Chapter 10 Summary The unwritten character of the British

advertisement

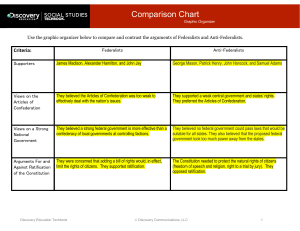

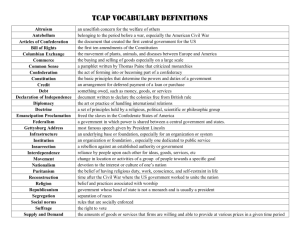

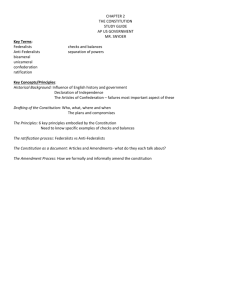

Chapter 10 Summary The unwritten character of the British constitution had been a big part of the problem that led to the Revolution. They guarded against creating a homegrown elite entrenched in public office by requiring that just about all state officials stand for election every year. Another anti-British resentment was reflected in the disestablishment of the Church of England in every colony where it had been the official church. Every state extended the franchise to more people than had enjoyed the right to vote under colonial law. Several southern states enacted laws indicating the hope that the institution’s days were numbered. The northern states went further; they abolished slavery or set in motion mechanisms by which slavery would gradually disappear. The collective affairs of the thirteen states were governed by the Articles of Confederation. Under the Articles, the United States was “a firm league of friendship.” The weakness of the Confederation Congress was consciously written into the Articles because the majority of the revolutionaries who approved it were hostile to powerful government. The Confederation Congress had its achievements. In January 1781, Virginia ceded the northern part of its claims to what would come to be called the national domain. Within a few years, all the states with western claims except Georgia followed suit. The Northwest Ordinances created procedures by which five future states would be carved from the “Northwest Territory.” Despite its achievements, disillusionment with the Confederation grew steadily. Finance was a tenacious problem thanks to petty politics. Britain refused to treat the United States as an equal power. Squabbles among the states invited foreign meddling. Alexander Hamilton and a few others, notably James Madison of Virginia, intended a bloodless coup d’état, peacefully replacing the Articles of Confederation with a completely new frame of government. Washington, Hamilton, and conservative men like them believed that disorders like the Shays Rebellion in Massachusetts were the inevitable consequence of weak government. The Constitutional Convention met in secret first to last. They finished in September 1787 whence most of the delegates scattered north and south to lobby for their states’ approval. The men who drew up the Constitution were conservatives in the classic meaning of the word. The government they created was, in John Adams’s word, “mixed,” a balance of the “democratical” principle (power in the hands of the many); the “aristocratical” (power in the hands of a few); and the “monocratical” (power in the hands of one). Under the Constitution, the balance shifted, with preponderant powers going to the federal government. The Constitution was to go into effect when conventions in nine states ratified it. The battle for ratification was between the federalists and anti-federalists. Among the anti-federalists were old patriots who feared that any centralized power was an invitation to tyranny. Madison, Hamilton, and John Jay took it upon themselves to answer critics in eighty-five essays later collected under the name the Federalist Papers. The Bill of Rights, the first ten amendments to the Constitution, was ratified in 1791 but tacitly agreed upon during the ratification process.