Soci 101: MTWThF 8:00-8:50am in Room CC3452

advertisement

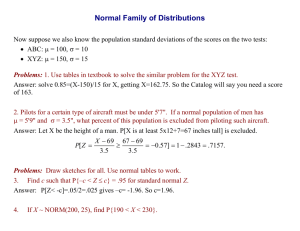

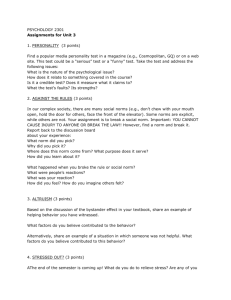

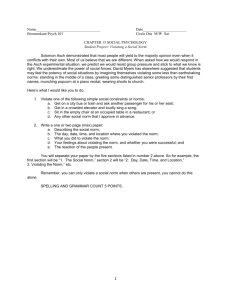

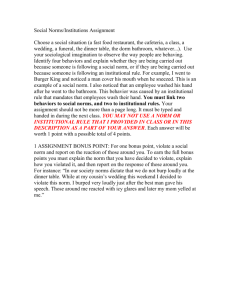

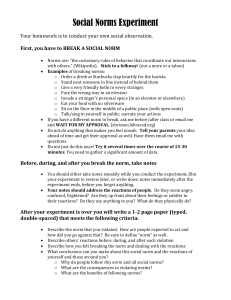

SOCIOLOGY 101 SYLLABUS - INTRODUCTION TO SOCIOLOGY North Seattle Community College, autumn 2013 Contact Information Julie McNalley – Please call me Julie. julie.mcnalley@seattlecolleges.edu Soci 101: MTWThF 8:00-8:50am in Room CC3452 I will arrive a few minutes early to class every day; I am also available by appointment. Email is the best way to reach me. Course Description This course is designed as a general introduction to the concepts, theories, and methods of sociology. Sociologists study how social forces (such as the economy, the education system, racial and ethnic relations, etc.) shape people's lives and experiences and how individuals, in turn, affect and shape the societies in which they live. We will cover a variety of topics, among them education, culture, social inequality, gender, social class, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and global stratification. Our focus will be on conditions in the U.S., taking into account this nation's cultural and economic diversity. This will involve comparisons of the experiences of social groups within the U.S., particularly on the basis of race and ethnicity, social class, and gender. To place U.S. conditions into a broader global context, we will also make comparisons to other nations. I hope that this course will provide you with a greater understanding of the world in which we live and of your own location within it. Learning Outcomes By the end of this course, you should be able to explain the basic concepts and theories of sociology distinguish between the sociological and the individualistic perspective discuss the impact of a variety of social forces, and explain how your own life and the lives of others are influenced by them explore the ways in which people influence social structures and processes question understandings of people and society based on personal experience, media portrayals, or "common sense" find and evaluate information to critically analyze controversies about society identify ways in which race/ethnicity, social class, and gender affect your daily life and are basic components of social institutions articulate the usefulness of taking a global perspective when analyzing social issues evaluate your own place in this society and in the world Texts Required: all articles are available through the NSCC library online or freely accessible online How this course works This course follows an active learning and peer instruction approach. That means you get to read, think, talk and write on your own and with your classmates, rather than sitting and listening to me lecture. If you’re not used to learning like this it may feel very different at first – you do the learning up front rather than cramming for a test or exam. But it’s worth it - in today’s work world for professional jobs you will be expected to know how to work in a team, have strong interpersonal skills, and communicate well orally and in writing. Besides being more fun and allowing you to learn more deeply, this approach to your course will help you hone those excellent workplace skills. The rule of thumb for college-level courses is to devote at least three hours per week for each academic credit associated with the course. For a five-credit course, this means 15 hours per week is the average amount of time that you should spend on readings, discussions, and other class activities. In this course you will be expected to do a lot more work up front than you normally do, and come to class prepared to think, talk, and write. But the bonus will be that you will probably not have to take any notes, and your grade will be based on many types of assessments that allow you to show what you have learned and what you can do with your new knowledge. If you do the work and keep up, you’ll do well and enjoy the process. Attendance Get your money’s worth: come to class. Attendance is a part of your grade – and you can’t participate if you’re not here! Even on tests and assignments, there is a strong link between showing up, participating and doing well. Participation in Discussions For a productive discussion, participants must: Make explicit connections to the material to demonstrate that you have read, understood, and thought deeply about these issues. Try to avoid being guided simply by your personal experience or "common sense." You can use experiences or common sense to illustrate a point related to sociology, but it should not be a substitute for social science data nor for critical thinking. 1. Respond to other students. 2. Use the sociological rather than an individualistic perspective. 3. Pose questions/observations that will initiate discussions related to the topic. 4. Be respectful and supportive of other participants in the discussion, yet intellectually challenging (i.e., questioning, stimulating). It is fine to disagree with each other (I'm sure we will do so at times), but we should clearly state the basis for that disagreement by discussing the strengths and weaknesses of the position we are criticizing (not of the person). Course Readings The assigned readings typically vary between 25 and 60 pages per week. You cannot get a good grade for the course if you do not do the readings. Even if we don’t specifically discuss each reading in class, they are part of the preparation you need in order to participate fully. Readings should be completed BEFORE the date indicated on the course schedule. Grading Assignments and Grading – THIS IS TENTATIVE! Attendance 1pt each day 2 50 points Section quizzes 5pts each Norm violation experience and write-up (4-5 pages) Midterm Low income management exercise write-up (1-2 pages) Final Total possible score 50 points 50 points 50 points 50 points 50 points 300 points Final Grades Seattle Community Colleges use numerical grading on a 4.0 scale. Your final grade will be calculated as a proportion of the highest score in the class. I will calculate percentages of the highest score and locate each student's score on a grid as a proportion of highest score. For example, if the highest score in the class is a 285, then 95% of 285 is 271. All students with scores between 271 and 284 will earn a 3.9. In contrast, 60% of 285 is 171. 171 will be the lowest passing score for the class. 3.9-4.0= 97-100% = A 3.5-3.8 = 93- 96% = A3.2-3.4 = 89- 92% = B+ 2.9-3.1 = 85- 88% = B 2.5-2.8 = 81- 84% = B2.2-2.4 = 77- 80% = C+ 1.9-2.1 = 73-76% = C 1.5-1.8 = 69-72% = C1.2-1.4 = 65-68% = D+ 1.0-1.1 = 61-64% = D 0.0 = <60% = E Regarding Assigned Work The two big assignments are due at the beginning of the class period of the due date ELECTRONICALLY. Use normal margins, Times New Roman 12 pt or Arial 10 pt. I will look at rough drafts and provide feedback. Just ask! If you do not understand any element of any assignment, please ask me for clarification before the assignment is due. No late work will be accepted without prior approval. “Prior approval” means letting me know ahead of time the circumstances that will cause your work to come in late. It also means suggesting ahead of time an alternate schedule to complete the work. However, please see the next item. Beyond an enormous family or health emergency, there is no good reason for a late assignment. Asking for Assistance Please feel free to ask me for assistance with assignments, readings, or other course materials at any time during the quarter. Should you fall behind in your performance, contact me early on so we can try to determine the problem(s) and make adjustments before it is too late. I check email regularly and should be able to get back to you within 24 hours. I’d also be happy to meet you in person. If you require an accommodation for a disability, contact the Disability Services office by phone at (206) 934-3697, TTY at (206) 934-0079 modem, or email at ds@seattlecolleges.edu. I also encourage you to contact me if I can be of additional help and/or if you would like to 3 inform me of any disabilities, concerns, or accommodation-needs. You can also visit The Loft Writing Center located on the top floor of the library building, (206) 934-0164. Do Your OWN Work Plagiarism: Plagiarism occurs when someone uses another person’s words or ideas without giving appropriate credit. Plagiarism is grounds for denial of credit for the assignment. If you are not sure, give credit. It is perfectly okay to use other people’s ideas to support your own arguments in many cases – BUT YOU MUST GIVE CREDIT. Ownership: The work that you turn in under your name is expected to be your original work, written for this course and to the specification of the assignment. Although you are encouraged to seek feedback on your writing from others, it must be demonstrably and essentially your own. Save drafts, outlines, and other preliminary steps toward your finished work, just in case a question of ownership arises. College Records Reminder: It is in your best interest to keep ALL of your college work, the work from this class included. At the very least, keep the syllabus and major course assignments. It is not unheard of to be asked to show coursework when you transfer to a 4-year institution. Quizzes, Paragraphs, the Midterm and the Final Exam Assignments There are two assignments to complete and turn in. a. Norm Violation Exercise – Can you bear to be different? The object of this exercise is to practice seeing “normal” behaviors from a sociological perspective and to write a paper describing and analyzing the experience. TO DO: With a partner, experience observing and violating a norm. TO TURN IN: A four-page paper describing and analyzing your norm-violation experience. With a partner, choose a norm to violate. For example, the way people stand in elevators, the distance two people maintain when they are talking or sitting, which utensils you use to eat certain foods, etc. Make sure that you choose a true norm, not just a silly or absurd behavior (there is a difference). Here are the steps you should take to do the exercise: 1. Go together to observe the norm, but without disrupting the normal processes. Try to identify the ways people behave when the norm is followed. This is your control group. 2. Choose who will be a violator and an observer. The observer pretends not to know the violator and watches for the reactions of the other people, while the partner is violating the norm. Watch carefully so you can compare reactions to the first observation. 3. Switch places and try it again. You may need to take some time to find three separate opportunities to observe your norm in action. 4 4. Now, write a description of this experience. Both partners should write their own paper about each role (you were both an observer and a violator). Your paper should be about four pages and have two main sections. a. Tell the story of the norm violation: set the scene and fill in all important details (did the time of day matter, the weather?). i. What were the reactions of the people around you? ii. What can you tell us about the people that might make a difference in the way they reacted (age, social class, race, sex) - think sociologically? iii. What other factors might have played into the situation (general mood, location)? iv. Explain how you went about breaking the norm. v. How were the reactions different each time? vi. Did your age, social class, race, sex play into the reactions? vii. How did you feel as both the observer and the violator? b. Discuss the power of social norms as reflected in the personal difficulty you may have experienced in purposefully violating one. i. If you had little or no trouble, consider why some norms may be easy to violate and others difficult. ii. Does this difference depend on social sanctions? iii. What made you select the norm you selected? iv. What if you had selected a different norm? Examples of norm violations: 1. Violating someone’s personal space by standing too near or sitting too near. 2. Facing other riders while standing in an elevator. 3. Dressing very formally for a casual event, or vice-versa. 4. Eating with inappropriate utensils. NOTE: Do not select norm violations that will cause you to break laws or put yourself or others in danger! If you are not sure, please run your ideas by me first. b. Low Income Management Exercise – What does it take to survive? The object of this exercise is to help you understand the effects of social class on opportunity in our society. You may work individually or in pairs, but you must each turn in your own detailed report. TO DO: Research the requirements to live for one month on a low income in our area. TO TURN IN: a. A list of necessary items for a household b. A detailed budget with complete information about how it will work (address, transportation plan, nutritious meal plan for one week, where you will shop, etc); you may include maps, hot links, etc to provide context for your choices and justify your budget decisions c. A conclusion that provides a reflection on what you discovered about living with a low income and how well you personally would manage under these conditions 5 NOTE: This assignment may be in outline form, PowerPoint, Excel or Word – your choice. Only the conclusion must be in paragraph form. Introduction: Generally speaking, many people think of the US as a more or less equal society, especially since we have never had a titled aristocracy and, with the exception of our racial history, this nation has never known a caste system that rigidly ranks categories of people. Quite often, in fact, we often see ourselves as a middle class society. Despite this, inequalities do exist. Inequality, however, does not necessarily mean that class is all that important. In fact, for many Americans, class is not seen as very important because most people believe that regardless of social class, everyone has about the same chance to get ahead in society. What really justifies the US stratification system is the idea of “equality of opportunity.” But what exactly do “stratification” and “equality of opportunity” look like in our society? What are the impacts of social inequality on the lives of contemporary Americans? We cannot begin to answer these questions without taking some initial steps. Let’s first take a look at the most basic collective within society: the household. This unit can be made up of as few as one person and as many as ten. 1. Make a list of important household budget items that a family needs in order to survive. Your list must include rent/mortgage, food, utilities, transportation, insurance, clothing, education and savings. Other things you might want to include are childcare, entertainment, pets, the list goes on. If you don’t know how much each of these items costs per week or month, find out! You may ask your parents or friends if you need help with this. 2. Do the research. For this exercise you are the head of household for a family of four. You have an adult partner and two young children, ages 3 and 7 (preschool and 1st or 2nd grade). You and your family have just moved to Seattle. You and your partner each have full time minimum wage jobs ($9.04/hr in Washington – more than in most states), but neither of you has a college degree. Using craigslist and other local resources put together a budget based on your income and the list you made of the important household budget items a family like yours would require. You may assume that you already have the basics of furniture and clothing for your family. 3. Come to class prepared to share your budget and explain how you have worked out your family’s needs in real-life examples (How much do you bring in each month? Where will you live? Where will you shop? Will you have a car? How will you plan nutritious meals on your food budget?). 4. Write it up. Create a detailed budget including complete information about how it will work plus a conclusion reflecting on what you discovered and how well you would survive. The conclusion must be at least one paragraph, but the rest may be in any format (outline, Excel, PowerPoint, Word). Are you able to survive on this income? If you find you could survive, is this sustainable? Can you get ahead? Can you move up to a higher socioeconomic status? If so, how? If you find you couldn’t survive, what does that mean for our society and our sense of American opportunity? 6