Cognition – 2/e Dr. . Daniel B. Willingham

advertisement

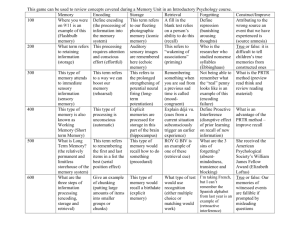

Cognition – 2/e Dr. Daniel B. Willingham Chapter 5: Memory Encoding PowerPoint by Glenn E. Meyer, Trinity University ©2004 Prentice Hall What Determines What We Encode in Memory? • • • • Factors that Help Memory: Emotion & Depth Factors that Don’t Help Memory: Intention to Learn and Repetition Problems with the Levels of Processing Theory Match Between Encoding and Retrieval: Transfer Appropriate Processing ©2004 Prentice Hall 2 Factors that Help Memory: Emotion and Depth • Laboratory Studies of Emotion and Memory - continued: • Cahill, et al. (1996) – PET analysis during recall of emotional or nonemotional film clips found • Emotional clips better recalled • Activity in amygdala correlated with recall. Amygdala suggested to modulate memory based on its evaluation of fear and disgust • • • Canli, et al. (2002) – women remember more emotional pictures than men and show more left amygdala activation Buchanan, et al. (2001) left amygdala more important than right in enhancing emotion effects on memory. Burke, et al. (1992) – slide show with surgical scenes better remember than one with scenes of auto repair. But result might be due to distinctiveness rather than emotion ©2004 Prentice Hall 3 Factors that Help - Continued • Flashbulb memories • • • Definition: A very rich, very detailed memory that is encoded when something that is emotionally intense happens. For example: Where were you when you heard of 9/11? The Kennedy assassination? The Challenger explosion? Brown and Kulik (1977) – first study of such, asked about Kennedy assassination. • Suggested flashbulb memories have three properties: • • • • • • Very complete Immune from forgetting Are accurate Due to a “NOW PRINT” process that takes a memorial snapshot of what is happening under great emotional duress. Modern thought is that there is NO special flashbulb memory system Shmolck, Buffalo and Squire (2000) studied OJ verdict memory and found that over time, memories do contain major distortions. Many details were reported, seemingly like a snapshot, but were incorrect. ©2004 Prentice Hall 4 Factors that Help - Continued • Depth of Processing • • Definition: A description of how one thinks about material at encoding. Depth refers to the degree of semantic involvement (that is, the word’s meaning). Craik and Lockhart (1972) – Levels of Processing framework • What is remembered based on depth of processing. The deeper the level the better the memory. Processing level can be: • • • • • Deep – greater degree of semantic involvement and thinking about such Shallow – thinking about the surface characteristics of the item Examples are seen in Table 5.1 from Craik and Tulving (1975) Craik and Tulving (1975) demonstrated that words are better remembered if processed more deeply according to their definitions of depth as seen in Table 5.1 and Figure 5.2 Notions similar to depth of processing: • • Elaborative rehearsal: A type of encoding in which new material is related to material one already knows - would aid memory Maintenance rehearsal: A type of encoding in which one repeats new material over and over to oneself . Not much of an aid to getting info into secondary memory according to research ©2004 Prentice Hall 5 Factors that Help - Continued • Depth and Elaboration • • • Elaborative processing does not always add to deep processing and better memory Elaboration has to be relevant to what you are trying to remember Bradshaw and Anderson (1982): • • • • • • Subjects heard sentence about a famous person Some then heard info relevant to original sentence Some heard info that was unrelated to original sentence. Folks who heard just original sentence had 38% recall, those who heard the irrelevant extra fact only had 32% recall. Folks who heard the extra relevant fact had 61% recall Thus, info must be relevant to aid in deep processing and memory performance. ©2004 Prentice Hall 6 Factors that Don’t Help Memory: Intention to Learn and Repetition • Intention to learn • • • Depth of processing studies indicate memory not affected by effort to learn as tested with incidental memory tests (subject not told they will be test on materials they are dealing with). Intentional memory test inform subjects that they will be tested. Hyde and Jenkins (1973) compared incidental and intentional memory by informing some subjects they would be tested on memory of items they were processing deeply or shallowly. As seen in Fig. 5.3, intention did not aid in performance. Only the shallow vs. deep variable was important. The latter aided performance. Repetition • • Nickerson and Adams (1979) as seen in Fig. 5.4 demonstrated that memory for the common Lincoln cent was quite bad even though it had been seen by most many, many times. Is Lincoln facing left or right? On which side is the date? Watkins (1973) demonstrated time an item in primary memory had little effect on LTM. ©2004 Prentice Hall 7 Problems with the Levels of Processing Theory 1) Concept of Deep Processing is Circular Circular theory A theory that uses term A to define term B but then also uses term B to define term A, leaving unclear what terms A and B mean. Critics claimed the only evidence for deep processing was better memory and better memory was due to deep processing – that is a circular argument 2) Level of Processing Theory said little about the importance of memory retrieval ©2004 Prentice Hall 8 Match Between Encoding and Retrieval: Transfer Appropriate Processing • Key Points: • • • Morris, et al. (1977): • • • • Must consider retrieval when discussing encoding This was a flaw of level of processing theories Varied encoding and retrieval by having subjects do either rhyming or semantic analysis on a sentence. The latter should induce more depth of processing. When tested with rhyming cues, the subjects in that group demonstrated a reversal of the depth effect as seen in Fig. 5.6. Indicates match between encoding and retrieval processes important as compared to standard “depth” explanation Hypothesis based on results: • • Transfer appropriate processing -The concept that when similar processes are used at encoding and retrieval times, retrieval will be more successful than if different processes were used Criticized as being circular – similar to depth of processing problems ©2004 Prentice Hall 9 What is Remembered and What is Forgotten – Brain Activity • Brewer, et al. (1998), Wagner et al. (1998) as seen in Box 5-2 • Subjects made judgments about pictures or words during an FMRI. • Then took a recognition test during FMRI • Findings: • Right dorsolateral prefrontal and bilateral parahippocampal cortex – more activity for items that would be remembered • Word targets – activity restricted to left parahippocampal cortex • Picture targets – bilateral activity in parahippocampal cortex ©2004 Prentice Hall 10 Why Do We Encode Information as We Do? • Prior Knowledge Reduces What We Must Remember • Prior Knowledge Guides the Interpretations of Details • Prior Knowledge Makes Unusual Things Stand Out ©2004 Prentice Hall 11 Prior Knowledge Reduces What We Must Remember • Use of Chunking Reduces Memory Load • • Chunk A unit of knowledge that can be decomposed into smaller units of knowledge. Similarly, smaller units of knowledge can be combined (“chunked”) into a single unit of knowledge (e.g., chunking the numbers 1, 9, 0, and 0 into a unit to represent the year 1900) Chase and Simon (1973) • • • Master level chess players and nonexperts viewed middle game of a chess board Master player memory of position far superior due to chunking of pieces into larger meaningful units using their expert knowledge Reingold, et al. (2001) – replicated results with a sophisticated eye movement tracking study ©2004 Prentice Hall 12 Prior Knowledge Guides the Interpretations of Details • • Prior knowledge can be thought of as a set of related facts Facts can come in a packet known as a schema (term introduced by Bartlett (1932)) which can guide memory processes: • Schema: A memory representation containing general information about an object or an event. It contains information representative of a type of event rather than of a single event • Default value: A characteristic that is a part of a schema that is assumed to be true in the absence of other information. For example, unless one is told otherwise, one assumes that a dog is furry; furriness is a default characteristic for dogs ©2004 Prentice Hall 13 Prior Knowledge Guides the Interpretations of Details - Continued • • Schemas aid in interpreting ambiguities . (Bransford and Johnson, 1972) had subjects try to recall the following: The procedure is actually quite simple. First you arrange things into different groups. Of course one pile may be sufficient depending on how much there is to do. If you have to go somewhere else due to lack of facilities that is the next step, otherwise you are pretty well set. It is important not to overdo things. That is, it is better to do too few things at one time than too many. In the short run this may not seem important but complications can easily arise. A mistake can be expensive as well. At first the whole procedure will seem complicated. Soon, however, it will become just another facet of life. It is difficult to foresee any end to the necessity for this task in the immediate future, but then one can never tell. After the procedure is completed one arranges the materials into different groups again. Then they can be put into their appropriate places. Eventually they will be used once more and the whole cycle will then have to be repeated. However, that is a part of life. • Memory was much improved if the subjects knew that the paragraph referred to “washing clothes” as that knowledge reduced the ambiguity of the paragraph. Similar results found by Anderson and Pritchard (1978) ©2004 Prentice Hall 14 Prior Knowledge Makes Unusual Things Stand out • Prior knowledge leads to expect what usually happens • Knowledge about common situations postulated to be organized into scripts (Schank and Abelson, 1977). • • Definition: Script - A type of schema that describes a series of events Example: • • • What to do in a restaurant Visiting the doctor Bower, et al. (1979) found good agreement among subjexts on basic scripts of American Culture as seen in Table 5.2 • Studies show that memory is best for details that are not part of the script and relevant to the goals of the script – Bower, et al. (1979) • Zachs, et al. (2001) – scripts used at retrieval and to understand ongoing behavior. ©2004 Prentice Hall 15