The USA, 1919-41 Depth Study

advertisement

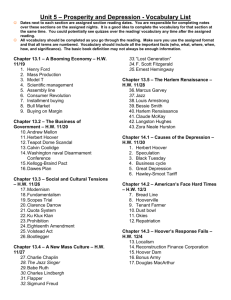

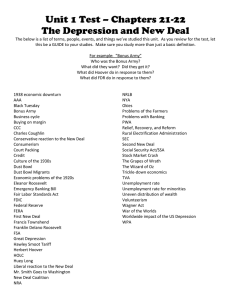

IGCSE: The USA, 1919-41 (Depth Study) What were the causes and consequences of the Wall Street Crash? Immediate and Systemic Causes •The stock market crash of 1929, which marked the beginning of the Great Depression of the United States, came directly from wild speculation which collapsed and brought the whole economy down with it. •The capitalist system is by its nature unsound, causing permanent depression for many and cyclical crises for almost all. •Clearly, those responsible for organizing the economy refused to recognize the causes and found reasons other than the failure of the system to explain the crash. •Herbert Hoover had said shortly before the crash: “We in America today are nearer to the final triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of any land.” •Henry Ford said the crisis was here because “the average man won’t really do a day’s work unless he is caught and cannot get out of it. There is plenty of work to do if people would do it.” A few weeks later, Ford laid off 75,000 workers. •Calvin Coolidge said: “When more and more people are thrown out of work, unemployment results. This country is not in good condition.” The Economy after the Crash •After the crash, the economy was stunned, barely moving. The stock market continued to plummet until it reached a low of 28 in 1932. •Over 5,000 banks closed and huge numbers of businesses, unable to get money, closed too. •Companies that stayed in business laid off employees and cut the wages of those who remained, again and again. By the end of 1930, half the 280,000 textile mill workers in New England were out of work. Ford Motor Company employed 128,000 workers in 1929 but only 37,000 in 1931. •Industrial production fell by 50 percent, and by 1933 about 15 million workers—a third of the labor force—were out of work. Run on the American Union Bank (New York, c. 1930) Hoovervilles •There were millions of tons of food around, but it was not profitable to transport it, to sell it. •Warehouses were full of clothing, but people could not afford it. Hooverville in Lower Manhattan (New York, 1932) •There were lots of houses, but they stayed empty because people couldn’t pay the rent, had been evicted, and now lived in shacks in quickly formed “Hoovervilles” built on garbage dumps. Seattle Hooverville resident Edwin Hall, repairing the roof of his shack, 1939. As people literally starved, they resorted to city garbage. Scenes like this one reported in a Chicago newspaper became commonplace: “Around the truck which was unloading garbage and other refuse, were about thirty-five men, women, and children. As soon as the truck pulled away from the pile, all of them started digging with sticks, some with their hands, grabbing bits of food and vegetables.” A survey in New York City in 1932 reported that 20 percent of the children were suffering from malnutrition. Children Soliciting Donations (c. 1931) When Russia asked Americans to apply for six thousand skilled jobs in 1931, it received a hundred thousand applicants. Beans, Bacon and Gravy (1931) I was born long ago in 1894, I've seen many a panic, I will own. I've been hungry; I’ve been cold. And now, I’m growing old, But the worst I’ve seen is 1931. Oh, those beans, bacon and gravy, They almost drive me crazy. I eat them till I see them in my dreams. When I wake up in the morning And another day is dawning, I know I’ll have another mess of beans. Well, we congregate each morning At the country barn at dawning, Every one is happy, so it seems. But when our day’s work is done, And we file in one by one, We thank the Lord for One more mess of beans. We’ve Hooverized on butter, And for milk, we’ve only water. And I haven’t seen a steak in many a day. As for pies, cakes and jellies, We substitute sow bellies, For which we work The country road each day. If there ever comes a time When I have more than a dime, They will have to put me Under lock and key, For they’ve had me broke so long, I can only sing this song Of the workers and their misery. —Pete Seeger Will Rogers Of Cherokee Indian descent, Will Rogers was a radio broadcaster and political commentator. His folksy humor and honest, intelligent observations about America earned the respect of the nation. Will Rogers “There is not an unemployed man in the country that hasn’t contributed to the wealth of every millionaire in America. The working classes didn’t bring this on, it was the big boys…. We’ve got more wheat, more corn, more food, more cotton, more money in the banks, more everything in the world than any nation that ever lived ever had, yet we are starving to death. We are the first nation in the history of the world to go to the poorhouse in an automobile.” —Will Rogers (1931) Peter J. Cornell “After vainly trying to get a stay of dispossession until January 15 from his apartment at 46 Hancock Street in Brooklyn, yesterday, Peter J. Cornell, 48 years old, a former roofing contractor out of work and penniless, fell dead in the arms of his wife. A doctor gave the cause of his death as heart disease, and the police said it had at least partly been caused by the bitter disappointment of a long day’s fruitless attempt to prevent himself and his family being put out on the street…. Cornell owed $5 in rent in arrears and $39 for January which his landlord required in advance. Failure to produce the money resulted in a dispossess order being served on the family yesterday and to take effect at the end of the week. After vainly seeking assistance elsewhere, he was told during the day by the Home Relief Bureau that it would have no funds with which to help him until January 15.” Bread Line in Brooklyn (New York, 1931) —The New York Times (1932). “You know my condition is bad. I used to get pension from the government and they stopped. It is now nearly seven months. I am out of work. I hope you will try to do something for me…. I have four children who are in need of clothes and food…. My daughter who is eight is very ill and not recovering. My rent is due two months and I am afraid of being put out” —Letter to Congressman Fiorello La Guardia (R-NY) from a tenement dweller on 113th Street, East Harlem, New York. Harlem (photograph by John Albok, 1930) “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” In 1932, Yip Harburg penned the lyrcis to the song which became the anthem of the Great Depression, “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” Harburg told Studs Terkel how he came to write the song: “I was walking along the street at that time, and you’d see the bread lines. The biggest one in New York City was owned by William Randolph Hearst. He had a big truck with several people on it, and big cauldrons of hot soup, bread. Fellows with burlap on their feet were lined up all around Columbus Circle, and went for blocks and blocks around the park, waiting…. In the song the man is really saying: I made an investment in this country. Where the hell are my dividends? It’s more than just a bit of pathos. It doesn’t reduce him to a beggar. It Bread Line, 6th Avenue makes him a dignified human, asking questions and 42nd Street —and a bit outraged, too, as he should be.” (New York, 1932) They used to tell me I was building a dream, And so I followed the mob, When there was earth to plow, or guns to bear, I was always there right on the job. They used to tell me I was building a dream, With peace and glory ahead, Why should I be standing in line, Just waiting for bread? Once I built a railroad, I made it run, made it race against time. Once I built a railroad; now it's done. Brother, can you spare a dime? Once I built a tower, up to the sun, brick, and rivet, and lime; Once I built a tower, now it's done. Brother, can you spare a dime? Once in khaki suits, gee we looked swell, full of that Yankee Doodly Dum, Half a million boots went slogging through Hell, and I was the kid with the drum! Say, don't you remember, they called me Al; it was Al all the time. Why don't you remember, I'm your pal? Buddy, can you spare a dime? The Dust Bowl To make matters worse for farmers, misguided mechanization, over-farming and drought in the central southern states turned millions of acres into a dust bowl and drove farmers off their land. Many of these ruined farmers headed to California looking for laboring work, where they were met with hostility. The folk singer and songwriter Woody Guthrie, born in Oklahoma, composed many songs concerning the nation’s Dust Bowl refugees. A Dust Storm An AntiDust Bowl Refugee Billboard Woody Guthrie’s “Do Re Mi” Lots of folks back East, they say, is leavin’ home every day, Beatin’ the hot old dusty way to the California line. ‘Cross the desert sands they roll, getting’ out of that old dust bowl, They think they’re goin’ to a sugar bowl, but here’s what they find Now, the police at the port of entry say, “You’re number fourteen thousand for today.” Oh, if you ain’t got the do re mi, folks, you ain’t got the do re mi, Why, you better go back to beautiful Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Georgia, Tennessee. California is a garden of Eden, a paradise to live in or see; But believe it or not, you won’t find it so hot If you ain’t got the do re mi. You want to buy you a home or a farm, that can’t deal nobody harm, Or take your vacation by the mountains or sea. Don’t swap your old cow for a car, you better stay right where you are, Better take this little tip from me. ‘Cause I look through the want ads every day but the headlines on the papers always say… John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath (1939) In Oklahoma, the farmers found their farms sold under the auctioneer’s hammer, their farms turning to dust, the tractors coming in and taking over. John Steinbeck, in his novel of the depression, The Grapes of Wrath, describes what happened: “And the dispossessed, the migrants, flowed into California, two hundred and fifty thousand, and three hundred thousand. Behind them new tractors were going on the land and the tenants were being forced off. And new waves were on the way, new waves of the dispossessed and the homeless, hard, intent, and dangerous…. And a homeless hungry man, driving the road with his wife beside him and his thin children in the back seat, could look at the fallow fields which might produce food but not profit, and that man could know how a fallow field is a sin and the unused land a crime against the thin children…. And in the south he saw the golden oranges hanging on the trees; and guards with shotguns patrolling the lines so a man might not pick an orange for a thin child, oranges to be dumped if the price was low….” These people, as Steinbeck said, were becoming “dangerous.” TOM JOAD: “Well, maybe it’s like Casy said: ‘A fella’ ain’t got a soul of his own—just a little piece of a big soul, the one big soul that belongs to everybody.’ Then….” MA JOAD: “Then what, Tom?” TOM JOAD: “Then it don’t matter. I'll be all around in the dark. I'll be everywhere. Wherever you can look, wherever there's a fight so hungry people can eat, I'll be there. Wherever there's a cop beatin' up a guy, I'll be there. I'll be in the way guys yell when they're mad. I'll be in the way kids laugh when they're hungry and they know supper's ready, and when the people are eatin' the stuff they raise and livin' in the houses they build, I'll be there, too.” MA JOAD: “I don’t understand it, Tom.” TOM JOAD: “Well, me neither, Ma. It’s just somethin’ I’ve been thinkin’ about. Give me your hand, Ma.” The Grapes of Wrath (1940) Max Cichon “Throughout the middle west the tension between the farmers and authorities has been growing … as a result of tax and foreclosure sales. In many cases evictions have been prevented only by mass action on the part of the farmers. However, until the Cichon homestead near Elkhorn, Wisconsin, was besieged on December 6 by a host of deputy sheriffs armed with machine-guns, rifles, shotguns, and tear-gas bombs, there had been no actual violence. Max Cichon’s property was auctioned off at a foreclosure sale last August, but he refused to allow either the buyer or the authorities to approach his home. He held off unwelcome visitors with a shotgun. The sheriff called upon Cichon to submit peacefully. When he refused to do so, the sheriff ordered deputies to lay down a barrage of machine-gun and rifle fire … Cichon is now in jail in Elkhorn, and his wife and two children, who were with him in the house, are being cared for in the county hospital. Cichon is not a trouble-maker. He enjoys the confidence of his neighbors, who only recently elected him justice of the peace of the town of Sugar Creek. That a man of his standing and disposition should go to such lengths in defying the authorities is a clear warning that we may expect further trouble in the agricultural districts unless the farmers are soon helped.” —The Nation (1932) A force of 150 Cuyahoga County Sheriff’s deputies battle a “home defense” crowd of 5,000 to evict John and Sophie Sparenga of Cleveland (Ohio, 13 July 1933). Mauritz Hallgren’s Seeds of Revolt (1933) “England, Arkansas, January 3, 1931. The long drought that ruined hundreds of Arkansas farms last summer had a dramatic sequel late today when some 500 farmers, most of them white men and many of them armed, marched on the business section of this town…. Shouting that they must have food for themselves and their families, the invaders announced their intention to take it from the stores unless it were provided from some other source without cost.” “Detroit, July 9, 1931. An incipient riot by 500 unemployed men turned out of the city lodging house for lack of funds was quelled by police reserves in Cadillac Square tonight….” “Indiana Harbor, Indiana, August 5, 1931. Fifteen hundred jobless men stormed the plant of the Fruit Growers Express Company here, demanding that they be given jobs to keep from starving. The company’s answer was to call the city police, who routed the jobless with menacing clubs.” “Boston, November 10, 1931. Twenty persons were treated for injuries, three were hurt so seriously that they may die, and dozens of others were nursing wounds from flying bottles, lead pipe, and stones after clashes between striking longshoremen and Negro strikebreakers along the Charlestown-East Boston waterfront.” “Detroit, November 28, 1931. A mounted patrolman was hit on the head with a stone and unhorsed and one demonstrator was arrested during a disturbance in Grand Circus Park this morning when 2000 men and women met there in defiance of police orders.” “Chicago, April 1, 1932. Five hundred school children, most with haggard faces and in tattered clothes, paraded through Chicago’s downtown section to the Board of Education offices to demand that the school system provide them with food.” “Boston, June 3, 1932. Twenty-five hungry children raided a buffet lunch set up for Spanish War veterans during a Boston parade. Two automobile-loads of police were called to drive them away.” “New York, January 21, 1933. Several hundred jobless surrounded a restaurant just off Union Square today demanding they be fed without charge….” “Seattle, February 16, 1933. A two-day siege of the County-City Building, occupied by an army of about 5,000 unemployed, was ended early tonight, deputy sheriffs and police evicting the demonstrators after nearly two hours of efforts.” The Bonus Army The anger of the veteran of the First World War, now without work, his family hungry, led to the march of the Bonus Army to Washington in the spring and summer of 1932. War veterans, holding government bonus certificates which were due years in the future, demanded that Congress pay off on them now, when the money was desperately needed. And so they began to move to Washington from all over the country with wives and children or alone. They came in broken-down old autos, stealing rides on freight trains, or hitchhiking. They were miners from West Virginia, sheet metal workers from Columbus, Georgia, and unemployed Polish veterans from Chicago. One family—husband, wife, three-year-old boy—spent three months on freight trains coming from California. Chief Running Wolf, a jobless Mescalero Indian from New Mexico, showed up in full Indian dress, with bow and arrow. More than twenty thousand came. Most camped across the Potomac River from the Capitol on Anacostia Flats. “The men are sleeping in little leantos built out of old newspapers, cardboard boxes, packing crates, bits of tin or tarpaper roofing, every kind of cockeyed makeshift shelter from the rain scraped together out of the city dump” —John Dos Passos. “The US Bonus Army” British Pathé Newsreel (1932) Bonus Army encamped on the lawn of the Capitol (1932) In Congress, the bill to pay off on the bonus passed the House of Representatives but was defeated in the Senate, and some veterans, discouraged, left. Most stayed— some encamped in government buildings near the Capitol, the rest on Anacosta Flats. President Hoover ordered the army to evict the veterans. Four troops of cavalry, four companies of infantry, a machine gun squadron, and six tanks assembled near the White House. General Douglas MacArthur was in charge of the operation, Major Dwight Eisenhower his aide. George S. Patton was one of the officers. MacArthur led troops down Pennsylvania Avenue, used tear gas to clear veterans out of the old buildings, and set the buildings on fire. “Bonus Army ‘Routed’” British Pathé Newsreel (1932) Eviction of the Bonus Army (1932) Then the army moved across the bridge to Anacostia. Thousands of veterans, wives, children, began to run as the tear gas spread. The soldiers set fire to some of the huts, and soon the whole encampment was ablaze. When it was all over, two veterans had been shot to death, an eleven-week-old baby had died, an eight-year-old boy was partially blinded by gas, two police had fractured skulls, and a thousand veterans were injured by gas. Eviction of the Bonus Army (1932) President Hoover’s Inaction President Hoover believed that the economy of the United States had been pulled down in 1929 by the weakness of the European economy. He also believed in the self-correcting business cycle. He hesitated until 1931 to use the artificial power of the federal government to try to control a business cycle because to bring politics into the marketplace was to profane the sacred. He never said “prosperity was just around the corner,” but his assurances and his inaction implied good times were around the corner. Kemp Starrett, “Speaking of Unemployment” (Life, 12 September 1930) In 1914, England and Germany, the major European industrial nations, had implemented certain social services: pensions for the retired, unemployment compensation, and medical insurance. In the US, the implementation of national social services was impeded by the division of powers between the state governments and the federal government. Traditionally , relief was a local and state responsibility, and, while the efforts of city and state governments were woefully insufficient, Hoover refused to break with tradition. Instead, he encouraged private charity. With unemployment approaching 40 percent in most of the major cities, private charity as an alternative to government-provided social welfare proved utterly inadequate. The yearly Community Chest drives organized in towns and cities by business to provide private charity for the poor, the ill, and the elderly were little more than publicity schemes. A 1930 Community Chest Drive (Houston, Texas) Like many middle and upper class Americans, President Hoover held the puritanical belief that federal relief in the form of social services would corrupt the American character. People would no longer feel the spiritual pressure to become self-made successes; they would lose their ambition. In America, Hoover declared, “it is as if we set a race. We, through free and universal education, provide the training of the runners; we give to them an equal start; we provide in the government the umpire of fairness in the race. The winner is he who shows the greatest ability, and the greatest character.” By 1931, Hoover feared the capitalist system was threatened and hypocritically abandoned his principles, giving federal relief not to the impoverished lower class in desperate need but to the wealthy ruling class. Hoover asked Congress to create the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. The purpose of the RFC was to loan money to private corporations to keep them from collapsing. Otherwise, corporate failures might ruin the banks and the mortgage and lifeinsurance companies that had loaned them money, undermining the entire capitalist system. The 1932 Presidential Election The Democratic Party presidential candidate in 1932 was Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Born to an old, established family, FDR had not rebelled against its model of the relaxed gentleman. Satisfied with mediocre academic achievement at Harvard, he had participated fully in the social life of the college. When he became active in politics during the “progressive” years, his reform philosophy was close to the paternalism of English conservatives. He was so sure of his place in the social and economic order, and in the strength of that order, that he could contemplate the government of his class providing organized charity for the poor and dependent masses. Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt (1932) Hoover, the Republican, feared and distrusted the Democrat Roosevelt. The difference between Hoover and Roosevelt was as deep and as emotional as the difference between fundamentalist and liberal Protestants. Hoover was the fundamentalist capitalist and Roosevelt, the liberal. Roosevelt was willing to use political power in the marketplace without the sense of reluctance or agonized conscience that Hoover felt. During the 1932 campaign, however, Roosevelt and his advisers revealed no dramatic or radical plans to deal with the Great Depression. Instead, Roosevelt’s speeches criticized Hoover’s experiments as irresponsible. Hoover had raised the national debt from $16 billion to $19 billion, and Roosevelt said, “Let us have the courage to stop borrowing to meet continuing deficits.” Hoover had asked farmers to reduce their crops and livestock, and Roosevelt said that it is a “cruel joke” to advise “farmers to allow 20 percent of their wheat lands to lie idle, to plow up every third row of cotton, and shoot every tenth dairy cow.” At the same time, Roosevelt said, “the country needs and demands bold, persistent experimentation. It is common sense to take a method and try it. If it fails, admit it frankly, and try another. But above all, try something.” The Election Results The hard, hard times, the inaction of the government in helping, the action of the government in dispersing war veterans—all had their effect on the election of November 1932. Democratic party candidate Franklin D. Roosevelt defeated Herbert Hoover overwhelmingly, took office in the spring of 1933, and began a program of reform legislation which became famous as the “New Deal.” When a small veterans’ march took place early in his administration, Roosevelt greeted them and provided coffee; they met with one of his aides and went home. It was a sign of Roosevelt’s approach. Result of the 1932 Presidential Election “It’s His ‘Baby’ Now!” Review Questions • What was the Wall Street Crash and what were its financial, economic and social effects? The Wall Street Crash occurred in October 1929 when the speculative stock market bubble of the 1920s collapsed. Investors were financially ruined, and banks which had loaned money to investors failed when the loans could not be repaid. As the banks closed, businesses lost access to financing and laid off workers. As workers were laid off, demand for products fell, increasing lay offs, introducing a downward economic spiral. The links between the US economy and other national economies spread the Great Depression around the globe. The social effects were profound—the poor lived in shacks in Hoovervilles relying on the private charity of bread lines for survival. President Hoover and the Republicans in control of Congress refused to interfere with the business cycle, so the financial, economic and social effects of the Wall Street Crash did not abate. Social unrest grew as the poor became more desperate. • How far was speculation responsible for the Wall Street Crash? Speculation triggered the Wall Street Crash, but speculation was not the cause of the Wall Street Crash. Nor was speculation the cause of the Great Depression. Capitalism was responsible for the Wall Street Crash and for the Great Depression. At all times, capitalism creates permanent crises and depression for some and periodic crises and depression for nearly all people. The US economy of the 1920s was characterized by specific structural weaknesses which made the crash and the depression both predictable and inevitable. These weaknesses included an extreme income gap separating rich and poor, an extremely regressive taxation policy, unemployment, a depressed agricultural sector, high tariffs which weakened the ability of trading partners to repay loans, monopolistic corporate and banking structures, economic misinformation, and a consumption-led business strategy in an economy in which only the top ten percent of the population had income with which to consume resulting in a slump in the construction and consumer goods industries. On top of this, the US ruling class refused to recognize how their policies caused the crash. • What impact did the crash have on the economy? The crash brought the whole economy down. • What were the social consequences of the crash? One-third of the nation was unemployed, living in poverty, malnourished. Social unrest grew as business and government leaders refused to provide relief to the poor. • How did President Hoover react to the crash? President Hoover believed the Great Depression had been caused by the weakness of the European economy. He believed that politicians should not interfere with the self-correcting business cycle. He also believed that providing relief would harm the morality of Americans, and that social services were the responsibility of local and state governments. Hoover encouraged businesses not to lay off workers and not to cut wages. Hoover encouraged farmers to produce less to raise prices. But Hoover took no action until 1931 when he asked Congress to create the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to loan money to banks to preserve the capitalist system. Displaying an attitude that “prosperity was just around the corner,” Hoover did very little to react to the crash. • What issues were involved in the presidential election of 1932? Compare Hoover’s and Roosevelt’s platforms. The central issue of the presidential election was how to react to the Great Depression. Hoover was a fundamentalist who believed in not interfering with the marketplace. Roosevelt was a liberal who promised to experiment with government interventions in the marketplace to restore the economy. While Hoover’s platform was “prosperity is just around the corner,” Roosevelt’s platform was vague. Roosevelt did not offer any radical or specific programs to end the Great Depression. Rather, Roosevelt’s platform attacked Hoover’s actions as irresponsible. Hoover’s eviction of the Bonus Army rallied support for Roosevelt, who met with veterans after his electoral victory. • Why did Roosevelt win the election of 1932? The American voters perceived Hoover as a do-nothing president simply waiting for prosperity to arrive. Roosevelt represented a change. Roosevelt promised Americans a “New Deal.”