Brown892final

advertisement

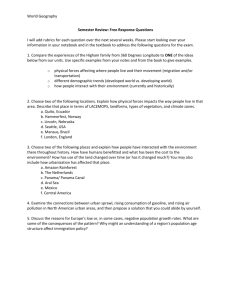

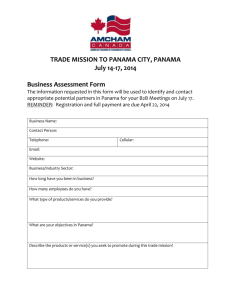

Running Head: EDUCATION IN PANAMA 1 Education in Panama: Inequities, Deficiencies and Solutions Gordon Brown George Mason University Abstract After describing the writer’s social justice disposition and establishing context, this paper will attempt to identify and address apparent deficiencies and inequities in Panama’s education system. Based on evidence such as the most recent data and my own experience and observations, some apparent deficiencies emerged, including: regional/ethnic disparity, literacy, curricular content and delivery, and teacher education and development. EDUCATION IN PANAMA 2 Introduction When my wife and I moved to Panama our Panamanian friends and neighbors told us not to put our children in the public schools. An 11 year-old Panamanian girl in the local school had her arm broken during school when a boy pushed her: the teacher had left the class unattended. Recent reports suggest that Panamanian students perform below average compared to 15 other Latin American countries in all of the assessed subjects: reading, math and science (LLECE, 2008). Last July, 2009, members of the Kuna Indian tribe kidnapped the local Regional Director of the education department because they had been promised repairs to a school more than 4 years ago and were tired of waiting (Jackson, 2009). There seem to be problems with the education system in Panama. What are the problems? And what are the solutions? This paper will attempt to answer those two questions from a social justice perspective. Prior to providing answers, I will define my social justice perspective, and then briefly describe Panama’s history, geography and socio-political systems. Without transparency of the writer’s framework and with no context, the information could be easily misunderstood and misapplied. With my perspective and the context thus established, the paper will try to answer the above questions by identifying and addressing apparent deficiencies and inequities in education in Panama based on evidence. So first, what do I mean by “apparent” and “evidence”? In brief, the deficiencies/inequities met the criteria of apparent and evidence-based by triangulation of my observations, available research and reports from Panamanians. These criteria are influenced by my social justice disposition which in turn impacts the implications for social justice. Therefore, I want to transparently share my perspective of social justice with the reader and further explicate the reasoning behind the process of determining the deficiencies. The Writer’s Social Justice Disposition: A Definition Having read a number of articles and engaged in discourse regarding defining social justice, I’ve come to define social justice as follows: Social Justice: n. the state a society reaches when, regardless of race, color, ethnicity, religion, gender, ability, or sexual preference, at a bare minimum, all members of the society receive basic needs: including adequate nutrition (as determined by the UN and WHO), potable water, sufficient shelter, decent health care, and effective education. In addition, all members of society enjoy EDUCATION IN PANAMA 3 freedom from oppressive violence: oppressive violence in the broad sense, thus, including hunger, slavery, battery, bullying, rape, murder, hate crimes, etc., regardless of race, color, ethnicity, religion, gender, ability, or sexual preference. Finally, social justice is an active noun--like the gerund form of verbs, such as running. It requires social movement in order to be achieved. The movement works to protect and advance the needs of the marginalized, abjectified, oppressed minorities. Thus, this definition does not value one political structure, e.g. democracy, over another, such as communism. Nor is income parity a part of my definition. However, access to sufficient health care and education are highly valued in this definition. And indeed as Sen (1999) cited, expenditures on health and education not only contribute to economic growth, but also substantially improve quality of life (p. 49). Speaking of values, when we decide what oppression is, especially across cultures, we impose our value judgements on other cultures and, may end up inadvertently oppressing the very people we think we are liberating. As Freire (1987) wrote: A good way for educators to affirm their authoritarian elitism is to always express their thoughts to others without ever exposing and offering themselves to others, remaining arrogantly convinced that educators are here to save others…he who hears only the echo of his own words, in a kind of oral narcissism;…he who thinks the working class is uncultured and incompetent and, thus, needs to be liberated from top to bottom—this type of educator does not really have anything to do with freedom or democracy. On the contrary, he who acts and thinks this way, consciously or unconsciously, helps to preserve the authoritarian structures. (p. 40) Gewirtz (1998), cites “Fraser’s concerns about…’normative judgments about the relative value of alternative norms, practices and interpretations, judgments that could lead to conclusions of inferiority, superiority and equivalent value’” (p. 482). Then, considering these concerns within Young’s framework, Gewirtz poses the question, “How, to what extent and why do education policies support, interrupt or subvert…practices of cultural imperialism? And which cultural differences should be affirmed, which should be universalized and which rejected?” (p. 482). EDUCATION IN PANAMA 4 Therefore, to avoid the above referenced authoritarian elitism, oral narcissism, conclusions of inferiority and cultural imperialism, this paper will address issues which have been triangulated, as aforementioned, through international comparative data, intra-nation reports, personal observation, and personal communications with Panamanians. In other words, the issues addressed as deficiencies should pass muster with positivists and cultural relativists alike. Hence, gender will not have a prominent position in this paper—nor will sexual preference, ability, or religious affiliation. Because, while those may be of personal interest and/or currently en vogue in the field, Panamanians do not apparently struggle with those issues—nor do the data suggest any significant disparity. Stromquist (1996) might henceforth accuse me of “not considering exclusions and inequalities affecting women and their limited participation,” and of falling prey to the “deceptive” reports on the education of women in Latin America (p. 412). And, yet, Stromquist embodies the kind of agenda pushing that has resulted in her reliance on a bad combination of unsubstantiated stereotypes and unsupported claims.1 We should not assume other cultures and nations suffer our problems. I have attempted to avoid projecting US problems onto Panama. The following vignette provides a concrete example of my current disposition and a shift in perspective from the cultural imperialist to the cultural relativist end of the continuum. We lived in a very rural part of Panama, in the midst of coffee country. Thus, thousands of indigenous people, mostly of the Ngobe tribe, migrated to pick the coffee from November to March. Part of the Ngobe culture includes fighting. So, my wife and children and I would often come across groups of men beating each other bloody in the street. At first my Western culture thought this barbarically inferior; then my capitalist tendency thought at least they should be getting paid. So, I began devising schemes to “help” these depraved natives. The scheme involved formal instruction in American style boxing (as a former boxing coach I didn’t see much technique in their bouts), combined with mediation services. Thus, we would establish a school of boxing, the Ngobe’s could train for free, but they A) would have to try to resolve differences through mediation before fighting and B) if that failed, they would fight in a sanctioned official venue with a referee (and get paid). I spoke to a Panamanian friend of mine who worked with many Ngobe’s and he described a similar plan he had devised. Then one afternoon I was watching one of the bigger fights, and I noticed that if one of the fighters was getting too badly beaten, the men standing around the circle would intervene and another man would take the beaten one’s place. This led me to two conclusions: 1) These EDUCATION IN PANAMA 5 were sometimes refereed; 2) It was sport—not simply dispute resolution. Further conversation with my Panamanian friend confirmed this: in fact, he had been invited by Ngobe people to an organized fight contest. Moreover, while some of the fights arose from disputes, and often the winner of the fight won the female(s) being contested, there were always rules: including no weapons and no feet. Now I began to notice technique, which consisted of wrestling-style initial moves. So, who was I to judge a cultural practice as inferior or barbaric? Was this any more barbaric than our American organized boxing? Was this violence—that almost never resulted in death—worse than violence in America? In fact, perhaps if we allowed more of this kind of conflict resolution, we’d have less violent deaths in America. Needless to say, I scrapped my schemes for “helping” eradicate this cultural practice. Hence, this paper discusses deficiencies that met the following criteria: 1. I observed them 2. Panamanians described them as deficiencies 3. Data identified them as deficient. The issues that met these criteria include: disparity between rural and urban/indigenous and others, literacy, the curriculum, and teacher education. Gender, sexual preference, and religion did not meet these criteria of deficiencies, but will be discussed as relevant aspects of Panamanian society and education. Before discussion of the issues, some basic background information will construct the context that is the Republic of Panama. Context History The Spanish settled in Panama in the 1500s as part of their colonization of other South American countries (CIA, 2010; Meditz & Hanratty,1987). Of course indigenous tribes, such as the Kuna, Ngobe and Bugle, had lived there for centuries, as evidenced by archeological finds and petroglyphs (Meditz & Hanratty,1987; V. Caballero, personal communications, April, 2006). Panama joined the Republic of Colombia to gain independence from Spain November 28th, 1821 (CIA, 2010; Meditz & Hanratty,1987). With assistance in the form of a Navy presence from the US, Panama declared independence from Colombia November 3rd, 1903 and immediately signed a treaty allowing the US to build the Panama Canal (CIA, 2010; Meditz & Hanratty,1987; McCullough, 1977). The US tired of negotiations with Colombia over what was by most assessments a reasonable price to pay (McCullough, 1977). This revolt did not entail much actual fighting (McCullough, 1977). Ironically, some of the most intense fighting was lead by Victoriano Lorenzo, of indigenous ethnicity, who some claim was the first Latino EDUCATION IN PANAMA 6 revolutionary and mostly responsible for the victory (Muller-Schwarze, 2008; P. Calavera, personal communication, January, 2010). Given Lorenzo’s vital role in independence, the irony is that the indigenous are the only categorical group who suffer injustice in the education system as per the above established criteria. Some Panamanians blame the nation’s relatively painless birth for what they perceive as a cultural lack of initiative: a laziness and reliance on others for help (A. Tello, C. Cabrera, V. Ortiz & P. Calavera, personal communications, 2006-2009). General Omar Torrijos took power in 1969 and began his rule of self-described “dictatorship with a heart” until his plane crashed in 1981 (Meditz & Hanratty, 1987, History, Torrijos Sudden Death section, para. 1). The United States—and specifically George Bush Sr. under the Reagan administration—is often implicated in his death, though the crash is still ruled an accident (Greene, 1984; Harris & St. Malo, 1993; A. Tello & G. St. Malo, personal communication, 2006; P. Peterson personal communication, April, 2010). General Torrijos, considered a socialist and friend to the people, was obsessed with education and is credited with great leaps forward in Panama’s education system (Meditz & Hanratty, 1987; P. Peterson, personal communication, April, 2010; Greene, 1984). Under his administration many schools were built and Panama’s modern system was firmly established (Meditz & Hanratty, 1987; P. Peterson, personal communication, April, 2010; Greene, 1984). After brief interim leadership, General Noriega--with US support--assumed power and began a brutal rule . Noriega’s rule ended when the US decided to interfere with Panama and used heavy artillery and military forces to hunt and extradite him (CIA, 2010; Harris &St. Malo, 1993; A. Tello, personal communication, 2006). The Panamanian Problem, by Harris and St. Malo (1993), documents the disintegration of diplomatic efforts, placing most of the blame on the US. Thanks to the late General Torrijos, President Carter and the Carter-Torrijos treaty, the Panama Canal and other US holdings reverted to sovereign control in 1999 (CIA, 2010; Muller-Schwarze, 2008). Government and Population Since the violent removal of General Noriega, Panama has been a constitutional democracy, with the same three branches of government as the United States: executive, legislative and judicial (CIA, 2010). The current president, Ricardo Martinelli, a wealthy businessman educated in the US, beat his main opponent Balbina del Carmen Herrera Arauz, a woman many considered a Noriegista with ties to Chavez, in a relative landslide (V. Caballero, A. Tello & M. Caballero, personal communications, 2008-2009). Presidential terms last five years EDUCATION IN PANAMA 7 (CIA, 2010). Traditionally if a newly elected president of Panama comes from an opposition party, all government employees--down to maintenance and maid service--are replaced by party loyalists (I. Agosto, D. Santos, M. Caballero, personal communications, 2008-2009). President Martinelli seems to be ignoring that tradition. He appointed Lucy Molinar, a popular television personality and consistent critic of Panama’s education system, the Minister of Education. She has no background in education. The total population of Panama comes to approximately 3, 360, 000—a little more than the population of metro-DC (CIA, 2010). Infant mortality rate at about 12% is twice that of the US and in the middle of Colombia’s and Costa Rica’s, but the overall death rate of about 4% is half that of the US (CIA, 2010). So, current life expectancy is 77, with women living past 80 and men past 74 (CIA, 2010; UNICEF, 2010). 1% of adults have HIV/Aids (CIA, 2010, UNICEF, 2010). Approximately 85% are Roman Catholic while most of the remaining 15% are Protestant (CIA, 2010). Approximately half of the population live in the capital, Panama City. In 2004 Panama spent 3.8% of GDP on education; from 1998 to 2007 16% of public expenditures went towards education (CIA, 2010; UNICEF, 2010). Geography Panama, the bridge between the continents and the path between the seas, floats between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean anchored to Costa Rica on the North American side and to Colombia on the South American border (CIA, 2010). Its approximately 75,000 square miles make it a bit smaller than South Carolina (CIA, 2010). Yet its terrain ranges from 0 meters (sea level) to 3, 475 meters on the summit of Volcan Baru, the highest peak in the region (CIA, 2010; Focus, 2006, pp. 83-86). From that summit one can see the Atlantic ocean to the north and the Pacific to the south (though in the three times I hiked it I only saw one ocean once due to inclement weather and poor visibility). Indeed, Panama’s variegated flora, fauna and land formations have attracted Europeans for centuries. Panama boasts more varieties of insects, flowers and birds than practically anywhere else on earth. The island Coiba off the Pacific coast is a designated World Heritage Site comparable to the Galapagos for its “high levels of endemism of mammals, birds and plants” (Focus, 2006, p. 115). In addition, tourists can enjoy beautiful beaches, natural hot springs, white water rafting, and hikes through cool rain and cloud forests within a one hour drive-time radius. The climate is tropical and results in two seasons: rainy from April to December and dry from January to March.2 EDUCATION IN PANAMA 8 Context matters. The history, government, population characteristics, and geography of Panama have had—and continue to have—significant impacts on key aspects of Panama’s education system: from the daily and annual schedule (which are organized to avoid the rainy time of day and independence celebrations during the month of November), to the gap between indigenous and majority achievement which will be discussed below. Equity: Where’s the Gap and Who’s Oppressed? Religious Affiliation and Sexual Orientation My entire time in Panama I never heard of a hate crime, nor any incident of oppression against another human based on their religion nor sexual preference. In fact, despite the above referenced overwhelming majority of Catholics with Protestantism accounting for most of the rest, there are Buddhists, Mormons, Jews, Seventh Day Adventists, indigenous faiths and other religious groups with enough members to build temples and churches (though apparently not enough members to be mentioned in the CIA (2010) World Fact Book). Indeed, Harris and St. Malo (1993) devote a section of their book to the response of the Jewish community in Panama to the Noriega situation. These minority religions coexist in apparent harmony among the Catholic majority. Likewise, I met Panamanian homosexuals and spoke with a number of Panamanian high school students about views on homosexuality. Panamanians invariably stated that homosexuals are not necessarily celebrated but they are accepted—nobody seems to care much about sexual preference. Furthermore, most of the young Panamanians claimed that even those who everyone knows are homosexual are not victims of bullying, hate crimes, or the like. Indeed I got to know one high-ranking Panamanian official who was openly gay and seemed not to suffer persecution nor undue attention for it. However, it may be that this issue has not been confronted, and it should be investigated further. Nevertheless, based on the lack of data, personal communications and field observations, neither sexual preference nor religious affiliation met the criteria for categories suffering from apparent inequitable treatment under the Panamanian education system. Ability When you log on the web site for the Ministerio de Educacion (MEDUCA) there is a button for statistics, but when you go to that page the links to the actual statistics don’t work. Right under the statistics button is a button for “educacion inclusiva” (tr. inclusion). That button leads to many links with documents, including the “Plan Nacional de Educacion Inclusiva” (tr. National Plan for Inclusion). This impressive five chapter document EDUCATION IN PANAMA 9 discusses how to serve all children in public education in the least restrictive manner, regardless of severity of disability, and includes specific suggestions for schools, curricula and teachers. I personally knew a number of children who had disabilities and were adequately served in the public schools, including children who were diagnosed MR and one girl who suffered from Rett syndrome (P. Garcia & I. Agosto, personal communications, 2006-2008). Despite the occasional problem, her parents were satisfied with the service they received (P. Garcia, personal communication, January, 2009). In my capacity as supervisor, I observed a number of teachers. All of them had children with disabilities in their classrooms. During observations they would often acknowledge the children who had the disability and on occasion would make statements to the effect of, “S/He is very special so s/he can’t do this.” Which, being that these statements were made in front of all the children, was probably not the best practice. However, the teachers seemed to have a good rapport and connection with the special students. They did not have support staff, such as a special educator, in the room. I did observe one special educator, and on that day her student was much better served than the regular education students, who were largely ignored by their regular education teacher. In any case, laws governing special education in Panama and the resulting practices are similar to those in the US, that is, all children regardless of disability have the right to public education (MEDUCA, 2010; A. Gonzalez, personal communication, 2009). Thus, education of diverse abilities did not meet the criteria for a category suffering apparent inequitable treatment. However, ability will be revisited in the discussion of solutions. Gender Gender presents a more complex conundrum. Panama seems to nurture gender roles: my daughter was subjected to becoming a princess in pre-school. In fact, princess culture runs rampant in Panama: every grade in every school—including at the university level—holds princess contests and pageants. In addition, villages and districts select princesses to represent them and reign during parades for carnival, Christmas, etc. Women are not welcome in billiards halls and other types of male-oriented bars. A woman entering such an establishment wouldn’t be thrown out, necessarily, but would be considered of low morals. And, in fact, prostitution is legal and most prostitutes are women. When my wife and I attended private birthday parties I was offered beer or rum, she was not offered anything. Many members of the Ngobe tribe still expect girls to start making babies at the age of 12 and the goal is to birth at least 10 children; the men still win the women by fighting for them; the women walk a EDUCATION IN PANAMA Figure 1. Minister of Education, Lucy Molinar 10 couple of feet behind the men. I personally knew of some situations in which men physically abused their wives and/or committed adultery. The women I knew in these situations generally divorced the men in question, suggesting that those behaviors may not be accepted cultural practices. Our Western concept of civilization may consider some of the above reprehensible and/or backward. Yet, if we take a moment to consider our own issues with gender, by looking at rape statistics, domestic violence and other violent crimes against women in the US, as well as divorce rates, then who are we to judge? Like the above described case of Ngobe fights, perhaps gender roles have a positive impact on gender relations. Maybe legalized prostitution reduces violence against women. I don’t know. Certainly, some of the above social phenomena and relationships, from roles as princesses to prostitutes, may indicate that Panama’s societal superstructure subjugates women and/or worships women for physical/sexual traits. On the other hand, Panama has elected a female head of state—the US still has not. More to the point, in the field of education—the topic of this paper—women enjoy parity, and, indeed, it could be argued that men have fallen to the low end of the gender gap. Women hold most of the teaching jobs as well as school leadership positions: in fact, the current chief educator, Ministra Lucy Molinar, is female (see Figure 1). Furthermore, the data for a number of bench marks, such as attrition, demonstrate parity or males falling behind. The gap in literacy is not significant: males at almost 93% literacy edge females at approximately 92% by about 1% (CIA, 2010). But females with an expected school life of 14 years, edge out males at 13 years, by an entire year (CIA, 2010). Indeed, in a recent conversation with Price Peterson, a director of the University of Honduras and consular warden for the Boquete District in Panama, he revealed concern for a potential societal crises arising from the substantial gap between the numbers of Panamanian women graduating from universities vs. their male counterparts. The most recent data from UNESCO’s Institute for Statistics confirm this trend with 5-6% more females enrolled in secondary schools than males and female enrolment in tertiary education beating that of males by more than 20% in 2007 and 2002 (UNESCO, 2010). In addition, on the recent Second Regional Comparative and Explanatory Study (SERCE), third grade girls outperformed third grade boys on the reading assessment by close to 15 points; by the 6th grade the gap increased to EDUCATION IN PANAMA 11 more than 15 points. In math, the SERCE showed third grade girls beating the boys by nearly 6 points; by sixth grade, boys began closing the gap and were only down by about 3 points. Thus, whether looking at enrollment, attrition, university graduation rates, performance on regional math and reading assessments, or employment in the field of education, females enjoy parity, and in fact, superiority in Panama. Therefore, being that the focus of this paper is education and not the societal costs or benefits of princesses and prostitutes, gender did not meet the criteria for a category suffering from apparent inequitable treatment in education, with the exception of attrition of males, which will be revisited briefly in our discussion of solutions. Rural Districts and Race The same above mentioned SERCE, which was a UNESCO published comparative assessment of 16 Latin American countries, showed great disparity between rural and urban populations (LLECE, 2008). Third and sixth grade urban students in Panama scored more than 50 points better on the reading assessments. On the math assessments the gap grew, with third grade urban students scoring just over 20 points better--but by sixth grade almost 40 points better--than their rural counterparts. So who are these rural students? The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) (1998) provides pragmatic demographics of race: The majority of the population is made up of nonindigenous groups (91%), which include Hispanics (the majority), descendants of African slaves, and descendants of African slaves from the West Indies. The rest of the population is indigenous (9%), divided among five groups: Kuna, Emberá and Wounaan, Ngobe-Buglé (previously known as Guaymíes), Bokotas, and Teribes. From my observations and experience, most of the indigenous minorities, now close to 10% of Panama’s population, live in the rural areas. Meditz and Hanratty (1987) allude to this correlation between the indigenous and rural populations when speaking of the disparity in literacy rates: The most notable disparity was between urban and rural Panama; 94 percent of city-dwelling adults were literate, but fewer than two-thirds of those in the countryside were--a figure that also represented continued high illiteracy rates among the country's Indian population. (Education section, para. 3) EDUCATION IN PANAMA 12 In many cases the indigenous live in very remote areas, with no modern infrastructure such as roads, plumbing and electricity. Often they live hours away--by foot--from the nearest school and clinic. These harsh living conditions sometimes result in tragic consequences: a Ngobe friend of mine suffered the loss of his twentyyear-old daughter to influenza during an outbreak in which more than 1003 Ngobe children died. Access to basic health care would have saved them. This happened in 2007. That October, reports of Ngobe children dying in the Nurum district of Panama’s indigenous Ngobe-Bugle region began surfacing. Officials reported more than 40 deaths from what would initially appear as a flu-like virus, but would present symptoms indicative of bronchial pneumonia before killing its victim. Government officials attributed the problem to complications from rainy season colds and poor sanitary conditions and reported just 10 deaths. Thus, due to what they perceived as a lackadaisical response, the local officials began contacting the news media. The region is extremely remote and many of its inhabitants live a many hours walk from the nearest passable road. This inhibits both the flow of accurate information and health-care services. As news of this outbreak spread, President Martin Torrijos was visiting the United States. He left the US ahead of schedule and flew into the district with more than 50 healthcare workers to advise families there to cooperate with health officials and bring their children to hospitals (Jackson, 2007). Eric Jackson (2007) wrote in the on-line publication The Panama News: The Ngobe-Bugle Comarca, the youngest of Panama’s semi-autonomous indigenous regions, comprises about nine percent of the country’s land mass and by all accounts has its biggest concentration of poverty. Many of the inhabitants leave for part of the year to pick coffee or other crops. Panama’s long-standing compulsory public education laws are mostly theoretical there. (para. 8) Yet, despite “economic marginalization, political atomization, difficult access and cultural breakdown…The area is home to the largest, most persistent and most volatile swing vote in Panamanian politics” (Jackson, 2007). Perhaps it was for this reason that President Martin Torrijos spent a lot of time there, or perhaps he inherited some of his father’s obsession for education and commitment to the poor. Regardless, the former President frequented the region to promote his Network of Opportunities program. The program, based on similar efforts in Venezuela and Brazil, pays mothers $35 stipends if they ensure that their EDUCATION IN PANAMA 13 kids recieve innoculations and go to school. Torrijos personally flew in to remote communities to deliver the envelopes with $35 to local mothers, posed for photographers and gave speeches hoping to win the indigenous vote. While living in Panama, I sensed that the indigenous were nearing the end of the climax of their civil rights movement, thus, analagous to circa 1970 for African-Americans. Marches and demonstrations seem to have intensified at the end of the last millenium and the CCCE (similar to SNCC for the African-American movement) was formed in 1999 (Muller-Schwarze, 2008). The battle for land has been documented as an ongoing struggle since the Spanish arrived in the 1500s (Muller-Schwarze, 2008). Indeed, the aforementioned Victoriano Lorenzo fought for independence in return for a promise of land for his tribe (Muller-Schwarze, 2008). In recent decades tribes have received, yet again, grants of territories, such as the Comarca territory, as well as virtual autonomy, e.g. the Kuna tribe and San Blas islands (Muller-Schwarze, 2008). Yet, unfortunately, the indigenous battle for land continues--largely due to trans-national development projects such as dams and the canal expansion which threaten their way of life, their sustenance and their homes (Muller-Schwarze, 2008; Perkins, 2004). In addition to battling for land, they still suffer racism, poverty, hunger, and other forms of oppression. The Kuna tribe recently decided to wage their battle in the field of education. Apparently frustrated by long delayed, promised and overdue repairs to one of their schools, this past July, 2009, they kidnapped a MEDUCA regional director—the equivalent of a superintendent in the US. When the responsible parties met with them to establish a firm date for the repairs to begin, the Kuna released the director unharmed (see appendix A for a report of the incident in English). As part of the Professional Development School (PDS) I founded in Panama, I brought in a panel of diverse students and parents to talk with the teachers in the program. All of the panel members were indigenous; some of them had experience with disabled family members; one was university bound, one was enrolled in university and one dropped out of school after fourth grade. This panel felt they had generally been treated equitably in the public schools, but there were incidents. For example, one told of a class where a Panamanian student referred to an indigenous classmate as a cholo, a derogatory term for indian. The other students laughed. Rather than chastising the bully, the instructor seemed to laugh as well. Casa Esperanza is a nation-wide after-school organization specifically designed to narrow the achievement gap between indigenous children and the rest. The quality and scope of services provided is impressive and EDUCATION IN PANAMA 14 includes health care, homework help, access to technology, instruction in music and art and literacy programs. I worked with the Casa Esperanza site in the Boquete district of Panama. At that site alone the organization served more than 200 students daily. Hence, given the above, particularly: the urban/rural disparity in literacy; the demand for programs targeting indigenous school children such as Casa Esperanza and the Network of Opportunities; and the recent kidnapping of a high-ranking educational leader, the category of race—specifically the indigenous races—qualifies as suffering apparent inequitable treatment in the Panamanian education system. Literacy4 There are two reasons why I’ve given literacy—often defined by the ability to read and write—it’s own section separate from the curriculum. First, literacy, more than other disciplines, is considered crucial to sociopolitical empowerment, economic growth, and academic success across disciplines (Sen, 1999; Freire, 1987; EFA, 2006; CIA, 2010). Second, the literacy data in Panama is problematic. As reported by Molina (2008) in Panama’s premier newspaper, La Prensa, “La incapacidad de interpretar textos les impide aprender de forma adecuada el resto de la vida escolar.” (Tr. The inability to interpret texts impedes adequate learning for the rest of academic life.) But literacy is not just important for academic achievement; literacy possesses pragmatic purposes. The on-line World Fact Book of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) succinctly highlights the practical application of literacy with the statement, “Low levels of literacy, and education in general, can impede the economic development of a country in the current rapidly changing, technology-driven world” (References, Definitions and Notes, Literacy section, para. 1). Other documents, such as the 2006 Education For All (EFA) Global Monitoring Report, declare literacy a human right (p. 27). Whether considering literacy as a building block for academics, stimulant for economic development, a human right, or all of the above, most of us believe it is of vital importance. Literacy is commonly defined as the ability to read and write (CIA, 2010; Funk & Wagnall, 1949; Encarta, 2010; EFA, 2006). The EFA (2006) adopted UNESCO’s (1978) definition: A person is functionally literate who can engage in all those activities in which literacy is required for effective functioning of his group and community and also for enabling him to continue to use EDUCATION IN PANAMA 15 reading, writing and calculation for his own and the community’s development. (as cited in EFA, 2006, p. 30) In order for literacy data to be more meaningful, I believe we need to more narrowly define literacy by incorporating a comparative level and skills as follows: adult literacy refers to anyone over the age of 15 who reads, writes, comprehends and uses technology at a sixth grade level or higher. For the past 20 years the alleged literacy rate in Panama has hovered around 90%, apparently slowly improving from 89.3% in 1990 to 93.4% in 2008 (PAHO,1998; CIA, 2010; EFA, 2010). However, despite the legitimate authority of the organizations reporting this data, I question it. I question it because, as the EFA (2006) admitted, “the literacy rates reported by the EFA Global Monitoring Report are among the weaker international education statistics” (p. 30). One of the problems with the statistics are the varying definitions: in some countries if a person could only read or only write they would be classified as literate, in others illiterate (EFA, 2006, p. 174). In fact, “In past censuses, the ability to sign one’s name was sometimes considered as sufficient evidence of literacy” (EFA, 2006, p. 174). Often simply being promoted to 4th grade qualified one as literate according to the authorities, whether or not the person in question could read or write (EFA, 2006, pp. 156-157). Thus, I have many questions about the literacy data that require further investigation. How was adult literacy in Panama defined? Based on that definition, what assessment was implemented? My eight-year old son could pass the above-quoted EFA definition, which is perhaps a bit more rigorous than the standard definition “the ability to read and write” (CIA, 2010; Encarta, 2010; Funk & Wagnall’s, 1949). None of the definitions set a level that could be evaluated and assessed. So, if the determining instrument is a survey that asks the question, “Can you read and write?” and the proof is that they read the survey and responded—as per the 1994 method in Kenya--that may not be demonstrative of literacy above a second-grade level (EFA, 2006, p. 156). Furthermore, who gets counted in the data? Are the data collectors sampling? Did they hike five hours into the Comarca territory where many of the indigenous live? Are they giving the literacy assessment in multiple languages, such as the indigenous Ngobe and Kuna Yala languages, or just Spanish? Based on my observations and triangulation through personal communications, this issue of literacy became an apparent deficiency for a number of reasons including: the lack of lending libraries and bookstores; the EDUCATION IN PANAMA 16 lack of fiction stories in k-12 schools; and the cultural lack of reading for pleasure or information. In addition, I kept meeting Panamanian adults—not just indigenous—who could not read nor write. Moreover, when you combine the SERCE data with retention data and attrition data,5 and if adult literacy is assigned a measurable and decent level, e.g. sixth grade, then I fear the reported literacy rates in Panama would be much lower. Take the 6th grade reading performance on the SERCE and combine that with rates of enrollment past the 6th grade: while enrollment in primary is about 100%, graduation from primary—i.e. sixth grade—is just 88%, and enrollment in secondary schools female:male dips down to 73%:68% (UNICEF, Info by Country: Panama, Education section). Now consider the following excerpt’s discussion of retention, i.e. the percentages of students in Panama who are older than the “norm” for their grade level (of course, if more than 50% are in that situation, as per below, one could argue that is the norm). Otro dato que sirve para medir la calidad del sistema se encuentra en la cantidad de estudiantes que se encuentran por encima de la edad del grado que cursan. Las estadísticas del Meduca señalan que en el nivel primario, por ejemplo, existe un 34.5% de alumnos en esta situación. En la premedia y media, el porcentaje sube a 51.4%. (Benjamin, 2006). Translation: Other data that measures the quality of the education system is the number of students who are older than the norm for their grade level. Statistics from MEDUCA state that at the primary level 34.5% of students are in that situation. In the elementary and middle years, the percentage rises to 51.4%. Let’s add to our analysis of the variables the SERCE results for 6th grade reading: 69% of students in Panama scored at level II-IV, 31% scored at level I or below (LLECE, 2008). While not perfectly transferable, I’m going to equate level I or below on the 6 th grade assessment with not yet adult level literacy. Let’s go ahead and paint the picture by numbers now. As per the above: 50% of children reach the 3rd grade unable to read; at least 35% of those third graders are older than the norm; 88% of Panamanian children graduate from 6th grade; approximately 70% go on to 7th grade; more than 50% of those 7th graders are older than the norm. If we were to define literacy as the ability to decode and comprehend text and write in Spanish, English or one of the indigenous languages at the 6th grade level, then, by the above analysis, I fear the reported 94% adult literacy rate in Panama would drop by at least 20 points to around 70%. EDUCATION IN PANAMA 17 Neither the scope of this paper nor the resources of the author allowed for a rigorous statistical analysis. Therefore, researchers should investigate literacy data diligently. Moreover, nations and organizations, such as UNESCO, should consider raising the standard for literacy and applying that standard across nations. In my opinion the ability to sign your name does not make you functionally literate. The Curriculum: Bolitas y Bailando The casual observer might—not entirely incorrectly—get the impression that the pre-k-2nd grade curriculum consists mainly of tearing paper, rolling it into bolitas (tr. little balls) and pasting the balls in to a prescribed pattern; that and bailando (tr. dancing). With in-class work and homework, my son and daughter rolled and pasted tens of thousands of bolitas between them (see Appendix B). My daughter began learning traditional dance in pre-k and participated in the school dance performance from the age of 4 on. Just getting the girls dressed in the traditional gowns and made-up took more than two hours, and the purchasing of hair accessories, ironing of the pleated dresses, etc. begins weeks before the performance. I’m not suggesting that bolitas and bailando be removed from the curriculum entirely; however, the time dedicated to those two skills seems a bit excessive and perhaps some of that time could be dedicated to other concepts, such as basic operations in math, or reading comprehension. I recently spoke to two Panamanian educators, one pre-service English teacher and another Coordinator of a University English Program and high school English teacher. I asked them if they could change anything in Panamanian education what would they change: the curriculum showed up high on both of their short lists (C. McLaughen & Y. Garcia, personal communication, May, 2010). They both felt it was incomplete and needed to be improved. In fact, when I spoke to her last week, the coordinator was off to present some of her research on curricular changes she had implemented in the high school English program to improve verbal fluency (Y. Garcia, personal communication, May, 2010). As parents of children in the school system we felt there were some problems with the curriculum. As a supervisor for some teachers in Panama these feelings were confirmed. The main problem seems to be too much rote copying and memorization, not enough conceptual understanding nor critical thinking. To illustrate let’s examine the math curriculum. EDUCATION IN PANAMA 18 Figures 2 and 3 display standards 1 and 2 for third grade in mathematics. To summarize them in English: Standard one requires students to be able to read, write and count whole numbers up to (and down from) 9,999, by ones, twos, threes, fives, tens, hundreds and thousands (see Figure 2). Standard two requires students to be able to comprehend the concept of addition and apply it to addition problems with totals less than 9,999 (see Figure 3). On the MEDUCA web site you can also find the curriculum guide for environmental education. This sixth edition integrates environmental education with the other disciplines, such as math. The third grade math section of the guide has a lesson plan titled “Las patas de los animals” (Tr. The legs of animals; MEDUCA, 2007, p. 28). The objective is to construct the multiplication table from problems posed with numbers of the legs of animals, e.g. Spiders have eight legs; there are 5 spiders in a spider web; how many spider legs are in that web? (Ans. 8 legs x 5 spiders = 40 spider legs in the web). That’s not a bad lesson. The problem is that the second grade lesson from the same guide has students working on counting items in the environment, e.g. stones in the school patio, leaves on a small plant, trees in the field, up to 999. Moreover, while the ESTÁNDAR DE CONTENIDO Y DESEMPEÑO NO. 1 ÁREA: LOS NÚMEROS, SUS RELACIONES Y OPERACIONES Comprender el concepto de un número natural y utilizar el sistema de base diez para representarlo Tercer Grado. 1.18 Comprender el concepto de unidad de millar 1.19 Distinguir el valor absoluto y posicional de las cifras para escribir y contar números naturales hasta 9,999 1.20 Realizar la lectura y escritura de números naturales hasta 9,999. 1.21 Aplicar el conteo progresivo y regresivo de números naturales hasta 9,999. 1.22 Aplicar el conteo progresivo y regresivo de números naturales desde 999 hasta 9,999 de “dos en dos” ; “tres en tres”; “cinco en cinco”; “diez en diez”; “cien en cien”; “mil en mil” 1.23 Construir familias de números naturales de manera progresiva y regresiva ordenándolas según la cantidad que representan en la recta numerada hasta 9,999. 1.24 Utilizar la recta numérica para representar los números naturales como puntos de la recta hasta 9,999. 1.25 Aplicar las relaciones de orden entre números naturales hasta 9,999 ( relación “antes de”, “después de” y “está entre” ). national curriculum does Figure 2. From Estándares De Contenido y Desempeño. MEDUCA (1999). EDUCACIÓN have students beginning to learn multiplication PRIMARIA tables in second grade, in my experience, even third grade students MATEMÁTICA have trouble with the more basic operations of addition and subtraction due to an overemphasis on standard one to the detriment of the other standards. So, the guide lacks vertical integration because its second grade lesson does not include any operations, then the third grade leaps to multiplication in word problems. Moreover, while on paper it appears to be aligned with the national math standards, in praxis, I fear that many Panamanian third graders struggle with multiplication. EDUCATION IN PANAMA 19 ESTÁNDAR DE CONTENIDO Y DESEMPEÑO NO. 2 ÁREA: LOS NÚMEROS, SUS RELACIONES Y OPERACIONES Comprender y aplicar el concepto de adición o suma de números naturales, sus propiedades y procedimientos de cálculo en la resolución de situaciones problemáticas reales o hipotéticas Tercer Grado. 2.19 Comprender el concepto de adición o suma de números naturales. 2.20 Aplicar la composición y descomposición de números naturales para realizar sumas con totales menores 9,999. 2.21 Comprender el algoritmo de adición o suma en los números naturales. 2.22 Aplicar el algoritmo de adición o suma en los números naturales con totales menores a 9,999 2.23 Aplicar las propiedades de la adición o suma en los números naturales. 2.24 Estimar adiciones o sumas de números naturales cuyo total sea menor de 9,999. 2.25 Calcular mentalmente adiciones sencillas de números naturales con dos sumandos cuyos totales lleguen hasta 9,999. 2.26 Resolver ecuaciones de la forma a+__= c, o de la forma __+ b = c para totales menores de 9,999. 2.27 Formular y resolver problemas reales o hipotéticos de adición o suma en los números naturales hasta 9,999. Figure 3. From Estándares De Contenido y Desempeño. MEDUCA (1999). Through a mentor program I implemented at a home for abandoned children, I had the opportunity to work with many children at different grade levels. I distinctly remember working with a 10-year old we’ll call N, who was busy filling pages by writing to 5000 by ones, twos, threes, and fives. Sometimes he’d get stuck, and I’d prompt him by asking, “Well, what is 3, 408 plus 2?” He generally responded to these suggestions of mine to use addition to figure out the next number in the series with a blank stare followed by incorrect guesses. He was not the only one to respond thusly. So, I found myself often teaching the basic operations, such as addition and multiplication, to students aged 8-14. I’m not saying Panamanian elementary teachers don’t spend any time on operations. But I did see notebooks full of numbers written to satisfy standard one. And I worked with many 8 through 14 year olds who struggled with addition and subtraction and did not know their multiplication tables. So, my suggestion would be to focus less on the rote copying of series of numbers and more on the concepts of basic operations; that is, less time mastering standard one and more time mastering the other standards. Generally speaking, in Panama the focus on rote memorization and copying should be reduced and higher order thinking skills as per Bloom’s Taxonomy emphasized (Bloom, 1956). The university students I worked with in Panama could copy pages from books, but properly summarizing text was a skill they had not mastered. I observed teachers at the elementary and secondary levels copying pages of text books on the board which the EDUCATION IN PANAMA 20 students then copied in their notebooks for the entirety of the 40 minute period. When my son was in first and second grade, my wife and I and his baby-sitters spent many afternoons helping him memorize sections of notes that had been pasted into his notebooks, so that he could write or speak the answers to the tests verbatim. Meanwhile, we spent other afternoons purchasing accessories for my daughter when she was 3 and 4 years old, so that she could meet the requirements of the dance performances in pre-school (see Figures 4 and 5). Of course, none of that compares to the years my son and daughter spent tearing what seemed like tons of strips of paper to roll into thousands of bolitas and paste into patterns in their notebooks (see Appendix B). Figure 4 My daughter pre-performance. Figure 5: Panamanian folk dancing performed by 3-4 year-old children. I have nothing against developing fine motor skills by tearing and rolling tiny pieces of paper (particularly applicable motions to coffee picking). And I enjoy dancing and watching children folk dance. In fact, I hope Panama does not over-react in the way the US and the UK did with the NCLB and Literacy and Numeracy initiatives respectively, which have drastically diminished instruction in the arts and stifled effective methods for balanced development. Keep on dancing. Keep some of the bolitas and bailando. However, given the extremely poor results of the SERCE, and in light of the relatively high investment Panama devotes to education, I think the curriculum needs to be revised: specifically, concepts and learning strategies should be emphasized and rote memorization should be de-emphasized. Perhaps small changes, such as, reordering the national math standards for third grade, such that the operations of addition, subtraction, multiplication and division are standards numbers 1, 2, 3 and 4, whereas, EDUCATION IN PANAMA 21 counting to 9, 999 is standard number 5, would have a symbolic and pragmatic effect resulting in desirable outcomes. Teacher Preparation and Development A variety of paths to licensure as a k-12 teacher exist in Panama:1) one may get an undergraduate degree in education; 2) one may get an undergraduate degree in a subject such as math or science, and then a master’s degree in education; 3) there is one high school program, in Santiago Normal high school, which has a teacher preparation program as part of the 10th – 12th grade curricular options. According to the educators I spoke with, these programs include teaching internships that may range from one month to four months in duration (A. Gonzalez, personal communication, 2009; C. McLaughen & Y. Garcia, personal communication, May, 2010). A pre-service teacher pursuing a master’s degree or Ph.D. also does a research project (C. McLaughen & Y. Garcia, personal communication, May, 2010). Upon graduating, the teachers submit all of their paperwork to MEDUCA and they may apply to certain schools—particularly at the university level—but traditionally MEDUCA then assigns the new teachers to rural schools where they work for 1-2 years after which they can apply for a transfer (A. Gonzalez, personal communication, 2009; C. McLaughen & Y. Garcia, personal communication, May, 2010). However, according to Professor Garcia, the placement of teachers is becoming more politicized such that teachers with connections get placed where they want without having to do time in rural schools (Y. Garcia, personal communication, May, 2010). Interestingly, she feels this freedom of choice will be detrimental to efforts to close the rural/urban achievement gap. Whereas, other educators I spoke with saw the centralized control of teacher placement as a cause of numerous problems, including teacher shortages and job dissatisfaction (L. Fennario & C. McLaughen, personal communication, 2008). So, what’s the problem? Well, for one thing, when the 2008 SERCE shows that Panamanian students performed below average on every indicator: reading, math and natural science in both 3rd and 6th grade as compared to 15 other mostly poorer Latin-American countries, I believe it’s reasonable to review how educators are being trained. The New York Times Magazine recently ran an article suggesting a similar link between teacher preparation and student achievement—La Prensa was two years ahead of the Times (Green, 2010; Molina, 2008). The 2008 article discussing the results of the SERCE in La Prensa cites Pedro Ravela, a consultant for UNESCO, EDUCATION IN PANAMA 22 as suggesting that A) teachers need to be paid better, and B) continuing education for teachers needs to improve and include more observations (Molina, 2008, para. 3). So, while Meditz and Hanratty (1987) claim that “Teacher education was a high priority in the 1970s and 1980s, a reflection of the generally poor training teachers had received in the past,” apparently the priorities were ill-conceived and ineffective (Education section, para. 13). Unfortunately, I bore witness to the results of poor teacher training. Effective homework practice, e.g. brief practice of learned skills, was not followed. In second grade in Panama our son usually had two hours of homework every night, and often the directions were unclear. This past year in second grade in Fairfax he averages 20-30 minutes of homework, 4 nights a week; the directions are clear, and, most important, his improvement in all disciplines, most notably reading and writing, is substantially greater. As previously mentioned I supervised some teachers and thus observed and evaluated a number of educators. I saw teachers copying texts on the board and students copying the notes into notebooks. But I discovered the worst case of poor teacher practice at the same public elementary school where our 11 year-old neighbor broke her arm while the teacher was out of the room. It turns out teachers in that school regularly left their classrooms unattended while they chatted or had meetings. This is a basic safety issue and a violation of Panamanian law. The demand for my pilot PDS program by teachers, parent organizations and the university partner was further evidence of a need for better teacher training. This demand derived in part from the fact that, according to numerous educators, MEDUCA has given the same in-service training every February for many, many years, despite the annual promise that next year they would change the program (A. Gonzalez, C. McLaughen & Y. Garcia, personal communications, 2008). The PDS experience in Panama brings us to implications and solutions. Implications and Solutions The Path Between the Seas and Bridge to the Americas: Trailhead/Port of Embarkation "The cultural heritage given to the child should be determined by the social position he will or should occupy. For this reason education should be different in accordance with the social class to which the student should be related." Declaration of the First Panamanian Educational Assembly, 1913 (as cited in Meditz & Hanratty, 1987) Before we begin discussing implications and suggesting solutions, we should remember that Panama’s history as a completely independent nation at barely over a century is even shorter than that of the United States. I EDUCATION IN PANAMA 23 had a Panamanian neighbor who was older than the country itself: born in the republic of Colombia. In addition to the birth of her nation, in her life she saw the following changes in education: 1913 The First Panamanian Educational Assembly implements a system with an elitist/talented tenth philosophy 1920s the philosophy and practice shifts from elitist to progressive 1923-1933 adult illiteracy drops from more than 70% to approximately 50% By 1950s adult illiteracy drops to 28% where it stagnates until 1960s 1950s-1980s enrollment rates expanded faster than population growth By 1980 just 13% of Panamanians over age 10 were illiterate By 1980 there is no significant gender gap in literacy nor enrollment rates By the mid-1980s primary enrollment rates were at 113%, secondary almost 66% and university enrollment for persons aged 20-24 approximately 20% “growth in enrollment was accompanied by a concomitant (if not always adequate) expansion in school facilities and increase in teaching staff” (Meditz & Hanratty, 1987, Education section) By 2009 reported illiteracy rates were down to 7% (CIA, 2010; EFA, 2010). Considering that history, the other information in this paper, and my observations, experiences and knowledge, Panama gets high marks in a number of areas, including teacher-student ratio, public expenditure, improvements in enrollment and literacy rates, equitable treatment and achievement regardless of gender, religion, ability, sexual preference, and most ethnicities/races. In addition, despite the recent Kuna kidnapping incident and some complaints, the facilities are usually adequate and functional, as Meditz and Hanratty (1987) acknowledge and my own observations corroborate. The Path Between the Seas and Bridge to the Americas: The Trail Ahead/Setting Sail La Educación inclusiva se centra en todo el alumnado, prestando especial atención a aquellos que tradicionalmente han sido excluidos de las oportunidades educativas, tales como alumnos(as) con necesidades especiales y discapacidades,niños(as) pertenecientes a minorías étnicas y lingüísticas, y otros. Tr. Inclusion focuses on all students, paying particular attention to those who have traditionally been excluded from educational opportunities, such as students with special needs, disabled students, ethnic minorities, other language learners, and others. (from the “Plan Nacional de Educacion Inclusiva,” MEDUCA, 2010) EDUCATION IN PANAMA 24 Indeed, I think sometimes it’s easier--and more symbolically satisfying--to fix the buildings than it is to fix less tangible problems, such as the teaching methods and the school schedule. Can you imagine the kidnappers demanding more inquiry and critical thinking and less rote memorization? Yet that is what Panama needs. It needs changes to its pedagogy. In addition, the school schedule hinders learning: the days start too early, end too early and there are not enough days in the school year. Moreover, teacher salaries need to increase. As of 2009, k-12 teachers generally earned between $300 and $900 per month (M. Demaris & L. Fennario, personal communication, 2008). Like the US, teacher salaries increase based on longevity, highest degree earned, and recertification/ continuing education points. For a teacher to earn $900 per month they’d have to have been teaching for about 10 years, have at least a master’s degree and a whole lot of continuing education points. The low salaries may be partly to blame for behaviors such as leaving classrooms unattended. Reported literacy rates have improved, and UNESCO data on youth literacy rates--corroborated by my observations and communication with Price Peterson--suggest the trend of improvement will continue (UNESCO, 2010; P. Peterson, personal communication, April, 2010). Nonetheless, considering the analysis of the literacy data provided herein, Panama should adopt a stricter definition of literacy and develop a corresponding instrument to more accurately measure literacy. To avoid stormy weather, Panama needs to set a course that will correct for potentially devastating inequities, namely attrition of males and the gap in achievement for the indigenous population. As for the latter, efforts currently underway such as: the afore-mentioned after school program, Casa Esperanza; the attendance incentive program, Network of Opportunities; and literacy programs targeting rural districts, like Loco por Leer6, should have a narrowing effect on the achievement gap between the indigenous population and the rest. Whereas, the problem of male drop out rates may be more difficult to address and will probably require coordination of a variety of sectors. For example, the types and quantity of employment opportunities impact this: for the past ten years unskilled construction labor has been in demand, thus possibly providing incentive to young males to quit school. Nevertheless, the education system can take steps to do its part, such as, recruiting male teachers, tying sports team participation to academic achievement and establishing mentor programs. Many of these problems could be addressed through enhancement and continuation of the pilot PDS I founded in Panama in 2008. Indeed, the NCATE (2001) standards for professional development schools include EDUCATION IN PANAMA 25 utilizing the power of the university-school partnership to lobby for changes in policy, such as school schedules and teacher salaries (p. 5). More directly, I believe this model that partners university education programs with inservice teachers lays a foundation for positive change in pedagogy, curriculum delivery and learning. Conclusion Within the parameters of limiting space-time continuum constraints, this paper has attempted to give the reader a sense of the Panamanian education system, with particular attention to the social justice perspective. Thus, the inclusion of initial discussion of categories typically delineated for the purposes of examining social justice: gender, ability, sexual preference, race, and religion. Any subset of any of the number of topics covered in this brief overview could easily demand 10 times the text contained herein to attain a relatively thorough treatment. Topics such as teacher education and gender issues in Panama should be investigated separately and exhaustively. The disparities discussed, namely the urban/rural—majority/indigenous—achievement gap and the disparity in female/male university graduation rates, pose threats to socio-political stability and economic development if they continue unabated. I believe teacher education is one key to addressing gaps and disparity in education, as well as performance and achievement. To remain true to the action aspect of my definition of social justice, I will continue to work toward the implementation of an effective teacher education program in the model of professional development schools as described by NCATE (2001). To that end, a group of us here at George Mason University are currently working to develop and implement a model for an International PDS with the following mission: The mission of the International Professional Development School (IPDS) Collaborative for 2010 is to: Develop a model for a Professional Development School research-based on best practices, designed for implementation in Latin-America, with Panama as the first nation of implementation. To this end, members of the IPDS will explore, compare and evaluate best practices in PDSs, as well as subject areas and methods. In addition, partnerships will be solidified with universities and professionals in Panama in order to develop the model and assess current needs. The UN EFA goals will provide base-line guidance for the method and content of the program. Thus, implementation of the first IPDS in Panama will impact attainment of the EFA goals by 2015. EDUCATION IN PANAMA 26 References Benjamin, A. T. (2006). Mala nota para la educación. Martes Financiero, 452, November 21. Bloom, B. (1956). Bloom’s taxonomy. Retrieved from http://www.officeport.com/edu/blooms.htm . Central Intelligence Agency. (2010). Central America and Caribbean: Panama. The world factbook. Retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/pm.html . The EFA Global Monitoring Report Team. (2005). Education for all: Global monitoring report 2006. Paris, France: UNESCO. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/en/efareport/ . The EFA Global Monitoring Report Team. (2010). Education for all: Global monitoring report 2010. Paris, France: UNESCO. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/en/efareport/ . Focus (Eds.). (2006). Chiriqui. Focus: Panama 32, (1), 83-99. Focus (Eds.). (2006). The Central Provinces. Focus: Panama 32, (1), 113-115. Funk, I.K., Thomas, C., Vizetelly, F. H., Funk, C. E. (Eds.). (1949). New standard dictionary of the English language. New York, NY: Funk and Wagnalls. Gewirtz, S. (1998). Conceptualizing social justice in education: Mapping the territory. Journal of Education Policy, 13, (4), 469-484. Green, E. (2008). Can good teaching be learned? The New York Times Magazine, March 7, pp. 30-46. Greene, G. (1984). Getting to know the general: The story of an involvement. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. Harris, G. & St. Malo, G. A. (1993). The Panamanian problem: How the Reagan and Bush administrations dealt with the Noriega regime. Americas Group. Jackson, E. (2007). Rash of child deaths in one district of the Ngobe - Bugle Comarca. The Panama News, 13 (19). Retrieved from http://www.thepanamanews.com/pn/v_13/issue_19/news_01.html . LLECE. (2008). Student achievement in Latin America and the Caribbean: Results of the second regional comparative and explanatory study. Santiago, Chile: OREALC/UNESCO. EDUCATION IN PANAMA 27 References MEDUCA (2010). Plan nacional de educacion inclusiva: Compilación de las obras “educación inclusiva para atender a la diversidad” y “orientaciones pedagógicas.” Retrieved from http://www.meduca.gob.pa/ . MEDUCA (2007). Guia didactica de educacion ambiental (6th Edition). Retrieved from http://www.meduca.gob.pa/ . MEDUCA (1999) Estándares De Contenido y Desempeño. Retrieved from http://www.oei.es/estandares/panama.htm . McCullough, D. (1977). The path between the seas: The creation of the Panama Canal, 18701914. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. Meditz, S. W., & Hanratty, D. M., (Eds.) (1987). Panama: A country study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress. Retrieved from http://countrystudies.us/panama/21.htm . Molina, U. C. (2008). Educacion, estancada hace 11 anos. La Prensa, August 28. Muller-Schwarze, N. K.(2008) When the rivers run backwards: Field studies and statistical analyses of campesino identity in northern Cocle province, Republic of Panama, in the face of the Panama canal expansion (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from PsycINFO. (Accession # 2008-99190-372.) NCATE. (2001). Standards for professional development schools. Retrieved from http://www.ncate.org/documents/pdsStandards.pdf . Pan American Health Organization (1998). Panama. Health in the Americas, Vol. II. 391-400. Washington, DC: World Health Organization. Perkins, J. (2004). Confessions of an economic hitman. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Pub. Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. New York, NY: Anchor Books. Stromquist, N. P. (1996). Gender delusions and exclusions in the democratization of schooling in Latin America. Comparative Education Review, 40, (4), 404-425. UNICEF. (2010). At a glance: Panama. Retrieved from http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/panama_statistics.html#68 . EDUCATION IN PANAMA 28 References Winner, D. (2009). Kuna Indians released kidnapped MEDUCA regional director. PanamaGuide.com, July 29. (Original version published in Spanish in El Siglo by Chris Yee, 2009). Retrieved from http://www.panama-guide.com/article.php/20090729124352887 . EDUCATION IN PANAMA 29 Appendix A Kuna Indians Released Kidnapped MEDUCA Regional Director Wednesday, July 29 2009 @ 12:43 PM EDT Contributed by: Don Winner Views: 1,335 By Chris Yee for El Siglo - Panama's Ministry of Education (MEDUCA) and the Kuna Indians reached an agreement. The members of the Kuna Yala community in Ustupu decided to release the Regional Director of Education, Flumensio Smith, after they reached an agreement with the Ministry of Education. At 8:00 pm yesterday evening, authorities from MEDUCA and the insurer responsible for the work being done at the school, remained in a meeting to establish dates when the repairs on the school will begin, according to a report released by the Minster of Education, Lucy Molinar. She stressed that repairs to the "Nelé Kantule" school have been pending for more than four years, but it was not until now that the insurance company responsible for the work finally answered the call. Molinar regrets that in Panama problems have to be settled in this way. Smith was deprived of his freedom on Monday, and the condition for his release was the repair the school which is in bad condition. (See Comments) Editor's Comment: Holy crap! How's that for a pissed-off community. Forget about closing a couple of roads (since there's no roads up there anyway.) We're taking that guy hostage until someone gets up here to fix this school. Now, get busy... What has been happening with these government contracts to fix schools is that the construction companies suck the 20% or so profit out of the contract early in the process, then they just abandon the work and let someone else clean up their mess. The administration of Martin Torrijos did an exceptionally poor job of tracking these guys down and making them pay, one way of the other. The insurance companies were left holding the bag, and they are now on the hook for literally millions of dollars in unfinished contracts. EDUCATION IN PANAMA 30 Footnotes 1 In citing Nash and Safa, Stromquist continues the stereotype without providing the evidence to back it up (p. 410). In addition, on p. 413 she makes all kinds of claims re. education and gender in Latin America with no supporting evidence, e.g. women are concentrated in a few fields of higher ed., “schools…reproduce gender ideologies” and on. 2 The CIA World Factbook is a bit generous on this point, stating that rainy season begins in May. Every year and decade differ a bit, but it’s generally accepted—and confirmed by my years there—that rains may begin in March and almost always by April. October is typically the rainiest month, and dry season may begin as early as mid-December. In addition, due to micro-climates, particularly around Volcan Baru, there are regional variations despite Panama’s small size. Certain of the “rainy season” months on the Pacific side may be dry season months on the Caribbean side. And there are areas in the lowlands, such as Chitre, that enjoy a longer dry season, whereas, areas in the cloud forest in Boquete get rains virtually 12 months out of the year. 3 The reported numbers of deaths became a point of contention. Initially, while local officials reported over 40, the Panamanian government claimed there were just 10. In personal communication with a Panamanian doctor, he told me there were more than 200. Moreover, he claimed deaths of Ngobe children in Comarca by influenza and common colds are not uncommon, and due to, in his opinion, the combination of lack of access to health care and lack of trust of modern medicine. 4 This section on literacy was largely extrapolated from the previous Global Issue paper on literacy in Panama. The information has been condensed and focused on two areas: the importance of literacy and the problem with the data. 5 Some of the literature used the term retention in the context of retention in the school system, that is, as an antonym for attrition. However, the term retention often refers to students who are held back or who experience interrupted schooling and thus are older than the norm for their grade level. To avoid confusion, the latter definition—students who are held back—is how I use retention in this paper. Attrition refers to drop out rates, as determined by the difference in enrollment rates from primary to secondary to tertiary education. EDUCATION IN PANAMA 31 Footnotes 6 For more information on Loco por Leer see the Global Issue paper.