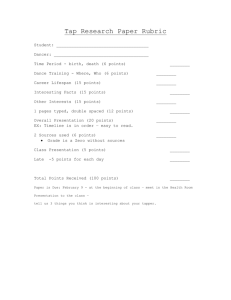

- Edge Hill Research Archive

‘Not With My Body Ya Don't!’ Ageing Performers and the Habitus Turn.

Mark Edward and Dr Helen Newall

Abstract

The catalyst for undertaking this research into ageing performers does not come from academic reasoning and discourse, but from Edward’s journey as a performing subject with a personal experience in dance, choreography, performance and cabaret. This compliments Newall’s work on the documentation of the moving body in performance.

With a focus on second and third age perspectives, we question the negotiation and renegotiation of ageing within western contemporary dance. The subjective nature of this paper arises from twenty years of personal performance histories. The writing thus moves away from the depersonalised third person of academic script and into the more personal narrative of a heuristic methodology of self reflexive research which concerns itself with observations of practice and engagement of self/people.

We challenge longer standing conservative and tacit traditional notions of what constitutes best performance practice and technically embodied techniques. Such forms of dance ultimately result in a reconceptualising and reconciling as the body ages. We explore how engagement with dance needs to be more nurtured and specialised as dancers grow old(er), questioning the relationship between the performer and the performance and by doing so challenging the cultural understandings of performing longevity.

The physical and emotional challenges ageing presents dancers can be journeyed and interrogated through a reflexivity and a writing in this work. This includes, but is not limited to: social and cultural diminishing dancing presence, slowly escalating physical disruptions, relational departures of previous dance forms and embodied dance languages becoming increasingly foreign.

Key Words : dance, ageing, technique, embodiment, mature mover, experience, documentation, cultural representation

1

‘Not With My Body Ya Don't!’ Ageing Performers and the Habitus Turn: A

Performance Script

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

MARK EDWARD: Senior Lecturer in Performance, Department of Performing Arts, Edge

Hill University; dance maker, researcher in ageing and performance; queerist.

Dr. HELEN NEWALL: Reader Performing Arts in The Department of Performing Arts,

Edge Hill University; writer; photographer; animator; image maker.

Friend

With cameos from

Barthes, R. and R. Howard (trans.) (2000) Camera Lucida , London: Vintage Books.

Coupland, J. (2006) ‘Dance, Ageing and the Mirror: Negotiating Watchability’ in Discourse and Communication , 7 (1) p3-244.

Daprati, E., Iosa M., Haggard, P. (2009) ‘A Dance to the Music of Time: Aesthetically-

Relevant Changes in Body Posture in Performing Art’, PLoS ONE 4(3): e5023. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005023.

Douka, S., Sofianidis, G., et al,. ‘Effect of a 10-Week Traditional Dance Program on Static a nd Dynamic BalaVassilia. Control in Elderly Adults,’

Journal of Aging and Physical

Activity 17, 2009. pp 167-180.

Elias, Norbert. (1989):

Studien über die Deutschen. Machtkämpfe und Habitusentwicklung im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert

, edited by Michael Schröter, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

(Published in English as

The Germans. Power struggles and the development of habitus in the 19th and 20th centuries

, Cambridge: Polity Press 1996.)

Fergus Early cited in Gill Clarke, ‘What’s Age Got to Do With It? Celebrating the Mature

Dance Performer’, Time Out Magazine , October 2007, 1939, 17-23.

Featherstone, M., & Hepworth, M. (1991) ‘The midlife style of ‘George and Lynne’: Notes on a popular strip ’. In Featherstone, M., M. Hepworth & B. S. Turner (eds.), The Body:

Social Process and Cultural Theory , London: Sage.

Gullette, M.M. (1999) . ‘The other end of the fashion cycle’ in Woodward, K. (Ed.) Figuring

Age: Women, Bodies, Generations. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp.34-55.

Houston, Sara. 2013. ‘Ageing and Society in the UK’ in Amans, D. Age and Dancing ,

Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mauss, Marcel. (1934). Les Techniques du corps. [1]

Reprinted in Mauss,

Sociologie et anthropologie

anthropologie, (selected writings) 1950.

Journal de Psychologie

32 (3-4).

, 1936, Paris: PUF. Sociologie et

Phoenix, C., and A.C. Sparkes. (

2008). ‘Athletic Bodies and Ageing in Contexyt: The

Narrative Construction of Experienced and Anticipated Selves in Time’ in Journal of

Ageing Studies, vol.22 (3), 211-221.

2

------------------------------- (2009). ‘Being Fred: big stories, small stories and the accomplishment of a positive ageing identity,’ in Qualitative Research, vol. 9 (2), 219-236.

Reed-Danaha, Deborah. (2004).

Sontag, S., (1977)

Locating Bourdieu

. Indiana University Press: USA.

On Photography

, London: Penguin Books

3

SCENE I: Development, Discipline, Decay

There is an empty space and a bright spotlight waiting to be filled. The dance of the Dying Swan is about to begin. A photographer waits to capture it. A swan tiptoes onto the stage.

EDWARD: My dancing decay is a foreign body over-exposed in the youth-driven and media-saturated dance spotlight. Such performance-scapes are where the youthful appear to be embraced, nurtured and welcomed and the mature dance memory is rejected. My personal observations support this. Having once been embraced into dance culture, I have developed, disciplined myself and then decayed through it. As I take my exit from the cultural myths I glance towards the stage mirror, where my ageing dance frame is on full display. Like the dying swan I feel I ought to bow out gracefully whilst I still have my dance attire intact. As I make my unhurried exit towards the door (the psychological palms of the hands gently pushing at my lower spine) what do the unblemished youth see? Are they watching the moment of my departure, or are they watching a metonym for the performer I once was, (or could still be? Can I believe I can still do it? And can I still do it, or am I fooling myself that I can still do it? Are they all laughing at me behind my no-longer supple back because I can no longer do it but don’t know it yet?) My career trajectory appears to have been catapulted from a dance world that demands flawlessness and discards corporeal dissimilarity to a world of reminiscence about what I once could do. But who listens? This is a world where dance technique is about youth and for youth. It might dress itself up as having other themes and narratives, but dance is an athletic phenomenon that ultimately celebrates an aesthetic of difficult, and often elitist, corporeal ability which only the young can attempt and achieve; meanwhile ageing, for anyone and everyone, often foregrounds the decline of ability and visibility. But this is a world we have made, not one that need exist, for, as Justine Coupland remarks:

COUPLAND: The notion that ‘your head thinks it can do it but your body no longer can’ chimes poorly with a radical social constructionist view of epistemology where, essentially, ‘the world’ is little more than a social construction.’

(Coupland, 2006: 244)

4

EDWARD: In the meantime, the dancer, once visible and watched, becomes increasingly invisible as they hit their mid to late thirties. This is more prevalent in ballet especially, a rarefied world within a larger dance culture that demands perfection and rejects corporeal or creative difference. Here, some youthful dancers will have already experienced their first painful break-ups with themselves in the professional rejection of not being good enough (or tall enough or small enough) to take it any further. (This is the tyranny of genetics. Maybe soon, we’ll all be tested at five to see who may as well leave the ballet class now before the pubescent lumps, bumps and growth spurts even begin spurting.) But for the ones who make it through this first filter of who will be seen, the next cruel rejection is injury, which cuts short a career.

But if the dancer survives to the bitter end with Achilles tendons intact, there is the final emotional and physical pain of the ultimate and inevitably acquired fault of being old, which precipitates retirement for most dancers at the age of 35 or 40. Fergus Early states:

EARLY: I see the premature retirement of dancers as a colossal waste. In no other sphere would your career end at 35 (1).

EDWARD: Sporting professionals undergo the same professional redundancies and retirements at a similar age (see Sparkes, 2008, 2009). Whereas extensive work has been undertaken into ageing sportspersons, the brutal impact of ageing in dance remains underexplored. Dancers, who remain within the profession, migrate to more somatic forms, utilizing movements that have less impact on the joints, which have already undergone major physical impacts through earlier disciplines forms and techniques. But what about the dances who don’t want to be forced to migrate?

NEWALL: Old people in dance are not invisible: cultural representations of the old are prevalent, but they are often offered in parodies that situate the viewer outside of the aged state, because, after all, getting old will never happen to us. The old are the hags and bags and comedy turns of narratives that foreground the desirability of youth and being young; they are the pantomime dames at whom we laugh as they are outwitted by the nimble and the quick. And here, if the old are not quick (in the Biblical sense of the word quick) then they must be dead. And if they are dead, then they must

5

be the zombies of lost youth shambling too slowly along pavements for the impatient young shopper on a mission to get to Missoni. And since we tame what we fear through laughter, then the old – and nearer to God than us – of necessity become comic figures to be laughed at, to be lampooned for what they can no longer do, and for what we fear they will soon embrace (death is the ultimate curtain call). Posed photographs of old film stars and former models – in Vogue , Hello and the like - are usually narratives of how they have defied age; how they haven’t let themselves go; how they are still glamorous at 50, 60, 70; how they have kept themselves youthful… while the paparazzi shots taken (or stolen) with long lenses and published in Heat or The Daily Mail sidebar of shame usually show how these same stars ‘have let themselves go’. Outside the photography studio with makeup artists and careful lighting, these stars are human. Botox, fillers and peels can only do so much. In the end,

Photoshop is the ultimate age defying beauty therapy: all these things erase age, or the viewer and/or the photograph. And by their prevalence, they begin to erase the signs of age until being older is no longer acceptable within our visual culture. And I hear you whisper under your breath as you read:

READER: So what?

NEWALL: Well, as Susan Sontag notes:

SONTAG: Photographs alter and enlarge our notions of what is worth looking at and what we have a right to observe (1977: 3).

NEWALL: Photographs are thus very much part of our ontological construction of the wider world. They do what it says on the tin: they write in light to tell us who we are, and the body of imagery available to us – in magazines, adverts, films, television, games, etc. – tells us that there are few old people worth taking pictures of, because, it would seem, the visible signs of ageing are not photogenic. And let’s not forget that we want what we see and we see what we want, so we’re stuck in a hermeneutic and hermetically sealed tin.

But, what of the invisible signs of ageing? As any dancer will tell you, the growing stiffness of muscles – which photography does not capture, and

Photoshop therefore need not erase – is an ongoing but invisible indication

6

that recovery post-performance is taking longer and longer, and that the end is nigh. But there are those who, against the grain, defy the nighness of the d ancer’s end and who are vilified for it:

As the next is spoken, the lights dim to a spotlight.

Music begins. An older dancer emerges: her naked back to the audience, she begins to dance, flexing the beautiful, defined musculature of her torso.

EDWARD: In 1995, and as a much younger dance artist, I was fortunate enough to watch (the then 59 year old) postmodern dancer Trisha Brown perform her work If You Could n’t See Me , a solo in which Brown had her back to the audience throughout the whole of her performance. The only visibility was the musculature and skin on her back, which she rippled and folded. She was framed not only by the rich gilt proscenium arch of the Blackpool

Grand Theatre but also by dance pieces before and after this piece performed by her company of dancers much younger than herself. I was mesmerised by this older dancer and the rippling of her skin and the movement of her breath. Her hair was loose and greying. She was n’t pretending to be anything other than she was. And it was beautiful. But as

Brown intensified her dancing a friend of mine leaned over and whispered in my ear:

FRIEND: The reason she won't show her face is because she's an old bag and really shouldn't be dancing.

EDWARD:

At the time, I wasn’t angry on Brown’s behalf, in fact, I laughed, but I was confused, because this was a signal that I shouldn’t find this beautiful. The next night, Brown did not perform this piece and other friends who went to thi s second night were disappointed that they’d missed this legend of postmodern dance perform the piece.

NEWALL: Were you on the front row?

EDWARD: Silence. Second row.

NEWALL: Do you think she heard you?

7

EDWARD: Silence . Guilty?

NEWALL: Perhaps she heard you and your friend, the comment and the laughter…

EDWARD And the payback is that I have since become that dancer. And now, if I could watch that piece again, I would totally ‘get it’: I wouldn’t objectify her performing body in terms of technique, and how it is worn like a straight jacket by the body. Now, I would see the living archive in a body that has danced beyond technique and which now performs itself. I wish my younger self could have understood that.

NEWALL: But knowledge is wasted on the young.

EDWARD And sometimes on the old if they believe the laughter of the young…

NEWALL: And now someone determined never to get old sits in the second row and laughs at you.

EDWARD: Which is why I work with comedy: I get the first laugh in before the young can laugh me off the stage.

Trisha Brown swirls off the stage in a flamboyant flurry of rippling back muscle.

NEWALL: Such dominant narratives of the old outstaying their cultural welcome appear to be entrenched in Western performance. The loss of roles for older female actors has long been noted. We perpetuate a culture where ageing dance bodies have either a diminishing visibility or waning integrity.

In ballet, for example, those who do manage to remain within the profession are often given the 'character' parts. The traditional shift in ballet of mature dancers to character roles may keep them performing, which is to be applauded, but these roles are often emphatic in their rejection of age as an ugly thing, for these roles arguably caricature ageing since what is performed is often a totter in a parody of age and the lack of mobility it might bring. Thus age is represented as comic but also, as Houston notes, it is threatening:

8

HOUSTON: Some principal dancers, especially in ballet companies, are kept on as character dancers, but this is invariably means either becoming token kings and queens or becoming the ugly sisters, the wicked witch or fairy, or a rather stupid and ugly comic loner. The association of the older person with unattractiveness, with crankiness and above all with witches is played out in dance. These myths and representations of the older person are still endemic in Western culture and are still active in dance (in Amans, 2013:

16).

NEWALL: Dancers fade from view once they hit their mid to late thirties when younger more agile bodies draw the gaze. Is this because as audiences we prefer not to be reminded of our own ageing? Perhaps the almost impossible achievements of young dancers, and for that matter sports and athletics stars, celebrate the pinnacle of human physical ability in a visceral way: while they defy gravity, and move harder, stronger, faster, we can forget our own physical mortality for a brief, moment.

We’re not suggesting that older dancers be cast in roles that they can no longer physically accomplish. The physical and emotional demands of dance are, after all, exhausting. Technique, imposed on the body in a strict system of codification such as ballet, demands perfection. For whilst the young dancer is not immune to injury that might cut short a career, the older dancer is subject to the inevitable decline of what was once possible. To put it bluntly, ageing blunts technique. And in such a visually recorded society, today’s audiences (not to mention the dancers themselves) can see who they aspire to be and what they used to be.

FEATHERSTONE: Day-today awareness of the current state of one’s appearance is sharpened by comparison, with one’s own past photographic images as well as with the idealised images of the human body which proliferate in advertising and the visual media. Images invite comparisons: they are constant reminders of what we are and might with effort yet become

(2001: 179).

NEWALL: Comparisons via photographs inevitably bring self-evaluation. But photographs are always images of dead people:

9

EDWARD: I used to be a clubbing dancer deep in the rave and ecstasy culture. I used to be a contemporary dancer exploring modern and postmodern cultures; but after a while, I didn’t want to carry a dead man or woman on my back, lipsyncing on my skin the practices of choreographers no longer with us.

So, after a while, I had to ask: where is my identity in this technique? Now I am engaging with somatics and a person-led, truth-led practice.

NEWALL: And let us not forget that, in our cultural narratives, dancers are often represented as fragile and ephemeral things, rather than the tough athletes they are, used to the hard physical slog of daily class which gets harder with age. The archetype of the physically and/or mentally injured dancer –

Black Swan , The Red Shoes , and Benjamin Button

– is a persistent and potent tragedy of performance beauty cut short. You can see the scriptwriters’ point of view: the sudden twisted ankle (simultaneously rendering the heroine helpless, whilst reinforcing her frail beauty), or even the car crash and the whispered line of the Sunday matin ée melodrama,

‘She’ll never dance again,’ is more dramatic than the pragmatic truth of a rheumatic knee that aches and creaks with each développé at the barre.

Ageing is a slow time-dependent process that narratives shun. It’s a slow motion car crash that no one wants to watch.

EDWARD: In terms of social and cultural influences, including the media, mainstream

Western dance also shamelessly moves us to a ‘body normative’ which involves the removing of personal expressions and age-crease giveaways.

This ultimately excludes. And this body fascism begins at the first audition.

We’ve already mentioned the crime of being too tall or too small. There also appears to be an expectation of 'dancing your age' for professional dance artists and an insistence upon youthfulness, athleticism, strength and the virtuosic. Dance, like sports, is a discipline training that usually begins in youth, because the body must be moulded. And the life-span of a dancer or athlete is dictated by ability measured against a set of exterior criteria. The question to ask is why does early departure occur and where does this expectation stem from?

NEWALL: We suspect it is imposed by the subtext of the attainment of ability, and by audience expectation. Dance does not measure who can jump the highest, as is explicitly the case in sport, rather dance purports to move us

10

emotionally, but when someone comes along with brilliant and sparkling technique, someone who can jump higher than anyone has seen before, then this is the star the audiences clamour to see. You see, although ballet is a fixed codification of performance language, a drift may occur over time, exacerbated by evermore technically accomplished bodies. Research in this area has been made by Elena Daprati, Marco Iosa and Patrick

Haggard, in ‘A Dance to the Music of Time: Aesthetically-Relevant

Changes in Body Posture in Performing Art’ (2009). Daprati et al studied the height of leg extensions over the course of decades of dancers performing the same role in Sleeping Beauty .

DUPRATI Ballet positions are codified, and limited by biomechanics' rules.

Theoretically, they should present in identical form across time, except for slight random variations due to variability between individual dancers.

(2009: online)

NEWALL But they found that the height of leg extensions has increased significantly without affecting trunk position.

DUPRATI: Perhaps the dancers earlier in our period would have produced leg elevations equal to those seen more recently, had they been physically able to do so. That view suggests that dancers have throughout strived for a “perfect” body position corresponding to a universal aesthetic goal.

Recent dancers have come closer to achieving this goal due to their greater fitness and skill.

NEWALL: But Duprati et al note that fitness does not explain cultural taste.

DUPRATI: An alternative view suggests that aesthetic goals are not fixed, but vary, despite the stabilizing effects of codification and tradition. On this view, historical changes in body position at fixed moments of choreography would reflect secular changes in what body positions are given high aesthetic value by prevailing artistic culture. This evaluation presumably reflects the opinions of directors, audiences and dancers themselves.

NEWALL: So, as taste dictates higher leg extensions, which necessitates fitter dancers, it excludes even more sharply those who can no longer maintain

11

such high levels of achievement. But such taste might be altered by shifts in visibility, which must come from within the industry itself. And whilst ballet is a strict codified system, which, as Duprati has shown, is not as fixed as we might think. It will nevertheless not accommodate ability in decline; rather it seems to be demanding ever more ability. Ballet is thus not the forum in which to challenge the monopoly of the young. Technique rich forms are athletic and aesthetic. So how might older dancers be accommodated?

EDWARD: Increased visibility of ageing flesh in dance concerns the dismantling and the disrupting of the stereotype and visually challenges the legitimatisation of what body should or should not dance. It involves a cultural critique of ageing and for the older dancer to 'reconnect with one's distinctive life story and unique subjectivity' (Gullette, 1999: 55). In Kontakthoff , Pina Bausch choreographed the same piece on both younger bodies and aged bodies.

Originally performed in 1978, the work was performed in 2010 by an older cast (men and women aged over 65), and then, on the following evening, by a younger cast (aged under 19). Bausch thus exposed and explored how mature performers do not necessarily have to be the older backstage mentor of younger skin, and highlighted that the mature performing body should and can be culturally seen with no ill effects. Performance can contain age, demonstrating how mature movers have the capacity and visibility to move them beyond a performance culture that discriminates.

Bausch ’s example could be a springboard for many other choreographic laboratories.

SCENE: Frantically Paddling Ducks and Dying Swans

The Dying Swans retakes the stage and fettles her feathers and is spot-lit as she pirouettes and dies about the stage.

NEWALL: We have spoken of this before. In a poster presentation for the international congress, Tanz in Der Zweitenlebenshalfte (D üsseldorf,

2013), we stated that: ‘The ballerina as the dying swan symbolizes the tragic death of youth, and with it, beauty. Poignancy lies in the unconscious allusion to the inevitable decline of a dancer’s ability and stamina. Swans and ballerinas never speak; voices would break the spell

12

of the ethereal aura with which they glide effortlessly over the surface of their corporeality. Their delicate aesthetic denies the body its athletic training and strength built up over the years of discipline at the barre.

Beneath the water, the swan’s feet are paddling. Beneath the glamour of the performance, the performer’s feet are aching, arthritic and deformed.

Beauty is ephemeral; grace is a set-up. Feet, en pointe ache; smell, stumble.

EDWARD: The third aged dancer is all too familiar with physical pain, but it is underscored with a sense of loss, a knowing that what has become is now departing. Emotional pain is a frequent companion as the body, through dance, is on the margins of performing body-normativity. It is thanks to the development of th e mind and the security one finds in one’s own skin that body-normativity is not encouraged. Educating the dance artist requires dancers to be comfortable in their own skin, not to embody and fight a living contradiction going against their natural ageing inscription. Such contradictions are regurgitated from expanding commercial culture and archaic social and institutional dance ideologies where institutionalised ageist-phobias disempower, demoralise and contribute to selfworthlessness. Equally prolific is depression and a creation of a negative self-image in dance and performance arenas. Dance artists often have to grapple with hostile working environments as it is, without the added ageist policing of their every evolution.

The notion that aged bodies cannot dance is a myth: an ageist myth often accompanied by its malicious accomplice: mirrors. We should enjoy the body we have/are and acknowledge that dance is a broad arena, and that each individual is a work in progress in a unique process of a state of permanent evolving, growing and becoming. Performing artists should enjoy mapping their bodies in space through self-identity and ownership of the dance language (whatever that maybe) regardless of its size. We need to embrace the idea of people being a habitant of their own skin being able to execute their dance ability with confidence and (re)assurance.

Is it with age, and performing maturity I can say this? Do I have a more refined knowledge of dance language in my bones as opposed to a refined figure? I may not have a great body but I do have a great attitude towards

13

dancing. Organically, with this wisdom, I have moved away from having to conform and perform to a set of soul-crippling codified established practices and dancing idea(l)s, and have come to recognise that I am free to dance as I like when I like. As an older artist, I can readily engage with and draw upon a range of embodied knowledge with substance, truthfulness and lived experiences, and perhaps body acceptance is part of this. Bein g comfortable in one’s own skin cannot be taught: it has to be embodied and accepted over a period of time. We are in constant dialogue with our bodies, resulting in the rich intense relationship we have with ourselves. The dancing body should not be age questioned, architecturally refined, but should be celebrated in all its evolving and differing forms.

SCENE: The Corps de Ballet execute a Magnificent Habitus Turn

EDWARD is joined on stage by BOURDIEU, ELIAS,

REED-DANAHA and FREUD, all whispering in his ears, all pirouetting.

EDWARD: For Bourdieu, the ‘habitus’ is not a socially constructed concept, but something internalised and embodied. It is not consciously understood within groups of people, and its construction is acquired through childhood.

This idea was reconceptualised by the sociologist, Norbert Elias is famous for his work

‘

The Germans: Power Struggles and the Development of

Habitus in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries’. In this text, Norbert

Elias refers to habitus as:

ELIAS: A second nature.

EDWARD: Influenced by Freud (

who bows

), Elias conceptualises habitus as a form of personality structure, acquired through embodied social learning. Elias’s theory on habitus envisages a group of people with shared ‘habitus’, thus combining,

ELIAS: the self-image and social make-up (1989: ix).

14

EDWARD: Thus, age becomes a characteristic through which an individual performing body can differ from other members of its field, whilst yet remaining part of the field: it should still therefore be embraced as part of the social and performing make up. Elias has a term for this:

ELIAS: The ‘we-I’ balance,

EDWARD: which reflects this dichotomy of the individual and the dualism of the performer. Reed-Danaha comments thus:

REED-DANAHA: “we-feelings” are part of the social habitus and can be provoked by [...] some social groups, in order to survive as a group (2004: 105).

EDWARD: Marcel Mauss, influenced by Bourdieu’s use of the term habitus, describes how habitus can vary across societies, educations, and, I would argue, performance arenas. His essay ‘Body Techniques’ explores how movements can be socially constructed:

BORDIEU: In them we should see the techniques and work of the collective and individual practical reason (1950: 101).

EDWARD: Putting these iconic philosophers and sociologists in dialogue with one another is illuminating from a dance and ageing perspective: it offers an opportunity for dance cultures to embrace ageing performers. Age, as a social construct, rather than being implicitly linked with vulnerability, decay and loss, can be used to denote wisdom, embodied techniques, dancing histographies and biolographies.

BOURDIEU, ELIAS, REED-DANAHA and FREUD exit chased by the bug-bears of growing old.

SCENE: Dancing Into The Future: hipsterectomy and beyond.

The 35 year old Swan settles, breathing heavily, gasping for a cup of tea, maybe even a fag, before setting off again, fluttering and rippling her back and her double jointed arms, doing the dying thing.

15

NEWALL: We shoot people with guns and cameras. And photographs and mirrors tell us we are old. Roland Barthes would have it that photographs show us those who are not yet dead long after they have died (2000: 96).

BARTHES: With the Photograph, we enter into flat death (92).

NEWALL: This is the cultural pain for the dancer. This is a mini-death for in capturing one moment that is dead and gone as soon as the shutter clicks, the photograph underscores faded technique by whispering:

‘This is what you used to be able to do’. But whilst photographs, and our aches and pains remind us time marches on and that we are growing old, it is often said:

A CHORUS in clichéd clothing shuffles onto the stage and holds up a mirror.

CHORUS: My body feels old but my mind feels the same as it did twenty years ago…

NEWALL: ( Screams ) That’s not me in the mirror; that’s my mother!

The CHORUS sighs in agreement and takes the mirror off stage, breaking it as they go.

NEWALL: ( Regains composure ) Coupland cites Woodward:

WOODWARD: Our bodies are old, we are not. Old age is thus understood as a state in which the body is in opposition to the self. We are alienated from our bodies' (in Coupland, 2013: 5).

NEWALL: Perhaps if we could reacquaint ourselves with ourselves, we could defeat the alienation and defy the Cartesian mind/body split that seems to cause us so much distress. Personally, however, I don’t feel the same as I did when I was twenty. I used to be afraid. I used to be gauche. I used to be naïve. With age, I think I am morphing (physically and mentally?) into Rhett

Butler.

16

BUTLER: Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn.

NEWALL: This is a freedom! (Apart from the postmenopausal moustache. I’m not overly fond of the freedom of that!). It is also the tragedy of increasing wisdom coming at the expense of the decline in physical ability. If I knew then what I know now...

so the saying goes. And it’s true isn’t it? The beautiful young who do not have the experience to grasp deeply the full import of a given role because they have not yet lived. Youth is wasted on the young. But they have something to teach us. They move; they move on; and they think they will go on forever. But what about us? We must not lose sight of the fact that we will not go on forever. But we could start acknowledging that culture is not a young thing. It’s as old as the Greeks.

O lder even. It’s as old as the hills, in fact. And it’s likely that dance and song are as old as firesides when the elders, and the knowledge and the wisdom they had acquired, were revered.

EDWARD: It is becoming increasingly apparent that engaging with dance is beneficial to athletes and older people alike. Many recent studies affirm this

(Sofianides, 2009; Gayvoronskaya, 2010; to name but a few). And as we’ve seen, age is not unbeautiful. Not all dance need be athletically challenging nor balletically, technically pristine.

NEWALL: I once saw in Southern Spain, far off the tourist track, a flamenco dancer all in black and a guitarist dancing and playing on a dusk street corner. She must have been all of seventy. Maybe older. And she was matronly, not

Blood Wedding virginal slim. Her face was lined with decades of sun. He was older, his fingers as brown as olive twigs, but plucking and slapping a rhythm to match the furious stamping of her staccato heels in the dust. It was mesmerising. Mark wasn’t there. Nobody laughed. He would have loved it.

EDWARD: The issue, then, of older dancers leaving the profession becomes even more nonsensical. There is something about the accumulation of experience that emerges in performing that has very little to do with technique. As time goes on, dance becomes less about technique and more about somatics, about the uniqueness of the individual body, rather

17

than having to conform to a set of practices and ideas. This is where a new visibility could lead us.

NEWALL: And so, in a practical project, Dragged up Dames and Dying Swans , we engage in dancing for the camera. It does not involve long dance scenes, but invokes a performance that the viewer must imagine via the documentation of a performance that never happened. There is comedy in the images and tragedy. And there is the fact that both moving repeatedly for the camera and crouching to take pictures is physically demanding in a new sweaty way. Because, in the end, the most perfect performance is the one you imagine when you see the images of a long gone production. This defeats age, defeats the wobble on pointe, and adds a few image drops of old geezers to the oceans of images of young dancers leaping effortlessly into the infinity of Barthes’s flat death .

EDWARD: We acknowledge that there will be no conclusive and affirmative answers.

Rather this work documents this journey of change and fluctuating attitudes towards the ageing and size expanding body in dance culture. In some respects the process is a route to self-enlightenment, moving away from previous performance practice using codified technical material that may no longer serve a function under the skin. What we aim to explore are the ways that the documentation of the performing self can afford a healthier option in resolving and enriching experiences getting older.

We have no intentions of wanting to become the heroes of ageing narratives nor have intentions of erotising a personalised ageing flesh. We are simply embarking on a reflective journey of change in order to generate a space for the dancing self that is less volatile for the maturing performer, moving away from previous unforgiving performance and descending social arenas.

We can return to sender our golden tickets to a lifelong membership into the choreographic graveyard. Instead we relish in the perceived grotesque aspects of dance with a sense of mischievous play, making visible the

'misshapen' in classical dance and a re-figuring and re-framing of the body which appears to have withdrawn from conventional expectation and

18

presentation. A sort of rebellion underscored (or over scored) with a dynamic visibility.

The swan coughs and dies.

Black out.

NEWALL and EDWARD stumble off the stage, bumping into the furniture.

19