What is blood pressure & pulse rate1

advertisement

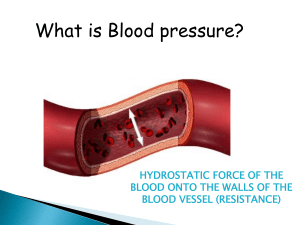

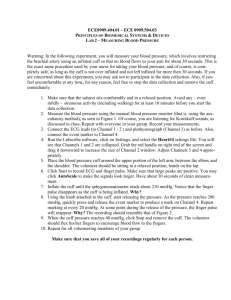

Measuring blood pressure & pulse rate All arteries carry blood away from the heart All veins carry blood to the heart Most arteries carry oxygenated blood Most veins carry de-oxygenated blood Veins have valves that prevent blood from flowing in the wrong direction Veins are wider than arteries Contraction of body muscles helps the blood flow through the veins Arteries have more elastic tissue and a thick muscular layer to cope with the high pressure of blood flow caused by the heart beat Capillaries transport blood from the arterioles to venules. They are microscopic vessels which are in most of our organs. They are one cell thick so they allow exchange of gas (O2;CO2); salts and water to occur between the capillaries and surrounding tissue. The pulse may be palpated at any place that allows an artery to be compressed against a bone. Pressure waves generated by the heart in systole moves against the arterial wall. The pulse can be used as a tactile guide to determine the systolic blood pressure (diastolic not palpable). The pulse pattern can be clinically significant, so it is important to note; 1. The rate in beats per minute. 2. The rhythm of pulse. • Fast • Slow • irregular 3. The strength of the pulse. 1. Absent 2. Barely palpable 3. Easily palpable 4. Full 5. bounding Your pulse varies depending on your age, level of fitness and how active you are being. A resting pulse is used in practice to record rate. The pulse rate needs to be taken over 1 full minute. The normal heart beat Terminology Slow pulse rate <60b/min = bradycardia Fast pulse rate >100b/min (resting) = tachycardia Irregular pulse – related to palpitations All these need to be referred to a healthcare professional as they indicate an underlying problem – ask the patient if they are aware of any problems When you document the rate also document the rhythm (e.g.regular or irregular) What else can affect the heart rate? Caffeine & alcohol – increases the strength and frequency of the heartbeat therefore increasing the rate Exercise increases the heart rate, but someone who exercises regularly may have a low resting rate. Disease affect the heart rate. Thyroid disease can either make the rate faster or slower depending type of disease. Drugs (medical & recreational) e.g. digoxin & bets blockers slow the HR. Recreational drugs tend to increase HR. • Count the heart beats for 60 seconds • It needs to be a resting pulse rate • Remember to check rate, rhythm & strength 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Temporal External maxillary (facial) Carotid Brachial Radial Femoral Popliteal Posterior tibial Dorsal pedis Blood Pressure What is blood pressure? Blood pressure refers to the force exerted by circulating blood on the walls of blood vessels. The pressure of the circulating blood decreases as blood moves through arteries, arterioles, capillaries, and veins. Blood pressure values are reported in millimetres of mercury (mmHg). Blood pressure is recorded as systolic over diastolic e.g. 120/60. What is blood pressure? (tap & hose) How is blood pressure controlled Short term control – ANS – barareceptors – vagus nerve. Intermediate control - Transcapillary shift – osmosis/plasma proteins. Long term control – Renin/angiotensin system; aldosterone. RAS System The systolic arterial pressure is defined as the peak pressure in the arteries, which occurs near the beginning of the cardiac cycle. The diastolic arterial pressure is the lowest pressure (at the resting phase of the cardiac cycle Measures of arterial pressure are not static, but undergo natural variations from one heartbeat to another and throughout the day. Blood pressure also changes in response to stress, nutritional factors, drugs, or disease. Systole is the contraction of heart chambers, driving blood out of the chambers. The chamber valves are closed. Diastole is the period of time when the heart fills with blood after systole (contraction). The chamber valves are open. The heart is at rest. High blood pressure (or hypertension) is defined in an adult as a blood pressure greater than or equal to 140 mm Hg systolic pressure or greater than or equal to 90 mm Hg diastolic pressure. High blood pressure directly increases the risk of coronary heart disease (which leads to heart attack) and stroke, especially when it's present with other risk factors. High blood pressure is the most important preventable cause of premature ill-health. Around 5.7 million people have hypertension which is undiagnosed. There is no universally accepted definition of hypotension (low blood pressure). Chronic disease have a lower target threshold e.g. diabetes; CKD. Risk factors for developing hypertension Obesity Physical inactivity High consumption of alcohol High intake of dietary sodium Low intake of dietary potassium Stress Increasing age Cigarette smoking Increased blood cholesterol Patients with systemic diseases including: Diabetes mellitus; renal disease; peripheral vascular disease Family history of hypertension, CHD or stroke Measuring blood pressure NICE clinical guideline 127; Quick reference guide; Aug 2011 HCP need adequate training and should have their performance reviewed periodically Devices for measuring BP must be properly validated, maintained and regularly recalibrated according to manufacturers instruction Ensure an appropriate cuff size for the patient’s arm is used Standardize the environment; relaxed temperate setting with the person quiet and seated with arm outstretched and supported Palpate the radial or brachial pulse before measuring BP Blood Pressure Measurement With Electronic Blood Pressure Monitors Points to note; If checking an electronic device against a mercury or aneroid sphygmomanometer the blood pressure may differ slightly between devices. It is good practice to occasionally check the monitor against a aneroid sphygmomanometer or another validated device. It is important to have a monitor calibrated according to manufacturer’s instruction. These devices should not be used for people with an irregular heart beat (Atrial Fibrilation) or heart rate lower than 50 beat/min Blood pressure measurement Estimation of blood pressure by auscultation (NICE clinical Guideline 34 Partial update of CG 18) Standardise the environment as much as possible: − relaxed temperate setting, with the patient seated − arm out-stretched, in line with mid-sternum, and supported. Correctly wrap a cuff containing an appropriately sized bladder around the upper arm and connect to a manometer. Cuffs should be marked to indicate the range of permissible arm circumferences; these marks should be easily seen when the cuff is being applied to an arm. Palpate the brachial pulse in the antecubital fossa of that arm. Rapidly inflate the cuff to 20 mmHg above the point where the brachial pulse disappears. Deflate the cuff and note the pressure at which the pulse re-appears: the approximate systolic pressure. Re-inflate the cuff to 20 mmHg above the point at which the brachial pulse disappears. Using one hand, place the stethoscope over the brachial artery ensuring complete skin contact with no clothing in between. Slowly deflate the cuff at 2–3 mmHg per second listening for Korotkoff sounds. Phase I: clear tapping sound (SBP) Phase II: Auscultatory gap: swishing sound or soft murmur Phase III: Loud slapping sound Phase IV: sudden muffling of sound Phase V: disappearance of sound (DBP) The first appearance of faint repetitive clear tapping sounds gradually increasing in intensity and lasting for at least two consecutive beats: note the systolic pressure. A brief period may follow when the sounds soften or ‘swish’. In some patients, the sounds may disappear altogether. The return of sharper sounds becoming crisper for a short time. The distinct, abrupt muffling of sounds, becoming soft and blowing in quality. The point at which all sounds disappear completely: note the diastolic pressure. When the sounds have disappeared, quickly deflate the cuff completely if repeating the measurement. When possible, take readings at the beginning and end of consultations. Hypertension; implementing NICE guidance. 2nd Ed march 2013 NICE CG127 Stage 1 hypertension: • Clinic blood pressure (BP) is 140/90 mmHg or higher and • ABPM or HBPM average is 135/85 mmHg or higher. Stage 2 hypertension: • Clinic BP 160/100 mmHg is or higher and • ABPM or HBPM daytime average is 150/95 mmHg or higher. Severe hypertension: • Clinic BP is 180 mmHg or higher or • Clinic diastolic BP is 110 mmHg or higher. White-coat effect: • A discrepancy of more than 20/10 mmHg between clinic and average daytime ABPM or average HBPM blood pressure measurements at the time of diagnosis Terminology high blood pressure = hypertension low blood pressure = hypotension fast pulse rate = tachycardia slow pulse rate = bradycardia Pediatrics. 2012 May;129(5):e1205-e1210. Epub 2012 Apr 16. Comparison of Mercury and Aneroid Blood Pressure Measurements in Youth. Shah AS, Dolan LM, D'Agostino RB Jr, Standiford D, Davis C, Testaverde L, Pihoker C, Daniels SR, Urbina EM; for the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study Group. Source Division of Endocrinology, ML 7012, Cincinnati Children's Hospital, 3333 Burnet Ave, Cincinnati, OH 45229. amy.shah@cchmc.org. Abstract OBJECTIVE: Because of concerns about the safety and environmental impact of mercury, aneroid sphygmomanometers have replaced mercury-filled devices for blood pressure (BP) measurements. Despite this change, few studies have compared BP measurements between the 2 devices. METHODS: The SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study conducted a comparison of aneroid and mercury devices among 193 youth with diabetes (48% boys, aged 12.9 ± 3.7 years; 89% type 1). Statistical analyses included estimating Pearson correlation coefficients, Bland-Altman plots, paired t tests, and fitting regression models, both overall and stratified by age (<10 vs ≥10-18 years). RESULTS: Mean mercury and aneroid systolic and diastolic BPs were highly correlated. For the entire group, there was no significant difference in mean systolic BP using the aneroid device, but there was a -1.53 ± 5.06 mm Hg difference in mean diastolic BP. When stratified by age, a lower diastolic BP (-1.78 ± 5.2 mm Hg) was seen in those ≥10 to 18 years using the aneroid device. No differences in systolic BP were observed, and there were no differences in BP by device in individuals <10 years. Regression analyses did not identify any explanatory variables. CONCLUSIONS: Although a small discrepancy between diastolic BP measurements from aneroid versus mercury devices exists, this variation is unlikely to be clinically significant, suggesting that either device could be used in research or clinical settings.