Exploring Creative Forms of Writings, Priscilla Oh

advertisement

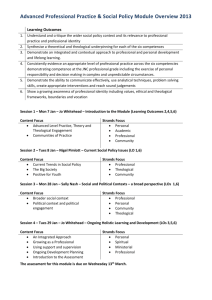

Summer Institute of Theology and Disability 2015 Negotiating Boundaries Exploring Creative Forms of Writings in the Context of Mental Illness Presented by Priscilla Oh Introduction “ I became a great question to myself.” - Augustine Outline Writing as Calling and Journey Theology by Heart Negotiating Emotional Challenges in the Context of Mental Illness Reflexive Practice Exploring Creative forms of writings The purpose of this workshop is to develop ways in which our personal experiences in particular, living with mental illness or disabilities or a shared life with mental illness might be expressed creatively and theologically. Through writing our stories, we want to create a space of reflecting our lives, writing as a tool to interpret and understand the emotional aspects of our life in the context of mental illness. Writing as Calling & Journey Before we get into deep conversation, I would like to introduce various forms of writings as a theological method which includes writing theological memoir, autoethnography and life-writing. I want us to have the opportunity to approach our life and reflect upon the development of the self which entails exploring our sense of the self, identity and purpose of our lives. As Christians we also want to raise our consciousness in particular importance in understanding of God in our lives in a meaningful way. Writing as Calling and Journey Autoethnography – a kind of qualitative research method that considers personal experience at the core of investigation critically in connection to cultural and social practice and the method acknowledges an intricate relationship with others Theological Memoir – “ a history and interpretation of a person’s life written by the person who experienced it, considered in relation to its spiritual foundations.” (Walton 2014) Writing our stories… Writing our stories… Writing our stories can reinforce the belief that life is meaningful. Through writing about and reflecting on our life stories, and discussing them in the groups, we can be helped to come to terms with our lives. It helps to overcome a victim perspective, and to meet the future changes with increased confidence and competence. (Randall and Kenyon, 2001; Staude, 2008, p.252) Writing about one’s life may attain emotional release, catharsis, or self-healing, feeling oneself from a painful or inadequately integrated past experience, such as loss of loved ones. Writing as a journey of discovery Writing theological memoir and personal life-writings can generate a personal journey to understanding and knowing oneself consciously connecting to historical cultural background. Autobiographical – theological – life writing can be identified as a journey of discovery and identified as the “ autobiographical imperative” in composing ourselves Theology by Heart “ God is experienced as immanent, personal and intimate, speaking through the interiority of human experience. Record of such experience – journaling, autobiography, psychotherapeutic account of self – are vehicles of theological reflection and construction.” (Graham and Walton, 2005) Theological reflection – a theological activity which enables people of faith to give an account of the values and traditions that underpin their values and choices and deepens their understanding. Confessions –Augustine’s Life-Writing In his Confessions, Augustine found himself as an internal quest of his soul, and he found a very difficult quest of himself: “ How could the mind hope to contain the mystery of God? The house of my soul is too narrow for thee,” and he wrote, “ I do not grasp all that I am.” (Confessions, Bk 10) A successful attempt to unify and cohere experience in a single narrative that consolidates the author in relation to God. (Anderson, 2004) Like Augustine’s Confessions, telling our stories and writing about them coherently will function in creating a healing coherence where we can assemble our disparate stories of our life into a story that can be told about a person who is beloved or significant in our lives to us. (Walton, 2014) “What community do I belong to ?” : Clarifying religious identity and location in self-accounts “ I suspect that when Modern Americans ask, “What is sacred?” They are really asking “What place is mine? What community do I belong to” (Norris 1995) Telling you who we are can be a challenging for us to see the areas of our lives that are hidden and unaware of. Kathleen Norris charts her life in Dakota: a Spiritual Geography. “What community do I belong to?” Norris’ autobiography clarifies and relates to a variety of placement and identity in herself account. She identifies her physical location, Dakota, as a place where she actively affiliated to the church community and participated in the discipline of neighboring Monastery and her vocation as a poet. In her writing, Norris was eager to clarify why being where she is has positive effects on her in order to commend placement by her readers. By affirming a religious identity with a physical location, she also believes that dwelling places do carry moral and spiritual consequences. For her, the affirmation of place relation to her religious identity is inseparable. (Kort 2012) Theological Memoir “Hannah’s Child” Similar to Augustine’s Confessions, Stanley Hauerwas testifies his life-time project about what it means to be a Christian theologian in his self-account, Hannah’s Child. “ In this entrancing memoir, Stanley Hauerwas reflects on what he sees as the successes and failures of his life as one of the most celebrated theological ethicists of his time. It is, of course, the accounts of his perceived personal failures that are the most testing and moving: what breaks and stops even his own best motivations and intentions are the stuff of profound Christian reflection. This little autobiography follows triumphantly in the Augustinian tradition of “ confessions”. (Sarah Coakly) Theological Memoir Hauerwas’s memoir is candid and even humorous at times. In particular, his reflection on his relationships are honest and profoundly moving. In his memoir, Hauerwas is not shy of his conviction as a narrative based formed Christian. As he courageously opens up on a life-long engagement of a theological question, what it means to be a Christian, he attempts God’s presence known every aspect of life with challenge, contingency and consequences. On the other side of his tale, he tells us of a secret story of his marriage living with a spouse suffering from manic depression. In retrospect, he tells us about the disruptive, uncontrollable and painful memories of his marriage life as a truthful tale. In this memoir, Hauerwas reveals the emotional dimension of how he negotiated his spouse’s illness situation and shows distinctive contingencies that he faced as a husband. Emotional Dimensions in facing mental illness situation The unique grief felt by family members remains a total mystery to so many of our neighbours. Such a loss is not recognised. (Govig 1999, p. 26) “Grief is the normal but bewildering cluster of ordinary human emotions arising in response to significant loss, intensified and complicated by the relationship to the person or the object lost.” (Anderson 2010, p.127) Emotional dimensions in the context of mental illness “ Emotional anomie” – To make sense of a beloved one’s mental illness in a family environment, often relatives, families and spouses experience confusion. Prior to psychiatric diagnosis, caregivers and families have no normative basis for understanding the behaviour of a mentally ill person. They simply do not know what to feel. David Karp appropriately called this process as ‘ emotional anomie’. (Karp 2001, p. 7585) When the family is involved with the process of accepting a member with a mental illness, as a result of attempting to provide continual care for the beloved one they often continue with sorrow and defeat. The experience of living closely with a person suffering from a long term mental illness Most families are affected by a family member’s mental illness situation to a higher degree and they feel like they are not living their own life. They found themselves in difficulty to have balanced relationship. They struggle to get their voice heard within the health care system. They have difficulty in re-evaluating their circumstances. (Stijernswärd and Östman 2008, p. 358-367) Implications of these burden factors are the most predictive factors for the effect of the household routine disruption and predictor of the psychological distress. (Noh and Turner, 1987, p.23) An example of developing an evocative writing style I began to recognise the sign of helplessness and my inner struggles in facing my friend’s mental illness situation, I started to look for an emotional space where I can express my emotional burdens within the boundary of my ordinary life. Writing autoethnography actually helps to reflect on my relationship to her but also my response to the illness situation as well. What was helpful for me about this process was that I was able to express my experience as a form of lament from a massive writing that I produced while constructing my stories. Here is an example: “ A Lament for a Friend” A Lament for a Friend I. Home To my delight, though you come to me in darkness, grief and loneliness, you have become companion of the light that rises in Christ However apprehensive and anxious you were, I welcomed you. Though you fear making mistakes, you would consent to make yourself at home. It was my delight Waking up in the morning I hear the sound of birds singing. How refreshing! To my amazement, you came to me with the gloomy face and you said, “ foreboding”. What a day of start for you dear friend. A Lament for a Friend II. In the Winter In the solitude of winter, I walked along the street of New Haven. Your life withdrawn into a hospital ward, having known fully how difficult it was for you then, I hoped that you would be out of the ward soon. At the end of December, I found you at the back of your bedroom, your eyes turned to me and said, “ I could not sleep.” I knew then you were downtrodden. Dear Friend, On that day, the morning was bright under the still fall of snow, whiteness touched the world perfectly. It was such a beautiful start of the day. I remembered what our neighbour Theodore said to me, “ I love the frosty and bright winter of Ipswich. Isn’t this a beautiful morning?” But for you, you were in darkness and pain. A Lament for a Friend III. We Prayed Alas! Out of silence, the words come. I read Psalm 13, “How long must I struggle with anguish in my soul, with sorrow in my heart every day?” “How long will my enemy have the upper hand?” I exclaimed, “ How long O Lord must I endure? Help my countenance.” “ Turn to me and answer me O Lord. Restore the sparkle of my eyes,” we prayed. “ Lord, give us hope, hear our cries and comfort us,” we prayed Reflexive Practice Auto (theo)biographical Theology Reflexivity – the exercise of reflexivity is the key for writing autobiographical, life-writing or theological memoir in theological refection. Reflexivity is an intentional and disciplined form of reflection on how the personal, social and cultural context of the author/ researcher not only affects what is researched, that is, the choice of particular field of study, but also the way that the research is conducted. Reflexive Practice in Writings Reflexivity is described as, ‘ a mode of knowing which accepts the impossibility of the researcher standing outside of the research field and seeks to incorporate that knowledge corporately and effectively. (Swinton and Mowatt 2006, p.59) My approach to auto/theo graphical life-writing is based on the assumption that accepting the personal and social situation of knowing includes accepting our involvement of belief and faith. This is an important process of writing as a Christian theologian, it sets out to see how our own theologies are situated in personal and social context as a subjective enterprise where our theology begins to shape. Writing our stories theologically can not only be a starting point of the healing process as a way of knowing, but also as a mode of illuminating that we can hope for renewing our mind and for transformation.