Richard II - University of Warwick

advertisement

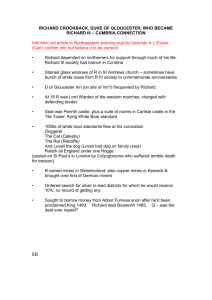

Richard II ‘such is the breath of kings’ Seems, madam? Nay, it is. I know not ‘seems’. ...These indeed ‘seem’, For they are actions that a man might play; But I have that within which passeth show. These but the trappings and the suits of woe. (Hamlet 1.2.76-86) A king of shreds and patches… (Hamlet 3.4.93) The play’s the thing Wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the King. (Hamlet 2.2.581-582) Tears in his eyes, distraction in’s aspect, A broken voice, and his whole function suiting With forms to his conceit? And all for nothing… (Hamlet 2.2.532-534) And as imagination bodies forth The forms of things unknown, the poet’s pen Turns them to shapes, and gives to airy nothing A local habitation and a name. (A Midsummer Night’s Dream 5.1.14-17) But what are kings, when regiment is gone, But perfect shadows in a sunshine day? (Edward II 5.1.26-27) The best in this kind are but shadows, and the worst are no worse if imagination mend them. (A Midsummer Night’s Dream 5.1.208-209) If we shadows have offended… (A Midsummer Night’s Dream Epilogue 1) He of you all that most desires my blood, And will be called the murderer of a king, Take it. What, are you moved? Pity you me? (Edward II 5.1.100-102) King Edward III (1312-1377) Edward The Black Prince Lionel Duke of Clarence John of Gaunt Duke of Lancaster Edmund Langley Thomas of Woodstock Duke of York Duke of Gloucester (1330-1376) (1338-1368) (1340-1399) (1341-1402) Richard of Bordeaux King Richard II (1367-1400) Henry Bolingbroke Earl of Derby, Duke of Hereford; later, Duke of Lancaster; then King Henry IV (1367-1413) (1355-1397) JOHN OF GAUNT Alas, the part I had in Gloucester’s blood Doth more solicit me than your exclaims To stir against the butchers of his life. But since correction lieth in those hands Which made the fault that we cannot correct, Put we our quarrel in the will of heaven, Who, when they see the hours ripe on earth, Will rain hot vengeance on offenders’ heads... God’s is the quarrel; for God’s substitute, His deputy anointed in his sight, Hath caused his death; the which if wrongfully, Let heaven revenge, for I may never lift An angry arm against his minister. (1.2.1-8, 37-41) [So Gaunt gets his son, Henry Bolingbroke, to challenge Thomas Mowbray (who committed the murder on Richard’s behalf) to a duel.] BOLINGBROKE Look what I speak, my life shall prove it true: That Mowbray hath received eight thousand nobles In name of lendings for your highness’ soldiers, The which he hath detained for lewd employments, Like a false traitor and injurious villain. Besides I say, and will in battle prove, Or here or elsewhere, to the furthest verge That ever was surveyed by English eye, That all the treasons for these eighteen years Complotted and contrivèd in this land Fetch from false Mowbray their first head and spring. Further I say, and further will maintain Upon his bad life, to make all this good, That he did plot the Duke of Gloucester’s death, Suggest his soon-believing adversaries, And consequently, like a traitor-coward, Sluiced out his innocent soul through streams of blood; Which blood, like sacrificing Abel’s, cries Even from the tongueless caverns of the earth To me for justice and rough chastisement. And, by the glorious worth of my descent, This arm shall do it or this life be spent. (1.1.87-108) [On the halting of the trial by combat:] [I]n Act I of [Richard II] Shakespeare incorporates from Holinshed Richard’s sudden and unexplained method of staying the trial by combat for which such elaborate preparations have been made. Lacking comment from Richard himself and without any form of guidance from a character who as pointer or chorus could underscore the point, the spectator is provided no significant motivation for this action. (Larry S. Champion, ‘The Function of Mowbray: Shakespeare's Maturing Artistry in Richard II’, Shakespeare Quarterly 26.1 (1975), 3-7; p. 7) In Froissart, the King calls of the battle beforehand to avoid being accused by his subjects of secretly aiming at Bolingbroke’s destruction (6.314). Shakespeare leaves Richard’s motivation for stopping the combat unclear; equally ambiguous is the question of whether his action in throwing down the warder is premeditated or spontaneous. (Charles R. Forker, note to 1.3.121-2 in The Arden Shakespeare: King Richard II (London: Thomson Learning, 2002), p. 217) There can be little doubt that [the real, historical] Richard’s intervention had spoiled what promised to be the outstanding chivalric occasion of the year– indeed, of the age; and the disappointment can be sensed in the writings of the chroniclers. The difficulty for Richard, however, was that a resolution to the issue by arms would have exposed him to intolerable difficulties. A victory or Norfolk [Thomas Mowbray] would have revived criticism that he wanted to stifle enquiry into Gloucester’s murder, while a victory for Hereford would have added to the renown of a man whom he increasingly disliked and whom by now he probably also feared. (Nigel Saul, Richard II (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), pp. 401-2) [On the banishment of Mowbray and Bolingbroke:] Richard, at the outset presumably unaware of the charges Bolingbroke is to bring against Norfolk (even Gaunt tells the King that he has not been able to sift the argument), acts with magnanimity and grace as he addresses each of his subjects, warmly calling Bolingbroke ‘our cousin’ at the same time as he observes that it will take a serious matter indeed to provoke ‘a thought of ill’ in Norfolk. Even after Bolingbroke states his charges, Richard assures Mowbray that the hearing will be fair and objective despite Bolingbroke‘s royal kinship. With more gall than discretion, however, Mowbray undeniably implicates the King as ultimately responsible for the murder… Mowbray assumes no doubt that Bolingbroke - realizing where his charge now falls - will not dare pursue the issue further. This, of course, is Mowbray’s cardinal error; his unbridled tongue will shortly cost him the price of perpetual banishment… Mowbray's words are, of course, no less critical to the relationship between Richard and Bolingbroke. For, from this moment, Bolingbroke’s charge of murder extends to the King, and his refusal to ‘throw up his gage’ (and thus retract his charges against Norfolk) Richard must now take as a direct affront to the royal prerogative, indeed as treason itself. The King’s subsequent blessing for Hereford at Coventry is a rather obvious attempt at overcompensation for the sake of the public image. But what follows should surprise no one. Bolingbroke's banishment is as dramatically credible as that of Mowbray, even without the subsequent scene in which Shakespeare draws the more specific foil relationship between the royal cousins. (Champion pp. 5-6) KING RICHARD Now put it, God, in his physician’s mind To help him to his grave immediately. The lining of his coffers shall make coats To deck our soldiers for these Irish wars. Come, gentlemen, let’s all go visit him. Pray God we may make haste and come too late! (1.4.58-63) Throughout the first three acts of Richard II, Richard attempted to play a double game; he used “Realpolitik” when it was convenient, but he attempted to maintain his theoretical footing in the medieval laws of succession and kingship. Even in the midst of his machinations, Richard never clearly understood the dynamics or the consequences of power politics. Most significantly, he failed to articulate the medieval interdependence of law and power... Richard’s reign in Shakespeare’s play rests on a basis of law without the power necessary to substantiate that law. In his attempts at power, however, he abandons the appearance of law completely, and thus invalidates the very system that made him king and kept him king. Once he himself violates the law, his reign has absolutely no basis of authority.’ (Henry Jacobs, ‘Prophecy and Ideology in Shakespeare’s Richard II’, South Atlantic Review 51 (1986), pp. 3-17; 12) KING RICHARD We were not born to sue, but to command. (1.1.196) The nicest irony of Richard’s language is that he is sincere. He may have moments of bluster, but he does sincerely believe in the divinity of his kingship, sincerely believes his downfall to be solely the work of traitors, and is sincerely sorry for himself. Nor is this “acting”. Certainly Richard has a histrionic style, a weakness for melodrama and a fondness for the limelight, but he is not consciously playing a role. What we see – and more importantly what we hear – is what he is. (John Halverson, ‘The Lamentable Comedy of Richard II’, English Literary Renaissance 24 (1994), pp. 343-369; 360) The idea of Divine Right is actually presented in the play as a historical myth...which develops and emerges from the defeat of the monarchy. Richard dramatises that myth as the monarchy itself dissolves; he affirms it most powerfully as his power disappears; and as his effective rule declines, his tragic myth exerts ever more powerful pressures on the imaginations of those responsible for his defeat. (Graham Holderness, Shakespeare Recycled: The Making of Historical Drama (Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1992), p. 71) One can say that Richard has the name of kingship, whereas Bullingbrook is the man who can gather and wield its power... On the one side, an authority signified in names, forms and ceremony; on the other, an authority enacted, empowered and embodied. (Robert S. Knapp, ‘Shakespearean Authority’ in Shakespeare’s History Plays: Richard II to Henry V (New Casebooks), (London: Macmillan, 1992), pp. 87-102; 88-89) [A] king who ruled by divine right was also, in theory and in practice, subject to the law; he was to rule according to the law, and his power derived from the law… [T]he keystone of a commonwealth is not the king’s royal prerogative, his power, or his supremacy, but the well-being of those he rules. By contrast, a landlord sees his people as slaves, as the means by which he enlarges himself; they exist only to increase his wealth and profit… [T]his relationship between landlord and people is antithetical to the idea of a commonwealth… For Richard to act like a landlord is not to diminish the royal prerogative, then, but to act as though the royal prerogative allows a king to do anything he wishes. (Donna B. Hamilton, ‘The State of Law in Richard II’, Shakespeare Quarterly 34 (1983), 5-17; pp. 6-7) BOLINGBROKE How long a time lies in one little word! Four lagging winters and four wanton springs End in a word: such is the breath of kings. (1.3.206-8) [Kantorowicz, quoting from the Commentaries of Reports (London: S. Brooke, 1816) of the sixteenth-century lawyer Edmund Plowden (15181585), illustrates the contemporary theory of the King’s Two Bodies:] “The King has two Capacities, for he has two Bodies, the one whereof is a Body natural, consisting of natural Members as every other Man has, and in this he is subject to Passions and Death as other Men are; the other is a Body politic, and the Members thereof are his Subjects, and he and his Subjects together compose the Corporation...and he is incorporated with them, and they with him, and he is the Head, and they are the Members, and he has the sole Government of them; and this Body is not subject to Passions as the other is, nor to Death, for as to this Body the King never dies, and his natural Death is not called in our Law...the Death of the King, but the Demise of the King, not signifying by the word (Demise) that the Body politic of the King is dead, but that there is a separation of the two Bodies, and that the Body politic is transferred and conveyed over from the Body natural now dead, or now removed from the Dignity royal, to another Body natural. So that it signifies a Removal of the Body politic of the King of this Realm from one Body natural to another.” [Kantorowicz comments on Richard’s return from Ireland (3.2):] There is as yet no split in Richard when, on his return from Ireland, he kisses the soil of his kingdom... What he expounds is, in fact, the indelible character of the king’s body politic, god-like or angel-like... Man’s breath appears to Richard as something inconsistent with kingship... This glorious image of kingship “By the Grace of God” does not last. It slowly fades, as the bad tidings trickle in...The Universal called “Kingship” begins to disintegrate; its transcendental “Reality,” its objective truth and god-like existence, so brilliant shortly before, pales into a nothing, a nomen... It is as though it has dawned upon Richard that his vicariate of the God Christ might imply also a vicariate of the man Jesus, and that he, the royal “deputy elected by the Lord,” might have to follow his divine Master also in his human humiliation and take the cross... The king that “never dies” here has been replaced by the king that always dies and suffers death more cruelly than other mortals.’ (Ernst Kantorowicz, The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Medieval Political Theology (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957), pp. 13, 27-30) KING RICHARD Here, cousin, seize the crown. Here, cousin. On this side my hand, on that side thine. Now is this golden crown like a deep well That owes two buckets filling one another, The emptier ever dancing in the air, The other down, unseen, and full of water. That bucket down and full of tears am I, Drinking my griefs, whilst you mount up on high. (4.1.172179) He beats me and I rail at him. O worthy satisfaction! Would it were otherwise: that I could beat him whilst he railed at me. (Troilus and Cressida 2.3.2-4) Northumberland’s demand that Richard respond to the commons’ suit implies that Parliament can and does act without the king, and, indeed, that Parliament takes precedence over the king and can dictate terms to him. Such apparent corroboration of views expressed in another text that genuinely offended the state suggests why Richard II’s Parliament/deposition scene may have been censored. (Cyndia Susan Clegg, ‘“By the choise and inuitation of al the realme”: Richard II and Elizabethan Press Censorship’, Shakespeare Quarterly 48 (1997), 432-448; p. 445) BOLINGBROKE Are you contented to resign the crown? KING RICHARD Ay, no; no, ay; for I must nothing be; Therefore no no, for I resign to thee. Now mark me how I will undo myself. (4.1.190-193) Although Richard’s feminine self-indulgence and histrionic narcissism disqualify him for political action, Richard and not Bullingbrook was the “well-graced actor” in Shakespeare’s theatre: no acting company would give the smaller and less demanding role of Bullingbrook to its best actor and deny him the chance to play the leading role of Richard. Even in the deposition scene, where the represented action depicts Bullingbrook’s acquisition of Richard’s power, Richard dominates the stage. He deposes himself and makes long and eloquent speeches about his complicated emotional responses to the action... Taking the glass and contemplating his own image, he meditates aloud for sixteen lines about his face. The instrument of feminine vanity becomes the means of theatrical empowerment, for it demands that all eyes in the playhouse, including Richard’s own, will be fixed on Richard’s face. (Jean E. Howard and Phyllis Rackin, Engendering a Nation: A Feminist Account of Shakespeare’s English Histories (London: Routledge, 1997), pp. 154-155) The [history] plays reveal that the pageantry and props of rule are largely factitious, that their value is strategic rather than sacramental. Neither custom nor grace preserves the crown, though their ceremonies often dress it gaudily... Knowledge here is power, or at least power depends on the knowledge that power is power. When Richard finally learns the lesson of this brutal tautology it is too late to translate it into action. All he can do is force Henry publicly to enact the reality of their exchange of power rather than the privileged Lancastrian version that Henry wishes to have staged before Parliament. Though Richard can affect the formalization of the exchange, he cannot, however, prevent the exchange itself. (David Scott Kastan, ‘Proud Majesty Made a Subject: Shakespeare and the Spectacle of Rule’, Shakespeare Quarterly 37 (1986), pp. 459-475; 469, 471) Ay, no; no, ay Yes no; no, yes = = = = Yes, no; no, yes Yes, I am contented to resign the crown Actually, no I’m not Actually, yes I am no ‘ay’ / no ‘I’: for I must nothing be / for [my] ‘ay’ must nothing be Therefore no no = therefore I have no no, I cannot say no OR Therefore no, no = therefore I can only speak in negations, being nothing (a no-thing, a thing of ‘no’s) for I resign to thee / for my ‘ay’ I resign to thee / for my ‘I’ (my self) I resign to thee / for I re-sign (re-inscribe) my ‘I’ and ‘ay’ to thee At Essex’s Star Chamber trial for treason in February 1601, Cecil charged that the Earl “had been devising five or six years to be King of England...and meant to slip into Her Majesty’s place” by insinuating himself “into favour” with “the Puritans”, “the Papists” and “the people and soldiers” in general. The linking of Shakespeare’s tragedy with Essex was obviously after the fact and, from the dramatist’s point of view, fortuitous, but it has nevertheless affected interpretation of the play’s politics. The relevant facts may be summarised as follows. On 7 February 1601, the day before Essex staged his abortive rebellion, a group of the Earl’s supporters paid Shakespeare’s company forty shillings to revive an old play on “the deoposing and killing of King Richard II” at the Globe – generally considered to have been Shakespeare’s tragedy. The conspirators apparently believed that the drama would serve as effective propaganda for their treasonable enterprise. [See Hammer, below, for a refutation of this point.] When Augustine Phillips, one of the shareholders of the Chamberlain’s Men, was summoned to answer for the actors, he pleaded that they had been reluctant to put on the drama, it being “so old and so long out of use that they should have a small company at it”, but had nevertheless been “content to play it” as requested. That Shakespeare and his fellows were innocent of any seditious design is clear from their having escaped punishment on this occasion and also from the fact that they were playing at court only days after Essex’s trial. (Charles R. Forker, ‘Introduction’, The Arden Shakespeare: Richard II, ed. Charles R. Forker (London: Thomson Learning, 2002), pp. 9-10 [T]he play performed on Saturday, 7 February, had no direct connection with what happened the following day because those events were unforeseen on Saturday afternoon, let alone a day or so earlier when the performance was commissioned. Instead, the play was clearly ordered with an eye to Essex’s entry into the court, which was planned for the following weekend. This renders moot some of the more extravagant claims that have been made about the connection between drama and rebellion. It is true that the official Declaration of the practises & treasons attempted by Robert late earl of Essex and his complices (penned by Francis Bacon) ties the play performed on Saturday afternoon to the events of Sunday, but this assertion by the government reflects the needs of the official case against Essex and his co-accused, not what those who commissioned the play actually intended. (Paul E. J. Hammer, ‘Shakespeare’s Richard II, the Play of 7 February 1601, and the Essex Rising’, Shakespeare Quarterly 59.1 (2008), 1-35; p. 18) [W]hat of Queen Elizabeth's own alleged claim that “I am Richard II”? This...plays a major part in the traditional narrative that associates Shakespeare's Richard II with the Earl of Essex. The story comes from a manuscript held by the Lambarde family – quite a different source than Privy Council records. It tells, in the third person, of William Lambarde, who on August 4, 1601, six months after Essex's death, was presenting the queen with a list of manuscripts contained in the Tower. Her eye fell upon the “Richard II” subdivision of the listing and she remarked, “I am Richard II. know ye not that?” Lambarde, according to the manuscript, responded, “Such a wicked imagination was determined and attempted by a most unkind Gent. the most adorned creature that ever your majestie made” – meaning, perhaps, that Essex had tried to make a Richard II out of Queen Elizabeth. The manuscript then tells us that the queen answered, “He that will forget God, will also forget his benefactors; this tragedy was played 40tie times in open streets and houses.” Let us waive here an interesting problem in the hermeneutics of historical narrative to grant the manuscript's accuracy and timeliness – Lambarde himself died on August 19, 1601, fifteen days after the interview. Let us also grant for the moment the possibility that Queen Elizabeth was personally disturbed by the Richard II story. Let us even grant the improbable supposition that plays (by the Lord Chamberlain's Servants?) were acted (free) in the public streets and that in 1601 Richard II, though old, was acted forty times. [See Hammer, below, for another interpretation of this phrase.] Given all of this, was Shakespeare’s play the force behind the queen's sensitivity to the Richard II model? Such need not have been the case. As early as January 9, 1578, Sir Francis Knollys, and at some time before 1588, Henry Lord Hunsdon (future patron of Shakespeare's company) each wrote remarks protesting that he would not give flattering advice to his sovereign, both expressing this sentiment by saying that they would not play the part of “Richard the Second's men.” The Richard II model was an old one. (Leeds Barroll, ‘A New History for Shakespeare and His Time’, Shakespeare Quarterly 39 (1988), 441-464; pp. 447-448) If the text can actually be trusted, I would argue that Elizabeth and Lambarde both refer to the official interpretation of the Essex Rising in which Essex was portrayed as aspiring to the crown and in which the queen herself was cast as being at risk of suffering the same fate as Richard II. Lambarde dutifully comments that such a prospect — attempting to overthrow and kill an anointed sovereign — could only have been the product of “a wicked imagination” and that this seemed all the more shocking because of the earl’s former status as the queen’s leading favorite. Elizabeth attributes Essex’s actions to his failure to properly understand his place in God’s ordered universe, which consequently prompted him to act toward her with a total disregard for the reverence and gratitude which a beneficiary should properly display toward a benefactor. Although she uses the metaphor of a play being performed multiple times, it seems improbable that the queen actually means a specific play here. Just as she offers an appropriately biblical round number (“forty”) to indicate “many,” Elizabeth’s use of the play image instead reflects a very common metaphor. The word “tragedy” is, in fact, by far the most frequent term by which Essex’s contemporaries described his fall and death because the earl’s fate seemed to follow the classical trajectory of a tragedy. Elizabeth’s bitterness about Essex’s conduct, however, adds an additional layer. Essex not only forgot his duty to his royal benefactor but also repeatedly displayed his hubristic ingratitude and selfpromotion “in open streets and houses” — that is, both publicly for the commons to admire and privately in the houses of well-to-do friends and followers… Elizabeth’s comment to Lambarde was not about the play performed in February 1601 — or, indeed, any particular play — but her own understanding of how her former favorite had come to such a tragic end. (Hammer, pp. 24-25)