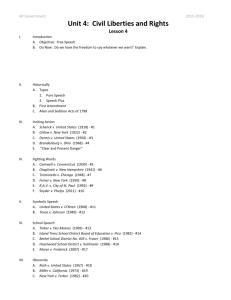

Chapter 2: The Legacy of Freedom / First Amendment

advertisement

Comm 407: The First Amendment The Legacy of Freedom 2500 years quest for freedom of speech From Athens to the First Amendment In Athens, the reforms of Solon in the 590s BC extended the right of citizens to express opinions The trend towards a liberal regime peaked in the age of Pericles in the 430s BC But even Athenians had certain limits on what they considered acceptable. The most famous example of this came when a popular jury found Socrates guilty of introducing false gods and corrupting the young and sentenced him to death. The Trial of Socrates, 399 BC Socrates speaks to jury at his trial: 'If you offered to let me off this time on condition I am not any longer to speak my mind... I should say to you, "Men of Athens, I shall obey the Gods rather than you."' The Romans The Roman Republic allowed a reasonable degree of free speech for its citizens. One advocate of free speech in the dying days of the republic was Cato the Younger, the chief political antagonist of Julius Caesar and the Triumvirate Cato’s name was to receive renewed reverence as the cause of freedom gathered support in the eighteenth century. Once the Roman republic had gone, tolerance of disloyal speech varied according to the identity of the emperor Gutenberg and printing press (1450s) “He created a whole new democratic world: he had invented the art of printing.” (Thomas Carlyle,1833) by 1500 there were in Europe at least nine million books, of thirty thousand titles, and over a thousand printers. 1516 Erasmus: 'In a free state, tongues too should be free.' English tradition of freedom With the invention of printing presses, a system of licensing and censorship was established. The first real progress in opposing censorship began in the seventeenth century, particularly with the Petition of Right (1627), which meant that, at least in theory, no person could be arrested solely for disagreeing with the government. The first recorded use of the expression “freedom of speech” can be found in Sir Edward Coke’s Institutes of the Laws of England (1628–44) English tradition of freedom At the height of the English Civil War in 1644 came the publication of one John Milton’s Areopagitica: an attack on an act the Parliamentarians had passed in 1643 sought to impose a new form of censorship. 'He who destroys a good book, kills reason itself.‘ ‘Let Truth and Falsehood grapple freely…’ 1689 Bill of Rights grants 'freedom of speech in Parliament' Tradition of Freedom of speech 1770 Voltaire writes in a letter: 'Monsieur l‘Abbé, I detest what you write, but I would give my life to make it possible for you to continue to write.' 1789 'The Declaration of the Rights of Man', a fundamental document of the French Revolution, provides for freedom of speech . 1791 The First Amendment of the US Bill of Rights guarantees four freedoms: of religion, speech, the press and the right to assemble. Tradition of Freedom of speech 1859 'On Liberty', an essay by the philosopher John Stuart Mill, argues for toleration and individuality. 1929 Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, of the US Supreme Court, outlines his belief in free speech: 'The principle of free thought is not free thought for those who agree with us but freedom for the thought we hate.' 1948 The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is adopted virtually unanimously by the UN General Assembly. Freedom of Speech Free speech is a means to an end: discovering the best idea possible. (social reasons) Free speech is also an end itself: the desire for free expression, self-fulfillment. (individualistic reasons) The Case for Free Speech Discovery of Truth: The pursuit of political truth through competition of ideas. A means of political participation. Check on Government: The restraint on tyranny, corruption, and ineptitude. Social Stability: The facilitation of majority rule. The marketplace theory ‘Let Truth and Falsehood grapple freely…’ Milton The best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market (Oliver Wendell Holmes) Freedom to think as you will and to speak as you think are means indispensable to the discovery and spread of political truth (Justice Louis Brandeis) Free expression and human dignity The First Amendment serves not only the needs of the polity but also those of the human spirit—a spirit that demands self-expression (Thurgood Marshall) Self-fulfillment Pleasure, Gratification Respect First Amendment (Bill of Rights ratified in 1791) Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof, or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances. The Bill of Rights originally applied only to federal government Barron v Baltimore (1833 case based on the Fifth Amendment): Chief Justice John Marshall: “The first ten amendments contain no expression indicating an intention to apply them to the State governments." Clear and Present Danger? The Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 (expired 1801) The Espionage Act of 1917 (applied mostly during war time) The Sedition Act of 1918 (repealed 1921) Japanese Internment Executive Order McCarthyism The Patriot Act? NSA Clear and Present Danger Test The question is whether the words used are of such nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent (Justice Holmes) Schenck v. United States 1919 Facts: During World War I, Schenck mailed circulars to draftees arguing that the draft was a monstrous wrong (but advised only peaceful action). Schenck was charged with conspiracy to violate the Espionage Act by attempting to cause insubordination in the military and to obstruct recruitment. Schenck v. United States 1919 Question: Are Schenck's words and actions protected by the First Amendment? Conclusion: Schenck is not protected in this situation. During wartime, utterances tolerable in peacetime can be punished. Abrams v. United States 1919 Facts of the Case The defendants printed and distributed leaflets denouncing the war and US efforts to impede the Russian Revolution. The defendants were convicted for inciting resistance to the war effort. They were sentenced to 20 years in prison. Abrams v. United States 1919 Question Presented Do the amendments to the Espionage Act or the application of those amendments in this case violate the free speech clause of the First Amendment? Abrams v. United States 1919 Conclusion: No and no. The act's amendments are constitutional and the defendants' convictions are affirmed. The leaflets are an appeal to violent revolution and an attempt to curtail production of munitions. Dissent: Holmes and Brandeis dissented on narrow ground: the necessary intent had not been shown. The First Amendment and the States States’ ‘espionage/sedition’ acts They were challenged based on the First Amendment. However, according to Barron v Baltimore (1833): “The first ten amendments contain no expression indicating an intention to apply them to the State governments." Gitlow v. New York (1925) Facts of the Case Gitlow, a socialist, was arrested for distributing copies of a "left-wing manifesto" that called for the establishment of socialism through strikes and class action of any form. Gitlow was convicted under a state criminal anarchy law, which punished advocating the overthrow of the government by force. Gitlow v. New York (1925) Question 1. Is the New York law punishing advocacy to overthrow the government by force an unconstitutional violation of the free speech clause of the First Amendment? Gitlow v. New York (1925) Conclusion Legal issue: Does the First Amendment apply to the states? Yes, by virtue of the liberty protected by due process that no state shall deny (14th Amendment). On the merits (facts): A state may forbid both speech and publication if they have a tendency to result in action dangerous to public security, even though such utterances create no clear and present danger. The rationale of the majority has sometimes been called the "dangerous tendency" test. Incorporation doctrine Gitlow’s decision was based on the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment (Incorporation Doctrine): No state shall… deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. All jurisdictions in the United States are required to respect freedom of speech The Smith Act of 1940 (The Alien Registration Act) The Act made it illegal for anyone in the United States to advocate, abet, or teach the desirability of overthrowing the government. The law also required all alien residents in the United States to file a comprehensive statement of their personal and occupational status and a record of their political beliefs. The Smith Act of 1940 (The Alien Registration Act) This statute was made the basis of a series of prosecutions against leaders of the Communist Party and the Socialist Workers Party. The constitutionality of the “advocacy” provision was upheld in Dennis v. United States (1951) The Court modified this position in Yates v. United States, (1957) construing “advocacy” to mean only urging that includes incitement to unlawful action. Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) Clarence Brandenburg was convicted of violating Ohio statute for advocating racial strife during a televised Ku Klux Klan rally. Did Ohio's criminal syndicalism law, prohibiting public speech that advocates various illegal activities, violate Brandenburg's right to free speech? Does a person have the right to advocate an illegal action? Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) The constitutional guarantees of free speech… do not permit a State to forbid advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to produce such action “Dangerous speech” test Previously “Bad tendency test”: “dangerous speech” exists if there is tendency to encourage or cause lawlessness After Brandenburg (incitement test): “dangerous speech” only if inciting or producing imminent lawless action Deciding what’s protected and what’s not Standard of judicial review: Minimum Scrutiny (Rational Standard) Strict Scrutiny (Compelling governmental interest) Strict Scrutiny The highest standard of judicial review. To pass strict scrutiny, the law or policy: 1. must be justified by a compelling governmental interest 2. must be narrowly tailored to achieve that goal or interest 3. must be the least restrictive means for achieving that interest