OVERVIEW OF THE COURSE - School of Social and Political Science

advertisement

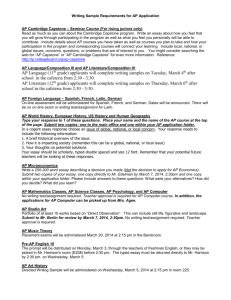

HISTORY OF MEDICINE 1 2012-13 Science, Technology and Innovation Studies School of Social and Political Science University of Edinburgh Old Surgeons’ Hall, High School Yards Edinburgh, EH1 1LZ History of Medicine 1 (SCSU08003) – 2011-12/Page 2 CONTENTS Overview of Course, Communication 3 Lecture times 3 Aims & Objectives 4 Assessment Procedures 5 On Writing Essays 7 Plagiarism 9 Referencing 10 Topics & Lectures 13 History of Medicine 1 (SCSU08003) – 2011-12/Page 3 OVERVIEW OF THE COURSE Course Organiser Steve Sturdy, Science, Technology and Innovation Studies Old Surgeons’ Hall, High School Yards, Edinburgh EH1 1LZ Email: s.sturdy@ed.ac.uk Tel: 0131 651 4741 Course Secretary Roisin O’Fee, School of Social & Political Science Undergraduate Teaching Office, Chrystal Macmillan Building 15a George Square, EH8 9LD Email: roisin.ofee@ed.ac.uk Tel: 0131 650 9975 COMMUNICATION While the course is running, all important information will be announced in lectures. Information and announcements will also be posted on Learn. As with your student SMS account; please get in the habit of checking Learn on a regular—and ideally, a daily—basis. If you have any queries about course administration, please email the Course Secretary, Roisin O’Fee, in the first instance. Questions about the course content should be directed to the Course Organiser, Steve Sturdy; you should either approach him after one of the lectures, or email s.sturdy@ed.ac.uk to arrange an appointment. The Course Organiser and the Course Secretary will endeavour to respond to queries as soon as possible, but be aware that replies to email enquiries may not be instant. The Learn site for this course includes a Discussion Board where you can post messages, questions or observations relevant to the course, and where the course lecturer and other students can read and respond to them. This is a useful way of raising practical questions that may be of interest to other members of the class – for instance if some aspect of the course administration is unclear to you. It is also a useful for raising questions about the academic content of the course, and for provoking discussions that fellow students’ may wish to contribute to, as well as staff. ABOUT THE COURSE History of Medicine 1 is a free-standing, 20-credit, level 1, half course run by the Science, Technology and Innovation Studies subject group of the School of Social and Political Sciences. It is available to all students studying in the College of Humanities and Social Science and in the College of Science and Engineering. LECTURE TIMES AND PLACE Weeks 1-10, Semester 2 Type Day Start End Area Lecture Monday 17:10 18:00 Appleton Tower, Lecture Theatre 4 Lecture Tuesday 17:10 18:00 Appleton Tower, Lecture Theatre 4 Lecture Thursday 17:10 18:00 Appleton Tower, Lecture Theatre 4 This course has no tutorials. History of Medicine 1 (SCSU08003) – 2011-12/Page 4 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES When seen in historical perspective, modern medicine – with its sophisticated technologies, its links to systematic scientific research, and its highly developed social organisation – is a remarkably recent development. And it is still changing, more rapidly than ever, both socially and intellectually. Understanding some of the factors that have shaped medicine in the past may also help us to think about how it might develop in the future. This course aims to provide a general introduction to the history of medicine from the ancient Greeks to the present day. It will examine some of the different ways that medical practitioners have thought about health and illness over the past two and a half thousand years. Special attention will be paid to the way that these different systems of knowledge, and the diagnostic and therapeutic practices associated with them, were adapted to the particular social and historical environments in which they developed and continue to develop. Students successfully completing the course will be expected to be able to: Discuss the changing nature and social organisation of health care and healing practices from the ancient world to the present day Discuss the dominant ideas about health and illness, their causes and treatment, that have prevailed in different historical periods Discuss how ideas about health and illness and the organisation of health care relate to the wider social and cultural context in which they are articulated Critically evaluate the use of historical evidence in historical argument COURSE REGULATIONS AND PROCEDURES The History of Medicine course is organised by the School of Social and Political Science. Make sure you consult the Social and Political Science Student Handbook as all the regulations detailed there apply to this course. This is available on Learn and also from the link below. http://www.sps.ed.ac.uk/undergrad/on_course_students/year_1_2 COURSE DELIVERY The course is taught by a combination of lectures and self-directed learning based on a list of required and recommended readings. Attending all lectures is essential. The lectures will provide you with a general framework – both chronological and interpretative – for understanding the development of medicine over the past two and a half thousand years. The reading material provides additional information – but more importantly, it will also deepen your understanding of the topics presented in the lectures. If you don’t attend the lectures, you will find it difficult to understand some of the arguments being developed in the readings. If you don’t do the readings, your understanding of the history of medicine will remain superficial. COURSE READINGS Most of the required readings are kept on reserve, and are available in the Main, Darwin, and James Clerk Maxwell Libraries. Note that the number of copies of the readings is limited, so do not leave preparation for your assignments until the last minute. Try to plan in advance and do the readings throughout the term. History of Medicine 1 (SCSU08003) – 2011-12/Page 5 ASSESSMENT PROCEDURES History of Medicine 1 will be assessed solely on the basis of two pieces of work. The first is a short multiple choice exam approximately midway through the semester (30% of the overall mark). This is an online examination, with a time limit. It will be explained in detail on Learn. The second is a final essay of approximately 2000 words, on a topic to be selected from a set list, which carries the remaining 70% of the overall mark. The list of essay topics will be posted on Learn early in the course. In order to pass the course, the long essay MUST be passed. The exam and essay must represent your own independent work. All sources used must be acknowledged and all quotations properly indicated. Treat this requirement with the utmost seriousness: failure to do so amounts to plagiarism. Plagiarism detection software is used to facilitate detection. See the plagiarism document for more information: http://www.docs.sasg.ed.ac.uk/AcademicServices/Discipline/PlagiarismStudentGuidance.pdf SUBMISSION OF ASSIGNMENTS DEADLINES: MULTIPLE CHOICE EXAM (30% of final mark) Deadline: 3.00 pm, Monday 25 February, 2013 LONG ESSAY (70% of final mark): 3.00 pm, Monday 22nd April 2013 AUGUST RE-SIT: 3.00 pm, Monday 05 August 2013 Written work must be uploaded via Learn AND a hard copy submitted to the HoM essay dropbox by the above deadlines. The dropbox is located in the main foyer of the Chrystal Macmillan Building, 15a George Square. Instructions will be given nearer the deadline. The electronic record of submission will be regarded as infallible. No claims by a student that they have submitted their essay will be entertained if there is no record of its submission on Learn. FOR EACH ESSAY, YOU NEED TO SUBMIT AN ELECTRONIC COPY AND ONE HARD COPY. BE AWARE THAT BOTH COPIES ARE SUBJECT TO THE SAME DEADLINE. LATE SUBMISSION/EXTENSIONS There are formal procedures for requesting an extension and penalties for late submission. The penalty will be a reduction of five marks per working day (i.e. excluding weekends) for up to five days. For work handed in more than five days late a mark of zero will be recorded. Check here for full details on submission penalties: http://www.sps.ed.ac.uk/undergrad/year_1_2/assessment_and_regs/coursework_requirements History of Medicine 1 (SCSU08003) – 2011-12/Page 6 If there is good reason for not meeting a coursework deadline, a student may request an extension from the Course Organiser, Steve Sturdy (and cc. Roisin O’Fee). Extension requests MUST be made and granted before the deadline, and must include supporting evidence: a good reason is illness, or serious personal circumstances, but NOT pressure of work or poor time management. If you think you will need a longer extension than 5 days, or your reasons are particularly complicated or of a personal nature, you should discuss the matter with your Personal Tutor (PT). N.B. There are NO late submissions for the final paper without express consent from the Course Organiser, which must be supported with documentation from your PT. RE-SIT Students whose work fails to meet the Pass standard in the June Diet are entitled to take the Resit essay in August 2013. Another long essay (c.2000 words) must be written to a different topic selected from a fresh list of topics posted on Learn shortly after 30 May 2013. This essay will be worth 100%. Your August Re-sit essay must be uploaded onto Learn and submitted in hard-copy to the HoM essay dropbox by 3pm, on Monday, 05 August, 2013. Students who fail twice in any given academic year can re-sit in August of the following year, without re-attending the course, always providing it is running in that year. Students should also be aware that course content may have changed somewhat in the intervening year. The onus is on the students to check this by contacting the Course Organiser well in advance of the August submission date. Students who fail twice in any given year may re-attend the whole course the following year, should they wish to do so, providing this has been approved by their PT/Academic Adviser. GRADES Grades on your first assessment will be returned with a provisional mark. This is meant to help you assess your progress toward the overall pass mark of 40%. The mark has to be provisional because final marks can only be determined after consultation with the External Examiner at the end of the course. The final mark represents the assessment of your overall performance. Usually provisional marks provide a good guide to your final mark, but you should know that sometimes the External Examiner may disagree with the provisional marks given out by the internal marker. Typically this will only lead to a change, up or down, of 2 or 3%. Occasionally, however, larger changes are made by the Board of Examiners. You must bear this in mind, so aim to give yourself a good safety margin. Final grade for the course: Official results are uploaded to MyEd by ACADEMIC REGISTRY, not the Unit. The marks given on Learn are a guide only as they are subject to change after consultation with the External Examiner after the Board of Examiners in June 2013. The external examiner for this course is Dr Ben Marsden, of the University of Aberdeen. History of Medicine 1 (SCSU08003) – 2011-12/Page 7 ASSESSMENT CRITERIA The following are the criteria according to which the assignment will be marked: a. b. c. d. Does the assignment address the question set, and with sufficient focus? Does the assignment show a grasp of the relevant concepts and knowledge? Does the assignment demonstrate a logical and effective pattern of argument? Does the assignment, if appropriate, support arguments with relevant, accurate and effective forms of evidence? e. Does the assignment demonstrate critical thinking in relation to arguments and evidence? f. Is the assignment adequately presented in terms of: correct referencing and quoting; spelling, grammar and style; layout and visual presentation? ON WRITING ESSAYS Some of you will already have a lot of experience of writing historical essays, but some of you will not. Here are some hints about how to go about it. History isn’t just about remembering dates Your essay should be an exercise in the writing of history, and that means you should not be satisfied with writing a chronicle of “one damned thing after another”. Historical writing is a creative attempt to reconstruct the past from the available evidence, in the most convincing manner possible. As well as describing the life and work of a past thinker, for example, you should also try to understand and explain why that thinker believed what they believed, why they did what they did, and why their contemporaries reacted to their work the way that they did. What makes history more interesting than a mere catalogue of facts is this endeavour to explain and understand. The importance of analysis Accordingly your essay should include a strong element of analysis, as well as description. So, if you were asked, for example, to assess the impact of Harvey’s discovery of the circulation of the blood on medical practice, it would not do simply to describe Harvey’s work, and then describe medical practice at that time. You need to consider the fact that medical practice is geared towards healing or ameliorating the condition of the patient. You then need to analyse how Harvey’s discovery might or might not have been seen as useful in that regard. You need to put yourself in the position of a medical practitioner of the midseventeenth century; the fact that from your twentieth-century perspective Harvey’s discovery is “scientifically correct” has nothing to do with the issue. Similarly, if you choose to write about the origins of the National Health Service, you should not be satisfied with saying that the origins were x, y, and z. Your analysis should explain whether x (and so on) was new, and if so how it had come about; and if x wasn’t new, why it was newly regarded as important when previous thinkers had not judged it important. When discussing the historical contributions of individual thinkers it is important to bear in mind that their achievements are never adequately explained by declaring them to be geniuses. If we wish to understand how and why Pasteur discovered the existence of microbes, it is no explanation to say he achieved this because everybody else was an idiot and he wasn’t. Similarly, it won’t do to say he was a genius and nobody else was. By the same token, it will not do to refer to “the Truth” for explanations either. It is no explanation to say that Ignaz Semmelweiss saw the Truth of the way things are, when others failed to see it. The onus is on an innovator to persuade their contemporaries of the truth of their innovation, but there is already a prevailing notion of what is “true” which the innovator has to show is not true. What people take to be true changes with history; the role of the History of Medicine 1 (SCSU08003) – 2011-12/Page 8 historian is to understand and explain why people held to the truths they thought were obvious and undeniable, and why and how such convictions change. Finally, you are bound to be selective with regard to what you include in your essay – so you should always show what is the significance of the particular facts you choose to recount, and why you think they should be picked out as historically important. The general rule here should be that the things you choose to concentrate upon in your essay should be the most important for our historical understanding. Structure and Organisation You should try to put your argument across in the clearest possible terms. This means providing your essay with a clear structure that highlights the development of your thesis. It is often most helpful for the reader to have an introduction in which the main aim of the essay is stated, together with an outline of your argument and the stages it will go through in order to make your point. Having done that, you should try to stick to that outline as you proceed. Breaking the essay into separate parts with sub-headings is probably the clearest way of guiding the reader but it is not essential. You should end your essay with a conclusion which “hammers home” your argument – do not throw in anything new at this stage – and brings together the different elements of your discussion. Your essay will be judged on how well you have marshalled the evidence to support your case. There are few answers in historical writing which can be said to be categorically “correct” or “incorrect”; all the historian can do is present more or less persuasive accounts of how it might have been. It follows that you do not necessarily have to agree with the lecturer, whose opinions may be based on selective reading of the evidence (almost certainly), ignorance of crucial counter-evidence (probably), or poor argumentation (heaven forbid!). A good essay will critically assess all the sources of evidence it considers, to arrive at a carefully argued conclusion. Clarity and style You may have a very clear idea of what you are trying to say when you write your essay – but the important thing is that the person who reads that essay knows what you are trying to say. A clear writing style is essential if you are to communicate effectively. When writing your papers, pay attention to spelling, punctuation and grammar. Bad English, and errors in spelling, punctuation and grammar, will be penalised by deduction of marks: you could lose up to 10% in this way. You will lose even more marks if the person marking your essay is not able to make sense of what you write. So take this warning seriously. Take pride in cultivating a good, clear style. And leave yourself time to read through a draft of your essay and edit it for clarity before submitting it. Using sources Academic writing is all about presenting and analysing evidence. But you also need to tell your readers where that evidence came from – otherwise they might think that you are just making it up! It is therefore important that you cite the sources you use when you write your essay. Never 'lift' passages - even as little as a sentence - from a book or article without putting them in quotation marks. Doing that is plagiarism, and may well result in a fail mark for your essay, however good it is otherwise. Either use quotation marks or put things in your own words. You should then cite the source. Referencing is crucial. The fundamental purpose of proper referencing is to provide the reader with a clear idea of where you obtained your information, quote, idea, etc. Lack of proper referencing will be penalised with the allocation of marks for essay(s). The quality of the sources you use is also important. You should avoid the use of nonacademic sources, especially from the Internet. Encyclopaedias, including Wikipedia, are not academic sources. Try to rely instead on the required and recommended readings provided in the Course Handbook and in the lectures. You may wish to read more widely and use other History of Medicine 1 (SCSU08003) – 2011-12/Page 9 sources – but if so, you must think critically about whether those sources are academically respectable and reliable. Academic journal articles, scholarly monographs and academic textbooks are generally reliable; popular books and journalism much less so. Remember, too, that in history of medicine as in any other field of research, what is taken to be the truth changes over time: a textbook or article from fifty years ago may include some useful information, but much of it may be out of date. So always think critically before you use a source. Learning and study skills The Study Development Team at the Institute for Academic Development (IAD) provides resources and workshops aimed at helping all students to enhance their learning skills and develop effective study techniques. Resources and workshops cover a range of topics, such as managing your own learning, reading, note making, essay and report writing, exam preparation and exam techniques. The study development resources are housed on 'LearnBetter' (undergraduate), part of Learn, the University's virtual learning environment. Follow the link from the IAD Study Development web page to enrol: www.ed.ac.uk/iad/undergraduates. Workshops are interactive: they will give you the chance to take part in activities, have discussions, exchange strategies, share ideas and ask questions. They are 90 minutes long and held on Wednesday afternoons at 1.30pm or 3.30pm. The schedule is available from the IAD Undergraduate web page (see above). Workshops are open to all undergraduates but you need to book in advance, using the MyEd booking system. Each workshop opens for booking 2 weeks before the date of the workshop itself. If you book and then cannot attend, please cancel in advance through MyEd so that another student can have your place. (To be fair to all students, anyone who persistently books on workshops and fails to attend may be barred from signing up for future events.) Study Development Advisors are also available for an individual consultation if you have specific questions about your own approach to studying, working more effectively, strategies for improving your learning and your academic work. Please note, however, that Study Development Advisors are not subject specialists so they cannot comment on the content of your work. They also do not check or proof read students' work. To make an appointment with a Study Development Advisor, email iad.study@ed.ac.uk (For support with English Language, you should contact the English Language Teaching Centre.) PLAGIARISM PREVENTION & DETECTION In the context of growing academic concerns about plagiarism throughout the Higher Education Sector, the School of Social and Political Studies now uses Turnitin plagiarism detection software to assist in the detection of plagiarism. TurnitinUK is an online service which searches the world wide web and extensive databases of reference material, as well as content previously submitted by other users. Each new submission is compared with all the existing information. Passages copied directly or very closely from existing sources will be identified by the software, and both the original and the potential copy will be displayed for the tutor to view. Where any direct quotations are relevant and appropriately referenced, the course tutor will be able to see this and will continue to consider the next highlighted case. For more information see: History of Medicine 1 (SCSU08003) – 2011-12/Page 10 http://www.docs.sasg.ed.ac.uk/AcademicServices/Discipline/PlagiarismStudentGuidance.pdf A GUIDE TO REFERENCING Several styles of formatting your bibliography are available and most important is to be consistent. The Harvard system is a standard very accepted within academia. The following instructions explain how it works. 1. After you have quoted from or referred to a particular text in your essay, add in parentheses the author’s name, the publication date and page numbers. Place the full reference in your bibliography. Here is an example of a quoted passage and its proper citation: Quotation in essay: ‘A strictly binary view of either aetiology (localism vs. contagionism) or prophylaxis (sanitationism vs. quarantinism) would, however, be a distortion’ (Baldwin, 1999:7). Book entry in bibliography: Baldwin, P. 1999, Contagion and the State in Europe, 1830-1930. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Note the sequence: author, year of publication, title, edition or translation information if needed, place of publication, publisher. 2. If you are employing someone else’s arguments, ideas or categorization, you will need to cite them even if you are not using a direct quote. One simple way to do so is as follows: ‘Arnold (1988:92) argues that more than imposed colonial medicine was a process of negotiation.’ Note that even in this case, one should provide a page number! 3. Your sources may well include journal or newspaper articles, book chapters, and internet sites. Below we show you how to cite these various sources. (i) Chapters in book: In your essay, cite the author of the chapter, e.g. (Pelling, 2002:36). In your bibliography details should be arranged in this sequence: author of chapter, year of publication, chapter title, editor(s) of book, title of book, place of publication, publisher, article or chapter pages. For example: Pelling, M. 2002. ‘Public and Private Dilemmas: The College of Physicians in Early Modern London’ in S. Sturdy. (ed.). Medicine, Health and the Public Sphere in Britain, 1600-2000. London: Routledge: 27-42. (ii) Journal article: In your essay, cite the author, e.g. (Crozier, 2000:357). In your bibliography, details should be in this sequence: author of journal article, year of publication, article title, journal title, journal volume, journal issue or number, article pages. History of Medicine 1 (SCSU08003) – 2011-12/Page 11 For example: Crozier, I. 2000. ‘Social Construction in a Cold Climate’ Social History of Medicine, 13 (3): 535-546. (iii) Newspaper or magazine article: If the article has an author, cite as normal in the text (Boseley, 2007:12). In the bibliography, cite as follows: Boseley, S. 2007 ‘Flu Jab May Not Work for Oldest Patients’ The Guardian, 25 Sept.: 12-3. If the article has no author, cite name of newspaper in text (The Herald) and list the source in the bibliography by magazine or newspaper title. For example: Sunday Times. 2005 ‘The Face of Things to Come’, 11 December: 14. (iv) Internet sites: When citing material from the internet, you should always indicated the date that you accessed it, as well as details of the location of that material. If you are citing an authored article from a website, cite by the name of the author, e.g. (Shiffman, 2007). In the bibliography, provide a full reference which should include author, date, title of website and URL address, plus the date you accessed it. For example: Shiffman, J. 2007 ‘Achieving the Maternal Health MDG: Momentum is Building but Political Challenges Remain’, http://blogs.cgdev.org/globalhealth/2007/10/achieving_the_matern.php [accessed 12 December 2012] If the article has no author, cite the name of the hosting website, e.g. (WHO, 2007). In the bibliography, provide a full reference including the publisher of the website, title of the article, the date published (if known), URL address, plus the date you accessed it , publisher or owner of the site. For example: WHO 2007 ‘Avian influenza – situation in Indonesia – update 23’, 05 November, http://www.who.int/csr/don/2007_11_05a/en/index.html [accessed 12 December 2012] SEXIST, RACIST AND DISABLIST LANGUAGE The language we use can often contain assumptions that the experiences of one group of people are the same for the whole of humanity, especially with regard to sex and race. The gist of our advice is that you should never use male nouns and pronouns when you are referring to people of both sexes (use a plural 'they', 'their' or think of a different way to phrase your argument; or for instance use 'he or she'). You should also never use language History of Medicine 1 (SCSU08003) – 2011-12/Page 12 that is racially derogatory or insulting towards people with disabilities or any other group. This does not mean that you have to stick to a narrow range of neutral views or opinions, but that your arguments have to be expressed in language that is both precise and objective. COURSE REPS Two course reps will also be appointed at an early stage in the course. Among their various responsibilities, they will be expected to be available to represent your views and opinions to the lecturer. If you wish to make your views felt, but prefer to do so anonymously, you should do so through the course reps. DISABLED STUDENTS The School welcomes students with disabilities (including those with specific learning difficulties such as dyslexia) and is working to make all its courses accessible. If you have special needs which may require adjustments to be made to ensure access to such settings as lectures, tutorials or exams, you should discuss these with your Director of Studies who will advise on the appropriate procedures. You can also contact the Student Disability Service, Third Floor, Main Library, George Square (telephone 650 6828) and an Advisor will be happy to meet with you. The Advisor can discuss possible adjustments and specific examination arrangements with you, assist you with an application for Disabled Students' Allowance, give you information about available technology and personal assistance such as note takers, proof readers or dyslexia tutors, and prepare a Learning Profile for your School which outlines recommended adjustments. You will be expected to provide the Disability Office with evidence of disability - either a letter from your GP or specialist, or evidence of specific learning difficulty. For dyslexia or dyspraxia this evidence must be a recent Chartered Educational Psychologist's assessment. If you do not have this, the Disability Office can put you in touch with an independent Educational Psychologist. WE LOOK FORWARD TO WORKING WITH ALL OF YOU AND HOPE YOU ENJOY THE COURSE. History of Medicine 1 (SCSU08003) – 2011-12/Page13 COURSE CONTENTS TOPIC 1: ANCIENT GREEK AND ROMAN MEDICINE Lecture 1: (14 January) General introduction to the course Lecture 2: (15 January) The emergence of medicine in the ancient Greek world Lecture 3: (17 January) Medical theory and practice in the ancient Greek world Lecture 4: (21 January) Medicine in the Roman world By the end of this topic, you should be able to answer the following questions: Who were the Hippocratic physicians? Why did the Hippocratics and other Greek physicians want to be regarded as philosophers? How did Greek philosophical medicine relate to religious healing? What was humoral theory? How did it explain health and illness? What did prognosis mean to a Greek physician and his patients? Why was it such an important skill? Who was Galen? Why did he have such an impact on medicine? What functions did Galen attribute to the blood and the heart? Required reading: Lawrence I. Conrad et al., The Western Medical Tradition, 800 BC to AD 1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), chaps 1 and 2 Further reading: G.E.R. Lloyd, “Introduction”, in Lloyd (ed.), Hippocratic Writings (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1973), pp. 9-60 Vivian Nutton, “Healers in the Medical Market Place: Towards a Social History of Graeco-Roman Medicine”, in Andrew Wear (ed.), Medicine in Society: Historical Essays (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), pp. 1558 (Attributed to) Hippocrates, On Airs, Waters and Places, trans. Henry Adams (e-text Library, University of Adelaide) [Read this to get a sense of how Hippocratic physicians understood the relationship between body and environment.] Ludwig Edelstein, “Hippocratic Prognosis”, idem, Ancient Medicine: Selected Papers of Ludwig Edelstein (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1967), pp. 6585 Ralph Jackson, “Physicians and their Medicine”, in idem, Doctors and Diseases in the Roman Empire (London: British Museum Press, 1988), pp. 56-85 M.T. May, “Introduction”, in Galen on the Usefulness of the Parts of the Body, trans. May (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1968), vol. I, pp. 3-64 [Gives a useful account of Galenic physiology of the heart and the blood.] Vivian Nutton, “Galen at the Bedside: The Methods of a Medical Detective”, in History of Medicine 1 (SCSU08003) – 2011-12/Page14 W.F. Bynum and Roy Porter (eds), Medicine and the Five Senses (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), pp. 7-16 TOPIC 2: MEDIEVAL TO RENAISSANCE MEDICINE Lecture 5: (22 January) Medicine in a Christian world Lecture 6: (24 January) Faith and charity: medieval hospitals Lecture 7: (28 January) Medical schools and the resurgence of learned medicine 29 January 2013 – no class Lecture 8: (31 January) The rediscovery of anatomy By the end of this topic, you should be able to answer the following questions: What did medieval Christians think was God’s role in healing? What did they think was the physician’s role? What did charity mean to medieval Christians? How was this expressed in the work of hospitals? What were the main orders of medical practitioner during the high Middle Ages? Why was medical practice organized in this way? What did medieval and Renaissance physicians think of the ancient medical writers? How did this influence the way that medicine was taught? Why did anatomy become such an important part of medicine during the Renaissance? Required reading: Nancy Siraisi, Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine: An Introduction to Knowledge and Practice (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), chaps 1-4 Lawrence I. Conrad et al., The Western Medical Tradition: 800 BC to AD 1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp. 264-92 Further reading: Katherine Park, “Medicine and Society in Medieval Europe, 500-1500”, in Andrew Wear (ed.), Medicine in Society: Historical Essays (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), pp. 59-90 Lawrence I. Conrad et al., The Western Medical Tradition: 800 BC to AD 1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), chaps 3-5 D.W. Amundsen, “Medicine and Faith in Early Christianity”, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 56 (1982), 46-92 John D. Thompson and Grace Goldin, The Hospital: A Social and Architectural History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1975), chap. 1 John Henderson, “The Hospitals of Late-Medieval and Renaissance Florence: A Preliminary Survey”, in Lindsay Granshaw and Roy Porter (eds), The Hospital in History (London: Routledge, 1989), pp. 63-92 History of Medicine 1 (SCSU08003) – 2011-12/Page15 Jerome J. Bylebyl, “The School of Padua: Humanistic Medicine in the Sixteenth Century”, in C. Webster (ed.), Health, Medicine and Mortality in the Sixteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979), pp. 335370 Andrew Cunningham, “Fabricius and the ‘Aristotle Project’ in Anatomical Teaching and Research at Padua”, in A. Wear, R.K. French and I.M. Lonie (eds), The Medical Renaissance of the Sixteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), pp. 195-222 [find in e-reserve] Jonathan Sawday, “Execution, Anatomy, and Infamy: Inside the Renaissance Anatomy Theatre”, in idem, The Body Emblazoned: Dissection and the Human Body in Renaissance Culture (London: Routledge, 1995), pp. 54-84 TOPIC 3: THE REFORMATION TO THE SCIENTIFIC REVOLUTION Lecture 9: (4 February) Harvey and the circulation of the blood Lecture 10: (5 February) The Reformation and medical radicalism Lecture 11: (7 February) Medicine and the new science By the end of this topic, you should be able to answer the following questions: How did William Harvey’s discovery of the circulation of the blood relate to the work of Galen and Aristotle? Why did learned physicians become objects of suspicion during the Reformation? What was Paracelsianism? How did it relate to learned medicine? What implications did the rise of the new science have for religious healing? What implications did the Reformation and the rise of the new science have for the professional authority of physicians? What criteria did eighteenthcentury patients use to judge their doctors? To what extent did the medical theories that gave rise to new ‘models of the body’ between 1600 and 1800 affect medical practice? Required reading: Lawrence I. Conrad et al., The Western Medical Tradition: 800 BC to AD 1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp. 325-340 [for Harvey on the circulation] Peter Elmer (ed.), The Healing Arts: Health, Disease and Society in Europe 15001800 (Manchester University Press, 2004), chaps 4, 5 and 7 Further reading: Peter Elmer and Ole Peter Grell (eds), Health, Diesase and Society in Europe 15001800: A Source Book (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004) Andrew Wear, “William Harvey and the ‘Way of the Anatomists’”, History of Science, 21 (1983), 223-249 Charles Webster, “Paracelsus Confronts the Saints: Miracles, Healing and the Secularization of Magic”, Social History of Medicine, 8 (1995), 403-421 Charles Webster, “Paracelsus: Medicine as Popular Protest”, in Ole Grell and History of Medicine 1 (SCSU08003) – 2011-12/Page16 Andrew Cunningham (eds), Medicine and the Reformation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), pp. 57-77. Lawrence I. Conrad et al., The Western Medical Tradition: 800 BC to AD 1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp. 340-361 Roy Porter, “The Patient in England c.1660-c.1800”, in Wear (ed.), Medicine in Society, pp. 91-118. Harold J. Cook, “Good Advice and Little Medicine: The Professional Authority of Early Modern English Physicians”, Journal of British Studies, 33 (1994), 131 John Henry, “Doctors and Healers: Popular Culture and the Medical Profession”, in Stephen Pumfrey, Paolo Rossi, and Maurice Slawinski (eds), Science, Culture and Popular Belief in Renaissance Europe (Manchester University Press, Manchester, 1991), pp. 191-221. TOPIC 4: EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY MEDICINE Lecture 12: (11 February) Medicine in the marketplace Lecture 13: (12 February) The growth of medical education Lecture 14: (14 February) The Edinburgh medical school 18-22 February 2013 INNOVATIVE LEARNING WEEK Lecture 15: (25 February) Hospitals and social order By the end of this topic, you should be able to answer the following questions: What kinds of practitioners made use of the new market for medical education in the eighteenth century? How did the nature of medical education change to accommodate their interests? How did the teaching of anatomy in Paris and Edinburgh during the eighteenth century compare to anatomy as studied in the Renaissance medical schools? What was a quack? How were quacks distinguished from orthodox practitioners in the eighteenth-century medical world? What was the social function of the new voluntary hospitals that were established during the eighteenth century? How did this differ from medieval hospitals? How did the growth of hospitals affect the relationship between physicians and surgeons? Required reading: Peter Elmer (ed.), The Healing Arts: Health, Disease and Society in Europe 15001800 (Manchester University Press, 2004), chap.13 Lawrence I. Conrad et al., The Western Medical Tradition: 800 BC to AD 1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), chap. 7 Further reading: History of Medicine 1 (SCSU08003) – 2011-12/Page17 Peter Elmer and Ole Peter Grell (eds), Health, Diesase and Society in Europe 15001800: A Source Book (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004) Thomas Neville Bonner, Becoming a Physician: Medical Education in Great Britain, France, Germany and the United States 1750-1945 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), chap. 2 Toby Gelfand, “The ‘Paris Manner’ of Dissection: Student Anatomical Dissection in Early Eighteenth-Century Paris”, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 46 (1972), 99-130 Susan Lawrence, “Entrepreneurs and Private Enterprise: The Development of Medical Lecturing in London, 1775-1820”, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 62 (1988), 171-192 Christopher Lawrence, “Alexander Monro Primus and the Edinburgh Manner of Anatomy”, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 62 (1988), 193-214 C.J. Lawrence, “Ornate Physicians and Learned Artisans”, in W.F. Bynum and Roy Porter (eds), William Hunter and the Eighteenth-Century Medical World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), pp. 153-176 Guenter B. Risse, “Cullen as Clinician; Organisation and Strategies of an Eighteenth Century Medical Practice”, in A. Doig et al. (eds), William Cullen and the Eighteenth Century Medical World (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1993), pp. 133-151 Michael Barfoot, “Brunonianism Under the Bed: An Alternative to University Medicine in Edinburgh in the 1780s”, in W.F. Bynum and Roy Porter (eds), Brunonianism in Britain and Europe, Medical History, Supplement No. 8 (1988), pp. 22-45 Roy Porter, “Before the Fringe: ‘Quackery’ and the Eighteenth-Century Medical Market”, in Roger Cooter (ed.), Studies in the History of Alternative Medicine (London: Macmillan, 1988), pp. 1-27 Roy Porter, “The Gift Relation: Philanthropy and Provincial Hospitals in Eighteenth-Century England”, in Granshaw and Porter (eds), The Hospital in History, pp. 149-178 Colin Jones, “The Social Functions of the Hospital in Eighteenth-Century France: The Case of the Hôtel-Dieu of Nîmes”, in idem, The Charitable Imperative: Hospitals and Nursing in Ancien Régime and Revolutionary France (London: Routledge, 1989), pp. 48-86 TOPIC 5: NINETEENTH-CENTURY MEDICINE: SCIENCE, PRACTICE AND PROFESSIONALISATION Lecture 16: (26 February) Hospital medicine and the Paris school Lecture 17: (28 February) The growth of surgery Lecture 18: (4 March) The birth of medical laboratories Lecture 19: (5 March) Medical science and clinical practice By the end of this topic, you should be able to answer the following questions: How did the French Revolution affect the relationship between physicians and surgeons? What consequences did this have for medical understandings of disease? Surgeons began to venture routinely into the abdomen from the 1860s onwards. What social, intellectual and technological developments helped to History of Medicine 1 (SCSU08003) – 2011-12/Page18 make this possible? Why did experimental physiology become an important part of medical education during the nineteenth century? How did late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century medical practitioners understand the relationship between laboratory science and medical practice? What sources of knowledge did they look to besides laboratory knowledge? Required reading: Deborah Brunton (ed.), Medicine Transformed: Health, Disease and Society in Europe 1800-1930 (Manchester University Press, 2004), chaps 1, 3, 4, 11 Further reading: Deborah Brunton (ed.), Health Disease and Society in Europe 1800-1930: A Source Book (Manchester University Press, 2004) W.F. Bynum et al., The Western Medical Tradition, 1800-2000 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), chaps 1 and 2 W.F. Bynum, Science and the Practice of Medicine in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), pp. 25-54, 92-117 Roy Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind (HarperCollinsPublishers, 1997), Chapter XVI: “Psychiatry”, pp. 493-524. L.S. Jacyna, "Au Lit des Malades: A.F. Chomel's Clinic at the Charité 1828-9", Medical History, 33 (1989), 420-449 Ornella Moscucci, The Science of Woman: Gynaecology and Gender in England, 1900-1929 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), pp. 134-164 Mary Poovey, "'Scenes of an Indelicate Character': The Medical 'Treatment' of Victorian Women", in Catherine Gallaher and Thomas Lacqueur (eds), The Making of the Modern Body: Sexuality and Society in the 19th Century (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987) Richard L. Kremer, "Building Institutes for Physiology in Prussia, 1836-1846: Contexts, Interests and Rhetoric", in Anrew Cunningham and Perry Williams (eds), The Laboratory Revolution in Medicine (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), pp. 72-109. William Coleman, "The Cognitive Basis of the Discipline: Claude Bernard on Physiology", Isis, 76 (1985), 49-70 John Harley Warner, "Therapeutic Explanation and the Edinburgh Bloodletting Controversy: Two Perspectives on the Medical Meaning of Science in the Mid-Nineteenth Century", Medical History, 24 (1980), 241-258. L.S. Jacyna, "The Laboratory and the Clinic: The Impact of Pathology on Surgical Diagnosis in the Glasgow Western Infirmary, 1875-1910", Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 62 (1988), 384-406 Christopher Lawrence, "Incommunicable Knowledge: Science, Technology and the Clinical Art in Britain, 1850-1914", Journal of Contemporary History, 20 (1985), 503-520 TOPIC 6: SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND MASS MEDICINE Lecture 20: (7 March) Public health and germ theory Lecture 21: (11 March) Surgery and the remaking of the hospital History of Medicine 1 (SCSU08003) – 2011-12/Page19 Lecture 22: (12 March) The growth of corporate medicine Lecture 23: (14 March) The pharmaceutical industry Lecture 24: (18 March) Technology and medical practice By the end of this topic, you should be able to answer the following questions: How did public health thinking differ from clinical medicine? Why and how were ideas about disease germs incorporated into public health practice during the late nineteenth century? Was the germ theory a necessary precondition for the conquest of surgical sepsis? What techniques besides antisepsis contributed to that conquest? How was the development of mass medical care different in Britain from the USA? In what ways was it similar? What was "ethical" marketing of pharmaceuticals? How did it relate to the growth of medical laboratories? Why is American medicine so much quicker to take up new technologies than British medicine? Required reading: Deborah Brunton (ed.), Medicine Transformed: Health, Disease and Society in Europe 1800-1930 (Manchester University Press, 2004), chaps 2, 7 and 9 Roger Cooter and John Pickstone (eds), Companion to Medicine in the Twentieth Century (London: Routledge, 2002), chaps 1, 10 and 12 Further reading: Deborah Brunton (ed.), Health Disease and Society in Europe 1800-1930: A Source Book (Manchester University Press, 2004) Elizabeth Fee and Dorothy Porter, “Public Health, Preventive Medicine and Professionalization: England and America in the Nineteenth Century”, in Wear (ed.), Medicine in Society, pp. 249-276 John V. Pickstone, “Dearth, Dirt and Fever Epidemics: Rewriting the History of British ‘Public Health’, 1780-1850”, in Terence Ranger and Paul Slack (eds), Epidemics and Ideas: Essays on the Historical Perception of Pestilence (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), pp. 125-148 Charles E. Rosenberg, “Florence Nightingale on Contagion: The Hospital as Moral Universe”, in idem, Explaining Epidemics and Other Studies in the History of Medicine (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), pp. 90-121 Christopher Lawrence and Richard Dixey, “Practising on Principle: Joseph Lister and the Germ Theories of Disease”, in Christopher Lawrence (ed.), Medical Theory, Surgical Practice: Studies in the History of Surgery (London: Routledge, 1992), pp. 153-215 Steve Sturdy and Roger Cooter, “Science, Scientific Management, and the Transformation of Medicine in Britain c.1870-1950”, History of Science, 36 (1998), 421-466 W.F. Bynum et al., The Western Medical Tradition, 1800-2000 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), chap. 3 Jane Lewis, “Providers, ‘Consumers’, the State and the Delivery of Health-care Services in Twentieth-century Britain”, in Wear (ed.), Medicine in Society, pp. 317-345 History of Medicine 1 (SCSU08003) – 2011-12/Page20 Stephen J. Kunitz, “Efficiency and Reform in the Financing and Organization of American Medicine in the Progressive Era”, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 55 (1981), 497-515 Daniel M. Fox, “The Consequences of Consensus: American Health Policy in the Twentieth Century”, Millbank Memorial Fund Quarterly/Health and Society, 64 (1986), 76-99 Charles Webster, “Conflict and Consensus: Explaining the British Health Service”, Twentieth Century British History, 1 (1990), 115-151 Martin Powell, “The Ghost of Health-Services Past: Comparing British Health Policy of the 1930s with the 1980s and 1990s”, International Journal of Health Services, 26 (1996), 253-268 Jonathan Liebenau, “Company Structure and Scientific Medicine”, in idem, Medical Science and Medical Industry: The Formation of the American Pharmaceutical Industry (London: Macmillan, 1987), pp. 30-47 Timothy Lenoir, “A Magic Bullet: Research for Profit and the Growth of Knowledge in Germany around 1900”, Minerva, 26 (1988), 66-88 Joel D. Howell, “Machines and Medicine: Technology Transforms the American Hospital”, in Diana Elizabeth Long and Janet Golden (eds), The American General Hospital: Communities and Social Contexts (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1989), pp. 109-134 [insert link to e-reserve] Audrey B. Davis, “Life Insurance and the Physical Examination: A Chapter in the Rise of American Medical Technology”, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 55 (1981), 392-406 TOPIC 7: THE POLITICS OF MODERN MEDICINE Lecture 25: (19 March) Eugenics and human experimentation Lecture 26: (21 March) Regulating medicines Lecture 27: (25 March) Patient power in medicine Lecture 28: (26 March) Medical ethics, medical politics Lecture 29: (28 March) Conclusion: Medicine and global citizenship By the end of this topic, you should be able to answer the following questions: What was the eugenics movement? What did it have to do with medicine? How did randomised control trials change the way that doctors evaluate the effects of medicines? Why did patients begin to challenge the authority of the medical profession? What impact has this had on how medicine is practised? When and why did ethics become such an important part of medicine? Required reading: Deborah Brunton (ed.), Medicine Transformed: Health, Disease and Society in Europe 1800-1930 (Manchester University Press, 2004), chap. 10 Roger Cooter and John Pickstone (eds), Companion to Medicine in the Twentieth Century (London: Routledge, 2002), chaps 5, 7, 8 and 44 History of Medicine 1 (SCSU08003) – 2011-12/Page21 Further reading: Deborah Brunton (ed.), Health Disease and Society in Europe 1800-1930: A Source Book (Manchester University Press, 2004) A.M. Lilienfeld, “‘Ceteris Paribus’: The Evolution of the Clinical Trial”, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 56 (1982), 1-18 Harry M. Marks, “Playing it Safe: The Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act of 1938”, in idem, The Progress of Experiment: Science and Therapeutic Reform in the United States, 1900-1990 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), pp. 71-97 Harry M. Marks, “Notes From the Underground: The Social Organization of Therapeutic Research”, in Russell C. Maulitz and Diana E. Long (eds), Grand Rounds: One Hundred Years of Internal Medicine (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1988), pp. 297-336 [insert link to ereserve] Marcia L. Meldrum, “‘Simple Methods’ and ‘Determined Contraceptors’: The Statistical Evaluation of Fertility Control, 1957-1968”, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 70 (1996), 266-295 Jeremy Noakes, “Nazism and Eugenics: The Background to the Nazi Sterilisation Law of 14 July 1933”, in R.J. Bullen, H. Pogge von Strandmann and A.B. Polonsky (eds), Ideas into Politics (London: Croom Helm, 1984), pp. 75-94 Susan Lederer, Subjected to Science: Human Experimentation in America Before the Second World War (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), chap. 5: “‘Your Dog and Your Baby’: The Continuing Campaign against Human Vivisection” Daniel J. Kevles, “From Eugenics to Genetic Manipulation”, in John Krige and Dominique Pestre (eds), Science in the Twentieth Century (Amsterdam: Harwood Academic, 1997), 301-318 Mike Saks, “From Quackery to Complementary Medicine: The Shifting Boundaries Between Orthodox and Unorthodox Medical Knowledge”, in S. Cant and U. Sharma (eds), Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Knowledge in Practice (London: Free Association Books, 1996), pp. 27-43 Steven Epstein, “Activism, Drug Regulation, and the Politics of Therapeutic Evaluation in the AIDS Era: A Case Study of ddC and the ‘Surrogate Markers’ Debate”, Social Studies of Science, 27 (1997), 691-726.