LNT Masters course show

advertisement

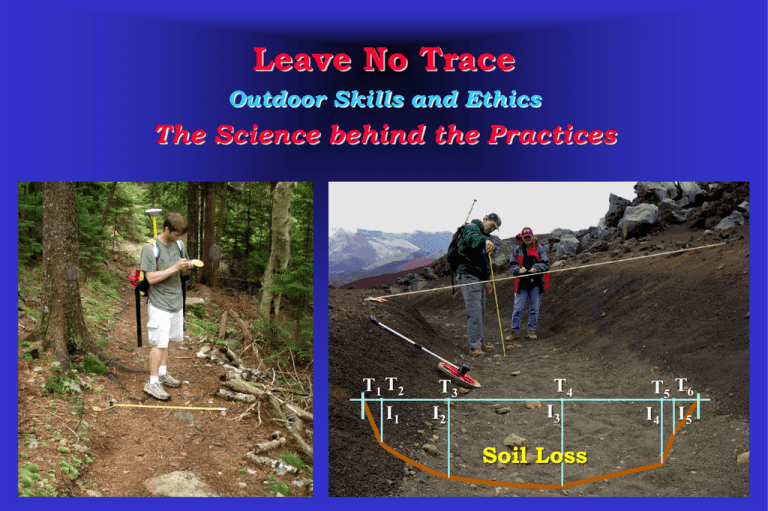

Leave No Trace Outdoor Skills and Ethics The Science behind the Practices T1 T2 I1 T3 I2 T4 I3 Soil Loss T5 T6 I4 I5 Presentation Objectives Describe recreation ecology research and how it helps inform the development of Leave No Trace practices. Highlight some of the more relevant research findings for each Leave No Trace principle. The LNT Message LNT practices are science-based: Recreation ecology research tells us about recreation impacts and the relative influence of use-related, environmental, and managerial factors. This information helps us to develop effective Leave No Trace practices. The LNT Message Social science research tells us about visitor attitudes, behaviors, social norms, and effective methods of communicating low impact practices. Haleakala National Park (Simulation - proliferation of informal trails) Informal (Visitor-Created) Trail Impacts Impact Indicators Park Zones Developed (11.7 ha) Threshold (16.2 ha) Natural (235.1 ha) 1509 1844 10,288 443 5532 5813 3880 3349 24,970 261 4335 5647 129 114 44 38 341 25 2571 1816 2427 589 784 971 Aggregate Length (m) Formal Trails Informal Trails Disturbance Area (m2) Formal Trails Informal Trails Lineal Extent (m/ha) Formal Trail Length Informal Trail Length Density (m2/ha) Formal Trails Informal Trails The Seven LNT Principles 1. Plan Ahead and Prepare 2. Travel and Camp on Durable Surfaces 3. Dispose of Waste Properly 4. Leave What You Find 5. Minimize Campfire Impacts 6. Respect Wildlife 7. Be Considerate of Other Visitors 1. Plan Ahead and Prepare Schedule your trip to avoid times/areas of high use. New campsites are often created on high use weekends. Even a few nights camping each year prevents their recovery. The potential for social impacts (e.g., crowding and conflict) is far greater during high use periods. 1. Plan Ahead and Prepare Schedule your trip to avoid times when resources are vulnerable. Vegetation and soils are far more susceptible to impact when wet. Wildlife are more sensitive to disturbance during mating, nesting/birthing, and winter seasons. 2. Travel and Camp on Durable Surfaces Experimental trampling studies reveal that trampling impacts can be avoided/minimized when you: Best: Stick to rock and naturally barren substrates, Best: Walk on the center of well-established trails or camp in the core barren portions of campsites, Good: Confine traffic to non-vegetated organic litter, OK: Confine traffic to dry grasses; avoid herbs. Resistance and Resilience: Forbs 1000 passes 0 passes 1 mo. later Forest forbs generally have low resistance and resilience. 250 passes Resistance and Resilience: Grasses 1000 passes 0 passes 1 mo. later Grasses generally have high resistance and resilience. 250 passes Vegetation Impacts Vegetation trampling Reduction in height Compositional change: Fragile to resistant Native to non-native Loss of vegetation cover Soil Impacts Trampling and pulverization of organic litter Loss of organic litter Compaction of soil: Increased runoff Decreased soil moisture Use-Impact Relationships: A Campsite Example Impact (%) 100 80 60 40 The majority of most types of impact occur at low use levels 20 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 Nights/Year Vegetation Loss Seedling Loss Soil Exposure Soil Density Litter Loss 70 Rationale for Dispersal & Containment Strategies The Use/Impact Relationship What are the implications of the curvilinear use/impact relationship for selecting a low-impact campsite? Amount of Use Rationale for Dispersal & Containment Strategies The Use/Impact Relationship a . Consider an area where camping is unregulated with 3 sites that receive 15 nights/yr . 15 Nights/Year Rationale for Dispersal & Containment Strategies The Use/Impact Relationship All permanent impact could be avoided if use from the 3 campsites could be dispersed to 45 sites, each with 1 night of camping/year. . 1 Management experience has shown this level of dispersal to be exceedingly difficult to achieve. Nights/Year Rationale for Dispersal & Containment Strategies The Use/Impact Relationship b a . . . 15 A containment policy is more effective. Use from 2 closed campsites is shifted to the 3rd. Cumulative impact is reduced from a (3 x a) amount of impact to a (1 x b) amount of impact. Nights/Year . 45 Impact Temporal Trends: Life-History of a Campsite or Trail 1 yr Time 10-30 yrs Impacts occur quickly; recovery can require up to 30 yrs. Implications: Use only well-established sites & trails; avoid lightly impacted sites/trails to promote their recovery. Traveling In popular areas: Stay on designated or wellestablished trails whenever possible. In pristine areas: Disperse traffic on the most resistant pristine surfaces if you must leave trails. Camping In popular areas: Stay on designated or wellestablished campsites. Restrict activities to the most highly disturbed areas. In pristine areas: Choose a pristine site with resistant surfaces. Disperse activities to avoid impact. 3. Dispose of Waste Properly Studies have shown bacteria to be present one year after cat-hole waste burial. Decomposition is aided by stirring the waste together with soil and water. Pathogens can effectively filtered from water moving through < 5 feet of medium-textured soils so cat-holes do effectively protect water resources. Desiccation, high temperatures, and UV radiation are lethal to pathogens but are highly effective only for thinly smeared surface-deposited waste. 3. Dispose of Waste Properly Recommendations: Use toilets, carry-out, or cat-hole wastes. Surface deposition is problematic due to aesthetics, animal and insect transmission of diseases, and the greater potential for water contamination. Burial (6-8”) in fine-textured soil >200 ft from water. Group latrines not recommended – the large mass of wastes would slow decomposition time. Snow – carry-out is the best option. 4. Leave What You Find Avoid introducing or transporting non-native species. Studies have surveyed hikers at trailheads and found numerous seeds on the clothing of hikers and in their gear. Clean your clothing, boots, and gear of seeds before you depart home. Many non-native plants remain in the vicinity of trails and campsites. However, a few highly invasive plants are able to out-compete native vegetation in undisturbed environments (e.g., Japanese stilt grass) Researchers have also germinated non-native seeds that have passed through the intestines of horses. 4. Leave What You Find Leave flowers for others to see. Picking them prevents formation of seeds vital to their reproduction and survival. A Great Smoky Mtn. NP study found significantly fewer orchids along trails in comparison to more distant areas. 5. Minimize Campfire Impacts Campfires can cause lasting impacts to the backcountry. Research shows that campfire-related impacts are both socially and ecologically significant. Campfire sites remind others that the area is not pristine, large mounds of charcoal with trash are an eyesore, firewood depletion can leave a human “browse line” and tree damage and stumps represent acts of depreciative behavior. Tree cutting removes dead trees important for cavitynesting wildlife. Firewood depletion diminishes nutrient cycling and soil macro-fauna. Campfires produce long-term changes in soil physical and chemical properties. 5. Minimize Campfire Impacts Avoid campfirerelated impacts by using a stove. A study of backcountry camping impacts at Great Smoky Mountains National Park found 2,377 damaged trees and 3,366 stumps! Leave woods tools at home 6. Respect Wildlife Research shows that small mammal populations supported by human food reach unsustainable levels that promote disease transmission or starvation during the off-season. Another study found that the cessation of long-term artificial feeding left some animals with an inability to locate natural food. The young of such animals may never learn to forage for natural foods – tantamount to a death sentence. 6. Respect Wildlife Keep wildlife wild. Never feed wildlife or allow them to obtain human food or trash. Wildlife attracted to human food often suffer nutritionally, alter their natural behavior and expose themselves to predators and other dangers. Managers at Grand Canyon had to kill 22 fed deer, some with up to 5 lbs of plastic clogging their intestines. A fed deer in Yosemite killed a small child. 6. Respect Wildlife Displacement – animals are forced away from preferred habitats e.g., food/water sources or cover, either during certain times (temporal displacement) or in certain places (spatial displacement). New habitats are unfamiliar, often have lower quality food and cover, or increased competition and predation. 7. Be Considerate of Other Visitors Social Research on Group Size Studies reveal that > 2/3rds of wilderness visitors report that seeing large groups reduces their feeling of solitude and being in wilderness. However, group size is generally among the lowest ranked problems in comparison studies and < 50% report that seeing large groups is a problem. Research indicates that a group’s actual behavior is more important than its physical size. Large groups can camp quietly away from others and adopt low impact camping practices. Ecological Research on Group Size Only one empirical study and several suggestive studies… Large groups burned more firewood, but less wood per person, than smaller groups. Wildlife would likely be less disturbed by a smaller number of larger groups than by a larger number of smaller groups. Large groups can reduce their impact by staying on wellestablished trails and campsites – a dispersal strategy is more difficult for large groups. Ecological Research on Group Size Large groups substantially expand campsites when they camp even one night on a site that’s too small. Any subsequent use of newly expanded areas prevents recovery. Large groups can reduce their impact by: breaking into smaller groups to hike and camp, confining their activities to already impacted areas away from other groups, meeting infrequently as a large group and only on durable surfaces, and practicing quiet and courteous behavior. The End Happy trails and remember to . . . Sunset, Haleakala Volcano, Haleakala National Park, Hawaii Leave No Trace !