Helen MacGillivray

advertisement

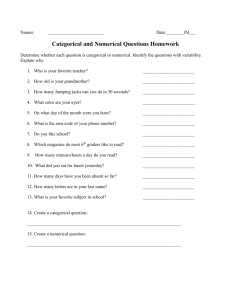

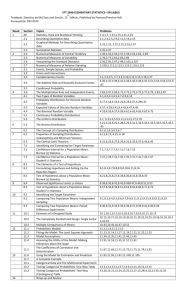

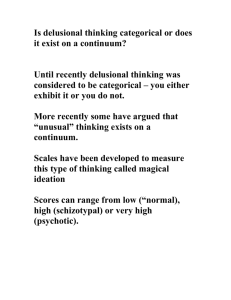

Developing statistical thinking capabilities for postgraduates across disciplines Helen MacGillivray Vice-president, International Statistical Institute Immediate past-president, IASE (International Association for Statistics Education) Senior Learning and Teaching Fellow Past president & honorary life member, Statistical Society of Australia Inc Outline of presentation Symposia in Statistical Thinking for Postgraduates across disciplines Why, when, how What From participants Statistical thinking and data investigations Let’s plan a data investigation! From statistical consultants and statistical educators How research questions become statistical investigations Key statistical thinking and hands-on planning Key points from symposia on statistical analyses What about secondary data? Results from pre-symposia questionnaire Implications for ug How can universities develop/support statistics for pg’s Models and ideas: feedback QUT Maths Access Centre established 2004 Aim: to develop and provide university-wide learning support for students in any area for which numeracy, mathematical and/or statistical confidence are needed. The programmes gradually developed to include: drop-in facilities (3 campuses), with resources & schedule of duty tutors. student-driven support sessions for a range of courses or topics. provision & development of general and course-specific resources and questionnaires for student self-diagnostic support. areas supported include engineering, chemistry, nursing, education, human movement, psychology, maths, stats an apprenticeship-model tutor development program with mentoring and training for talented undergraduates collaboration with academic & learning support programs. website and Facebook. research: data collected and analysed links with UK; ALTC leadership project 2006-2007 In 2013 became part of STIMulate – Science, IT, Maths & Stats Like other maths and stats learning support centres, QUTMAC oriented to helping at undergraduate level, esp. first years & anyone with lack of confidence in background or foundation skills But In agreeing to providing some funds (very modest), DVC recommended “doing something” for postgraduates !! In 2005, Manager of Research Students Centre approached me asking if I could help in statistics for commencing postgraduates. Me, very warily: * pg’s tend to say they want individual help, & * people often think pg’s need workshops in specific advanced methods, but, before any of that, my experience is that * they need to understand role of statistics in research, & * they need sufficient understanding of core statistical data analysis methods to have some confidence for their research & possibly discipline-specific or more advanced methods Manager: exactly! (me, thinks: wonderful to have someone who understands!) So me & the manager plotted & planned a trial to see if “Statistical Thinking for Postgraduates Across Disciplines” would fly. Trial & evaluation, 2005 Offered trial initial session, described by Session Objectives: Learning about Your statistical thinking Planning a statistics-friendly data investigation. Statistical questions and research questions. Choosing, using and interpreting statistical graphs and procedures The session will refer to real data investigations in contexts that do not depend on discipline-specific knowledge. A pre-session “diagnostic” questionnaire sent to registrants to help them (& me!) included stats literacy questions from PhD work by Therese Wilson (now Maths and Stats Coordinator STIMulate) main emphasis on questions on core stats methods oriented to misconceptions & even mistakes often seen in pg/research in other disciplines see later for details & some interesting results Trial & evaluation, 2005 74 registered, from all faculties, 51 attended Included staff, particularly from Health Focus on Planning an investigation Importance of identifying variables & their types, and subjects (“design your spreadsheet for your raw data”) Turning research questions into statistical questions General principles of estimation & error of estimation, prediction, modelling, fitting, testing, checking assumptions Choice of graphs What is needed to choose analysis method(s) Trial & evaluation, 2005 Evaluation included asking what they’d like for next session & in future 38 evaluations (across faculties) with lots of comments 66% agreed or strongly agreed it addressed their information needs Surprisingly large given it was just an introduction 85-90% agreed or strongly agreed that Objectives were clear Content was relevant Well structured & presented They learned something useful to their pg research Trial & evaluation, 2005 Comments generally indicated that they wanted more ranged from having very little background (“What’s a ttest?” “What’s ANOVA?”) to having one ug stats course wanted basics: “chisq, ANOVA, regression, confounders,” “what to use when & where” “when to use different graphs” General comments such as: “a pleasure to attend, very informative & delivered in a very friendly, comfortable, clear manner” “basic info made easy to understand – should teach health stats” Conclusions: yes, worth doing, and yes, they did want to understand basics from a research point of view. And they wanted it delivered in clear, simple & friendly manner Follow-up session: trial & evaluation, 2005 Session Objectives Focus on using key techniques of chisquare, ANOVA, and multiple regression in detecting what is happening in a dataset, including understanding of statistical hypothesis testing and its value for research, and awareness of possible problems and how to use diagnostics to check for problems. Techniques demonstrated and discussed through real datasets with interesting statistical features that are explored within context, emphasizing the importance of understanding the data context. Follow-up to the first one, focussing on topics most commonly requested by the participants. 26 attended: almost unanimous approval - “very useful” “wonderful” “very good pace”; strong support for planned series of 4 symposia Symposia in Statistical Thinking for Postgraduates 2006 Series of 4 symposia, 2.5 hours each (incl coffee break!) given twice a year. Timetable, registrations & evaluations done by Research Students Centre 40-50 registrations each time; approx 65%-70% attendance Types of comments & approval ratings generally consistent over the years (approx 90% approval) Some staff in first couple of years; now mostly pg students in their first semester/year, masters as well as PhD. Across faculties Pre-symposia questionnaire retained with slight adaptations Associated SPSS workshops 2007- Symposia in Statistical Thinking for Postgraduates Aim: assist pg students with statistical understanding essential to planning, carrying out and analysing data investigations using core statistical tools. For those with some statistical background For those with little statistical background help to see what can be achieved with core statistical tools. For others help consolidate and improve confidence in using core statistical tools in real & sometimes challenging applications, & provide indicators of further statistical tools you may wish to learn. help identify and fill in gaps in your statistical knowledge and understanding. Series modularised - optional questionnaire organised under the headings of the four symposia. Real datasets in contexts that do not require discipline-specific knowledge, but sufficiently complex to allow demonstration of choice, use, interpretation and synthesis of statistical tools and thinking. Computer output is used throughout the symposia but the symposia do not include teaching the use of a particular statistical package (See SPSS workshops). Symposia in Statistical Thinking for Postgraduates Titles & key points 1. Planning investigations, handling & exploring data Research question(s) planning pilot Identify subjects, variables, types planning 2. Categorical data Estimating proportions; error of estimation; general concepts of confidence intervals Statistical hypothesis testing. Turning research questions into statistical questions 1 & 2 categorical variables & chisq test More than two? 3. Continuous response, categorical predictors Confidence interval for mean vs. prediction/tolerance interval for individual values ANOVA, experimental design, interactions, residuals, assumptions, diagnostics, transformations More? Symposia in Statistical Thinking for Postgraduates Titles & key points 4. Continuous response, quantitative predictors. Regression (multiple) Models, interpreting output, residual plots & diagnostics Changing model Dependence & interaction in regression R-sq & cautions Categorical predictors? General linear model More? Participants ask questions throughout. Referring to their own context within symposia facilitates statistical understanding for all. Any extra discussions/points depend on group & questions. Developments & SPSS w’shops Questions and opportunities to find out areas of participants help to orient the important ad hoc examples Aspects known to be needed from start require even more emphasis and attention - but benefits are great Variables & their types, subjects Scientific hypotheses vs. statistical hypotheses Scientific experiments vs. statistical investigations Essential roles of graphs in exploration & diagnostics Dangers of one-explanatory-variable-at-a-time Worst problem from standard/conventional introductory courses Ban ‘two-sample t’ in research! Beware of correlations! Coping with discipline requirements/habits without compromising statistics Three SPSS hands-on workshops linked with & immediately following symposia topics 2, 3 & 4 Limited to 30 registrants < 20 participants Some participant comments Fantastic! I arrived being “scared of numbers” and left the session feeling empowered. It may sound crazy but I really “enjoyed” this learning experience. Thanks. …you motivated me to want to understand I’m starting to understand. Really oriented to our needs I did not understand it (regression) but I realize now what I need to know. Really good to refresh knowledge of statistics & learn how to apply to our research. Found ANOVA interesting. Clear, hit points. I really enjoyed it. It is helping me to understand stats well. I become clearer about the purpose of using statistics for my research. Some participant comments …..a joy to be there ….real-life examples of the data and the interpretation of the results was simply great It was fantastic. ………. explained this heavy subject with appropriate examples. Now I am confident to use the techniques I had learnt in analyzing my data It is becoming more and more interesting. I would definitely use the knowledge in the evaluation phase of my experiments. Excellent resources. Very useful for research students. I found that it was a very good and succinct summary of the approach needed for different data sets and in different types of analysis…. …. being a science student ……. I am very happy I attended all sessions as I found them to be a very helpful revision of where and how different tests should be used and has given me enormous confidence in reading published work and also considering stats while designing my experiments. Only a few negative comments: Pre-2007, wanted SPSS workshops Others from extremes: “too fast” “more time to digest” “more depth please” From consultant statisticians Barnett (1976) describes statisticians as “translators and communicators” (1986) “we see, tied up together, the role of the statistician as consultant, consultancy as the stimulus for research in statistics, and consultancy as the basis for teaching statistics”. From (extensive) literature on statistical consulting, comes emphasis on ‘greater statistics’ and the whole data investigation process From consultant statisticians Cameron (2009) considers desirable key components of university-based training of a statistician to prepare for a research consulting career of “entwined collaboration” and “serial collaboration” consults what many “wide and experienced” statisticians have written (Box, 1976, Chambers, 1993) identifies formulating a problem so that it can be tackled statistically preparing data (including planning, collecting, organising and validating) analysing data presenting information from data researching the interplay of observation, experiment and theory. From consultant statisticians Kenett & Thyregod (2005) describe the 5 steps in statistical consulting problem elicitation data collection and/or aggregation data analysis using statistical methods formulation of findings & consequences presentation of findings and conclusions/recommendations. “important to take part in collection of data, or at least have the opportunity to watch data being collected or generated.” “Our long-term objective is to encourage academic courses to cover the full 1–5 cycle.” From statistical educators Statistical education advances advocating such approaches for all disciplines started across the world over the past two decades Both statistical consultants and statistical educators also champion Garfield (1995) comments that authentic experiential learning as vital constructivist approaches. students will understand material only after they have constructed their own meaning for what they are learning. I add to that: Students understand the whole data investigation process only when they have lived it. This applies to all disciplines. Students understand probabilistic thinking and its modeling only when they construct meaning that links with everyday contexts and with data, and builds on previous experiences. Data investigations: school & tertiary RSS Centre for Statistical Education problem-solving cycle (from 1970’s) Plan Collect Process Discuss Authentic learning of data investigations: tertiary My courses,1994-2011: semester-long free-choice full data investigation embedded in introductory statistics courses in all engineering, science and mainstream mathematics and statistics programs Student-centred “inquiry” (Anderson and Sungur, 2010) “Inquiry oriented learning” IOL in Science (Kirkup et al, 2010) Authentic student-centred discovery of K&T’s Steps 1-5 Research questions statistical questions Early software use helps students discover power of statistics in many-variabled & messy real world situations Thousands of projects, datasets and examples “Excellent foundation for statistical research” (PhD student) embody everyday experiences, constructivist principles and “emotionally & cognitively supportive” problem-solving environment Gal et al (1997) Extract from Symposium 1 Planning and design of data investigations involve identifying the topics of interest identifying the variables to be observed identifying the subjects of the study planning the practicalities Planning and design of data investigations The planning of collection of data can include design of experiments or studies in a lab situation design of field experiments or studies – outside a lab situation design of an observational study design of surveys In all quantitative problem-solving, identification of variables is important To plan your own data investigation or understand others, and to choose and use statistical techniques, identification of variables is essential Just a few examples of practical challenges What do we want to find out about? What can we find out about? What can we observe? What can we measure? Can we measure what we want. Is there anything we should observe/record ….. just in case? Should we do a pilot study or preliminary experiment? Beware the traps of the rigid version of the scientific method! Might start with a single research question, but must turn into investigation Many/most discoveries are made by observation of something unexpected of something during investigating something else and/or thinking outside the original box Don’t be a slave to identifying & investigating a single idea/thought/hypothesis – investigate objectively Research hypothesis vs statistical hypothesis Example of research hypothesis “There are little green men out there!” Statistical hypothesis “There are no little green men out there” Qualitative & quantitative - Not versus Not alternatives Form the continuum of investigation Consider the continuum of interviews, questionnaires, surveys In qualitative, often searching for what to measure & how to measure … how to describe, how to classify, what is different and what is similar In quantitative, must know and understand measures and variables, and how procedures depend on this knowledge Some general points Don’t pre-categorise variables such as time, age, monetary amounts, etc, without good reason and thought Identifying variables ALWAYS helps in planning identifying subjects of the study identifies what the rows of your spreadsheet will correspond to can also help in deciding what you are interested in Report how, when, where and possible problems of the data collection Keep raw data. Importance of randomness In an experiment In a survey Design, controls and random allocation within design Randomness essential to investigate causation Question/instruction design AND random selection (possibly within sampling frame for more sophisticated designs) AND obtaining responses Randomness essential to infer to population In an observational study Of what can we consider our data to be randomly representative with respect to questions of interest? Random representativeness of our data with respect to questions of interest Data entry - much more to it than one may think – and value in the thinking about it Each variable has a column Each “observational/experimental” unit/item/subject has a row. Identifying “experimental unit” = each row in spreadsheet corresponds to …...? Enter in order of observation - in case you want to check for any trends or changes in conditions. Some examples of data collected by tertiary students Egg crush test (A. Warr and S.Yu, 2001) The students designed an experiment to test the strength of egg shells of various types and brands. Research hypothesis: brown eggs are stronger than white Their home-made apparatus held the egg steady on its side under a container that they gradually filled with water until the shell first cracked. Some eggs could not be used. They obtained 202 observations Variables: Response variable = crush load (=weight of water when egg cracked Other variables: colour, brand, housing, egg length, egg width Egg crush apparatus Egg crush procedure Egg crush after the experiment Some examples of data collected by tertiary students Bike track (Ford, Hungerford, Johnson and Swain) Students wanted to investigate use of a bike track. Motivation: speeds of cyclists vs pedestrian usage They carried out their study on 1 day from 8am-6pm. They recorded time of day, speed, type of travel, direction, and gender. Time of day was recorded in 15min intervals due to “collecting pressure”. They used one collection form for each 15mins. After exploring the data, they further grouped the times into am peak, am off-peak, lunch, pm off-peak and pm peak. Types of data - types of variables Considering types of data is also considering types of variables In all quantitative problem-solving identification of variables is important. In statistics, identification of the TYPES of variables helps in choosing appropriate methods of exploring and analysing data. Variables are of two broad types: discrete and continuous. Discrete variables take individual or separated values. Discrete variables are further divided into categorical and count. Categorical data fall into categories which can be named or coded. Codes have no meaning in themselves - just labels. Count data record a number of items, events, people etc. Some categorical variables have a natural ordering of their categories. The order of the codes matter but not their actual values e.g. 1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, …. 5=strongly agree. Called ordinal variables. Continuous variables Usually have units Examples include time, height, weight, distance, age, amounts of money ... Money? Consider exchange rates, hourly wage ‘Height is 1.5m’ = height is between 1.45m and 1.50m. ‘Height is 1.52m’ = height is between 1.515m and 1.525m. Continuous variables take values in intervals – typically continuous data have values given “to the nearest….” Variables can be Discrete Categorical Nominal Continuous Count Ordinal Other words that are sometimes used for data are “qualitative” and “quantitative”: categorical are qualitative data continuous and count are quantitative data. Graphs and tables help us organise, explore, highlight features and present data Identifying types of variables helps us in choosing types of plots and graphs Categorical: tables, barcharts, (piecharts) Piecharts can do only single categorical variables Continuous: dotplots, histograms, stem-andleaf plots, boxplots, scatterplots, time series Count: often very small (tables, barcharts) or large (dotplots, histograms, stem-and-leaf, boxplots) Beware: incorrect 3D graphs; barcharts that start above 0; scatterplots that start at 0 Let’s design a data investigation! What’s of interest Identify variables Identify subjects of study (observations are per what?) Practicalities – how, when, where, who. Have we forgotten anything? Anything else we should record? What will our spreadsheet look like? What do we need to check in our pilot? Random representativeness of our data? Let’s design a data investigation Groups choose a topic & what to investigate (at least 4 variables), identify variables and subjects, outline data collection, spreadsheet, conduct preliminary pilot, report. 1. Stretchiness of snakes (confectionery snakes!) OR 2. “When people clasp their hands, they tend to have left thumb on top” OR 3. How often do people blink? “Various studies have shown the average person blinks at a rate of approximately 20 to 25 times per minute.” From symposium 2: Categorical data Proportions are everywhere! Estimating proportions: conditional proportions One categorical variable – testing a set of %’s Testing statistical hypotheses – understanding the principles and p-values; interpreting p-values Two categorical variables – testing independence Confidence intervals for proportions Confidence intervals as estimates of parameters More than two categorical variables? Estimated proportions are everywhere! “Rich keenest on hand-out for insulation” In a story by Eloise Gibson in the New Zealand Herald on 15th September, 2009, (http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&o bjectid=10597307 ) reported the results of an online survey conducted by the Business Council for Sustainable Development of 1578 homeowners on floor and ceiling insulation subsidies under which home owners must pay up to $3500 themselves. The newspaper report includes the information that “Homeowners making more than $200,000 a year made up only 1 per cent of respondents, but 45 per cent of them planned to get help with home insulation costs, as did 35 per cent of those making $70,000 to $100,000 and 29 per cent of those on $100,000 and $150,000.” One categorical variable - testing a set of %’s A City Council brochure states that on a typical summer weekend, users of a pedestrian bridge fall into the following age groups. Age group 0-10 11-20 21-30 31-40 41-50 51-60 61-70 70+ Percentage of users 5 20 40 15 8 5 5 2 One typical summer weekend, 100 people were observed crossing the bridge. Which of the data sets given below would cause you to question the information in the brochure? Age group % of users Age group % of users Age group % of users 0-10 5 0-10 10 0-10 7 11-20 13 11-20 20 11-20 19 21-30 32 21-30 45 21-30 43 31-40 14 31-40 10 31-40 13 41-50 13 41-50 5 41-50 10 51-60 12 51-60 5 51-60 3 61-70 11 61-70 3 61-70 4 71+ 0 71+ 2 71+ 1 Two categorical variables A study considered the aspect that cocaine addicts need the drug to feel pleasure. Perhaps giving them a medicine that fights depression will help them stay off cocaine. A three-year study compared an antidepressant called desipramine with lithium (a standard treatment for cocaine addiction) and a placebo. The subjects were 95 chronic users of cocaine who wanted to break their drug habit. Each treatment had subjects randomly assigned to it. The results are below. Is there evidence of any treatment effect? Relapse No relapse Desipramine 13 18 Lithium 22 10 Placebo 24 8 Two categorical variables Lift or stairs? In 2007, a group of engineering students decided to observe the busway stop at the Brisbane Cultural Centre to investigate the use of stairs or lift to provide information on design issues for public transport stops. They recorded data on users in three time periods – morning peak hour, afternoon off-peak, and evening peak hour. For each person using the bus station in these times, they recorded a number of variables, including gender, direction of travel (up or down), and whether stairs or lift was used. The table shows the observed frequencies for choices of lift or stairs when going up at the bus station in the three different times of day. Do the data provide evidence that the choice for those going up depends on the time of day? Choice Time Lift Stairs Total Morning_peak 222 210 432 Off-peak 232 130 362 Evening_peak 300 213 513 Total 754 553 1307 Testing hypotheses: research vs null No matter what the research hypothesis, the statistical null hypothesis is that ‘nothing’s going on’, ‘there’s no effect’. The ‘null’ reduces the unknowns or complexity The research hypothesis is often the alternative hypothesis. So we are trying to see if there is sufficient evidence to say that There is something going on We need to go to a more complicated model There is evidence of the research hypothesis Testing statistical hypotheses: p-value Need a test statistic to summarise data or the ‘difference’ between data and model We find the chance of obtaining our data (strictly speaking the value of the test statistic) IF there’s ‘nothing going on’ – that is, assuming the null. This probability is called the p-value of the test for our data. A small p-value says that we had little chance of getting our data if the assumption is true So a small p-value says our data do not tend to support the assumption. Testing statistical hypotheses: p-value A not-small p-value says there was a reasonable chance of getting our data if null true, so insufficient evidence against null, for alternative. Sliding scale of strength of evidence p-value < 0.01 (or 1% if you prefer): very strong evidence against the null hypothesis p-value between approx 0.01 and 0.03: strong or reasonably strong evidence against the null p-value between approx 0.04 and 0.06: evidence (or reasonable evidence) against null p-value between approx 0.06 and 0.1: slight or some evidence against null p-value > 0.1: not sufficient evidence against the null Just think where you’d be prepared to stand up and say there’s evidence against the null “Rich keenest on hand-out for insulation” The only proportion for which we can obtain a confidence interval in this example, is the proportion of homeowners making more than $200,000 a year who plan to get help with home insulation. For these homeowners, the data we have is n = 15.78 (1% of 1578) which we’ll take as 16, and X = 7 (45% of 1% of 1578). Based on these data, a 95% confidence interval is: (19.4%, 68%) From symposium 3: Analysis of Variance: continuous response, categorical predictors Confidence interval for mean and tolerance/prediction interval for individual values Continuous response and 1 categorical predictor: 1-way ANOVA (2 sample t), multiple comparisons Continuous response and categorical predictors: ANOVA, interaction, residual plots, assumptions, diagnostics, modelling, interpreting. R-sq. Experimental design Where to go for more The experiments/investigations Car prices Car prices were collected from www.carpoint.com.au on one day for one model from one manufacturer. Amongst other variables, the year of manufacture (2001-2005) and whether the advertiser was a dealer or private, were noted. Also state of sale and colour of car. Three possible predictors. The experiments/investigations Soluble aspirin To investigate the time to dissolve different types of soluble aspirin tablets, an experiment was conducted with 5 brands, using two water temperatures (room/fridge), two pH’s of water (neutral/acidic), and two water types (normal/mineral). Aspirin was classified as dissolved once it had broken up and dissociated from the surface of the water. Four experimental factors. Research questions: are brands different? does water type, temp or pH matter? Egg crush Three categorical and two continuous predictors Research hypothesis: brown are stronger than white The experiments/investigations Burn Rate of Candles Party candles are long and thin and available in four colours. The interest was in whether time to burn is affected by colour and angle. To hold the candles, two rows of holes were drilled in a block of wood. The first row was vertical to the surface of the block, whereas the second row was drilled at a 60 angle. Four packets were tested. There are 24 candles in a packet - 6 each of pink, yellow, white and blue. A stopwatch was started as the first candle was lit, and then they were lit at intervals of 10 seconds. They were then put out with a wet sponge after they had each burned for 5 minutes. The same person lit all of the candles with the same technique and same lighter (gas). The experiment was done all on one day, to avoid any climatic effects. The length and weight before burning were measured, and the length after burning. That is, the rate of burning was measured by amount of burning that happened in 5 mins. Length before & after, weight before, colour, packet, angle Research question: do colours burn differently to each other? Key points in analysing 1. Never comment before checking residuals! 2. Interaction Example: Car Prices Interaction between seller and year looks at whether the difference in average prices between dealers and private sellers changes over the years. Must have replication to be able to include interaction. Choose a context to explain interaction. 3. Multiple comparisons are used to look at which means are different e.g. which years are different in car prices. Note: Big data can have a lot of variables or a lot of observations or both. Key points: 1 predictor at a time mistakes Dissolving aspirin 1 predictor at a time: only some evidence that temp matters (strange?) no evidence that pH matters (what?) strong evidence that water type matters strong evidence that brands are different When all predictors used together & interaction included: strong evidence that each factor matters, averaged over the others; evidence that different brands react differently to pH and to type of water, but not to temperature Can you see a possible problem in this experiment? Key points: 1 predictor at a time mistakes Egg crush experiment 1 predictor at a time: strong evidence that colour matters strong evidence that housing matters strong evidence that brands are different When all predictors used together & interaction included: strong evidence that brand and housing matter, but no evidence that colour matters, averaged over others. And no evidence that difference between caged and free range depends on brand. Can you think why? How could you investigate? Key points: Understanding confidence intervals for means What is the most common mistake in interpreting confidence intervals for means? Example: the pH’s of 20 rainfalls in an area gave: * a 95% confidence interval for mean pH of (5, 5.6); * a 95% prediction interval for 90% of the rainfalls of (3.82, 6.78) Confounding and experimental design In the candle burning experiment, the students used 3 packets of candles for the vertical ones and 1 packet for the ones at 60 degrees. What is the problem? From symposium 4: continuous response, quantitative predictors; then general linear model Fitting model, interpreting output, residual plots and diagnostics Effects of a variable after allowing for/after fitting/in presence of others Changing model: allowing for curvature Dependence and interaction in multiple regression “Unusual” observations R-square and caution with correlation Can we include categorical predictors? Indicators Transforming data General linear models Examples Nutritional content of breakfast cereals There are many different breakfast cereals with different purposes. Measures that are commonly provided per 100 gms serve include energy (in KJ, standing for KiloJoules), protein (in gms), carbohydrate (in gms), dietary fibre (in gms), amount of iron (in mgs). How are they related? And how closely are they related? Examples What affects textbook prices? Data were collected on all textbooks from a university bookshop. Course notes were not included nor were general reference books. Where multiple editions of a book were available, only the most recent was included. Each book was classified according to whether the cover was hard or soft, if it came with a CD and whether it had colour or not. Each book was weighed, its thickness measured, and its price and year of publication noted. The main response variable in this dataset is price. There are three categorical variables, each with two categories (cover type, CD, and colour), two other continuous variables (weight, thickness) and the variable year of publication which could be used as a quantitative or a categorical variable. Examples: general linear model; “Analysis of covariance” Egg crush Burn time of candles Secondary data Example: Plasma Study investigating the determinants of plasma concentrations. 315 observations on the following 14 variables Age (years) Sex Smoking status. Never, Former or Current Smoker Quetelet (weight/(height2)) Vitamin Use. Yes, fairly often, Yes, not often or No Calories consumed per day Grams of fat consumed per day Grams of fibre consumed per day Number of alcoholic drinks consumed per week Cholesterol consumed (mg/day) Dietary beta-carotene consumed (mcg/day) Dietary retinol consumed (mcg/day) Plasma beta-carotene (ng/mL) Plasma Retinol (ng/mL) Secondary data Example: Very low birth weight infants Study on infants with birth weights less than 1600 grams collected at Duke University Medical Center. Collected from 1981-1987, including 671 instances of very low birth weights. Information collected on 27 variables Variables: Date of birth (admission) plus a fraction of the year Date of death or discharge plus a fraction of the year Hospital stay (days) lowest pH in first 4 days of life Platelet count Race Birth weight (grams) Gestational age (weeks) born at Duke or transported If multiple gestation observed Duration of labour (hours) If mother treated with MgSO4 Secondary data Example: Very low birth weight infants (cont) Variables: If mother treated with beta-methasone If mother treated with beta-adrenergic drug Delivery abdominal or vaginal Appearance, Pulse, Grimace, Activity, Respiration (APGAR) at one minute If assisted ventilation used If pneumothorax occurred If patent ductus arteriosus detected If on supplied oxygen at 30 days Periventricular hemorrhage, absent, possible or definite Intraventricular hemorrhage, absent, possible or definite intraparenchymal echodensity, absent, possible or definite Year of birth plus a fraction of the year, eg. 84:591 is August 3, 1984 Sex If patient alive or dead Some pre-symposia questionnaire results (DK = don’t know or no response) 9 stat lit questions: scores from 2 to 9, median 6 2D vs 3D graphs: 34% correct, 20% DK Identifying continuous variables: 9% correct, 11% DK Identifying categorical variables: 20% correct, 9% DK Identifying subjects: 23% correct, 11% DK Interpreting boxplots (out of 7): scores from 0 to 7, median 5 Incorrect coding of N/A: 60% correct, 14% DK Estimating conditional probabilities (2 questions): 80% correct 71% correct, 6% DK Some pre-symposia questionnaire results Situtation for (chisq) test of independence Identify which test needed: State null: Interpret p-value (in general terms): 23% correct, 43% DK 20% correct, 31% DK 63% correct, 31% DK Situtation for testing mean: Identify null: Interpret p-value (in general terms): 26% correct, 66% DK 57% correct, 34% DK Identify problem with multiple t-tests: 6% correct, 51% DK Compare multiple t-tests with multiple predictor ANOVA: 3% correct, 54% DK Problem of doing 1-way ANOVA on carefully designed randomised block experiment: 6% correct, 71% DK Some pre-symposia questionnaire results Identify mistake in interpreting confidence interval for mean as prediction interval for individual values (quality control context): 6% correct, 66% DK Identify problem in judging regression model just on p-value & R-sq: 0% correct, 69% DK Identify problem in using categorical predictor (>2 categories) in regression: 23% correct, 66% DK Identify problem in using ordinal variable as response in regression: 17% correct, 71% DK Some implications for ug curricula Service courses in statistics should go to many variables ASAP & avoid focus on 2-sample & simple linear regression Experiential learning Whole data investigation process Investigations/projects should avoid design-forprocedure Focus on essential concepts of statistical inference & data modelling Contexts must not dominate statistical learning Contexts must be familiar or readily accessible to students Must use technology as used in practice of statistics Real data and no toy datasets Staff research interests must be controlled Beware teacher-centred or too-complex case studies How can universities develop/support statistics for pg’s? Courses for credit plus rationed consultations? Statistical consultants with faculty ‘buy-in’? Online plus rationed consultation? Consider a tree analogy for combining development of graduate capabilities and support for pg work Curriculum of symposia described here is common ‘trunk’ of tree ‘Branches’ are special topics ‘Leaves’ are (rationed) individual consultations with student and supervisor Thank you and here’s to statistics!