Slides

advertisement

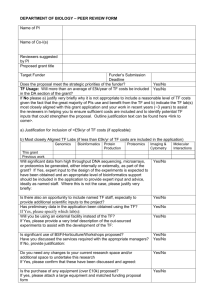

Heidi Julien, Ph.D. The University at Buffalo To articulate a research plan To convince others that the plan is sound Funders Colleagues Supervisors Convincing proposals are Conceptually strong Based on demonstrated value Based on feasible and logical plans Submitted by demonstrably competent proposers Tailored to the specific requirements of the evaluator(s) 2 • Doing what’s asked • Doing it well • • • • thoroughly with attention to conceptual and logical consistency with attention to detail with an eye to demonstrating you are competent • Doing it on time • Aligning your research and organizational purpose to the funder’s purpose 3 • Review Criteria: • Evidence that the literature review includes relevant research and/or projects • Evidence that the needs assessment clearly articulates the project audience and its needs • Evidence that project activities and goals directly address the needs of the identified audience • Evidence that the project will increase the number of qualified professionals for employment as librarians or archivists • Evidence that it will build greater skills and abilities in the library and archives workforce • Evidence that it will contribute to results or products that benefit multiple institutions and diverse constituencies . . . 4 • Justification – answering the “so what” question • Make your case convincingly • Refer to short-term and long-term value • Contextualize your study • What are the important theoretical and practical questions? • What does the literature have to say about your questions? • Can you demonstrate a need for your research? • Articulate research questions • These should flow logically from the research problem and context • Specific the research design • • • • How will the research questions be addressed? What is the theoretical perspective being taken? What data collection methods are proposed? How will data be used and secured during and after the project? 5 • What do you know about the funder/agency? • What do they like to fund? • What sort of projects are they encouraging? • Analyze your own proposal ideas • What’s been done before-by you and by others? • Why is this important? What is the value? Who may benefit? How might they benefit? • Have your methods and operational details clearly in mind 6 Methodology and methods Research questions Research problem and literature review 7 • Articulate answers to: • • • • • Who What Where When How • Describe ethical issues, and how these will be addressed—is there a policy to be followed? • Is formal approval needed? • From what body or institution? • Is an application required? 8 • • • • • • • • • How this project differs from previous work Known limitations of the study Parameters established (what’s in, what’s not) Assumptions being made Methods being used to ensure trustworthiness, validity, reliability Projected venues for dissemination of results Timeline Budget (funding, equipment, personnel, supplies) Detail who’s doing what • Address each team member’s competencies • Discussion of partners or advisory / oversight groups? • References (use recommended style, be honest about the current status of your publications) 9 • ALWAYS follow agency/institutional guidelines • Be realistic, justify expenditures • Do not ask for more than you need—inflated budgets are obvious to experienced reviewers • Ensure correspondence between your narrative and budget requests • Project if you need to (e.g., for salary increases, inflation— make percentage changes uniform) 10 • • • • • • Writing style Structure and layout Argument Attention to detail Attention to stated requirements Attention to unstated requirements 11 • Write for comprehension • • • • • Be clear and concise Be consistent and logical Use future tense (“I will do”) Be confident, but not grandiose Use active verbs • Know whether you can use first person or need to use third person • Write for an educated but not expert reader • Do not make assumptions about shared understandings or background knowledge • Seek feedback on drafts to ensure completeness and accuracy—NO grammar, syntax, or spelling errors! • If you are writing in a second language, take extra care 12 • Present your argument logically • Follow directions about sections required • Include all sections required • Carefully consider whether adding “extra” sections is appropriate – the answer is usually NO • Use sub-headings to guide reader • Follow layout instructions (do not get creative) • Do not use font < 12 pt. • Use white space, leave margins • DO NOT EXCEED PAGE OR SECTION LENGTH LIMITS 13 Rhetorical moves 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Establish the importance of the issue or question Establish a gap in the work so far Define novel contributions of the proposed work Demonstrate feasibility of plan Demonstrate knowledge of the issue or question Demonstrate record of success (individual and/or team) 7. Show one’s unique positioning to complete the work 8. Demonstrate fit with the grantor and opportunity 14 • • • • • Prevalence of the problem Burden of the problem Cost of the problem A hard problem that has resisted easy solution Social benefit if the problem were solved 15 A. Assessment of Need Access to health information is, unfortunately, differential in communities across the United States. And those groups who have the most difficulty obtaining needed information are often those who experience worse health outcomes (“health disparities”). Increasingly, research has revealed that community-level health disparities may be linked to the environmental features of the neighborhoods in which many socio-economically disadvantaged people live—communities like Inkster, Flint and Northwest Detroit in Michigan… 16 • …Yet little is known about the role that information exchange dynamics and infrastructures may play in community-level access to health information. 17 • To aid in greater understanding of these issues, this project will be the first to investigate the health information access/exchange/use characteristics of three urban communities from the point of view of their “community health information infrastructures.” This novel conceptual approach will build on an assumption that this infrastructure is amenable to description, intervention, and change. 18 • Health information is a critical resource for people facing health issues. For example, health information can help people to: make decisions (Fox, 2009; Livneh & Martz, 2007); solve problems (Endler & Parker, 1994; Farber, Mirsalimi, Williams, & McDaniel, 2003; Folkman & Greer, 2000; Stanton, Revenson, & Tennen, 2007); pursue or coordinate new lines of action (Schaefer, Coyne, & Lazarus, 1981; Siegel & Krauss, 1991; Skinner, Edge, Altman, & Sherwood, 2003); gain mastery over health challenges (Folkman & Greer, 2000; Skinner, et al., 2003); use resources more effectively (Moos & Tsu, 1977); change their behavior (Fox, 2009); share social support with one another (Berkman & Glass, 2000); and provide informal health care to others (Fox, 2009). 19 • This project will adopt a mixed methods approach similar to that used in the PI’s previous research (Veinot, 2008). • Pilot work, especially if published. 20 • F.2 Personnel • Dr. Tiffany Veinot, Assistant Professor, University of Michigan School of Information (SI). To accomplish the goals of this study, Dr. Veinot draws from her experience as an Investigator for five extramurally funded grants and from her strong publication record. The proposed project will particularly build on and extend approaches and insights from Dr. Veinot’s award-winning research regarding health information behavior in communties and families. Dr. Veinot has ten years of professional and managerial experience in non-profit information organizations, which will help ensure this project’s effective management, as well as its effective relations with community partners. 21 • …The proposed planning project aims to capitalize on the commitment of local libraries and other community organizations…. 22 • C. Support for the priorities of the National Leadership Grant Program • C1. Projects address key needs and challenges that face libraries. The IMLS argues that “there has never been a greater need for libraries...to work with other organizations in effectively serving our communities…” and that libraries should “…[b]ecome increasingly embedded in the community in order to create lasting partnerships that address 21st century audience needs” (Institute of Museum and Library Services, 2009, p. 37). Professional literature also suggests that libraries should adopt a more systematic and proactive approach to partnerships (e.g., Crowther & Trott, 2004). 23 • Know the politics of the adjudicators • Reference to (or avoiding) particular methods, approaches, theories, viewpoints • Reference to particular authors, literature • Avoiding certain jargon or terms (e.g., “training” in educational contexts) • If you can suggest adjudicators’ names, choose wisely • They should be familiar with your work and field • They should be authoritative within your field 24 • Express appropriate appreciation for the complexity of proposed work • Anticipate possible problems, and state how to address • If there are many interdependent activities, provide a contingency plan • Explain how all expertise needed for project is represented on team • Ensure fit between prominence of an activity and financial support for it • Thoroughly respond to earlier reviews 25 • • • • • • • • • • Accomplished Dedicated Knowledgeable Conscientious Fair Overcommitted and overworked Exhausted Under-compensated Skeptical and critical Looking for ways to make reviewing easier 26 • Plan to draft several iterations, so start early • Seek advice from experienced adjudicators, and successful colleagues • Give reviewers plenty of time to read • Consider suggestions carefully – you don’t need to accept all advice, but think about it • If you have a question about the funding program, consult with the program officer, and your institutional support personnel • If your project is not funded, use the feedback and advice provided to re-apply 27 • Know why the collaboration makes sense – articulate the reasons, the advantages • Clarify expectations • goals for the project • authorship, travel, publication venues, timelines • Communicate clearly and often, and don’t make assumptions • Value the expertise and skill set that each partner brings • there may be differences in training, experience 28 • Cautions • Terminology – do not make assumptions about shared understanding • Disciplinary differences may include norms regarding: • Assigning authorship • Productivity • Roles, responsibilities • Working styles • Appropriate publication venues 29 • require competence on the part of all the collaborators (that competence can rest on different strengths, of course) • mutual understandings (or agreements) about working style (e.g., deadlines, form and quality of work products) • a shared and mutually understood goal • mutual respect, tolerance and trust • the creation and use of shared spaces (real or virtual) • multiple forms of representation (to enhance shared meaning) • opportunities to “play” with ideas without commitment or fear of ridicule 30 • continuous, flexible communication (not necessarily continual), • often require both formal and informal for interaction environments • clear lines of responsibility (but not rigid boundaries) • recognition that • decisions do not have to be consensual • physical presence (though useful) is not necessary • selective use of outsiders for complementary insights and information can be beneficial • collaborations end (they are purposeful and when that purpose is achieved, the collaboration ends) 31 • At many agencies, fewer than 10% of proposals get funded • Reviewers are experienced and highly critical, so are looking for opportunities to reject proposals • What does NOT get funded: • • • • High risk projects Ideas that have been extensively explored previously Bad ideas Poorly written proposals 32 • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Lack of sufficient commitment/time Problem isn’t shown to be important Insufficient knowledge of literature Lack of essential experience of applicant Diffuse, superficial, unfocused approach Applicant did not follow instructions Unrealistic amount of work proposed Uncertain outcomes and future directions Unrealistic budget Not relevant to mission of funding agency Reader-unfriendly application Misinterpreted deadline for submission Applicant did not address review criteria Work already done by others 33 • Proposal and grant-writing success comes from: • • • • Doing what’s asked Doing it well Doing it on time Aligning your research and organizational purpose to the funder’s purpose 34 Questions? 35