teacher will also be able to provide positive praise for correct responses and guided correction for responses that are incorrect. This approach of using Direct Instruction and PowerPoint demonstrates showing the word and corresponding picture nine times. Each slide represents the word in either picture and word or word format. It is highly recommended that if using a word such as “cat” the teacher should introduce the remaining words in the short a word family in the remaining slides. This will allow the students to begin to see the relationship between the words along with noting the differences. This would be a valuable to teach the short vowel word families. After presenting the slides to the students, an assessment should be given to the students. The slides can possess the words without pictures to see if the students are able to read the new words that were taught. They can be presented in word families to help support the student’s word recognition. A low tech approach to word recognition assessment can be given to the students as well. The students can be given a response card that provides word choices for the students to use. This will help the teacher to see which student has mastered the words that have been taught along with the students that are struggling. Another step a teacher could use within the PowerPoint is to provide animation with the graphic that was used to represent the word that is being taught. The movement that they graphic is associated with will provide another format of positive feedback. If the student is able to read the word correctly, the graphic will move. In conclusion, young children are familiar and prefer lessons that incorporate technology. It is important for teachers to provide opportunities for students to use technology along with teaching lessons that incorporate it into the learning. Microsoft PowerPoint is a program that is readily available in most classrooms and it is easy to use. It provides the repetition that helps students to master new words and allows the incorporation of pictures to allow students to help make real connections. Teachers should embrace technology and use it to help improve and support their student’s education. Article 8 (Erica Ireland) Johnston, F. R. (2000). Word Learning In Predictable Text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92, 248-255 The use of predictable text in classrooms is a popular approach to teaching students how to read and increase sight word knowledge. The purpose of this study is to test whether beginning reader’s word learning is enhanced with the use of predictable text in three components of a whole to part instructional model. Predictable literature is replacing the traditional basal reader. Advocates of the use predictable text believe that it “enables beginners to feel successful in their earliest attempts to read”. (Johnston 2000) Three approaches to teaching beginning reading and word learning were studied: (1) Repeated readings: This method is well established among practitioners. Text is read and reread to strengthen word recognition, speed, expression, and comprehension. It is very helpful in increasing fluency. (2) Whole to part activities: The text is read as a whole group, then the students work with samples of the text that has been written on sentence strips and word cards. The teacher draws the student’s attention to words, letters and sounds. This does seem to help facilitate the learning of new words as the student’s attention is drawn to the words. (3)Word banks: This is a personal collection of self-selected known words. These words are removed completely from the text which forces the students to use the “graphophonic information” provided by the letters. In earlier studies that examined sight word acquisition in context versus isolation, the evidenced supported the notion of learning words in isolation, where all contextual clues have been removed; students showed considerable growth. The hypothesis that is being tested is, “the best word learning would take place under conditions in which contextual support was minimized and a greater degree of attention to details of the print was required to carry out the task”. The basis of the student’s literacy achievement was also taken into account during this study. The participants of this study were first grade students from a small city in the Middle Atlantic States. The three teachers that were used in this study varied on work experience but had the same reputation within the school as excellent teachers. Prior to the study, the students were individually administered the ERSI and the Wide Range Achievement Test word lists to determine that none of the students were “beyond the beginning reading stage” and to form the three post hoc groups to examine the interaction of the treatments with level of reading achievement” (Johnston 2000). Same ERSI scores showed that there “were no significant differences between the classes in terms of literacy skills prior to the study” (Johnston 2000). The student’s scores from the ERSI were used to rank the students from highest to lowest. Students scoring 27 or higher were in the high group, 17 to 27 were in the middle group and below 17 were in the low reading group. There were 9 comparison groups all together across three first grade classrooms. These groups were also used to address the question of whether students “profited differentially from the treatments on the basis of the level of their print-related skills” (Johnston 2000). There were nine predictable books used in this study. They were selected from the Story Box in the Classroom: Stage 1. Three books were used each week with all of the students. The books were fairly equivalent in the number of different words presented. Any words that were presented more than once in the books were dropped from the data analysis. The students were exposed to 41 to 66 unique words each week with a total of 160 words across three weeks. Each book was introduced to all three groups in the shared reading approach on day 1 of the 4 day plan. The teacher led a brief discussion of the title and cover. The book was read to the group as a whole and then the students were asked to read and follow along in their own copies two times. The students were encouraged to point to words as they read. Immediate feedback was given to the students if a word was named incorrectly. On subsequent days 2-4, the teacher used the same book but in different contexts dependent upon which treatment approach they were working in. 1. Repeated readings: The story was read 10 times over a four day period in its original context. The students did take part in dramatic interpretations of the text while other students read the text aloud. 2. Sentence context treatment: After reading the book chorally on day 2, the students read the text on a chart minus the support of illustrations. They then worked together to rebuild the story using sentence strips. Days 3 and 4, the students read the text independently and worked on rebuilding the story using individual sentence strips. 3. Word Bank Study: On days 2 and 3, the students read the story in context and were then given papers of the text minus the illustrations. The students were told to underline the words that they could identify. These words were placed on index cards and placed in the student’s personal collection. Day 4 the students read the story again in full context and then reviewed their word collection. These words were collected at the end of the week. Each week the students were pretested with a random list of words they would see in the predictable text, and post tested with the words they were exposed to over the week. The students were assessed again in three weeks to check for word retention. Known words on the pretest were subtracted from the immediate and delayed recall tests. This left only newly acquired words for analysis. The first analysis in this study looked to see if there was an impact in word learning based on the treatment and teacher or the treatment and book. There were no significant findings. The most significant gains in this study were shown in both the immediate and delayed recall posttests. The findings supported the originally stated hypothesis, that the most word learning would take place in the word bank group. The next highest scores were in the sentence context and lastly the repeated reading, which showed the smallest amount of new words acquired. In regards to time of recall by achievement interaction, there were significant differences between all three groups. Most obvious was that the high achievers outperformed the average that in turn out performed the lowest achievers. In further examination of the word bank treatment, the highest achievers were able to learn five times more words across all three conditions than the lowest achieving group and twice as many words as the middle group. The major purpose of this study was to examine whether beginning readers who use predictable text are able to learn more words when it is enhanced with levels of support in a whole to part approach. Rereading needed to only pay a small amount of attention to the printed forms of words. All of the non- print clues had more of a negative effect on the student’s ability to learn new words. There was also no pressure to pay attention to the words on the page due to the memorization of the text. Sentence Context provided more of an opportunity for the students to focus on print when they were working with the sentence strips. This may have been the reason that these students were more able to learn more words. In the word bank group more words were learned when the words were removed from the context and illustrations. This forced the students to focus on the graphophonic cues. “Where context is strong enough to allow quick and confident identification of the unfamiliar word, there is little incentive to pore over its spelling. And without studying the word’s spelling, there is no opportunity for increasing its visual familiarity” (Johnston 2000). (This statement here was a real light bulb moment for me) Learning new words can be thought of as the retention of stimuli. The more it is focused on and processed, the more it is retained in the brain. Each of these treatments requires the students to use different levels of processing. Predictable text does help students begin to develop sight vocabulary due to the repeated exposure from reading. More words can be learned if the child is allowed to focus on the word in a more one on one approach with the use of flashcards. Another factor that may have played into the level of word learned is the varying degree of literacy or alphabet knowledge and phonological awareness. There are advantages for using predictable reading material. They provide support to the young reader by using text that is easily remembered. Predictable text will only help support beginning readers and struggling readers. It will not help students with words that are not easily decodable or frequent. Teachers need to work hard on maintaining a balance between contextual support and attention to print. There are still questions about whether predictable text is helpful or hurtful. Many more studies will need to be done to decide this factor. It should be used as a tool to teach one of the many components of reading too young or struggling reader. In conclusion, I have learned that flash cards can make a poor reader a better reader when used properly. Excessive drilling in long sessions will turn students off to reading altogether. The use of technology with flashcards is something I have never done. I plan to implement this technique into my classroom to help the students. Allowing students to understand each word and then having them see these words in text will greatly contribute to permanent improvements in children’s reading skills. Good readers need to be able to identify high-frequency and irregularly spelled words in order to successfully read stories. A child’s rate and comprehension are likely to be lost if they are spending too much cognitive energy struggling with each word. I am confident from all the articles I have read that by using the proper techniques, flashcards can promote fluency, help children recognize sight words with automaticity and greatly increase their sight word bank. References Johnston, F. R. (2000). Word learning in predictable text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92, 248-255 Mechling, Linda, David Gast, and Kristin Krupa. "Impact of SMART Board Technology: An Investigation of Sight Word Reading and Observational Learning." Springer Science Business Media. 9 March 2007: 1869-1882. Print. Murray, O., & Olcese, N. (2011). Teaching and learning with iPads, ready or not?. TechTrends, 55(6), 42-48. (This article was used as a reference in the PowerPoint presentation) Nicholson Tom. (1998). The flashcard strikes back. The Reading Teacher, 52 (2), 188-192. Nist, L., & Joseph, L. (2008). Effectiveness and efficiency of flashcard drill instructional methods on urban first graders' word recognition, acquisition, maintenance, and generalization. School Psychology Review, 37(3), 294-308. Parette, H., Blum, C., Boeckman, N., & Watts, E. (2009). Teaching word recognition young children who are at risk using Microsoft PowerPoint coupled with direct instruction. Early Childhood Education, (36), 393-401. doi: 10.1007/s10643-008-0300-1 Stuart, M., Masterson, J., & Dixon, M. (2000). Spongelike acquisition of sight vocabulary in beginning readers?. Journal of Research in Reading, 23(1), 12 Tan, Annette, and Tom Nicholson. "Flashcards Revisited: Training Poor Readers to Read Words Faster Improves Their Comprehension of Text." Journal of Educational Psychology. 89.2 (1997): 276-288. Torgesen, Joseph, Mary Water, Andrew Cohen, and Jeffery Torgesen. "Improving Sight-Word Recognition Skills in LD Children: An Evaluation of Three Computer Program Variations." Council for Learning Disabilities. 11.2 (1988): 125-132. Print.