Inventories

Revsine/Collins/Johnson/Mittelstaedt/Soffer: Chapter 9

Copyright © 2015 McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. No reproduction or distribution

without the prior written consent of McGraw-Hill Education

Learning objectives

1. The relationship between inventory valuation and cost of goods sold.

2. The two methods used to determine inventory quantities—perpetual

and periodic.

3. What types of costs are included in inventory.

4. What absorption costing is and how it complicates financial analysis.

5. The difference between inventory cost flow assumptions—weighted

average, FIFO and LIFO.

6. How LIFO reserve disclosures can be used to estimate inventory

holding gains and to transform LIFO firms to a FIFO basis.

9-2

Learning objectives concluded

7. How LIFO liquidation distorts cost of goods sold.

8. How LIFO affects firms’ income taxes.

9. Economic incentives guiding the choice of inventory methods.

10. How to apply the lower of cost or market method.

11. The key differences between GAAP and IFRS requirements for

inventory accounting.

12. How to eliminate realized holding gains from FIFO income.

13. How and why the dollar-value LIFO method is applied.

9-3

Inventory types

Wholesaler or retailer:

Manufacturer:

Supplier

Manufacturer

Firm

Raw materials

Firm

Merchandise

inventory

Work-in-process

Includes other

manufacturing

costs

Finished goods

Customer

Customer

9-4

Overview of accounting issues

Old unit

New unit

Issue: What costs are

included in inventory?

Issue: How is the cost of

goods available for

sale split between the

balance sheet and the

income statement?

9-5

Overview of accounting issues:

Summary

Three methods for allocating the

cost of goods available for sale:

Weighted average

FIFO

LIFO

GAAP does not require the cost

flow assumption to correspond to

the actual physical flow of

inventory.

If the cost of inventory never

changes, all three cost flow

assumptions would yield the same

financial statement result.

No matter what assumption is

used, the total dollar amount

assigned to the balance sheet and

the income statement is the same

($640 in this example).

9-6

Overview of accounting issues:

Allocating the cost of goods available for sale

Weighted average approach:

Uses the

the average

average cost

cost of

of the

the two

two

Uses

units.

units.

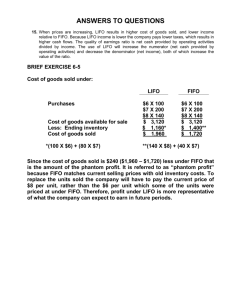

FIFO

produces

a smaller

expense

First-in, first-out (FIFO) approach:

Oldest unit cost flows to income.

Last-in, last-out (LIFO) approach:

LIFO

produces

a larger

expense

Newest unit cost flows to income.

9-7

Overview of accounting issues:

Unanswered questions

How should physical quantities in inventory be determined?

What items should be included in ending inventory?

What costs should be included in inventory purchases (and

eventually in ending inventory)?

What cost flow assumption should be used for allocating goods

available for sale between cost of goods sold and ending

inventory?

9-8

Determining inventory quantities:

Perpetual inventory system

This approach keeps a running (or “perpetual”) record of the

amount of inventory on hand.

The inventory T-account under a perpetual inventory system

looks like this:

Entries are made as

units are purchased

Entries are made as

units are sold

9-9

Determining inventory quantities:

Periodic inventory system

This approach does not keep a running (or “perpetual”) record of

the amount of inventory on hand.

Entries are made as units are purchased

Ending inventory and cost of goods sold must be determined by

physically counting the goods on hand at the end of the period.

9-10

Determining inventory quantities:

Periodic and perpetual compared

9-11

Determining inventory quantities:

Periodic and perpetual compared

Periodic inventory

Perpetual inventory

Less recordkeeping means lower

cost to maintain.

More complicated and usually more

expensive.

Less management control over

inventory.

Does not eliminate the need to take

a physical inventory.

COGS is a “plug” figure and there is

no way to determine the extent of

inventory losses (“shrinkage”).

Better management control over

inventories including “stock outs”.

Typically used for low volume, high

unit cost items (e.g., automobiles)

or when continuous monitoring of

inventory levels is essential.

Typically used when inventory

volumes are high and per-unit costs

are low.

9-12

Items included in inventory

In day-to-day operations, most firms record inventory when they

physically receive it.

However, when it comes to preparing financial statements, the

firm must determine whether all inventory items are legally owned.

Goods in transit may be “owned” by the buyer or the seller.

The party that has legal title during transit will record the items as

inventory.

Consignment goods should not be counted as inventory for the

consignee.

Consignor

Owner

consigned

goods

Consignee

Sale

Customer

Agent

9-13

Costs included in inventory

All costs required to obtain physical possession of the inventory

and to make it saleable.

Purchase cost

Sales taxes and transportation paid by the buyer

Insurance costs

Storage costs

Production costs (labor and overhead) for a manufacturer

In theory, inventory costs should also include the (indirect) costs

of the purchasing department and other general and

administrative costs associated with the acquisition and

distribution of inventory.

However, most firms exclude these items and limit inventory costs

to direct acquisition and processing costs.

9-14

Costs included in inventory:

Manufacturing costs

9-15

Costs included in inventory:

Absorption costing versus variable costing

Fixed

production

costs

Manufacturing rentals

and depreciation

Property taxes

Variable

production

costs

Variable

production

costs

Raw materials

Direct labor

Variable overhead, like

electricity

Variable costing of

inventory (not

allowed by GAAP)

Absorption costing

of inventory

(required by GAAP)

9-16

Costs included in inventory:

Summary

This approach is not

allowed by GAAP.

These are never

included in inventory.

9-17

Costs included in inventory:

How absorption costing can distort profitability

As we shall see, the GAAP gross margin increases from $110,000 in

2014 to $130,000 in 2015 even though variable production costs and

selling price are constant, and sales revenue has fallen.

9-18

Costs included in inventory:

Absorption costing distortion

9-19

Costs included in inventory:

Variable costing illustration

Under variable costing the gross margin falls

9-20

Cost flow assumptions:

The concepts

In a few industries, it is possible to identify which particular units

have been sold. Examples include jewelry stores and automobile

dealerships. These firms use specific identification inventory

costing.

For most firms, however, a cost flow assumption is required.

9-21

Cost flow assumptions:

First-in, First-out (FIFO) illustrated

FIFO

9-22

Cost flow assumptions:

First-in, First-out (FIFO) illustrated

Figure 9.1 FIFO Cost Flow

9-23

Cost flow assumptions:

Last-in, First-out (LIFO) illustrated

LIFO

9-24

Cost flow assumptions:

Last-in, First-out (LIFO) illustrated

Figure 9.2 LIFO Cost Flow

9-25

Cost flow assumptions:

Inventory holding gains summary

Figure 9.3

Holding gain

flows to income

Holding gain still

on balance sheet

9-26

Cost flow assumptions:

LIFO and inventory holding gains

Holding gain remains

on balance sheet

Usually (but not always) the same; however balance sheets

are very different.

9-27

Cost flow assumptions:

FIFO and inventory holding gains

FIFO automatically includes the holding gain on units that are sold.

9-28

Cost flow assumptions:

The LIFO reserve disclosure

Amount

shown on

balance sheet

if FIFO had

been used

Amount

actually

shown on

balance sheet

9-29

LIFO and inflation:

LIFO reserve

Figure 9.4 Magnitude of

Inventory and LIFO Reserve

relative to CPI and Oil Prices

9-30

LIFO liquidation

When a LIFO firm liquidates old LIFO layers, the net income

number under LIFO can be seriously distorted.

Current

purchases

45 units at $600 each

3rd layer

30 units at $500 each

2rd layer

20 units at $400 each

1st layer

10 units at $300 each

45 units at $600 each

80 units

30 units at $500 each

were sold

5 units at $400 each

How old

LIFO cost

distorts

COGS

LIFO cost of goods sold

Goods available

Old LIFO layers that are liquidated are “matched” against sales

dollars that are stated at higher current prices.

9-31

LIFO liquidation disclosures

Income tax effect ($910,000) was the difference.

9-32

Tax implications of LIFO

U.S. tax rules specify that

if LIFO is used for tax

purposes, LIFO must also

be used in external

financial statements.

This LIFO conformity rule

explains why so many

firms use LIFO for financial

reporting purposes.

9-33

Eliminating realized holding gains

for FIFO firms

Reported income for FIFO firms always includes some realized

holding gains during periods of rising inventory costs.

The size of the FIFO realized holding gain depends on:

How fast input costs are changing.

How fast inventory turns over during the period.

x 10% cost increase

Replacement COGS = 7,900,000

= 8,000,000

+

100,000

Realized FIFO

holding gain

9-34

Reasons why some companies do

not use LIFO

The estimated tax savings is too small.

Business cycles may cause extreme fluctuations in physical

inventory levels.

The rate of inventory obsolescence is high.

Managers may want to avoid reporting lower profits because they

believe doing so will lead to:

Lower stock price

Lower compensation from earnings-based bonuses

Loan covenant violations

Small firms may not find LIFO economical because of high recordkeeping costs.

9-35

Lower of Cost or Market Method

If the market value of inventory falls below its cost, the carrying value

must be reduced. Market value is subject to two constraints:

Ceiling – Net Realizable Value

Floor – Net Realizable Value less normal profit margin

Figure 9.5

Ceiling

Floor

9-36

Lower of Cost or Market Method

The journal entry when inventory with a cost of $1,000,000 is

written down to a market value of $970,000 would be (assuming

the use of the perpetual inventory method):

The lower of cost or market method can be applied to:

• Individual inventory items

• Classes of inventory

• The inventory as a whole

9-37

Global Vantage Point

Comparison of IFRS and GAAP Inventory

Accounting

IFRS guidelines for inventory are similar to U.S. GAAP

Two important differences

LIFO is not permitted under IAS 2

Lower of cost or market is applied differently. Market is net realisable

value (no ceiling or floor). IAS 2 allows inventory reductions to be

reversed if the market recovers, but the inventory carrying amount

cannot exceed the original cost.

Something to consider: LIFO conformity rule. Firms would incur

large tax liabilities if they eventually move to IFRS which does not

allow LIFO.

9-38

Summary

Absorption costing is required by GAAP but can lead to potentially

misleading trend comparisons.

GAAP allows firms latitude in selecting a cost flow assumption.

Some firms use FIFO, others use LIFO, and still others use

weighted-average.

This diversity can hinder comparisons across firms, thus it’s often

useful to convert LIFO firms to a FIFO basis.

Reported FIFO income includes potentially unsustainable realized

holding gains.

Similarly, LIFO liquidations distort reported margins.

Old, out-of-date LIFO layers can distort various ratio comparisons.

9-39

Summary concluded

Users must understand these inventory accounting differences

and know how to adjust for them. Only then can valid

comparisons be made across firms and over time.

To address inventory obsolescence, GAAP requires inventory to

be carried at lower of cost or market (LCM).

IFRS accounting for inventory is very similar to GAAP, but LIFO is

not allowed.

The LIFO conformity rules requires firms to use LIFO for financial

reporting if they use it for tax reporting.

Most LIFO firms use some form of dollar-value LIFO.

9-40