Crash Course in Fiction

advertisement

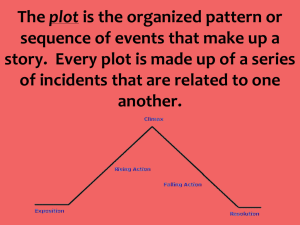

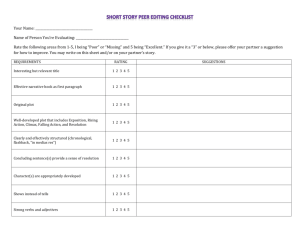

Interested in Writing Fiction? A Crash Course in Creating Characters, Plot and Setting Note: this presentations covers a lot of info! If you feel overwhelmed, concentrate initially on slides #1-10, 20, and 25-32. First, a quick review of a couple important points… What is the difference between an essay and a story? Beginning writers sometimes confuse these. Essays have a thesis, are primarily factual (nonfictional), expository (explanatory), and reflective. The “narrator” (the voice speaking the essay) is the actual author, and any people referenced are real, living individuals. Stories don’t have a thesis, are primarily dramatic and “made up,” and are narrated by an invented character or an omniscient speaker. People who are referenced in a story are invented characters. Take care that you don’t confuse a first-person narrator of a story with the author of the story! They are not (necessarily) the same person! We’ll be discussing this in class at some point. So... Go give away your dollar bill. Yeah. Really. Go outside, select someone, walk up and give them the money. Or wait for someone to walk past you. Or whatever. You can’t explain why. Just say “Here” or “This is for you” or something similar. Now... Don’t talk. Don’t ask any questions. Get out some scratch paper or open up a blank Word .doc and write. Describe what happened in a paragraph. You can reflect a bit if you like, but be sure to describe the what, where, who. In concrete, descriptive detail. And finally... what is the story in what just happened? How do you locate the “story” in any set of events? Sketch a story called, “The Dollar Bill”: • • • • • When/where does it begin? Who is the main character? What is the primary problem or narrative question? What is the point of view? How do events unfold? Where does each scene stop and start? • When/where does it end? • What is the story’s primary effect, theme, and mood? When you are waiting or searching for a story...what are you waiting or searching for, exactly? Good bets are: • Interesting images that catch your eye or linger in your mind or haunt you. • People who strike you as interesting and you’re not sure why. • First lines that simply come to mind. “The most puzzling element of her day was the black hat.” • A scene from your everyday life in which you notice an interesting contrast or question. Also, good bets for stories very often involve character rather than plot. And a character’s desires are almost always interesting. For instance: • Someone desperately wants something they can’t have. • Someone gets what they want, and it turns out to be [tragic, funny, shocking]. • Someone wants x, but the reader can clearly see that what they actually need is y. The Elements of Fiction Plot Characterization Setting And Some Other Stuff Note that experimenting with plot is one of your options for your Fiction Project! Ok. Plot What is it? How do you make one? How do you make a GOOD one? Fun facts: the word “plot” in fiction actually derived from the word “plot” used in farming. Plotting a Story What's a plot? o The sequence (or pattern) of events in a story. “First this happens, then that happens, then this…” What sets a plot in motion? o Hint: when this narrative question is linked to CHARACTER, you have a stronger, richer story! A QUESTION is posed, explicitly or implicitly. We call this the “narrative question.” So why do we we continue reading? What keeps us turning pages? Say this is the first line of a story: “Stan Studly was climbing a mountain.” Ok, so what is probably going to be this story’s narrative question? Right! “Will he make it to the top?” This question is implied, and, sure enough, the reason we continue reading is TO GET AN ANSWER! Now, what are the possible ANSWERS to such a question? The possible answers are: YES! or...let me guess... NO! Nothing wrong with a story like that; it can be quite good, even exciting. But that’s a pretty simple plot basis. You can do quite a lot more. Suspense and interest can get REALLY intense when ADDITIONAL questions are introduced, and/or when the question(s) posed has multiple possible answers. Stan and Frank are climbing a mountain. Stan is having an affair with Frank’s wife. More questions So, NOW what’s the narrative question(s)? and/or more possible answers • Will they make it to the top? • Will one make it and the other fail? • Will Frank find out that Stan is having the affair? more • What will Frank do when he finds suspense! out? = & possibly a richer story. Of course, there are other ways of thinking about how a plot gets “jump-started”: A balanced situation becomes… Or an obstacle is presented. The more obstacles, the more potential suspense. Usually :) Whatever the case... what gets a story going, what keeps us interested, is that... SOMETHING IS WRONG! If nothing’s wrong, if everyone’s happy, there’s no story. I mean, screw happy people! Who cares, right? Ha ha. Joking. But really. It’s human problems that engage us. Just ask any soap opera or computer game addict. We want to read about the problems people face and how they do (or don’t) manage to deal with those problems. Another way to think of PACE, in fact, is the RATE OF REVELATION. What else is important to plot? PACE What speeds thepace? slows the Exposition. pace? Interior monologue. • ACTION! Description. • Revelation of Dialogue. Sub-plots or parallel plot ANSWERS to(more the on this is just a sec) narrative False clues, misdirection, or otherwise questions withholding answers to the narrative question. We may and probably will discuss each of these at some point in class! Helpful Plot Devices Framing (we’ll talk about this more in a sec) Flashbacks Foreshadowing Parallel or intersecting plots or sub-plots (more in a sec) False clues “Hooks” (these are not so much “devices” but integral elements; sometimes they’re referred to as complicating actions, triggers, or twists) Delay (withholding answers to the narrative questions) Plot Structure So, what’s the shape of your plot? How do its parts fit together? A traditional, linear plot... is one we are all most accustomed to. A series of actions occur, a problem someone is facing gets worse, and, just when we think the problem will destroy the person, the day is somehow saved. That’s a crazy oversimplification—so let’s look deeper... “Triggering action”= SOMETHING GOES WRONG. Equilibrium becomes DISEQUILIBRIUM. “Hook” = complicating action. Increasing tension X X TRADITIONAL PLOT STRUCTURE: standard rising and falling action X X X X X Scene-setting: where, who, when? (sometimes called “exposition”). Equilibrium. Balance. Here are additional possibilities in a traditional plot: False clue Increasing tension X Partial answer X Introduction of minor parallel plot TRADITIONAL PLOT STRUCTURE X X X Flashback What SLOWS Pace? X X X X X X Scene-setting (exposition). What SPEEDS pace? ACTION! ANSWERS! Even partial answers! Dialogue. Description. Minor parallel plots. False clues. Flashbacks. Internal monologue. There’s nothing wrong with a traditional plot structure! And did you know: each carries with it its own ideological assumptions about the nature of time, desire, purpose, even human existence itself? Feel free to research more info on anything here! Alternate Plot Structures (and devices) Different plots can express Montage or collage. (Tim O’Brien story which we will read for class.) alternative ways of Multiple and intersecting plots. (I’ll tell you about a novel, Continental Drift.) experiencing Chronologically TIME andbackwards plot. (Yes—backwards. See Lorrie Moore’s “How to Talk to Your Mother.”) REALITY! See Garcia StaticGabriel plots. (See experimental stories by Robbe Grille.) Marquez’s One A story made entirely of flashbacks, or footnotes, or exposition. (I’ll tell Hundred Years you about Nicholson Baker’s, The Mezzanine.) of Solitude. Framed narrative. A story within a story. (Have you seen Titanic?) For your fiction project... I’d suggest a simple, traditional, linear plot, if you have not written much fiction before. Plot Thingys to Avoid (none of this allowed!) The “it was all a dream” ending. (Besides the fact that it already happened to Dorothy, it’s just a cheap solution to the difficulties raised in the story.) Suicide endings. (Sorry—your characters will have to find some other way out of their problems. Avoid this kind of ending, at least for now.) O’Henry twist endings. (Clever, but get old fast. The twist becomes the whole point of the story, gets kind of gimmicky, and ultimately has limited interest.) Tidy, comprehensive endings in which everything comes out well, all loose ends are neatly tied up, and the universe is pretty much explained to one and all. Let your stories end inconclusively now and then. Let them end with questions rather than answers. And Something Else to Think About Does a story have to be plot-centered? NO! A piece can be character-driven, image-driven, idea-driven, even setting-driven. (Look at selected scenes from Robert Altman’s, The Player—maybe I’ll show them in class.) So, a little sum-up: Plot—Don’t Plod! o Be aware of your narrative question. Introduce additional narrative questions. Create multiple obstacles, physical or emotional. o Control the rate of revelation. Slow pace = interior monologue, description, dialogue, exposition. Fast pace = action, jump cuts, answers to narrative question. o Provide false clues, misdirection, to create tension. o Develop sub- or parallel-plots which delay revelation in the main plot, add interest and complexity. o Consider creating your backstory gradually. Don't give main character’s full story immediately. Let it evolve. o Provide powerful IMAGERY which heightens tensions. Students almost NEVER use imagery with feeling. Note: many students are not aware of where their scenes stop and start, and their transitional passages are consequently “muddy”: overelaborated, bogging the whole story down. What else is important to plot? Scene Development o A unit of time and place in which (usually) important action takes place. o Can be like mini-stories within the larger story. Scene transitions o o o Provide a simple extra space on the page. This is common these days. Transitional phrases. “Jump cuts.” Leaping from one scene to another abruptly. Done well, reader intuits the transition. Student stories often have needless exposition and crud between scenes. How long should a scene be? Depends on length of story. Depends on pacing: do you want to speed things up or slow things down? Short scenes obviously go faster than longer ones. Student scenes are often neglected. Too long, too short, non-existent… Characters How do you make them? How do you make them INTERESTING? Types Flat (or Simple, Secondary, Static) Round (or Complex, Primary, Dynamic) Need to Be Try starting with a CHARACTER idea, not a plot idea! Believable, Real Consistent Distinctive Worst beginner faults: characters who are all alike (can’t tell one from the other), or are generic. Starting with a Character Cook up a distinct, rounded, believable character. What is that person’s greatest desire? Primary fault? Greatest fears? Worst neuroses? What makes this person sad, edgy, confused, repulsed? What do they NOT KNOW about themselves? NOW: put that character in a setting and situation which will MAXIMIZE his/her fears, faults, neuroses; a situation which may force them to confront their what they do not know about themselves or what they don’t want to know. Something very handy is... applied to CHACTERIZATION Don’t explain away your characters. Don’t continually TELL us what they feel. SHOW us what they feel. And, even then, let only the tip of the iceberg show—the RIGHT details will evoke the great complex mass of feeling under the surface. Trying to explain a person’s feelings usually oversimplifies those feelings, even cheapens them and drains them of nuance. Provide fewer, but better, details. (Less is more.) E.g., instead of saying that “Sally was taken aback and completely furious”...say that “Sally frowned very gradually, a really long frown, her eyes narrowing like debit card slots on an ATM.” This shows the character’s feeling dramatically and more richly. Instead of explaining everything... o Have your character DO something which reveals interesting nuances of their personality. o Have your character REACT to what someone else does or says. o Show other characters reacting to, or speaking about, your protagonist. o Or, sometimes, just let the most recent action speak for itself. Don’t feel you have to know everything there is to know about your protagonist! In fact, if your protagonist is any good, you WON’T know everything there is to know about the person. Many good writers report that their main characters take on a life of their own, and, just like people in real life, are too complex to be completely pinned down. Silences aren’t silent. Silences aren’t nothing. Being good with words means knowing when to shut up. SETTING and IMAGERY What do SPECIFIC ITEMS in the setting say about the main character? – – – What is in your invented character’s bedroom? What is in YOUR bedroom? What is in the jungle in “How to Tell a True War Story”? What is in the home of the protagonist of “Cathedral”? What mood is created by the setting and by the story’s imagery? How do the setting and the imagery contribute to theme? In what ways might a story actually be ABOUT setting? (setting that is almost a character) Settings can tell us general info about a character’s socioeconomic class or age, but they can also reveal nuances of character and contribute to our understanding of a rich character Beginning writers... always neglect setting :/ And now… Fiction Review Some #1 Things to Look Out For Before handing in any work, ask yourself at least a few of these questions: 1. Does the story rely entirely on plot? Are other story elements—character, setting, perspective, language, image—ignored? 2. Does the plot in turn rely entirely on an "O'Henry twist" or trick ending? This is fun maybe once or twice, but it gets old really fast. You should only be doing this sparingly. The outcome is a foregone conclusion for the writer and so no discoveries have been made. One of the central pleasures in writing—for the writer—has been missed. 3. A related problem is the plot based heavily on a clever, "ooh-aah" or "oh wow" premise. Such a premise or basic concept is fine if the story is otherwise fully developed, but too often the premise becomes the only point, a gimmick of interest for about 3 seconds. Try founding your story on some interesting and unresolved, possibly unresolvable problem of character rather than plot. The premise may seem less snappy or clever at first, but ultimately the story will be richer and take the reader (and you, the writer) into more interesting territory. 4. Is the plot "front-heavy"? That is, does it have page after page of initial scene-setting and exposition, followed by screaming slide to a conclusion? 5. Is there a suicide ending? Come on. 6. Are there plenty of specific, concrete, sensory DETAILS so that the reader can really see and feel the setting and characters? Or is most of the language general and abstract? 7. Are the characters in the story distinctive? Can you tell one apart from the other, or are they all basically the same person? 8. Are the characters developed? Do you really know the central people in the story—their desires, physical quirks, beliefs, contradictions? Does the main character leave an impression? Do you know everything there is to know about the main character? (you shouldn't!). 9. Are scenes* in the story distinctive and delineated? If they all kind of run together, chances are there's a lot of inconsequential action which is diluting the best stuff so we can't see it or experience it vividly. Go through and mark where scenes in the story begin and end, and consider cleaner transitions from one scene to another. 10. Look at the scenes you've marked. Is each one sufficiently developed? Notice where some good scene opportunities are being brushed over. These are places where you probably SUMMARIZED or used EXPOSITION rather than developed the moment with sensory detail. 11. Are the scenes well-modulated? You want to alternate action, reflection, dialogue, and exposition—not action scene followed by action scene followed by action scene. If there's no modulation, the high points just run together with the low points and the story will feel monotonous. 12. Is the point of view modulated? You want "distant shots" as well as detailed "close-ups." 13. Is there real engagement with language? Or, oops, is the prose style pretty much a soggy paper towel? 14. Look out for dull, hackneyed language; cliché words and expressions: a. b. c. d. e. f. g. h. "sly smile" "evil smirk" "deep into his eyes" "heart leaped to his throat" "face etched with concern" "blacker than night" "bitter tears" majestic sunset," etc. 15. Try some interesting figurative language! Look at Lorrie Moore and Annie Proulx for evocative, surprising, moving, vivid, juicy metaphors and similes. 16. Watch out for monotonous sentence length and style; no rhythmic, modulated, or otherwise engaging sentences. 17. Listen for voice—does your narrator, whether she's wholly omniscient, limited omniscient, or first-person—have a distinctive way of talking? * Scene = an unbroken stretch of time and action, usually in one place. Unlike a summary or exposition, which may overview a broad period of time, a scene generally covers a brief, detailed, circumscribed period. Scenes are almost like small stories in themselves. Remember, there’s no need ever for writer’s block. llllllllllllll Commercial Screenwriting (in case you’re interested) Movies vs. Plays vs. Novels Novel: author has control of nearly all of the main product Plays: playwright has total control of script Movies: screenwriter usually has little control of anything Novel: can get directly into characters’ thoughts and also provide exposition easily Movies: primarily visual Plays: primarily verbal (dialogue) Novels: a solitary art Plays and especially movies: highly collaborative arts Basics BASICS Shooting BASICS or Production Script: Formatted for actual use on set. And there’s the: Pitch Outline Spec or Writer’s Script: Treatment Synopsis For shopping your script around. 100-120 pages. Period. In MANY commercial films, CONCEPT is key. A successful concept: Can be understood by an 8th grader Can be summed up in one or two sentences Is provocative Provides a compelling mental picture Has a main character who experiences a conflict which leads to an initial HOOK Has sequel potential Has “legs” (could work even without big stars) Will nonetheless attract a big star Stands out Is original but also has familiar elements (Being John Malkovich) You can see the whole movie in it Has broad appeal Is marketable; the exec knows immediately that the idea has potential Formulating the concept (the “one-line” or “logline”): Pose as question: What if Dorothy had a sister? What if Titanic were a spaceship instead of a boat? What if one of the ghostbusters were himself a ghost? Pose as a logline: TV Guide or newspaper movie section one-sentence summary Pose as a hook: The Graduate: Part II Out of Africa meets Pretty Lady Braveheart comes to America (The Patriot) Night of the Living Dead meets Star Wars (The Imposter) Night of the Living Dead meets Outbreak (The Invasion) Animal House meets The Good Girl (The Tao of Steve) Logline should have an implied structure—on hearing the concept, an exec would sense a beginning, middle, and end, or the “beats”: 1. Opening Image Every handbook you consult will 2. Theme Statement break these parts down a little 3. Set-up differently or with different headers 4. Catalyst 5. Debate 6. B Story (usually the love story, page 30) 7. Fun and Games 8. Midpoint 9. Bad Guys Close In 10.All is Lost 11.Dark Night of the Soul 12.Finale 13.Final Image The killer TITLE + the CONCEPT = a one-two Know Your Genres Thriller Love Story Action/Adventure Sci-Fi Horror Detective mystery Comedy …including ones not mentioned in your local video store: The Fish Out of Water Dances with Wolves, Dangerous Minds, Miss Congeniality, Legally Blonde, Benjamin Button, The Reader The Pet Who Heals Winn-Dixie, Seabiscuit, As Good as It Gets (sub-theme), Marley and Me The Buddy Story (Sensitive Male Bonding Flick) Ill-Fated Lovers (Casablanca, Romeo and Juliet, Plain Jane Transformed The Devil Wears Prada, Pretty Lady, My Fair Lady, Cinderella (of course)… Beloved Mentor Dead Poets Society, Dangerous Minds, Good Will Hunting Rites of Passage (A Few Good Men, Rocky, Titanic, The Reader) The Quest (Titanic, Troy, Indiana Jones, My Best Friend’s Wedding Monster in the House (The Exorcist, Tremors, Panic Room, Alien) The Brilliant Dope (Forrest Gump, Dave, I Am Sam) There is much, much, much, much, much, much, much, much, much, much, much, much, much more to this discipline. I’ve given you a wee taste, a feel for the commercial foundations. Finding resources is EASY To read actual film scripts, try out: www.isriptdb.com (Internet Movie Script Database) www.dailyscript.com www.newmarketpress.com/category.asp?id=10www.scriptcrawler.com (New Market Press’s film and television scripts for sale) www.script-o-rama.com www.simplyscripts.com TV and movie script writing site: www.cybercollege.com/index.htm Quicky on film script format: www.cybercollege.com/dram_flm.htm Longer thingy on script writing format: http://www.screenwriting.info/ These sites haven’t been thoroughly examined; they are suggested starting places only. BTW, how do you know when a website is junk? No contact info or verifiable background No affiliations, stated or linked Claims made without supporting evidence The site is problematically “.com” or other “.orgs” are getting easier to fudge, apparently No documentation of sources No documentation of little-known or debatable info Conspicuous ill-will, bias, disregard for opposing views Unedited and unproofread Links take you to advertisements or porn Comes from Wikipedia :) Wickedpedia There’s a whole world of non-formula filmmaking and screenwriting out there; you just might have to look a little further than franchise theaters or screaming TV trailers. E.g., visit the Fargo Theater! But, man, do you really want to write formula stuff?