Urinary tract infection in children

advertisement

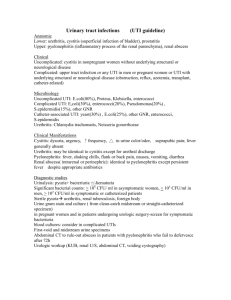

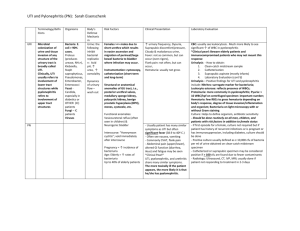

Urinary tract infection in children Professor Abdelaziz Elamin University of Khartoum Sudan Introduction • Urinary tract infections (UTI) is common in the pediatric age group. Early recognition and prompt treatment of UTI are important to prevent progression of infection to pyelonephritis or urosepsis and to avoid late sequelae such as renal scarring or renal failure. • Infants and young children with UTI may present with few specific symptoms. Older pediatric patients are more likely to have symptoms and findings attributable to an infection of the urinary tract. Differentiating cystitis from pyelonephritis in the pediatric patient is not always possible, although children who appear ill or who present with fever should be presumed to have pyelonephritis if they have evidence of UTI. Pathophysiology • UTI generally begins in the bladder due to ascending infection from perineal contaminants, usually bowel flora such as Escherichia coli. In neonates, infection of the urinary tract is assumed to be due to hematogenous rather than ascending infection. This etiology may explain the nonspecific symptoms associated with UTI in these patients. • After the neonatal period, bacteremia is not the usual cause of UTI. The bladder is the initial primary locus of infection with ascending disease to the kidneys. Bacteremia may then appear as potential sequelae. Bacterial invasion of the bladder with overt UTI is more likely to occur if urinary stasis or low flow conditions exist. This is triggered by infrequent or incomplete voiding, reflux, or other urinary tract abnormalities. Pathophysiology/2 •Even in the absence of urinary tract abnormalities, cystitis may lead to vesicoureteral reflux, and it may worsen a pre-existing reflux. Untreated reflux causes pyelonephritis. Chronic or recurrent pyelonephritis results in renal damage and scarring that may progress to chronic renal failure. •Prevalence varies based on age and sex Clinical Course • Generalized bacteremia or sepsis may follow UTI. Approximately 30% of 1- to 3-month-old infants with UTI are at risk of developing sepsis. The risk drops to approximately 5% in patients older than 3 months. • If left untreated, simple cystitis may progress to pyelonephritis. More severe cases have the potential for kidney damage, which may lead to hypertension or renal insufficiency. • Approximately 5-10% of children with symptomatic UTI and fever develop renal scarring. Frequency of UTI • UTI is more frequent in females than males at all ages with the exception of the neonatal period, during which UTI may be the cause of an overwhelming septic syndrome in male infants younger than 2 months. • Uncircumcised males have a higher incidence than circumcised males. Uncircumcised male infants have a higher incidence of UTI than female infants. Frequency of UTI/2 • Excluding neonates, females younger than 11 years have a 3-5% risk; boys of the same age have a 1% risk. • UTI is the source of infection in up to 6-8% of febrile infants in the first 3 months of life. Risk Factors 1. 2. • • • Bacterial virulence i.e. antigen K and presence of fimbriae Host factors : Anatomical VUR 35% of children with UTI –abnormal insertion of ureters in the bladder. Urinary tract obstruction caused by phimosis, meatal stenosis posterior urethral valves, diverticuli, and ureteric stricture or kink, and calculi. Indwelling catheter Functional : such as neurogenic bladder in spina bifida patients, and inappropriate detrusor muscle contractions Immunologic ; in immune deficiency Symptoms History: vary with the age of the patient. History is dependent upon the caregiver in younger children. Symptoms in Neonates: • Jaundice • Hypothermia or fever • Failure to thrive • Poor feeding • Vomiting Symptoms in Infants: • Poor feeding • Fever • Vomiting, diarrhea • Strong-smelling urine Symptoms/2 Preschoolers • Vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain • Fever • Strong-smelling urine, enuresis, dysuria, urgency, frequency School-aged children • Fever • Vomiting, abdominal pain • Strong-smelling urine, frequency, urgency, dysuria, flank pain, or new enuresis Adolescents are more likely to have some of the classic adult symptoms. Adolescent girls are more likely to have vaginitis (35%) than UTI (17%). Those diagnosed with cystitis frequently have a concurrent vaginitis. Physical Examination • Hypertension should raise suspicion of hydronephrosis or renal parenchyma disease. • Costovertebral angle (CVA) tenderness • Abdominal tenderness or mass • Palpable bladder • Dribbling, poor stream, or straining to void • Examine external genitalia for signs of irritation, pinworms, vaginitis, trauma, sexual abuse, phimosis or meatal stenosis . Etiology • Bacterial infections are the most common. • E coli is the most common causing 75-90% of UTI episodes. Other bacteria include: • Klebsiella species • Proteus species • Enterococcus species • Staphylococcus saprophyticus • Adenovirus (rare) • Fungal in immune compromised patients Differential Diagnoses The symptoms of UTI may mimic other conditions like: • Sepsis due to bacterimia or viremia • Falciparum malaria • Gastro-intestinal disorders • Renal Calculi with or without obstruction • Urethritis • Vaginitis & Vulvovaginitis Investigations • Lab Studies: • Urinalysis: A urine specimen that is found to be positive for nitrite, leukocyte esterase, or blood may indicate a UTI. • Microscopic examination can evaluate presence of WBCs (>5 per high-power field), RBCs, bacteria, casts, and skin contamination (e.g., epithelial cells). • A midstream clean catch is appropriate if the patient is old enough to cooperate. Clean skin around the urethral meatus and allow first urine to go into the toilet; then, collect the specimen in a sterile collection cup. • In neonates & infants sample obtained by bladder puncture is the best, but a bag specimen may be used if the urine bag is removed immediately after urine is deposited. It is adequate for specific gravity and chemical parameters but not for culture. Investigations/2 • Urine cultures should be sent to the laboratory even if urinalysis results are inconclusive. Approximately 20% of pediatric patients with UTI have normal urinalyses results. • Results are best interpreted with knowledge of the collection method and results of the urinalysis. • A clean-catch urine sample with more than 100,000 colony-forming units (CFU) of a single organism is classic criteria for UTI. • Judgment must be used in interpreting a clean-catch specimen that reports any growth. If the specific gravity of the urine was low, 60,000-80,000 CFU may be significant. Investigations/3 • Lower colony counts may be significant if present on a repeat culture. Contamination with perineal flora may mask an existing UTI. • Urinary tract abnormalities may be associated with multiple organisms. • Cultures with growth of more than 10,000 pure CFU/ml from bladder catheterization or >1000 pure CFU/ml from suprapubic aspiration should be considered significant for UTI. • Urine collected in bags is generally not suitable for culture because of the high incidence of contamination. • Better results may be obtained if the perineum is cleaned and dried before the bag is placed and if the collected urine is removed as soon as the patient voids. Investigations/4 • Cultures from bagged urine specimens are significant only if there is no growth. Cultures from bag specimens should only be used for relatively well children who did not receive empiric antibiotics for fever. In general, young infants with high fever should never have a bag specimen sent for culture given the consequences of difficult to interpret positive culture. • Other Lab findings may include: Electrolyte abnormalities Increased blood urea nitrogen (BUN). Such finding in a child older than 2 months should raise the suspicion of hydronephrosis or renal parenchyma disease. • Any child with proven UTI should have imaging studies performed to R/O VUR or renal anomalies. Imaging studies • Imaging typically is delayed 3-6 weeks after the infection as part of outpatient follow-up, except in cases in which urinary tract obstruction is suspected. • Renal ultrasound • This study adequately depicts kidney size and shape, but it poorly depicts ureters and provides no information on function. • A renal ultrasound can diagnose urolithiasis, hydronephrosis, hydroureter, ureteroceles, and bladder distention and has replaced the intravenous pyelogram (IVP) in many cases. • A voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) adequately depicts urethral and bladder anatomy and detects vesicoureteral reflux (VUR). Imaging studies/2 Nuclear cystography • This study is good for visualizing the bladder and detecting VUR, but it does not show the urethra. • It has only a small fraction of radiation dose (~1%) compared to fluoroscopic study. • It can be used for serial follow-up studies and screening of siblings. Nuclear cortical scanning • This study most frequently uses technetium Tc 99m dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA). • This study detects tubular damage and scarring and shows the kidney outline, but it does not show the collecting system. A The MCU showing a dilated posterior urethra, mildly irregular appearance of the edge of the bladder (reflective and trabeculation) and bilateral vesicoureteric reflux into dilated tortuous ureters. B Hydronephrosis with 'clubbing' of the calyces. Procedure • Catheterization of the urinary bladder or suprapubic bladder aspiration may be required in patients who cannot provide a midstream clean-catch urine sample. • A suprapubic tap is the most invasive diagnostic procedure, but many practitioners view it as the criterion standard despite the potential for gross or microscopic hematuria. Treatment • Emergency Department Care: Treatment must be tailored to the presentation of the patient. • Septic or toxic patients require aggressive management in the ER. Intravenous fluid replacement and parenteral antibiotics should be started after collection of laboratory samples. • Initially, all ill-appearing patients with febrile UTI should be treated with parenteral antibiotics and monitored as an inpatient. The ER consultant or the pediatrician should be informed. • Oral fluids and medications on outpatient basis may be used for patients with cystitis who are less seriously ill at presentation. • Consultation with a urologist is not required at presentation unless there is evidence of obstruction of the urinary tract. Antibiotics • Start antibiotics after urinalysis and culture are obtained. A 10-day course of antibiotics is recommended, even for uncomplicated infection. Do not use short-course therapy in children because it is more difficult to differentiate cystitis from pyelonephritis. An exception is the use of short-course therapy in adolescent females with evidence of cystitis. • Empiric antibiotics for coverage of E coli, Enterococcus, Proteus, and Klebsiella species should be started while waiting the culture & sensitivity results. For cystitis, oral antibiotic therapy is adequate, but if pyelonephritis is suspected, a combination of parenteral antibiotics is recommended. Recent evidence indicates that oral antibiotics are adequate therapy for febrile UTI in young infants and children; short-term (fever) and long-term (renal scarring) outcomes are comparable to parenteral therapy. Antibiotics/2 Amoxicillin Provides bactericidal activity against susceptible organisms, mainly E. Coli, but resistance is reported. Administered parenterally and used in combination with gentamicin or cefotaxime. Pediatric Dose 100-200 mg/kg/d. IV/IM divided q6h. Gentamicin Aminoglycoside antibiotic for gram-negative coverage. Provides synergistic activity with amoxicillin against gram-positive bacteria including enterococcal species. Pediatric Dose <5 years: 2.5mg/kg/dose, IV/IM q8h. >5 years: 1.5-2.5 mg/kg/dose IV/IM q8h. Cefotaxime Third-generation cephalosporin that covers most of the gram-negative Bacteria, but weak activity against gram-positive organisms. Used as initial parenteral therapy for pediatric patients with acute pyelonephritis. May be used for neonates or jaundiced patients. Requires dosing at q6-8h intervals. Pediatric Dose is 100-200 mg/kg/d IV/IM in divided doses. Antibiotics/3 Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole Inhibits bacterial growth by inhibiting synthesis of dihydrofolic acid. Antibacterial activity of TMP-SMZ includes common urinary tract pathogens, except Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Pediatric Dose <2 months: Not recommended >2 months: 510 mg/kg/d PO divided q12h, based on TMP component . Cephalexin First-generation cephalosporin that is useful in simple UTI. Pediatric Dose 25-50 mg/kg PO q6h; not to exceed 3 g/d. Cefixime Third-generation oral cephalosporin with broad activity against gram-negative bacteria. Pediatric Dose: 8 mg/kg PO qd; not to exceed 400 mg/d. Antibiotics/4 Norfloxacin Norfloxacin and Ciproflox acin are potent agents against gram negative organisms. They are used as second line treatment or for recurrent UTI. Nalidixic Acid Specific drug for UTI because it has minimal distribution in tissues and is excreted mainly through the kidneys and reach high concentration in urine. It should not be used in children with G6PD deficiency because it may lead to hemolysis. Follow-up • Hospitalization is necessary for the following individuals: • Patients who are toxemic or septic • Patients with signs of urinary obstruction or significant underlying disease • Patients unable to tolerate adequate PO fluids or medications • Infants younger than 3 months with febrile UTI (presumed pyelonephritis) • All infants younger than 1 month with suspected UTI even if not febrile Complications • Dehydration is the most common complication of UTI in the pediatric population. IV fluid replacement is necessary in more severe cases. Treat febrile UTI as pyelonephritis, and consider parenteral antibiotics and admission for these patients. • Untreated UTI may progress to renal involvement with systemic infection (e.g., urosepsis). • Long-term complications include renal parenchyma scarring, hypertension, decreased renal function, and, in severe cases, renal failure. Take home message • Most cases of UTI are simple, uncomplicated, and respond readily to outpatient antibiotic treatments without further sequelae. • Appropriate treatment, imaging, and follow-up prevent long-term sequelae in patients with more severe infections or chronic infections. • Mild VUR usually resolves without permanent damage. • Any child with proven UTI should have imaging studies performed to R/O VUR or renal anomalies.