Google Adds Spice to a Mobile Stew

advertisement

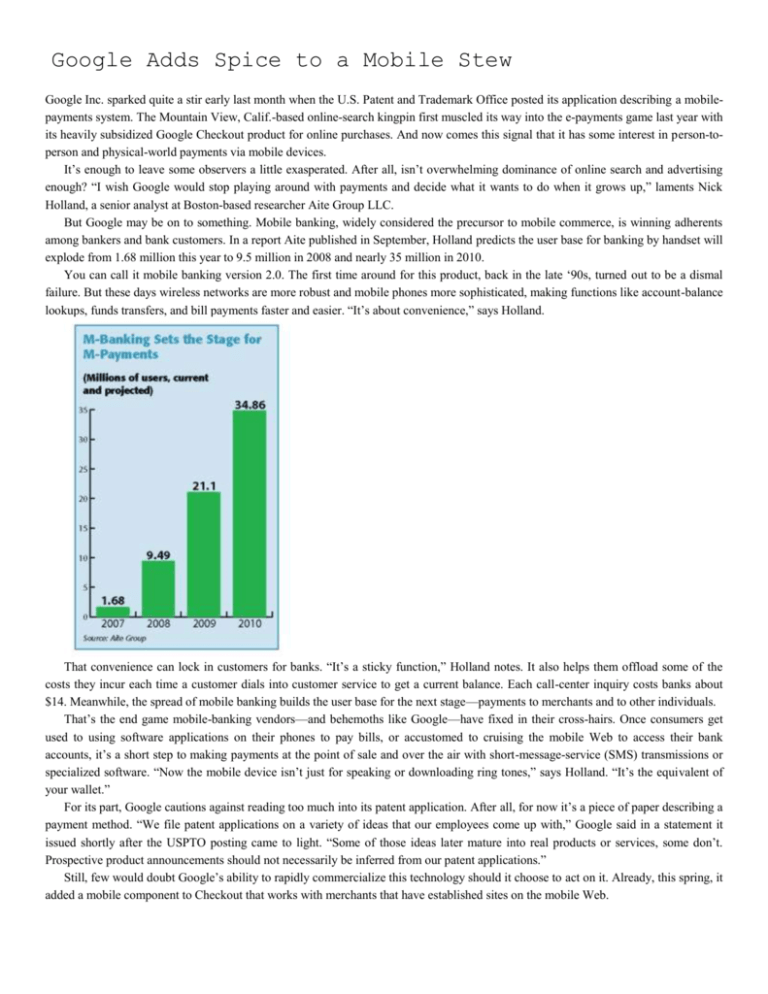

Google Adds Spice to a Mobile Stew Google Inc. sparked quite a stir early last month when the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office posted its application describing a mobilepayments system. The Mountain View, Calif.-based online-search kingpin first muscled its way into the e-payments game last year with its heavily subsidized Google Checkout product for online purchases. And now comes this signal that it has some interest in person-toperson and physical-world payments via mobile devices. It’s enough to leave some observers a little exasperated. After all, isn’t overwhelming dominance of online search and advertising enough? “I wish Google would stop playing around with payments and decide what it wants to do when it grows up,” laments Nick Holland, a senior analyst at Boston-based researcher Aite Group LLC. But Google may be on to something. Mobile banking, widely considered the precursor to mobile commerce, is winning adherents among bankers and bank customers. In a report Aite published in September, Holland predicts the user base for banking by handset will explode from 1.68 million this year to 9.5 million in 2008 and nearly 35 million in 2010. You can call it mobile banking version 2.0. The first time around for this product, back in the late ‘90s, turned out to be a dismal failure. But these days wireless networks are more robust and mobile phones more sophisticated, making functions like account-balance lookups, funds transfers, and bill payments faster and easier. “It’s about convenience,” says Holland. That convenience can lock in customers for banks. “It’s a sticky function,” Holland notes. It also helps them offload some of the costs they incur each time a customer dials into customer service to get a current balance. Each call-center inquiry costs banks about $14. Meanwhile, the spread of mobile banking builds the user base for the next stage—payments to merchants and to other individuals. That’s the end game mobile-banking vendors—and behemoths like Google—have fixed in their cross-hairs. Once consumers get used to using software applications on their phones to pay bills, or accustomed to cruising the mobile Web to access their bank accounts, it’s a short step to making payments at the point of sale and over the air with short-message-service (SMS) transmissions or specialized software. “Now the mobile device isn’t just for speaking or downloading ring tones,” says Holland. “It’s the equivalent of your wallet.” For its part, Google cautions against reading too much into its patent application. After all, for now it’s a piece of paper describing a payment method. “We file patent applications on a variety of ideas that our employees come up with,” Google said in a statement it issued shortly after the USPTO posting came to light. “Some of those ideas later mature into real products or services, some don’t. Prospective product announcements should not necessarily be inferred from our patent applications.” Still, few would doubt Google’s ability to rapidly commercialize this technology should it choose to act on it. Already, this spring, it added a mobile component to Checkout that works with merchants that have established sites on the mobile Web. The 18,000-word patent application describes a method of processing person-to-person and physical-world commerce transactions using text messages sent by mobile devices, specifying means by which payors and payees may be identified, whether accounts held at financial institutions may be involved, and how payors can put limits on transaction amounts or types of payees that may be paid. An identifier within the text message, which the application refers to as “gpay,” would trigger a payment. For example, a customer wanting to pay for a cup of coffee at a local store might tap out “gpay Starbucks357 3.50,” which identifies the store location in the Starbucks chain as well as the payment amount. Accounts from which funds may be drawn, according to the application, include demand-deposit accounts, credit and debit card accounts, and accounts users might hold with micropayment processors, which are typically prepaid accounts. No indication whether this service might incorporate the fledgling near-field communication (NFC) chips that allow mobile phones to act as if they were contactless cards. That could be just as well, for now. In this arena of mobile payments, the wheels of progress are grinding more slowly. While MasterCard Worldwide, Visa USA, and major banks like JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Citigroup Inc. have launched trials of handset-based contactless payment in the U.S. over the past 20 months, commercialization of the technology remains years away, according to ABI Research, an Oyster Bay, N.Y.-based researcher The primary problem right now is a tussle over security between the bank card networks and the wireless carriers, says ABI senior analyst Douglas McEuen, who follows the market for the semiconductors used in NFC. Financial institutions want security mechanisms to reside on NFC chipsets, which they regard as highly secure. Network operators argue they should be embedded in the SIM card, which they control and which identifies phone users to wireless systems. Without agreement, contactless payment based on NFC-equipped phones is likely to remain confined to pilots, McEuen says. And even when agreement is reached, he adds that further real-world trials will be required to test the agreed-upon model. “That’s going to slow things down further,” he says, noting such trials typically run 12 to 24 months. The upshot? ABI does not forecast commercial launches before 2012. A Campus Card That Could Earn an ‘A’ These days, with the risk of unmanageable debt hanging over the heads of young adults, the last thing parents want to send their kids to college with is a credit card. At the same time, debit cards are quite popular with this crowd. And, more popular than debit cards are mobile phones. So, with a little help from its merchant processor and an issuing bank, Slippery Rock University has reissued all of its student identification cards as prepaid debit cards, accompanied by radio-frequency tags that stick to a cell phone and allow it to access the same prepaid accounts. As of Sept. 10, about three weeks after classes started, the small-town campus north of Pittsburgh had issued about 9,000 Rock Dollars cards, some of them to faculty and staff. Some 24 merchants, most of them off-campus, are accepting the cards. Meanwhile, RFID readers have been installed at 300 vending, copier, and washing machines around the school to accept the tags. “We’re very satisfied with how this has rolled out,” says Barry Welsch, who’s managing the project for Heartland Payments Systems Inc. Princeton, N.J.-based Heartland, which is Slippery Rock’s acquirer, brought in its Debitek unit to help develop the reader technology, and Central National Bank of Enid, Okla., is issuing the cards and managing the accounts. The result is a payments program considered to be the first in the nation to rely on dual-function ID/payment cards as well as contactless tags users can attach to their cell phones. The Rock Dollars Program So Far (Data through Sept. 10) Live date: Aug. 24 (first student cards and tags issued) Transactions: 9,200 (Aug. 24-Sept. 10) Biggest day: 1,347 transactions (Sept. 4) Dollar volume: Close to $100,000 Average ticket: Close to $10 Merchants signed: 24 (21 off campus) POS terminals: 50 Self-service readers: 300 Source: Digital Transactions It’s also a program Heartland and Central National hope to use as a model to sell prepaid and contactless services to other schools. “Our idea [is] to sell this product on a national basis,” says Brud Baker, president and chief executive of the bank. “It’s single-service shopping. We do it all in one place.” The Slippery Rock accounts can be funded with grants and other aid issued to students as well as by the students and their parents using a Web site, terminals on campus, or a voice-response telephone system. Funds transfers are handled through the automated clearing house network. Technically, this is not a closed-loop system. The cards bear the logos of the Pulse and Star electronic-funds transfer networks. But most usage is on campus or with local merchants. While transactions are PIN-authenticated, the bank obtained permission from Star and Pulse to waive PIN entry for small-value card and tag transactions, Baker says. Heartland considered near-field communication, but the lack of NFC handsets was a problem. “We said, let’s put the tag on any phone and let the technology catch up,” says Heartland’s Welsch. Selling acceptance to nearby establishments isn’t hard, particularly now that students are back on campus, Welsch says. The cards work on existing terminals, and merchants pay a 1.5% fee per transaction, an amount Heartland rebates to the student cardholders. Students can pocket these fees or donate them to the university or a charity—a feature Welsch says is also selling acceptance. “We’ve chosen to rebate back to the students to drive more sales back to merchants who participate,” he says. Welsch and Baker hope this will be the start of something big. Heartland, which processes transactions for more than 300 colleges, has already been contacted not only by universities but also elementary schools, charities, and non-profits, such as libraries. “We’ve had more queries than we expected,” Welsch says. A Troubled ISO Starts Its Turnaround Independent sales organizations have largely overcome the unsavory reputation they gained in the late 1980s, when buccaneer salespeople quoted merchants one discount rate but charged another, or duped merchants into buying overpriced terminals. But occasionally, the old ghosts reappear. Such was the case in April, when the Federal Trade Commission accused Beaverton, Ore.-based Merchant Processing Inc., its then president and two sister companies of defrauding merchants, and had MPI placed in receivership. Nearly six months later, MPI’s new chief executive and his advisors say MPI is on the comeback trail, though they acknowledge the ISO will have to work hard to restore its reputation. “I think they’ll recover,” says Jamie Savant, a partner with Omaha-based merchantprocessing consultancy The Strawhecker Group, which MPI’s new bosses brought in to help with the turnaround. He adds, however, “I’m sure they’re going to lose a lot of merchants.” Since May, new chief executive James Keller, a certified public accountant with experience in turning around troubled companies, has implemented an overhaul of the sales staff and back-office support. He now plans to expand the firm’s presence into the Midwest. Most of MPI’s 5,000 merchants, which generate about $360 million in annualized charge volume, are on the West and East Coasts. A court-appointed receiver, Michael Grassmueck, hired Keller after the FTC filed a civil action April 11 in U.S. District Court in Portland, Ore., accusing MPI and its owner, Aaron Lee Rian, of deceptive business practices. MPI allegedly told merchants it would give them lower discount rates if they switched their processing to MPI. Many merchants, however, complained of being hit with surcharges and other fees they didn’t know about. MPI also allegedly induced merchants to sign four-year leases on terminals and promised to buy out their existing leases, but didn’t follow through and charged merchants high cancellation fees when they tried to exit their contracts. The FTC seeks a permanent injunction barring MPI’s previous business practices as well as refunds, court costs, and other “equitable relief,” according to its complaint. Washington State has sued the defendants, too. Rian’s lawyer, Portland attorney Stephen Feldman, won’t comment in detail, but says Rian denies the allegations. Besides implementing a house cleaning in the sales force, Keller says he’s embarked on improving customer service at MPI, which submits transactions through Atlanta-based Global Payments Inc. “One of the things [merchants] stressed was customer service was terrible, tech support was terrible,” Keller says. Without giving numbers, Keller says MPI’s merchant attrition was “high by industry standards” when the FTC moved in. Since then, however, he says, “I’ve been favorably impressed” with the changes. Robert Schroeder, the FTC’s assistant regional director in Seattle, says resolution of the court case could take a year or more unless there is a settlement. Being up-front with pricing is the key to good merchant relations, according to consultant Savant. “I just think agents and ISOs need to be prepared to disclose all fees to the merchants,” he says. “This particular group was not disclosing all the fees.”