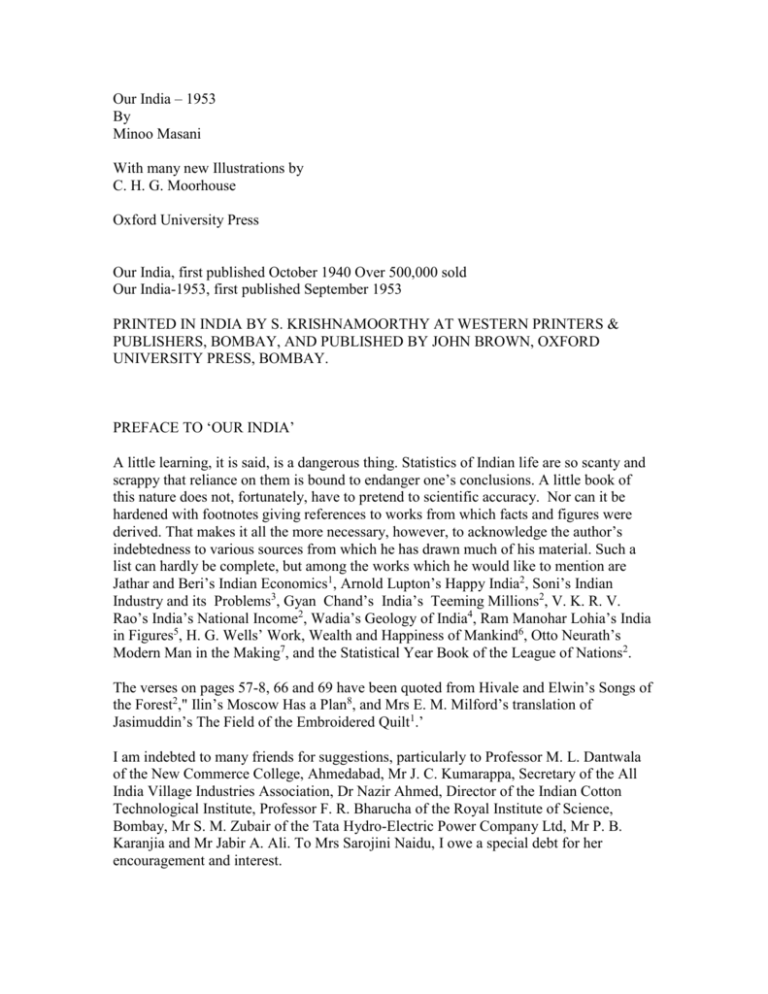

preface to 'our india'

advertisement