The Lending Interest Rates in the Microfinance

advertisement

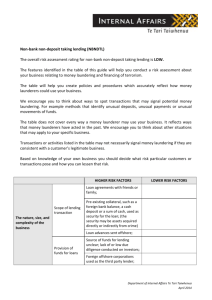

The Lending Interest Rates in the Microfinance Sector: searching for its determinants Abstract Using data of 1,299 microfinance institutions in 84 countries and following different approaches, we find that the lending interest rate is determined by the funding cost, the loan size and the efficiency level of microfinance institutions. Regarding competition, results are mixed. Is only in Asia where a negative correlation between competition and lending interest rates can be detected. For other subsamples, we find that competition is more likely to be negatively correlated with the size of loans. Pablo Cotler Universidad Iberoamericana, Mexico DF pablo.cotler@uia.mx JEL: G21, G28 Keywords: Africa, Latin America, Asia, lending interest rates, microfinance 0 I. Introduction The correlation and causality among economic growth and financial development has been thoroughly analyzed at the macroeconomic level (Levine, 2005). Further, studies such as Beck, Demirguc-Kunt and Levine (2007) reveal the importance of greater financial leverage: it affects in a disproportional manner the income of the poorest 20% of the population. Thus, the development of financial institutions not only helps to reduce poverty, it may also help to scale down inequality. According to Beck, Demirguc-Kunt and Martinez Peria (2007), roughly 40 to 80 percent of the populations in most developing countries lack access to formal sector banking services. Thereby, the increased surge of microfinance institutions across less developed countries should help cash starve entrepreneurs to unleash their productivity and raise their income above poverty lines. However, measurable results of their impact are not easy to find. Papers by Pitt and Khandker (1998), Morduch (1998), Banerjee and Duflo (2004), Alexander-Tedeschi and Karlan (2006) and Hermes and Lensink (2010) show –among others- that there are several methodological difficulties to correctly assess the impact of access to financial products. As a result, the debate concerning the impact of microfinance on poverty reduction is far from settled. Certainly this is puzzling given the steady growth of micro lending institutions across the developing world. Loans offered by microfinance institutions are not necessarily new to the population they serve. Small entrepreneurs and poor families have typically being in contact with informal lenders that offer short-term small-loans and make use of social and market sanctions to avoid borrowers from defaulting (Aleem, 1990)1. If informal lenders exist, microfinance institutions may have a positive impact on businesses profitability and on household wealth if they charge an 1 interest rate that is well below the cost of informal loans and/or if the loan size been offered is sufficiently big to solve indivisibility problems. But how high are interest rates in the microfinance industry? According to the Microfinance Information Exchange database2, the annual nominal lending interest rate charged by microfinance institutions during the period 20002008 was on average 42% in Africa and in Latin America and 35% in Asia. Since the annual inflation rate was approximately 7% per year in all three continents, real interest rates were high. Even though there is no worldwide cross section-time series data on interest rates charged by individual moneylenders, rates charged by microfinance institutions are perceived –according to conventional wisdom- to be well below those charged by neighborhood loan sharks. Notwithstanding such perception, there is plenty of dissatisfaction among microfinance practitioners regarding the high interest rates most microfinance institutions charge (see for example, Rosenberg et al., 2009, Gonzalez, 2010 and the worldwide reactions following the initial public offering of Banco Compartamos in 2007). Since interest rates affect the probability that financing spurs growth, it would be useful to know what factors cause these high interest rates. Do they closely follow the interest rates that financial institutions pay for their funding? Or are the operating costs the main cause? Or perhaps, these high interest rates are the result of a lack of competition in the credit markets. To answer such questions, we used the information collected by the Microfinance Information Exchange. This dataset includes information on financial income, the value of the loan portfolio, average loan size, cost of funds, lending interest rates, operating costs, delinquency rates, number of clients, profitability, etc., for 1,299 financial institutions located in 84 countries throughout Africa, Asia and Latin America for the period 2000 to 2008. As happens with any non- mandatory database, self selection may bias our results. However, given the visibility of this 2 webpage (300,000 visits per month) and the funding opportunities it provides, it is very likely that the most important microfinance institutions of all 84 countries are included in this database. To fulfill our objective, we followed two approaches. Following Cull, Demirguc-Kunt and Morduch 2006, we first examine the determinants of the lending interest rate by regressing such variable against the cost of funds, the operational cost, the average loan size, the rate of profitability, a proxy for competition, the type of financial institution (bank, cooperative, etc.) that is offering such micro loans, and a set of dummies to control for time waves and geographic location. This approach, however, may be misleading if managers of these institutions have a profitability goal –regardless of whether it is distributed among owners- which enables them –for example- to increase the loan portfolio and/or the number of borrowers, expand the number of branches and/or the number of loan officers or simply to be financially self-sufficient. Whatever their objective, a profitability target and the characteristics of their market niche are essential when deciding an appropriate pricing policy and a loan size within the time-scale that they are willing to offer. Taking this description into account, a second approach consisted on estimating a system of equations that is simultaneously solved. Regardless of the approach followed, three results stand out for their policy implication. First a reduction in the funding cost leads to lower lending interest rates. However, 90% of all microfinance institutions of our sample had an average cost of capital of 0% in real terms; thus, there is not much room for further reductions. Second an increase in efficiency leads to lower lending interest rates, being its impact increasing with the initial size of microfinance institutions. Third, it appears that competition is more likely to have an impact on the loan size than on the lending interest rate. To show these results, the paper was divided into four additional sections. In the first one 3 we provide a literature review. The second one describes the database we consulted and the methodology we used. Then in the third section, we present and discuss our findings. Finally in the last section we conclude. II. Literature Review When analyzing lending interest rates charged to small entrepreneurs, the first issue that comes into mind is whether they follow a pattern that is consistent with how much competition financial institutions encounter in such markets. While the structure-conduct-performance theory suggests that greater competition among lending institutions should bring interest rates down, the informational problems that surround credit market transactions may weaken such argument. Furthermore, some authors predict the existence of a negative correlation between market power and interest rates. For example, Peterson and Rajan (1995) found that lending institutions that wield greater market power are those with enough resources to invest in relationship lending. Thus, as market power increases, the likelihood that smaller firms will be granted loans is greater and therefore interest rates should decline. With a different argument, Marquez (2002) and McIntosh and Wydick (2005) arrive to the same conclusion: as competition among financial institutions increase, default risks may follow a similar path and so do interest rates. However, other authors have an opposite view. For example, Boot and Thakor (2000) claim that a relationship orientation helps to partially protect the financial institution from competition. Thereby, higher competition may induce financial firms to reallocate resources towards more relationship lending and therefore smaller firms may face a reduction in the lending interest rates. Thus, two conflicting hypotheses may be found regarding the effects that an increased competition in credit markets for small firms has on the lending interest rate. 4 But the structure-conduct-performance framework may be misleading if market contestability is a relevant feature of credit markets for small firms. However if potential borrowers lack formal documentation to certify their income and expenditure flow, it is very likely that financial institutions may need to develop special techniques to assess the risk profile of these potential borrowers. In this scenario, an entrance threat is not necessarily sustainable and could therefore call into question the issue of market contestability and its effects on interest rates. Taking into account all these factors, the interaction between competition and the lending interest rate charged to small entrepreneurs may be ambiguous. Whether the correlation between market structure and interest rate is positive, negative or null, it is a question to be solved empirically. However, a review of the literature also shows conflicting results. On the one hand the results found by Boot and Thakor (2000) and Ongena and Smith (2001), support the traditional structure-conduct-performance hypothesis. On the other hand, the findings of Petersen and Rajan (1995) and Zarutskie (2003) support the alternative hypothesis. Furthermore, the results depend on the methodology and on the characteristics of the database. For example, Carbó, Rodríguez and Udell (2006) show that the sign of the correlation is sensitive to how market power is assessed. If market power is defined by the Lerner index, their results support the conventional theory: greater market power implies higher interest rates. However, if market power is defined by concentration indexes, their results are the opposite and the conventional theory is discarded. But interest rates are not only determined by real or potential competition; the characteristics of borrowers and lenders also matter. For the microfinance sector, Rosemberg, Gonzalez and Narain (2009) and Gonzalez (2010), suggest that tiny loans with very low default rates require high administrative expenses that may not be offset by economies of scale. Further, 5 even though microfinance institutions have -on average- a higher profitability rate than commercial banks, these same authors claim that the search for returns is not an important driver of interest rates. While such hypotheses may be appealing, these authors do not explain how they arrived to such conclusions: there is no information regarding the econometric method being used nor what other explanatory variables were considered nor any information regarding the statistical significance of their results. Cull, Demirguc-Kunt and Morduch (2006) examine the determinants of profitability, portfolio at risk and loan size in the microfinance sector without taking into account how much competition lenders face because the typical proxies for such variable have endogeneity problems and do not measure how intensive is competition. Using the Microfinance Information Exchange database for the period 1999-2002, they find –among other results- that the lending interest rates and the capital costs affect the profitability of financial institutions. Their conclusions however may need to be re-examined since they are obtained through the use of least squares estimations in which it is implicitly assumed that the estimated coefficients are independent of the size of the institutions and that there is no simultaneity on the decisions taken by managers of microfinance institutions regarding interest rates, loan size and profitability. III. Data and Methodology Obtaining financial information of those institutions involved in microfinance is not easy because in most countries there is no financial authority that supervises the recollection of such data. Furthermore, the absence of organized market supervision means that these entities could freely decide how to measure the variables describing their different sources of income and expenditure. Finally, even if there were an informal consensus on how to measure these 6 variables, that would not necessarily ensure that the information is reliable since it is very likely that accounting deficiencies might exist. To solve these problems we used the information collected by the Microfinance Information Exchange (Mix). Members of this network report their financial results to managers of this organization which in turn make sure that the definition and methodology used to define each variable is unique across institutions. Thanks to this, we have annual information for the period 2000 to 20083 concerning financial income, the value of the loan portfolio, average loan size, cost of funds, lending interest rates, operating costs, delinquency rates, the loan loss provision rate, number of clients, profitability, etc., for 1,299 financial institutions located in 84 countries throughout Africa, Asia and Latin America (see table 1). Given the time span considered and the number of years that these institutions have been reporting their data to the Mix, we have an unbalanced cross section-time series panel data of 4,718 observations. INSERT Table 1 Even though the database could have a self-selection bias, it is worth using it for several reasons. First of all, it is a conceptually homogeneous database: each variable has the same meaning for each institution. Second, very few micro-finance institutions are willing to share their inter-temporal experiences, so having such a panel of data may help understand the dynamics of lending interest rates. Finally, even if the panel of data is not representative of all microfinance institutions, collectively however is very likely that they serve a very large fraction of microfinance customers worldwide. Thus, we consider that this work may be an important 7 step in the empirical literature on the management of microfinance institutions in developing countries. As is usually done, the lending interest rate is measured as the portfolio yield: all interest and fee revenue from loans divided by the average gross loan portfolio. Thus, is a weighted average of the interest rate actually received by the financial institution. Using such definition, Table 2 shows that the median interest rate charged in Asia is lower –relative to what is being charged in America and Africa. Notwithstanding such result, microfinance entities in Asia earn a similar rate of return. Surely default rates, operating and funding costs as well as the size of financial firms may help explain such outcome. INSERT Tables 2 and 3 Following Martinez and Mody (2003) three sets of variables might explain the pattern followed by the lending interest rate. First we have the capital cost and the operational cost per peso lent of the financial entities. If the latter is turned upside down, we could use it as a proxy of how efficient these entities are4. However the “quality of the product” needs to be considered. To explain this better consider two examples. First, imagine two financial entities that report the same average operational cost but have different default rates. In this scenario, the institution with the lowest non-payment rate should be considered more efficient. Bearing this in mind, efficiency may be better measured by adjusting the average operational cost by the portfolios’ default rate. Now let us consider two financial entities whose average operational cost and default rates are similar, but report different average loan size. Taking into consideration that smaller loans carry out higher operational costs, the entity with the smaller loan size should be 8 considered more efficient. For these reasons, a better proxy for efficiency will be achieved if the operational cost per peso lent is adjusted by the portfolio default rate and by the relative size of loans granted by the institution1. The second set of variables includes those describing the size and nature of the financial institutions, the earnings they make and the number of years they have been operating. As an indicator of the financial firms’ size we used the value of their financial assets and loan portfolio, both measured in real terms and expressed in logarithms. Regarding the nature of these financial entities, six dummies were considered, each one representing the following type of institution: non-bank financial institution, non-government organization, rural banks, credit union or cooperative, banks, and any other type. Further, the average loan size, the loan loss provision rate and a proxy for their market niche were also included. For the latter, denoted as outreach, we used the average loan size divided by gross domestic product per capita. As explained before, it is difficult to measure how much competition financial entities face. Further, given the characteristics of our dataset we would need to have a cross section-time series panel data set for such variable. Since the vast majority of the institutions that comprise our sample do not operate at the national level and usually compete with informal moneylenders, the information required to construct such a variable would be tremendous and to our knowledge such dataset does not exist. Notwithstanding these problems, we followed the traditional approach (see for example Kai, 2009) and considered the fraction of the adult population who are borrowers of microfinance institutions as a proxy for competition. Finally, to describe the 1 Denoting efficiency as effic, operational cost per peso lent as (cop), default rate as (def), and the relative size of loans of institution i in country j as (Lij)/(Lj), it follows that the efficiency of institution i in country j equals: (1/cop)(1-def)( (Lj)/(Lij). 9 economic environment we included a legal rights index and a credit information index, variables that are available in the World Bank dataset Doing Business. INSERT Table 4 With the use of this data, first we followed the standard approach and examined the determinants of the lending interest with the use of one equation. In this scenario our hypothesis may be described by the following functional relationship: Iloan = F(Ifund, effic, roa, avgloan, competition), whereas: I1>0, I2<0, I3>0, I4<0, I5<0 ….(1) Where Iloan describes the lending rate of interest, Ifund measures how much they pay for their funds, effic is the efficiency of the institution to deliver its loans, roa is the return on assets and avgloan is the average loan size. Next to this functional form we describe the sign of the partial derivative we expect to find. Thus for example, we expect to find a positive correlation between the lending interest rate (Iloan) and the cost of funds (Ifund), being such hypothesis denoted by: I1>0. Further, we posit a negative correlation between the lending rate and our proxy for efficiency because as financial firms become more efficient they may be able to reduce their lending rate and still reach the same profit rate. However, if these financial firms wish to increase profits they will surely increase their lending rate, thus, I3>0. Regarding the average loan size, two possible explanations may be provided to explain why we posit a negative correlation. First, if financial firms wish to finance their variable costs, then a bigger loan size could be correlated with smaller interest rates. On the other hand, if bigger loans were received by more experienced borrowers, then credit risk would decline and so could interest rates: I4<0. 10 Regarding competition, we follow the standard theory and assume that it has a negative correlation with the dependent variable. Further some control variables were included. Among them, we have dummies capturing the different organizational structure of the financial entities and other dummies that consider differences across countries and years. However, many of the variables that could explain the behavior followed by the lending interest rate are endogenous. In particular, the profitability rate and the size of loans are two variables which the financial institution seeks to influence. Thus, managers of these organizations may have a profitability goal that allows them –for example- to enlarge the portfolio and/or increase the number of borrowers and/or create more branches and/or recruit more loan officers, etc. The profit target and the characteristics of the market niche, results in an optimal pricing policy comprising a loan size within a time-scale. Accordingly we believe that the loan transaction may be described in three steps. First, the financial firm decides how much to charge and what the optimal loan size must be in order to reach its profitability goal. Once known the value of the lending interest rate and the average loan size the financial institution offers, a potential customer decides whether s/he wants to request a loan. Taking into account the credit history of the potential borrower and its income-expenditure stream, the financial institution builds a risk profile of the individual. With this at hand, they decide where to lend or not. While for first time customers the typical microfinance institution does not allow any kind of negotiation related to the loan size, for repeated customers some sort of negotiation is possible but is the financial institution that –taking into account its goals- decides the loan size. Taking this description into account it could be more reasonable to estimate simultaneously the following three equations: 11 2a. Iloan = F(Ifund , effic, roa, avgloan, competition…); I1>0, I2<0, I3>0, I4<0, I5<0. 2b. Roa = G(Iloan , Ifund, effic, reserves, outreach, …); roa1>0, roa2<0, roa3>0, roa4 <0 and roa5 with an ambiguous sign. 2c. Avgloan = H(effic, age, competition, Iloan …) ; Avgloan1<0, Avgloan2>0, Avgloan3 <0 and Avgloan4 <0. In this system, equation (2a) is similar to equation (1). With regard to the profitability rate, equation (2b) suggests that it will be explained by the lending interest rate, the cost of funds, the efficiency of microfinance institutions, their loan loss ratio and its market niche. As shown by equation (2b), profitability will raise when the lending interest rates and/or efficiency increases or when the cost of funds declines. Since holding loan loss reserves imply an expected loss and an opportunity foregone, we expect a negative correlation between this variable and the profitability rate. Finally, with regard to outreach, the correlation could go either way. Assuming poorer people receive smaller loans, we could expect a positive correlation between outreach and the profitability ratio (roa) because the incentives to default among this population are smaller since they want to avoid informal moneylenders. However, if smaller loans imply higher average operational costs, then outreach could be negatively correlated with the profitability rate. Finally equation (2c) describes the behavior followed by the average loan size. As microfinance institutions become more efficient, they could offer smaller loans: Avgloan 1<0. Regarding age (that works as a proxy for experience of the financial institution), it may affect both the supply and the demand for bigger loans. On the one hand, when microfinance institutions start operations they usually offer loans of small amounts because they do not have much capital or experience and debtors tend to be people without credit history. However, if the supply of loans 12 has dynamic incentives (i.e., the services offered by the institution increases as the debtor builds his credit history), is very likely that the loan size will increase through time. On the other hand, if loans have a positive impact on wealth, is possible to assume that the demand for bigger loans will rise. Under these assumptions, we expect to find a positive correlation between the average loan size and age (Avgloan2>0). Regarding competition we follow the credit card interest rate literature and assume that competition leads microfinance institutions to search for new markets. However the sign of the correlation could be ambiguous since it depends on whether they start lending to relatively non-poor people (Avgloan3>0) or moving to poorer neighborhoods and offer smaller loans (Avgloan3<0). Given their technology and stated mission, we will assume that the latter effect is more likely to dominate. Finally, if a higher lending rate is being charged we could expect a smaller loan size being demanded (Avgloan4<0). IV. Results 1. Individual Estimates Our first approach consists on estimating equation (1). As Table 5 shows, the lending interest rate (Iloan) follows a behavior in all three continents that is consistent with our hypothesis: the dependent variable responds positively to changes in the cost of funds (Ifund) and to the return of assets (roa), and negatively to the proxy for efficiency (effic)5 and to the average loan size (AvgLoan). With regard to competition, we find that it only has an impact in Asian markets. Insert Table 5 13 Given the heterogeneity in the size of the financial institutions that comprise our sample, next we analyzed whether the parameters reported in Table 5 are sensitive to the initial size of these financial institutions6. Since a learning curve regarding the appropriate use of techniques to mitigate information asymmetries may exist, age could also be a factor that may lead to heterogeneous impacts. For this purpose we added -to the set of explanatory variables used in Table 5- new variables that are created by multiplying such set by the initial value of each institution’s asset. As results in Table 6 show, the impact of each independent variable over the lending rate will vary according to the initial size of microfinance institutions and its age. Notwithstanding such heterogeneity, on average, the sign of the estimated parameters of all independent variables are consistent with our hypothesis stated in equation (2a): the cost of funds, efficiency, the quest for profits and the average loan size help explain the behavior followed by the lending interest rate. Furthermore, once interactions are considered, we find –for the overall sample- that the impact of efficiency on the lending interest rates is higher the bigger the initial size of microfinance institutions. Insert Table 6 2. Simultaneous Estimates However, results reported in Tables 5 and 6 may be misleading if reality is better described by a system of equations in which interest rates, loan size and profitability are jointly determined. From informal interviews we learned that managers of microfinance institutions 14 have a profitability goal which enables them to increase the loan portfolio and/or the number of borrowers and/or expand the number of branches and/or the number of loan officers, etc. Whatever their objective, profitability and characteristics of their market niche are essential for them to adopt an appropriate pricing policy and a loan size within the time-scale. Thus we believe that the loan transaction may be described in several steps. First, the financial firm decides how much to charge and what should be the optimal loan size in order to reach its profitability goal. Once known the value of the lending interest rate and the average loan size the financial institution offers, a potential customer decides whether s/he wants to request a loan. Taking into account the credit history of the potential borrower and its incomeexpenditure stream, the financial institution builds a risk profile of the individual. With this at hand, they decide where to lend or not. While for first time customers the typical microfinance institution does not allow any kind of negotiation related to the loan size, for repeated customers some sort of negotiation is possible but is the financial institution who –taking into account its goals- decide the loan size. So, the financial institution sets the price and negotiates the size of the loan within a range so that it may achieve the profitability goal drawn at the beginning. To consider such approach, we estimated a system of three equations that are simultaneously solved. For such purpose we used a simultaneous equation estimation (three stage least squares regression) that considers the existence of three endogenous variables (the lending interest rate, the average size of loans and the profitability on assets) that are jointly estimated. As explained before, our joint hypothesis may be described by the following set: 2a. Iloan = F(Ifund , effic, roa, avgloan, competition….) where: I1>0, I2<0, I3>0, I4<0, I5<0. 15 2b. roa = G(Iloan , Ifund, effic, provisions, outreach,…) where roa1>0, roa2<0, roa3>0; roa4<0 and roa5 with an ambiguous sign. 2c. Avgloan = H(effic, age, competition, Iloan …) where Avgloan1>0, Avgloan2>0, Avgloan3 <0 and Avgloan4 <0. Insert Table 7 As Table 7 show, once interest rates, loan size and profitability are assumed to be jointly determined only two of the parameters of equation (2a) have the expected sign across all subsamples and are consistent with our prior and with results reported in table 5. Thus, a positive correlation with the cost of funds and a negative correlation with efficiency are found regardless of the subsample considered. Further, similar to the results reported in Table 5, we only detect a correlation between competition and the lending interest rate for Asian markets, being such correlation negative as conventional theory would suggest. In all other markets, we could not find any correlation from a statistically point of view. With regard to the other two dependent variables -return on assets and average loan sizeour results are consistent with the priors stated on equations (2b) and (2c). Three results are worth mentioning. First, taking as granted that microfinance institutions were truly trying to reach poorer people, we were expecting to find a negative correlation between efficiency and average loan size. However, with the exception of Asian markets where no correlation is found, we find the opposite: an increase in efficiency leads to higher average loan size. Since we also find that greater efficiency leads to lower lending rates, it is possible that a higher efficiency may be the result of having a more appropriate lending technology that enables microfinance 16 institutions to pick better customers. In so doing, they are able to offer lower lending rates, higher loan sizes and as a result of their improved technology, a greater profitability. Thus, such correlation does not imply necessarily a mission drift. Second, as explained before the correlation between profitability and outreach (average loan size divided by gross domestic product per capita) could have had a positive or negative sign. Assuming smaller loans go to poorer people, a negative correlation may be expected if default rates among this population are smaller. However, if smaller loans imply higher average operational costs, then outreach could be positively correlated with the profitability rate. Our results suggest that the latter argument only holds for the African subsample. Third, competition could have an impact on the lending interest rate and on the loan size. However, our results suggest that it is only in Asian markets where we can detect a negative impact in both variables. For other markets, results are mixed: in Latin America, competition only has an effect on the loan size and in Africa it has no effect -from a statistically point of view. Following our results of tables 5 to 7, a reduction in the funding cost could help reduce the lending interest rate that microfinance institutions charged. However, 90% of all microfinance institutions of our sample had an average cost of capital of 0% in real terms; thus, there is not much room for further reductions. Regarding competition, economic theory suggests that a stronger competition in credit markets could help reduce the lending interest rate. However, in markets where reputation and loyalty matters, it may well happen that an increase in competition, leads in the short run to changes in the loan size but not in interest rates. Our results suggest that: an increase in competition leads to a reduction in the lending interest rate in Asia and a reduction in the average loan size in Latin America. Finally, with respect to efficiency, all our results suggest that an increase in such variable 17 would lead to lower lending interest rates and a higher profitability. However, how exactly does efficiency increase? Technology use, management quality and hard work surely matters. However, not only are these dimensions difficult to measure but also they are not exogenous since they may well depend –among other things- on how much capital are financial firms willing to invest. Taking into account the distinctive features of microfinance lending technologies, efficiency however is not only the result of a better technology or management quality; geographical characteristics of markets in which microfinance institutions work may also have an effect on the operational costs of these institutions and thereby on how efficient they are. To include some characteristics of the environment that may shape the value of the financial firms’ efficiency, a biodiversity index7 -that captures the variability of a country’s territory in terms of height and climate- could be considered. A higher value of this index may signal a greater geographical heterogeneity and may imply that –on average- is more costly to reach customers. Further, if economies of scale in lending were to exist, population density may also have an effect on the operational costs of microfinance institutions. In this regard, data at the national level may help explain why –as figure 1 suggests- Asian microfinance institutions are most efficient: the biodiversity index takes an average value of 20.57 in America, 11.87 in Asia and 4.75 in Africa; and that population density in 2007 was 85 people per square kilometer in Asia, 44 in Africa and 28 in America. However, since countries are not homogenous, to find the potential of economic policy to increase efficiency (and thereby reduce lending interest rates) we would need to have data on biodiversity and population for all local markets where this microfinance institutions work. This is a quest for future work. 18 V. Conclusions One of the reasons that gave rise to this paper was the claim that the high interest rate that microfinance institutions were charging was reducing the impact of their financing. Taking this as granted, our objective was to find how these rates could be reduced. Through various empirical methods, three policies -usually mentioned by policymakers- were indirectly tested. The first one is reducing the funding rate. Consistent with such recommendation, all of our estimations suggest a non-negative correlation between such rate and the lending interest rate. However, since almost 90% of all microfinance institutions of our sample had an average funding cost of 0% in real terms, there is not much room for market-driven reductions. Further, economic theory and economic history show that government intervention to reduce this price is likely to be a short-lived policy in lieu of the distortions it creates. Fostering competition is always claimed to be the best public policy to reduce the lending interest rate. However, in markets where reputation and loyalty matters, it may well happen that an increase in competition leads in the short run to changes in the loan size but not in the lending interest rate. Further, testing such policy is not easy since it is difficult to find a proxy for 1,299 microfinance institutions in 84 countries that may properly measure the intensity of competition. Furthermore, since most financial entities do not work at the national level such proxy would need to be able to measure the intensity of competition in local markets through time. We did not have the necessary information to build such a good proxy. Instead we used a variable commonly used in the literature and found that while in Asia an increase in competition leads to a reduction in the lending interest rates, in America it leads to a reduction in the average loan size. While not being the panacea to reduce lending rates, results shown here suggest that fostering competition should continue to be a public policy objective. 19 The third mechanism to reduce the lending rate consists on policies that may help increase the efficiency of these financial institutions. All our results suggest that a higher efficiency leads to lower lending interest rates. To increase efficiency, technology use and management quality need to be considered. Further, since the impact of efficiency on lending rates is increasing with the initial size of microfinance institutions, government also need to consider the possibility of fostering mergers and acquisitions in this sector. However, how much could public policy help increase efficiency? Given the lending technology that most microfinance institutions use, an answer to such question will depend on how difficult is for loan officers to reach their target clients. Thus, geographic characteristics of the territories and the spacial distribution of their clients should matter. In this regard, data at the national level may help explain why microfinance institutions are more efficient in Asia and less in Africa. But of course, countries are not homogenous and thereby the quest is to find data that could describe these features at the micro level. If we had such data, we could estimate the natural rate of efficiency of each microfinance institution and thereby learn the potential of public policy to increase efficiency and help to reduce the lending interest rate. 20 Bibliography Aleem, I. (1990), “Imperfect Information, Screening and the Costs of Informal Lending: A Study of a Rural Credit Market in Pakistan. The World Bank Economic Review, Vol. 4(3), pp. 329-349 Alexander-Tedeschi, Gwendolyn and Dean Karlan. 2006. “Microfinance Impact: Bias from Dropouts.” Unpublished manuscript, Department of Economics, Yale University. Banerjee, Abhijit and Esther Duflo. 2004. “Do Firms want to Borrow More? Testing Credit Constraints Using a Directed Lending Program.” Unpublished manuscript, Department of Economics, MIT. Beck, T., A. Demirguc-Kunt and R. Levine (2007), “Finance Inequality and the Poor”. Journal of Economic Growth, vol. 12(1), pp. 27-49. Boot, A. and A.Thakor (2000), “Can relationship banking survive competition?” Journal of Finance, Vol. 55: 679-713. Calem, P. and L. Mester, “Consumer Behavior and the Stickiness of Credit-Card Interest Rates”. American Economic Review, Vol 85(5): 1327-1336. Carbó, S. F. Rodriguez and G. Udell (2006), “Bank Market Power and SME Financing Constraints”. Working Paper 237/2006 Funcas. Cull, R., A. Demirguc-Kunt and J. Morduch (2006), “Financial performance and Outreach: A Global Analysis of Leading Microbanks”. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3827. Gonzalez, A. (2007), “Efficiency Drivers of Microfinance Institutions (MFIs): The case of Operating Costs”. MicroBanking Bulletin, Issue 15. Gonzalez, A. (2010), “Analyzing Microcredit Interest Rates”. www.themix.org Mix Data Brief No.4, Kai, H. (2009), “Competition and Wide Outreach of Microfinance Institutions”. Personal RePEc Archive 17143. Munich Levine, R. (2005), “Finance and Growth: Theory and Evidence” Handbook of Economic Growth. P. Aghion y S. Durlauf (eds.) Northe-holland Elsevier Publishers. Lewis, J. (2008), “Microloan Sharks”, http://www.ssireview.org/articles/entry/939/ Stanford Social Innovation Review. Marquez, R. (2002), “Competition Adverse Selection, and Information Dispersion in the Banking Industry”. The Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 15: 901-926. 21 Martinez, S. and A. Mody (2003), “How Foreign Participation and Market Concentration Impact Bank Spreads: Evidence from Latin America”. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Vol. 36 (3): 511-537. McIntosh, C. and Wydick, B. (2005) “Competition and microfinance” Journal of Development Economics 78, 271-298. Morduch, Jonathan. 1998. “Does Microfinance Really help the Poor? New evidence from Flagship Programs in Bangladesh”. Unpublished manuscript, Department of Economics Harvard University. Ongena, S. and D. Smith (2001), “The duration of bank relationships”. Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 61: 449-475. Petersen, M. and R. Rajan (1995), “The Effect of Credit Market Competition on Lending Relationships”. Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 110: 407-433. Pitt, M. and S. Khandker (1998), “The Impact of Group-Based Credit Programs on Poor Households in Bangladesh: Does the Gender of Participants Matter? Journal of Political Economy. Vol. 106(5): 958-996. Rosemberg, R., A. Gonzalez and S. Narain (2009), “The new Moneylenders: are the poor being exploited by high Microcredit Interest Rates”. CGAP Occasional Paper No. 15. Zarutskie, R. (2003), “Does bank competition affect how much firms can borrow? New evidence from the U.S,” en Proceedings of the 39th annual conference on Bank Structure and Competition, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, pp. 121–136. 22 Table 1 The database Continent # MFIs #Countries # obs. Average number of years operating in 2008 Africa 294 32 1,096 11.44 America 358 20 1,431 15.06 Asia 647 32 2,191 10.42 Total 1,299 84 4,718 12.43 Table 2 Distribution of some key Data during the period 2000-2008 Africa America Asia Real ROA Loan as Real ROA Loan as Real ROA Loan as interest (%) % of interest (%) % of interest (%) % of GDPpc rate (%) GDPpc rate (%) rate (%) GDPpc 1% - 4.1 - 57.6 2.8 -11.2 - 40.6 1.9 - 5.2 - 48.1 3.0 10% 10.9 - 15.9 12.3 13.1 - 4.7 5.0 9.1 - 6.5 8.2 25% 18.4 - 4.8 25.5 21.3 0.6 12.2 15.5 0.0 13.8 50% 28.2 0.8 56.6 30.9 3.0 29.3 23.3 2.5 25.4 75% 45.1 4.3 117.4 44.4 6.2 58.2 34.6 6.0 69.7 90% 64.9 8.9 252.4 63.2 10.2 103.5 50.6 10.9 164.6 99% 145.8 21.5 692.0 103.0 19.1 312.2 88.0 25.9 1,125.0 23 Table 3 Distribution of some key data during the period 2000-2008 Africa America Asia Total Funding Operating Total Funding Operating Total Funding Operating Assets Interest Cost per Assets Interest Cost per Assets Interest Cost per (1982-84 Rate dollar lent (1982-84 Rate dollar lent (1982-84 Rate dollar lent dollars) (%) dollars) (%) dollars) (%) 1% 174 0.0 0.046 862 0.0 0.049 227 0.0 0.024 10% 1,427 0.1 0.118 4,588 0.9 0.107 1,318 0.1 0.066 25% 4,341 0.8 0.172 10,181 3.1 0.141 4,379 2.1 0.115 50% 12,364 2.0 0.290 34,640 5.4 0.218 13,847 4.4 0.175 75% 54,464 3.6 0.484 135,092 7.6 0.363 45,355 7.3 0.288 90% 176, 319 6.2 0.771 464,817 9.9 0.573 162,716 10.4 0.473 99% 962,372 14.6 2.065 1,927,736 16.6 1.242 1,916,596 21.8 1.158 24 Table 4 Descriptive statistics of main variables Nominal Lending interest rate Funding cost Efficiency (in logs) Return on assets Average loan size (in logs) Competition Initial assets (in logs) Age of the financial institution Provisions as a % of assets Biodiversity Population Density Mean Maximum Minimum St. Deviation Africa America 0.42 0.42 2.58 1.50 0.01 0.02 0.27 0.21 Asia 0.35 2.01 0.03 0.18 Africa America 0.03 0.06 0.22 0.71 0 0 0.03 0.04 Asia 0.05 0.56 0 0.05 Africa America 1.23 1.47 3.95 5.08 -1.73 -0.72 0.77 0.70 Asia 1.73 7.01 -1.20 0.79 Africa America -0.02 0.02 0.83 0.53 -0.97 -0.89 0.14 0.11 Asia 0.02 0.73 -1.80 0.12 Africa America 0.19 1.15 3.39 3.88 -2.91 -2.12 1.06 0.93 Asia 0.40 4.62 -5.28 1.39 Africa America 0.015 0.057 0.046 0.149 0.0002 0.0004 0.012 0.0.46 Asia 0.036 0.238 0.00002 0.036 Africa America 8.69 9.68 13.51 14.66 0.90 4.01 1.86 1.78 Asia 8.52 15.47 0.62 1.91 Africa America 9.43 14.07 58.00 51.00 0 0 6.90 9.47 Asia 11.01 52.00 0 8.98 Africa America Asia 2.1 2.4 1.4 83.9 33.3 55.4 0 0 0 3.9 3.1 2.9 Africa America 5.94 27.00 29.22 100.00 0.13 0.89 7.00 24.01 Asia 19.20 80.96 0.17 22.37 Africa America 82.95 65.96 394.03 358.36 2.59 8.95 67.28 79.64 Asia 287.62 1229.16 1.70 352.89 25 Table 5 Dependent variable: Lending Interest Rates Africa America Asia 3 continents Ifund 1.26*** 1.11*** 0.87*** 1.04*** Effic - 0.24*** - 0.17*** - 0.16*** - 0.18*** Roa 0.76*** 0.71*** 0.73*** 0.72*** - 0.03*** - 0.04*** - 0.03*** 0.007 -0.14* -0.09 Avgloan Competition within between overall Rsquare N - 0.02** 0.04 0.34 0.66 0.65 1066 0.45 0.76 0.74 1420 0.44 0.54 0.54 2082 0.39 0.64 0.63 4568 Notes: 1.-* p<.1; ** p<.05; *** p<.01 2.- Estimation Method: Generalized Least squares. Taking into account the results provided by the Hausman test, all estimations were done with fixed effects. 3.- Dummies for each year were not included for African and Asian countries since a joint test rejected the need for them; for America and the world wide sample, the omitted year was 2000. We included a constant and five dummies to account for the type of institutions: NGO, rural bank, credit union or cooperative, bank, non- bank financial institution. The category “other” was the omitted category. Finally, we also included variables to describe the statue of the country’s legal rights and credit information. The parameters of these dummies are not reported here. 26 Table 6 Dependent variable: Lending Interest Rates With heterogeneous impacts Africa America Asia 3 continents Ifund 1.78 1.07*** 0.68** 0.86*** Ifund * initial assets - 0.04 0.01 0.01 0.02 Effic 0.05 - 0.38*** - 0.02 - 0.08*** Effic * age - 0.01* 0.01*** - 0.01*** - 0.0003 - 0.04*** 0.02*** - 0.02*** - 0.01*** 0.003** - 0.001*** 0.002*** - 0.006*** 0.002*** - 0.006*** - 0.002*** Effic* initial assets Effic*initial assets*age Initial assets*age 0.0007*** Roa 0.43 0.19 0.51*** 0.49*** Roa*initial assets 0.04 0.070** 0.02 0.03** Age 0.05** - 0.02*** 0.05*** 0.01*** - 0.01 - 0.02*** - 0.05*** - 0.03*** - 0.02 - 0.20** - 0.11 Avgloan Competition R-sq 0.59 within between overall 0.37 0.35 0.34 0.47 0.63 0.61 0.46 0.31 0.36 0.40 0.51 0.52 N 1053 1410 2053 4516 Notes: 1.-* p<.1; ** p<.05; *** p<.01 2.- Estimation Method: Generalized Least squares. In all regressions a constant was included. Taking into account the results provided by the Hausman test, all estimations were done with fixed effects. 3.- Dummies for each year were not included for African and Asian countries since a joint test rejected the need for them; for America and the world wide sample, the omitted year was 2000. We included a constant and five dummies to account for the type of institutions: NGO, rural bank, credit union or cooperative, bank, non- bank financial institution. The category “other” was the omitted category. Finally, we also included variables to describe the statue of the country’s legal rights and credit information. The parameters of these dummies are not reported here. 27 Table 7 Simultaneous Estimations Dependent Variable Africa America Asia 3 continents Ifund 0.71*** 1.30*** 0.42*** 0.86*** Effic - 0.21*** - 0.10** - 0.07*** - 0.12*** Roa - 0.11 - 0.89*** Iloan Avgloan Competition 0.09*** - 1.27 0.10*** - 0.20** - 0.02* - 0.08*** - 0.03*** 0.39 - 0.43*** - 0.56*** Roa Iloan 0.59*** 1.03*** 0.45*** 0.77*** Ifund - 0.79*** - 0.95*** - 0.50*** - 0.76*** Effic 0.22*** 0.25*** 0.11*** 0.19*** - 0.000*** - 0.000*** - 0.000 - 0.89*** - 1.13*** - 1.03*** - 0.95*** Effic 0.92*** 0.96*** 0.0004 0.60*** Age 0.01*** 0.004*** 0.008** 0.01*** Outreach Provisions 0.0001*** Avgloan Competition Iloan N - 5.65 2,73*** 1,053 - 2.91** - 2,26** - 1.60** 0.11 - 5.32*** - 0.52 1,419 2,049 4,511 Notes: 1.-* p<.1; ** p<.05; *** p<.01 2.- Estimation Method: Three stage least squares. 3.- We included a constant, a dummy for each year and for each country. The omitted categories were the year 2000, Benin (Africa), Argentina (America), and Afghanistan (Asia). Similar to the last table, we included in the equation that had the lending interest rate as dependent variable, five dummies to account for the type of institutions and two variables to describe the statue of the country’s legal rights and credit information. 4.- For the 3 continents estimation we included a constant, a dummy for each year, a dummy for each country, being Afghanistan the omitted category and a dummy for each continent with Africa as the omitted one. 28 Figure 1 Average Efficiency by Size Distribution of Microfinance Institutions 4 3.5 3 2.5 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 -0.5 1% 5% 10% 25% 50% 75% 90% 95% 99% -1 Africa America Asia 29 Notes 1 However, these lenders usually lacked specialization in credit transactions, operated in small local markets and were unable to reach economies of scale. Thus, they were unlikely to become a cheap source of funding. Leaders in the microfinance industry learned how informal lenders operated and thanks to the support of international organizations and governments, were able to build institutions with governance schemes that help to minimize principal-agent problems and used technologies that allow them to achieve economies of scope. As default rates declined and group lending and sequential loans were developed, the number of microfinance institutions grew. Adding to these improvements, the introduction of credit bureaus and the build-up of an appropriate regulatory framework has certainly help to develop –in many countries- a very dynamic microfinance industry. 2 The Microfinance Information Exchange is considered the most important source for objective and unbiased microfinance data and analysis. They provide unparalleled access to operational, financial and social performance information on more than 1,900 MFIs covering 92 million borrowers globally. Once collected, all the data is review for its coherence and consistency, and reclassified to comply with International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). 3 Even though we had data for 2009, we decided not to include it because of the singularity of the economic and financial crisis that started in the second half of 2008. 4 There is a caveat to such proxy. If an institution has put in place a growth strategy it may well happen that in the short run their costs may be growing faster than their lending operations. This of course would not mean that they are less efficient than others. 5 We tried with both proxies for efficiency and found that results improved when we used as proxy the inverse of operational cost without adjustments. The correlation between both proxies within each continent was about 0.6. 6 The log of initial assets had the following distribution: Percentiles Africa America Asia 4.489 5.136 4.437 1% 6.169 7.627 5.961 10% 7.540 8.516 7.397 25% 8.696 9.679 8.589 50% 9.868 10.781 9.690 75% 11.178 12.031 10.853 90% 12.460 13.691 13.761 99% 7 This index is a weighted average of terrestrial (80%) and marine (20%) characteristics of each country. The terrestrial features capture the distribution of species and threats to them, and the variety of climates and ecological factors in their territory. The source of this data is: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ER.BDV.TOTL.XQ 30