El 12 de enero

advertisement

El 12 de

enero

2016

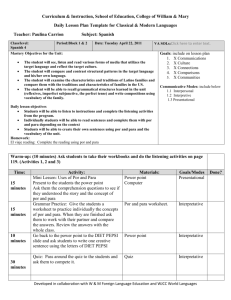

Español V

4

CAPÍTULO

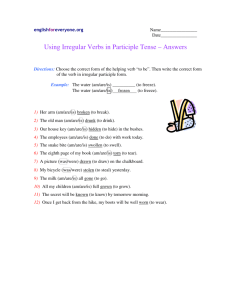

El PRESENTE PERFECTO

ACTIVIDADES

Hoy una actividad especial:

Un día especial con una presentación

de la cultura e historía de España¡

España

Página 155 Actividad 2 y 3

Página 157 Actividad 6

Página 163 Actividad 3

Página 164 Actividad 5

Página 168 Actividad 12

Página 171 Actividad 17

Lección de hoy

1.

2.

3.

4.

viernes

Por y para en repaso

El Presente Perfecto

Los Participios del pasado

Los participios del pasado –

Los irregulars

5. Realidades 3 página 214

Actividad 14.

5. Actividad 33 página 18

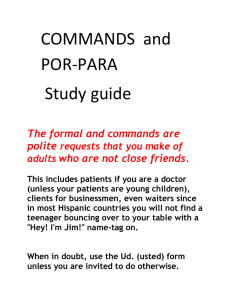

Nosotros commands

NOSOTROS commands are more frequently used to suggest that others

do some activity with you rather than to command: let's do something or

let's not do something. We already learned a way to say let's do something

by using VAMOS A + infinitive verb:

¡Vamos a caminar! Let's go to walk!

¡Vamos a comer! Let's go to eat!

¡Vamos a escribir! Let's go to write!

It is important to use exclamation marks to indicate that the construction

VAMOS A + Infinitive is used as a NOSOTROS command. Otherwise, it

can have another meaning (in the present tense and near future):

Nosotros vamos a caminar We go to walk or we will go to walk

Nosotros vamos a comer We go to eat or we will go to eat

Nosotros vamos a escribir We go to write or we will go to write

Now, we will learn how NOSOTROS command is formed by using the

NOSOTROS form of the present subjunctive.

*NOTICE THE COLOR CODE OF THE VERB ENDINGS:

-emos: NOSOTROS command of -AR verbs

-amos: NOSOTROS command of -ER and -IR verbs

COMMAND FORMS OF -AR VERBS

Drop the -ar ending of the infinitive form of the verb, and add -emos"''"

table tableId="table_d2e226" .table_d2e226 { border: 1px solid;

width: 80%; border-color: #ffffcc; } .table_d2e226 td { border: 1px

solid; border-color: #ffffcc; }

Infinitive verb

tomar (to take/drink)

trabajar (to work)

NOSOTROS command

tomemos

trabajemos

Examples:

Affirmative NOSOTROS

Estudiemos (Let's study)

Caminemos (Let's walk)"''"

Negative NOSOTROS

No estudiemos

No caminemos"''"

/area Type="main"

area Type="area_a" face="Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif" size="2"

color="black" style="0" password_protection="basic"

COMMAND FORMS OF -ER AND -IR VERBS

Drop the -er or -ir ending of the infinitive form of the verb, and add -amos"''"

table tableId="table_d2e13" .table_d2e13 { border: 1px solid;

width: 100%; border-color: #ffffcc; } .table_d2e13 td { border: 1px

solid; border-color: #ffffcc; }

Infinitive verb

comer

leer

escribir

recibir

NOSOTROS co

comamos

leamos

escribamos

recibamos

Examples:

Affirmative NOSOTROS

Comamos las frutas (let's eat the fruits)

Escribamos un poema (let's write a poem)"''"

Negative NOSO

No comamos la

No escribamos

/area Type="area_a"

area Type="area_b" face="Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif" size="2"

color="black" style="0" password_protection="basic"

NOSOTROS COMMAND OF VERBS ENDING IN -CAR, -GAR AND -ZAR

Verbs ending in -car, -gar, and -zar require spelling changes in order to

keep the pronunciation.

-CAR: C changes to QU

-GAR: G changes to GU

-ZAR: Z changes to C

"''"

table tableId="table_d2e31" .table_d2e31 { border: 1px solid;

width: 70%; border-color: #ffffcc; } .table_d2e31 td { border: 1px

solid; border-color: #ffffcc; }

Infinitive

Tocar (to touch/play)

Buscar (to look for)

Practicar (to practice)

Educar (to educate)

Llegar (to arrive)

Nosotros command

toquemos

busquemos

practiquemos

eduquemos

lleguemos

Jugar (to play)

Navegar (to navigate)

Pagar (to pay)

Comenzar (to start/begin)

Empezar (to start/to begin)

Cruzar (to cross)

Almorzar (to eat lunch)"''"

juguemos

naveguemos

paguemos

comencemos

empecemos

crucemos

almorcemos"''"

/area Type="area_b"

Diego ha sido mi amigo por veinte años.

Diego has been my friend for 20 years.

The present perfect tense is often used with the

adverb "ya".

Ya han comido.

They have already eaten.

La empleada ya ha limpiado la casa.

The maid has already cleaned the house.

The auxiliary verb and the past participle are never separated. To make the

sentence negative, add the word "no" before the conjugated form of haber.

(yo) No he comido.

I have not eaten.

(tú) No has comido.

You have not eaten.

(él) No ha comido.

He has not eaten.

(nosotros) No hemos comido.

We have not eaten.

(vosotros) No habéis comido.

You-all have not eaten.

(ellos) No han comido.

They have not eaten.

Again, the auxiliary verb and the past participle are never separated. Object

pronouns are placed immediately before the auxiliary verb.

Pablo le ha dado mucho dinero a su hermana.

Pablo has given a lot of money to his sister.

To make this sentence negative, the word "no" is placed before the indirect

object pronoun (le).

Pablo no le ha dado mucho dinero a su hermana.

Pablo has not given a lot of money to his sister.

With reflexive verbs, the reflexive

pronoun is placed immediatedly

before the auxiliary verb. Compare

how the present perfect differs from

the simple present, when a reflexive

verb is used.

Me cepillo los dientes. (present)

I brush my teeth.

Me he cepillado los dientes.

(present perfect)

I have brushed my teeth.

To make this sentence negative, the word "no" is placed before the reflexive

pronoun (me).

No me he cepillado los dientes.

I have not brushed my teeth.

For a review of reflexive verbs click [here] and [here].

Questions are formed as follows. Note how the word order is different than the

English equivalent.

¿Han salido ya las mujeres?

Have the women left yet?

¿Has probado el chocolate alguna vez?

Have you ever tried chocolate?

Here are the same sentences in negative form. Notice how the auxiliary verb and

the past participle are not separated.

¿No han salido ya las mujeres?

Haven't the women left yet?

¿No has probado el chocolate ninguna vez?

Haven't you ever tried chocolate?

Present Perfect

The Perfect Tenses

1 Introduction. The perfect tenses [tiempos perfectos] are

compound tenses [tiempos compuestos]; that is, they are

made up of two parts, a helping verb [verbo auxiliar] and a

past participle [participio pasado], for example: he hablado

(I have spoken), habías hablado (you had spoken),

habremos hablado (we will have spoken). There are three

main perfect tenses in the indicative: present perfect, past

perfect, and future perfect. They are “perfect” or “pefective”,

as opposed to “imperfect” or “imperfective”, in the sense that

they portray an action or state as completed and not in

progress, from the point of view of present, past, or future

time, respectively. The perfect tenses in Spanish are formed

with: The helping verb haber, in the appropriate tense and mood,

plus:

The masculine singular form of the past participle.

The present perfect is formed by combining the auxiliary verb "has" or "have"

with the past participle.

I have studied.

He has written a letter to María.

We have been stranded for six days.

Because the present perfect is a compound tense, two verbs are required: the

main verb and the auxiliary verb.

I have studied.

(main verb: studied ; auxiliary verb: have)

He has written a letter to María.

(main verb: written ; auxiliary verb: has)

We have been stranded for six days.

(main verb: been ; auxiliary verb: have)

In Spanish, the present perfect tense is formed by using the present tense of the

auxiliary verb "haber" with the past participle. Haber is conjugated as follows:

he

has

ha

hemos

habéis

han

You have already learned in a previous lesson that the past participle is formed

by dropping the infinitive ending and adding either -ado or -ido. Remember, some

past participles are irregular. The following examples all use the past participle

for the verb "comer."

(yo) He comido.

I have eaten.

(tú) Has comido.

You have eaten.

(él) Ha comido.

He has eaten.

(nosotros) Hemos comido.

We have eaten.

(vosotros) Habéis comido.

You-all have eaten.

(ellos) Han comido.

They have eaten.

For a review of the formation of the past participle [click here].

When you studied the past participle, you practiced using it as an adjective.

When used as an adjective, the past participle changes to agree with the noun it

modifies. However, when used in the perfect tenses, the past participle never

changes.

Past participle used as an adjective:

La cuenta está pagada.

The bill is paid.

Past participle used in the present perfect tense:

He pagado la cuenta.

I have paid the bill.

Here's a couple of more examples:

Past participle used as an adjective:

Las cuentas están pagadas.

The bills are paid.

Past participle used in the present perfect tense:

Juan ha pagado las cuentas.

Juan has paid the bills.

Note that when used to form the present perfect tense, only the base form

(pagado) is used.

Let's look more carefully at the last example:

Juan ha pagado las cuentas.

Juan has paid the bills.

Notice that we use "ha" to agree with "Juan". We do NOT use "han" to agree with

"cuentas." The auxiliary verb is conjugated for the subject of the sentence, not

the object. Compare these two examples:

Juan ha pagado las cuentas.

Juan has paid the bills.

Juan y María han viajado a España.

Juan and Maria have traveled to Spain.

In the first example, we use "ha" because the subject of the sentence is "Juan."

In the second example, we use "han" because the subject of the sentence is

"Juan y María."

The present perfect tense is frequently used for past actions that continue into

the present, or continue to affect the present.

He estado dos semanas en Madrid.

I have been in Madrid for two weeks.

Diego ha sido mi amigo por veinte años.

Diego has been my friend for 20 years.

The present perfect tense is often used with the adverb "ya".

Ya han comido.

They have already eaten.

La empleada ya ha limpiado la casa.

The maid has already cleaned the house.

The auxiliary verb and the past participle are never separated. To make the

sentence negative, add the word "no" before the conjugated form of haber.

(yo) No he comido.

I have not eaten.

(tú) No has comido.

You have not eaten.

(él) No ha comido.

He has not eaten.

(nosotros) No hemos comido.

We have not eaten.

(vosotros) No habéis comido.

You-all have not eaten.

(ellos) No han comido.

They have not eaten.

Again, the auxiliary verb and the past participle are never separated. Object

pronouns are placed immediately before the auxiliary verb.

Pablo le ha dado mucho dinero a su hermana.

Pablo has given a lot of money to his sister.

To make this sentence negative, the word "no" is placed before the indirect

object pronoun (le).

Pablo no le ha dado mucho dinero a su hermana.

Pablo has not given a lot of money to his sister.

With reflexive verbs, the reflexive pronoun is placed immediatedly before the

auxiliary verb. Compare how the present perfect differs from the simple present,

when a reflexive verb is used.

Me cepillo los dientes. (present)

I brush my teeth.

Me he cepillado los dientes. (present perfect)

I have brushed my teeth.

To make this sentence negative, the word "no" is placed before the reflexive

pronoun (me).

No me he cepillado los dientes.

I have not brushed my teeth.

For a review of reflexive verbs click [here] and [here].

Questions are formed as follows. Note how the word order is different than the

English equivalent.

¿Han salido ya las mujeres?

Have the women left yet?

¿Has probado el chocolate alguna vez?

Have you ever tried chocolate?

Here are the same sentences in negative form. Notice how the auxiliary verb and

the past participle are not separated.

¿No han salido ya las mujeres?

Haven't the women left yet?

¿No has probado el chocolate ninguna vez?

Haven't you ever tried chocolate?

Irregular present participoles

Past Participles

The past participle will be important in future lessons covering the perfect tenses.

To form the past participle, simply drop the infinitive ending (-ar, -er, -ir) and add ado (for -ar verbs) or -ido (for -er, -ir verbs).

hablar - ar + ado = hablado

comer - er + ido = comido

vivir - ir + ido = vivido

The following common verbs have

irregular past participles:

abrir (to open) - abierto (open)

cubrir (to cover) - cubierto (covered)

decir (to say) - dicho (said)

escribir (to write) - escrito (written)

freír (to fry) - frito (fried)

hacer (to do) - hecho (done)

morir (to die) - muerto (dead)

poner (to put) - puesto (put)

resolver (to resolve) - resuelto (resolved)

romper (to break) - roto (broken)

ver (to see) - visto (seen)

volver (to return) - vuelto (returned)

Note that compound verbs based on the irregular

verbs inherit the same irregularities. Here are a few

examples:

componer - compuesto

describir – descrito

devolver - devuelto

Most past participles can be used as

adjectives. Like other adjectives, they

agree in gender and number with the

nouns that they modify.

La puerta está cerrada.

The door is closed.

Las puertas están cerradas.

The doors are closed.

El restaurante está abierto.

The restaurant is open.

Los restaurantes están abiertos.

The restaurants are open.

The past participle can be combined

with the verb "ser" to express the

passive voice. Use this construction

when an action is being described,

and introduce the doer of the action

with the word "por."

La casa fue construida por los

carpinteros.

The house was built by the

carpenters.

La tienda es abierta todos los días

por el dueño.

The store is opened every day by the

owner.

Note that for -er and -ir verbs, if the stem ends in a vowel, a written accent will be

required.

creer - creído

oír - oído

Note: this rule does not apply, and no written accent is required for verbs ending

in -uir. (construir, seguir, influir, distinguir, etc.)

Let's add two more flashcards for the past participles, since they will later be

used for the perfect tenses:

Verb Flashcards

Complete List

Past Participle

Infinitive - ending + ado/ido

(hablado, comido, vivido)

Past Participle Irregulars

abrir (to open) - abierto (open)

cubrir (to cover) - cubierto (covered)

decir (to say) - dicho (said)

escribir (to write) - escrito (written)

freír (to fry) - frito (fried)

hacer (to do) - hecho (done)

morir (to die) - muerto (dead)

poner (to put) - puesto (put)

resolver (to resolve) - resuelto (resolved)

romper (to break) - roto (broken)

ver (to see) - visto (seen)

volver (to return) - vuelto (returned)

Using the Present

Perfect Tense

The Present Perfect Tense is used to refer to events that

happened in the past. Its use in Spanish can be tricky,

however, because its usage varies with region and it

sometimes is used in slightly different ways than it is in

English.

In Spanish, the present perfect tense is formed by the present

tense of haber followed by the past participle. (In English it's

the present tense of "to have" followed by the past participle.)

Here then are the forms in which the present perfect would

be stated. Pronouns are included here for clarity but generally

aren't necessary:

•

yo he + past participle (I have ...)

•

tú has + past participle (you have ...)

•

usted/él/ella ha + past participle (you have, he/she has

...)

•

nosotros/nosotras hemos + past participle (we have ...)

•

vosotros/vosotras habéis + past participle (you have ...)

•

ustedes/ellos/ellas han + past participle

•

(you have, they have ...)

El PLUSCUAMPERFECTO

The Past Perfect in Spanish

The past perfect is formed by

combining the auxiliary verb "had"

with the past participle.

I had studied.

He had written a letter to María.

We had been stranded for six days.

Because the past perfect is a compound tense, two verbs

are required: the main verb and the auxiliary verb.

I had studied.

(main verb: studied ; auxiliary verb: had)

He had written a letter to María.

(main verb: written ; auxiliary verb: had)

We had been stranded for six days.

(main verb: been ; auxiliary verb: had)

In Spanish, the past perfect tense is formed by using the

imperfect tense of the auxiliary verb "haber" with the past

participle. Haber is conjugated as follows:

HABER

había

habías

había

habíamos

habíais

habían

You have already learned in a previous lesson that the past

participle is formed by dropping the infinitive ending and

adding either -ado or -ido. Remember, some past participles

are irregular. The following examples all use the past

participle for the verb "vivir."

(yo) Había vivido.

I had lived.

(tú) Habías vivido.

You had lived.

(él) Había vivido.

He had lived.

(nosotros) Habíamos vivido.

We had lived.

(vosotros) Habíais vivido.

You-all had lived.

(ellos) Habían vivido.

They had lived.

.

When you studied the past participle, you practiced using it

as an adjective. When used as an adjective, the past

participle changes to agree with the noun it modifies.

However, when used in the perfect tenses, the past

participle never changes.

Past participle used as an adjective:

La puerta está cerrada.

The door is closed.

Past participle used in the past perfect tense:

Yo había cerrado la puerta.

I had closed the door.

Here's a couple of more examples:

Past participle used as an adjective:

Las puertas están abiertas..

The doors are open.

Past participle used in the past perfect tense:

Juan había abierto las puertas.

Juan had opened the doors.

Note that when used to form the perfect tenses, only the

base form (abierto) is used.

The last example:

Juan había abierto las puertas.

Juan had opened the doors.

Notice that we use "había" to agree with "Juan". We do NOT

use "habían" to agree with "puertas." The auxiliary verb is

conjugated for the subject of the sentence, not the object.

Compare these two examples:

Juan había abierto las puertas.

Juan had opened the doors.

Juan y María habían puesto mucho dinero en el banco.

Juan and Maria had put a lot of money in the bank.

In the first example, we use "había" because the subject of

the sentence is "Juan." In the second example, we use

"habían" because the subject of the sentence is "Juan y

María."

The past perfect tense is used when a past action was

completed prior to another past action. Expressions such as

"ya", "antes", "nunca", "todavía" and "después" will often

appear in sentences where one action was completed before

another.

Cuando llegaron los padres, los niños ya habían

comido.

When the parents arrived, the children had already eaten.

Yo había comido antes de llamarles.

I had eaten prior to calling them.

This idea of a past action being completed before another

past action need not always be stated; it can be implied.

Juan había cerrado la ventana antes de salir. (stated)

Juan had closed the window before leaving.

Juan había cerrado la ventana. (implied)

Juan had closed the window.

The auxiliary verb and the past participle are never

separated.

To make the sentence negative, add the word "no" before

the conjugated form of haber.

(yo) No había vivido.

I had not lived.

(tú) No habías vivido.

You had not lived.

(él) No había vivido.

He had not lived.

(nosotros) No habíamos vivido.

We had not lived.

(vosotros) No habíais vivido.

You-all had not lived.

(ellos) No habían vivido.

They had not lived.

Again, the auxiliary verb and the past participle are never

separated. Object pronouns are placed immediately before

the auxiliary verb.

Pablo le había dado mucho dinero a su hermana.

Pablo had given a lot of money to his sister.

To make this sentence negative, the word "no" is placed

before the indirect object pronoun (le).

Pablo no le había dado mucho dinero a su hermana.

Pablo had not given a lot of money to his sister.

With reflexive verbs, the reflexive pronoun is placed

immediatedly before the auxiliary verb. Compare how the

present perfect differs from the simple present, when a

reflexive verb is used.

Me lavo las manos. (present)

I wash my hands.

Me había lavado las manos. (past perfect)

I had washed my hands.

To make this sentence negative, the word "no" is placed

before the reflexive pronoun (me).

No me había lavado las manos.

I had not washed my hands.

For a review of reflexive verbs click [here] and [here].

Questions are formed as follows. Note how the word order is

different than the English equivalent.

¿Habían llegado ya las chicas?

Had the girls arrived yet?

¿Habías probado ya el postre?

Had you tried the dessert yet?

Here are the same questions in negative form. Notice how

the auxiliary verb and the past participle are not separated.

¿No habían llegado ya las chicas?

Hadn't the girls arrived yet?

¿No habías probado ya el postre?

Hadn't you tried the dessert yet?

MORE ON THE:

El PLUSCUAMPERFECTO

We use the pretérito pluscuamperfecto (past

perfect) to describe actions that took place

before a certain point in the past.

We always use the past perfect when we are

telling a story (in the simple past) and then want

to look back at something that happened earlier.

En una competición de

talentos, Luisa tocó una pieza

de música muy complicada

con su flauta.

Había practicado mucho para

presentar esta pieza tan

perfectamente.

Usage

action before a certain point in the pastExample:

Había practicado mucho para

presentar esta pieza tan perfectamente.

Construction

We need the past forms (pretérito imperfecto) of

the helping verb haber, and the perfect participle

(participio pasado).

person

yo

tú

él/ella/usted

nosotros/-as

vosotros/-as

ellos/ellas/ustedes

Perfect participle

haber

había

habías

había

habíamos

habíais

habían

perfect participle

hablado

aprendido

vivido

We construct the perfect participle by removing the infinitive

ending, and then adding the ending ado to ar-verbs and the

ending ido to er/ir-verbs.

Example:

hablar – hablado

aprender – aprendido

vivir – vivido

Exceptions in the perfect participle

• If there is a vowel before the ido-ending, we have to add an

accent on the i of the ending. This shows us that each

vowel is pronounced separately (not a

diphthong).

Example:

leer – leído

traer – traído

• Some verbs have an irregular and/or regular participle

form. These can be found in the following list:

verb

abrir

decir

escribir

perfect participle

irregular

abierto

dicho

escrito

translation

regular

open

say

write

hacer

freír

imprimir

morir

poner

proveer

suscribir

ver

volver

hecho

frito

impreso

muerto

puesto

provisto

suscrito/suscripto

visto

vuelto

freído

imprimido

proveído

do/make

fry

print

die

place/set

provide

sign/subscribe

see

return

cooking project below……

COOKING PROJECT

BELOW!!!

La Presentacíon de la comida

El Día de Presentar y Comer

Cooking and Culture

Project

Il Proyecto Grande

Chef of the Future¡▶ 10:51

PROJECT INFORMATION I

THE RESEARCH

La Comida

1. Select a Food of a particular city

and region of Spain or LatinAmerican countrya. Ingredients in Spanish

With drawings or fotos

5 pts.

b. LA RECETA recipe 5 pts.

with FOTOS/PICTURES

c. WHEN DO PEOPLE EAT

THIS? DESCRIBE IN

DETAIL

5 pts

Presentation in Spanish

20pts.

Al traer la comida/dessert

20

55 puntos

Presenaciones : el 18 de diciembre

2015

La presentación

II THE CITY (AND REGION)

MAKE A MAP OF Spain and region

or make a Map of your selected

country from Latina America

(no print outs) 5 pts

A. FIVE MAJOR places of

interest describe

With fotos and

explanation

25pts

B. CELEBRATIONSDescribe at least ONE

major cultural festival

in your city fotos and a

description (escrito)

10 pts

C. MUSIC, DANCE,

Art : 5 pts

45 puntos para este

parte

La presentación de la culture

(ciudad)

es el 18 de diciembre

LA COMIDA- il 22 de diciembre

1015

Realidades 3

CAPíTULO 4

Search Results

m

Friends

Tarjetas para amigos

El subjuntivo con verbos de emoción

The form for the Subjunctive and Emotion is the

required 3-part formula.

We can express opinions about things that we observe or

consider fact.

For example, if we know that Juan sings well, we say "Juan

canta bien." We can even say we believe that Juan sings

well, "creemos que Juan canta bien."

But when we want to express how we FEEL

about Juan's singing, we need to use the

Subjunctive.

For example, to say we are pleased that Juan sings well,

we say:

Nos gusta que Juan cante bien.

"Cante" is the 3rd person subjunctive form of Cantar.

It seems funny to have to use the Subjunctive with

something that seems factual; but really what is being

expressed is your personal reaction.

The focus isn't on any statement of fact - rather on your

value judgement of an event or situation. Since your

emotional response is subjective, we need to use the

Subjunctive.

I am happy that you are

going to Spain!

I'm sorry that he has to

study tonight.

He is afraid that she

wants to break up with

him.

We hope the professor

won't give many exams.

Emotions

¡Me alegro de que tú vayas

a España!

Siento que él tenga que

estudiar esta noche.

Tiene miedo que ella

quiera romper con él.

Esperamos que la

profesora no dé muchos

exámenes.

Being annoyed, angry, happy, regretful, sad, scared, or surprised all fall

into this category. Any personal reaction to a situation is emotional. The

focus is not on a factual observation of a situation but how it makes the

subject feel. Since how a person feels is always subjective, you use the

subjunctive.

2 Me alegro de que sonrías. (It makes me happy that you smile.)

3 ¿Les molesta que él escuche la música fuerte? (Does it bother

you that he listens to loud music?)

4 Siento mucho que no puedan venir a la fiesta. (I’m sorry that

they can’t come to the party.)

Useful Verbs of Emotion

alegrarse

de *

encantar

enojar

estar

to be glad

to be

delighted

to be

angry

gustar

to like

quejarse

to compla

lamentar

to regret

sentir

to feel

maravillar

to astonish

sorprender

to surprise

to annoy

temer

to fear

to be glad, molestar

contento,

angry, sad,

enojado,

etc.

triste, etc.

tener

miedo

de/a que

to be

extrañarse

to be

afraid that

que

amazed that

*This verb occasionally carries the subjunctive in its subordinate

clause (more frequently in America than in Spain).

When this occurs the focus changes slightly from that of

affectation to that of assertion (i.e. the use of the indicative reveals the

speakers intention to highlight the informational content of the

subordinate).

"Por" and "Para"

"Por" and "para" have a variety of meanings, and they are often confused

because they can each be translated as "for."

Gracias por la información.

Thanks for the information.

Este regalo es para Juan.

This gift is for Juan.

To learn to use "por" and "para" correctly, you need to do two things:

• Learn the rules for how por and para are used.

• Memorize model sentences.

"Por" has many uses, and so it is the more problematic of the two.

Rule: to express gratitude or apology

Model: Gracias por la ayuda.

(Thanks for the help.)

Rule: for multiplication and division

Model: Dos por dos son cuatro.

(Two times two equals four.)

Rule: for velocity, frequency and proportion

Model: Voy al restaurante cinco veces por semana.

(I go to the restaurant five times per week.)

Rule: meaning "through," "along," "by" or "in the area of"

Model: Andamos por el parque.

(We walk through the park.)

Rule: when talking about exchange, including sales

Model: Él me dio diez dólares por el libro.

(He gave me ten dollars for the book.)

Rule: to mean "on behalf of," or "in favor of,"

Model: No voté por nadie.

(I didn't vote for anyone.)

Rule: to express a length of time

Model: Yo estudié por dos horas.

(I studied for two hours.)

Rule: to express an undetermined, or general time, meaning "during"

Model: Se puede ver las estrellas por la noche

.

(One can see the stars during the night.)

Rule: for means of communication or transportation

Model: Prefiero viajar por tren y hablar por teléfono.

(I prefer to travel by train and speak by phone.)

Rule: in cases of mistaken identity, or meaning "to be seen as"

Model: Me tienen por loco.

(They take me for crazy.)

Rule: to show the reason for an errand (with ir, venir, pasar, mandar, volver, and

preguntar)

Model: Paso por ti a las ocho.

(I'll come by for you at eight o'clock.)

Rule: when followed by an infinitive, to express an action that remains to be

completed, use por + infinitive

Model: La cena está por cocinar.

(Dinner has yet to be cooked.)

Rule: to express cause or reason

Model: El hombre murió por falta de agua.

The man died for lack of water.

Rule: "estar por" means to

be in the mood, or inclined

to do something

Model: Estoy por tomar café.

(I'm in the mood for drinking coffee.)

Rule: in passive constructions

Model: El libro fue escrito por Octavio Paz.

(The book was written by Octavio Paz.)

"Por" also appears in many

idiomatic expressions:

por adelantado

in advance

por ahora

for now

por allí

around there; that way

por amor de Dios

for the love of God

por aquí

around here; this way

por casualidad

by chance

por ciento

percent

por cierto

certainly

por completo

completely

por dentro

inside

por desgracia

unfortunately

por ejemplo

for example

por eso

therefore

por favor

please

por fin

finally

por lo general

generally

por lo visto

apparently

por medio de

by means of

por lo menos

at least

por lo tanto

consequently

por mi parte

as for me

por ningún lado

nowhere

por otra parte

on the other hand

palabra por palabra

word for word

por primera vez

for the first time

por separado

separately

por supuesto

of course

por suerte

fortunately

por todas partes

everywhere

por todos lados

on all sides

por último

finally

"Para" -- in contrast, has

relatively fewer uses.

Rule: to indicate destination

Model: El hombre salió para Madrid.

(The man left for Madrid.)

Rule: to show the use or purpose of a thing

Model: El vaso es para agua.

(The glass is for water.)

Rule: to mean "in order to" or "for the purpose of"

Model: Para hacer una paella, primero dore las carnes.

To make a paella, first sauté the meats.

Rule: to indicate a recipient

Model: Este regalo es para ti.

(This gift is for you.)

Rule: to express a deadline or specific time

Model: Necesito el vestido para el lunes.

(I need the dress by Monday.)

Rule: to express a contrast from what is expected

Model: Para un niño lee muy bien.

(For a child, he reads very well.)

Rule: "estar para" to express an action that will soon be completed

Model: El tren está para salir.

(The train is about to leave.)

WARNING¡ WARNING ¡ WARNING¡

¡CUIDADO!

¡CUIDADO!

¡CUIDADO!

¡CUIDADO!

"Por" and "Para"

"Por" and "para" have a variety of

meanings, and they are often confused

because they can each be translated as

"for."

Gracias por la información.

Thanks for the information.

Este regalo es para Juan.

This gift is for Juan.

To learn to use "por" and "para" correctly,

you need to do two things:

Learn the rules for how por and para are

used.

Memorize model sentences.

"Por" has many uses, and so it is the more problematic of the two.

Rule: to express gratitude or apology

Model: Gracias por la ayuda.

(Thanks for the help.)

Rule: for multiplication and division

Model: Dos por dos son cuatro.

(Two times two equals four.)

Rule: for velocity, frequency and proportion

Model: Voy al restaurante cinco veces por semana.

(I go to the restaurant five times per week.)

Rule: meaning "through," "along," "by" or "in the area of"

Model: Andamos por el parque.

(We walk through the park.)

Rule: when talking about exchange, including sales

Model: Él me dio diez dólares por el libro.

(He gave me ten dollars for the book.)

Rule: to mean "on behalf of," or "in favor of,"

Model: No voté por nadie.

(I didn't vote for anyone.)

Rule: to express a length of time

Model: Yo estudié por dos horas.

(I studied for two hours.)

Rule: to express an undetermined, or general time, meaning "during"

Model: Se puede ver las estrellas por la noche.

(One can see the stars during the night.)

Rule: for means of communication or transportation

Model: Prefiero viajar por tren y hablar por teléfono.

(I prefer to travel by train and speak by phone.)

Rule: in cases of mistaken identity, or meaning "to be seen as"

Model: Me tienen por loco.

(They take me for crazy.)

Rule: to show the reason for an errand (with ir, venir, pasar, mandar, volver, and

preguntar)

Model: Paso por ti a las ocho.

(I'll come by for you at eight o'clock.)

Rule: when followed by an infinitive, to express an action that remains to be

completed, use por + infinitive

Model: La cena está por cocinar.

(Dinner has yet to be cooked.)

Rule: to express cause or reason

Model: El hombre murió por falta de agua.

The man died for lack of water.

Rule: "estar por" means to be in the mood, or inclined to do something

Model: Estoy por tomar café.

(I'm in the mood for drinking coffee.)

Rule: in passive constructions

Model: El libro fue escrito por Octavio Paz.

(The book was written by Octavio Paz.)

"Por" also appears in many idiomatic

expressions:

por adelantado

in advance

por ahora

for now

por allí

around there; that way

por amor de Dios

for the love of God

por aquí

around here; this way

por casualidad

by chance

por ciento

percent

por cierto

certainly

por completo

completely

por dentro

inside

por desgracia

unfortunately

por ejemplo

for example

por eso

therefore

por favor

please

por fin

finally

por lo general

generally

por lo visto

apparently

por medio de

by means of

por lo menos

at least

por lo tanto

consequently

por mi parte

as for me

por ningú

n lado

nowhere

por otra parte

on the other hand

palabra por palabra

word for word

por primera vez

for the first time

por separado

separately

por supuesto

of course

por suerte

fortunately

por todas partes

everywhere

por todos lados

on all sides

por último

finally

"Para" -- in contrast, has relatively

fewer uses.

Rule: to indicate destination

Model: El hombre salió para Madrid.

(The man left for Madrid.)

Rule: to show the use or purpose of a thing

Model: El vaso es para agua.

(The glass is for water.)

Rule: to mean "in order to" or "for the purpose of"

Model: Para hacer una paella, primero dore las carnes.

To make a paella, first sauté the meats.

Rule: to indicate a recipient

Model: Este regalo es para ti.

(This gift is for you.)

Rule: to express a deadline or specific time

Model: Necesito el vestido para el lunes.

(I need the dress by Monday.)

Rule: to express a contrast from what is expected

Model: Para un niño lee muy bien.

(For a child, he reads very well.)

Rule: "estar para" to express an action that will soon be completed

Model: El tren está para salir.

(The train is about to leave.)

It is quite important to learn to use

these two prepositions correctly,

because if you inadvertently

substitute one for the other, you

might end up saying something

altogether different from what you

had intended. Study the two

examples:

Juan compró el regalo para María.

Juan bought the gift for Maria.

(he bought it to give to her)

Juan compró el regalo por María.

Juan bought the gift for Maria.

(he bought it because she could not)

"Por" and "para" can also be used in questions. "¿Por qué?" means "Why?" (for

what reason) while "¿Para qué?" means "Why?" (for what purpose).

¿Por qué estudias español?

For what reason do you study Spanish?

Possible answer:

Porque es un requisito.

Because it's required.

¿Para qué estudias español?

For what purpose do you study Spanish?

Possible answer:

Para ser profesor de español.

In order to become a Spanish teacher.

It is quite important to learn to use these

two prepositions correctly, because if

you inadvertently substitute one for the

other, you might end up saying

something altogether different from what

you had intended. Study the two examples:

Juan compró el regalo para María.

Juan bought the gift for Maria.

(he bought it to give to her)

Juan compró el regalo por María.

Juan bought the gift for Maria.

(he bought it because she could not)

"Por" and "para" can also be used in questions. "¿Por qué?" means "Why?" (for

what reason) while "¿Para qué?" means "Why?" (for what purpose).

¿Por qué estudias español?

For what reason do you study Spanish?

Possible answer:

Porque es un requisito.

Because it's required.

¿Para qué estudias español?

For what purpose do you study Spanish?

Possible answer:

Para ser profesor de español.

In order to become a Spanish teacher.